China Society

The Trending Controversy Behind an Extraordinary Mount Everest Rescue

Chinese social media played a significant role in shaping the outcome of this incredible Mount Everest story.

Published

1 year agoon

The extraordinary nighttime rescue of a female Chinese mountain climber at the treacherous altitude of 8000 meters on Mount Everest was already a notable news story in its own right. However, when it was revealed that the woman declined to assume the full US$10,000 rescue fee, the story quickly spread across Chinese social media platforms, sparking fervent discussions on courage and (in)gratitude.

Recently, the news of two Chinese mountain climbers giving up on their dream to reach the summit of Mount Everest in order to rescue a female climber in distress has garnered widespread attention.

What initially seemed like a heartwarming tale of heroism quickly sparked intense debate when the 50-year-old Chinese woman refused to fully compensate her rescuers.

This incident has ignited discussions among netizens, covering financial concerns, moral responsibilities, and the notion that no good deed goes unpunished.

Sacrificing a Costly Dream

On May 18th in Nepal, at an altitude of 7,950 meters, four members of the Hunan Mountaineering Team (湖南登山队) embarked on their journey from the C4 camp on the southern slope of Mount Everest with the goal of reaching the summit.

At approximately 20:30, team leader Fan Jiangtao (范江涛) spotted a Chinese female climber huddled on the roadside at an altitude of 8,450 meters. The woman’s clothes were severely torn, one hand was exposed and blackened, and her face was coated with a thin layer of ice.

The woman seemingly undertook her climb without the aid of a Sherpa, who are typically experienced mountain guides and partners of climbers, belonging to the Nepalese ethnic group. They provide guidance and support to climbers during their ascent to different camps and, ultimately, the summit.

At an altitude of 8,000 meters on Mount Everest lies the treacherous “death zone,” where rescuing others can endanger the lives of the rescuers.

Despite initially intending to proceed with their ascent, Fan made the courageous decision to rescue the woman anyway. Along the way, he encountered another team member, Xie Ruxiang (谢如祥).

Luckily, Xie’s Sherpa guide was strong, and in order to convince the guide, Xie promised a reward of $10,000 if the Sherpa could safely bring the survivor back to the camp. Through the collective efforts of multiple individuals, including the determined Sherpa, they successfully brought Ms. Liu, who was in grave danger, back to the C4 camp.

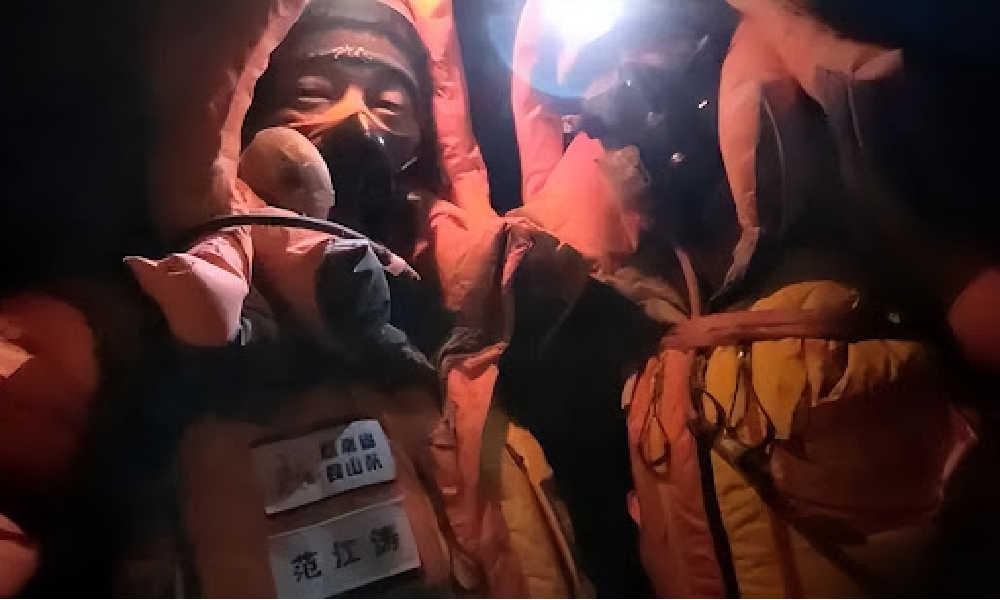

A photo of the mountain climbers rescuing Ms. Liu, source: Beijing Evening News.

Consequently, the two rescuers had to relinquish their long-held dream to reach the summit of the Mount Everest during this significant year, which marks the 70th anniversary of the first human ascent. Not only was reaching the summit at this particular time of great importance to the mountain climbers, they also spent approximately 400,000 yuan (around US$57,000) in preparation and training fees.

Mountain of Wealth?

As the Mount Everest rescue story gained attention on Chinese social media after Hunan media outlets reported it, news emerged on June 3rd that the rescued woman allegedly intended to contribute only part of the rescue fee owed to the Sherpa who had aided in her rescue.

This information was later confirmed by one of the rescuers, Fan Jiangtao. Fan revealed that the woman had given a tip of merely $1,500 to the Sherpas, while other members of the team gave $1,800. Additionally, she expressed willingness to pay only $4,000 of the total $10,000 rescue fee.

“This angered me, and I informed her that if she maintained this attitude, I did not want any of that money, and she need not give it to me,” stated Fan. Consequently, Fan and the other rescuer, Xie, ended up paying the $10,000 fee themselves.

Fan Jiangtao (left) and Xie Ruxiang (right) after rescuing Liu, source: Beijing Evening News

As the hashtag “Woman Rescued on Everest Does not Want to Pay the Full Rescue Fee” (#珠峰被救女子不愿支付全部救援费用#) received over 370 million views on Weibo, the story ignited a fierce online debate.

While some netizens argued against criticizing Ms. Liu without knowing the full context of her personal financial circumstances, many others condemned her, stating that financial constraints should not serve as an excuse for individuals engaging in such mountain climbing endeavors, especially on Mount Everest.

Several Weibo users discussed how climbing Mount Everest would require a minimum budget of at least 500,000 yuan (approximately US$70,000) to cover expenses such as climbing permits, gear, guides, flights, not to mention the necessary training and preparation time.

Considering the widely acknowledged high costs associated with climbing Mount Everest, including rescue fees, many contend that Ms. Liu’s refusal extends beyond a mere financial issue. Additionally, most commenters suggest that Liu should not impose the burden of her rescue expenses on the rescuers.

One Weibo user expressed, “[If I were her], even if it meant going bankrupt, I would still borrow money to cover the training and preparation fees of those two rescuers [due to their failed summit attempt], let alone $10,000!”

The Farmer and the Snake

After the media exposed Ms. Liu’s refusal to pay the full amount, the two rescuers made an appeal to netizens, urging them not to engage in online harassment towards the rescued woman. They emphasized: “Rescuing people is our duty, and whether or not she expresses gratitude is her own choice. These are two completely separate matters.”

However, many argued that their critical remarks about Liu were not to be equated with ‘online harassment,’ asserting that individuals should face consequences for their actions.

Some Chinese social media users also suggested that individuals displaying ingratitude like this are unworthy of being rescued. They drew parallels to the well-known Chinese fable of “the farmer and the snake” (农夫与蛇, nóngfū yǔ shé), where a compassionate farmer saves a freezing snake during a cold winter, only to be bitten and killed by it later on. People argue that no good deed goes unpunished and also use the idiom “it’s hard to be a good person” (好人难做, hǎo rén nán zuò).

The farmer and the snake, image via Sohu.com

Liu was also labeled as a “white-eyed wolf” (白眼狼, bái yǎn láng), a term used to describe someone particularly heartless and cruel. One Weibo user commented, “We should collectively raise money to send her back to the mountain.”

Concerns were also raised that this incident might have implications for future rescues involving climbers in distress, as it could make other climbers more hesitant to come to the aid of those in need.

Various state media outlets, including Nanfang Daily (南方日报) and Hongxing News (红星新闻), urged the woman to take responsibility and acknowledge the heroic actions of the rescuers. By emphasizing the importance of not discouraging selfless acts like this, the story continued to generate online discussions, with netizens actively putting more pressure on the case.

More to the Story

On June 10, there was a somewhat unexpected follow-up to the story. As reported by NBD.com and other Chinese media outlets, Ms. Liu traveled to Changsha on June 7th to personally meet her rescuers and thank them for what they did for her.

In an in-depth article titled “They Gave up Reaching the Mount Everest Summit to Save Someone: Why Did the Rescued Person ‘Not Thank Them’ and ‘Not Pay Her Rescuers’?” (“他们放弃登顶珠峰救人:被救者为何“不感谢”“不付救援费?”), the Chinese magazine Sanlian Lifeweek (三联生活周刊) shared additional details about the entire incident, addressing some lingering questions.

According to the article, Ms. Liu arrived in Kathmandu on May 6th this year. Just 13 days later, she was found in a perilous situation, struggling for her life during her Mt Everest summit. This short time frame between her arrival and summit is highly unusual, as the usual preparation, climbing, and acclimatization period takes around 40 days.

Ms. Liu had registered with the Chengdu-based Kaitu Mountaineering company (成都凯途高山户外运动有限责任公司) to climb Mount Everest and paid them 400,000 yuan (US$56,110) for the expedition. The woman had allegedly spent all her savings to fulfill her dream of climbing Mount Everest.

As an experienced cross-country runner, the 50-year-old woman was in good physical condition and had undergone prior training for the expedition. Interestingly, she was also part of the same mountaineering team as her rescuers Fan and Xie.

Before commencing her journey, Ms. Liu discussed her climbing plans with the team leader of the company. Despite informing them that she needed to complete the summit and descent within just 20 days because her employer at a state-owned company would not allow a longer abscence, she was assured it was feasible. Normally, an Everest expedition takes about two months.

Although Ms. Liu embarked on the mountain separately from the other team members from Hunan, she had a Sherpa accompanying her. However, due to unfortunate circumstances and miscommunication, she found herself stranded and exhausted at an altitude of approximately 8000 meters, with limited oxygen, before being discovered by Fan Jiangtao at 20:30 on May 18th.

The difficult rescue of Liu took place after dark, image via Sohu.com.

Liu’s Sherpa had apparently signalled the need to return to the C4 camp for boiled water, and Liu couldn’t communicate her physical exhaustion and desire for him to stay. She then found that she was unable to detach herself from the rope due to the locking mechanism of the carabiner getting stuck, rendering her immobile.

Fan and later Xie never expected to find their team member on the mountain, assuming she had withdrawn from the expedition long ago upon learning that her job wouldn’t allow her to be away for 40 days. Without Fan and Xie, Liu’s life would have been lost on the mountain.

The Sanlian Lifeweek article doesn’t feature an interview with Liu herself but emphasizes that she is not a wealthy person and works an office job. It also highlights her introverted nature, which might have contributed to the perception of her being ungrateful.

During her visit to Changsha on June 7th, Liu finally had dinner with Fan Jiangtao, Xie Ruxiang, and several other team members to address mixed emotions and misunderstandings after her rescue. Allegedly, she also brought US$10,000 and an additional 20,000 yuan ($2800) to give to Fan and Xie, although they declined the offer.

Meanwhile, the Chengdu-based Kaitu Mountaineering company has now stepped forward and declared their commitment to bearing the financial burden of Liu’s rescue. They acknowledge the role they played, along with their Sherpa, in contributing to Liu’s predicament.

In a statement released on June 10, the company expressed gratitude towards the rescue team and announced that they had reached an agreement with the rescuers, the Sherpa rescue team, and Ms. Liu regarding the coverage of expenses (#珠峰被救女子所雇登山公司发文#).

Despite understanding the complete story, many netizens still express their inability to comprehend why Liu didn’t come forward earlier to cover the entire amount.

Others also think that being an introverted person has nothing to do with not being able to properly express gratitude for someone saving your life.

And then there are also those who are happy with the current outcome and the role played by social media in pressuring the responsible parties to provide financial compensation: “Without the internet, this never would have happened.”

By Zilan Qian and Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

Also Read

China Memes & Viral

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

This week, Chinese netizens discussed subway seat confrontations, a shocking public stabbing, and Hu Youping’s heroism. Also: more trending topics, from hallucinogenic mushrooms to traveling pandas and reactions to the Biden vs. Trump debate.

Published

3 weeks agoon

July 7, 2024

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #32

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Get up, stand up

◼︎ 2. What’s New and Noteworthy – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s Remarkable – Seeing little people

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – Wild Child: missing in action

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Bystander effect

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – “City bu City”

Dear Reader,

Over the past few weeks, there has been a lot of discussion on Chinese social media about young people refusing to give up their seats for older people on the subway, sometimes leading to explosive situations.

On June 16, security was called when a young man on a Shenyang subway crumbled after an old man demanded that he’d give up his seat for him. In a video of the incident, which soon went viral, the young man can be heard screaming: “Are you giving me money? No? Then don’t bother me! I’m just happy to be sitting here. What’s wrong with me grabbing a seat?

Another subway incident went trending a week later. On June 24, a 65-year-old man started harassing a young woman on Beijing Subway Line 10 after she refused to give up his seat to him. The man became aggressive, started slapping the woman and put his cane in between her legs, trying to force her to stand up. The incident, which was filmed by other passengers, caused outrage on social media and the man was later detained by Beijing police.

A day later, in Wuhan, an elderly man and a young woman also got into an altercation that was caught on camera. After female passenger took the only available seat during morning rush hour on Line 2, the man reminded her that she should give up her seat out of respect for the elderly. “Why should I?” she asked: “I don’t owe you anything. I work overtime until 12:00 at night every day, and now you expect me to give up my seat during the morning rush hour?”

These incidents have sparked discussions about how people feel about these situations. In China, where respect for the elderly is deeply ingrained in the culture, should you give up your seat to the elderly on public transport because it is your duty, or is it just a personal choice? In an online poll held by Sina News, over 93% of respondents said they felt it was not their duty to give up their seat but a personal choice—a matter of courtesy.

“As long as you’re not sitting in a priority seat, you don’t have to give up your seat,” a top comment said. “It’s not easy being working class.” Many people echoed this sentiment, siding with the younger people who are facing their own tough struggles in China today. “I’d advise the elderly not to crowd public transport during the morning and evening rush hour,” another popular comment said, receiving thousands of likes.

These discussions signal a social shift: “When the topic comes up about young people not giving up their seats for the elderly, have you ever considered that these young people have been working all day? If you feel so strongly about it being your duty, how about you call a taxi for the elderly yourself?”

While many commenters expressed that people are not obliged to give up their seats to others, some, including pregnant women, complained about the overall reluctance of other passengers to give up their seats for them. “It feels like everybody is tired,” one Weibo user wrote.

Standing By

Another noteworthy discussion on Chinese social media recently was not about sitting down but about standing by. In a stabbing incident caught on camera by bystanders, a man locally known as “Bag-Clutching Brother” (夹包哥) was killed in the city of Songyuan in China’s Jilin province on June 30. His real name was Mr. Zhao, but he earned the nickname “Jiabaoge” (夹包哥, “Brother Clutch Bag”) for his eccentric square dancing while clutching a bag.

A video of the horrific incident shows Mr. Zhao happily dancing in a public square in Songyuan, with dozens of people present, when a man suddenly draws a knife and starts stabbing him. As the crowd watches on, the attack continues. Moments later, Mr. Zhao can be seen lying in a puddle of blood while still being attacked. Bystanders did not intervene. The attacker, a local drunk who did not even know “Brother Clutch Bag,” was detained by police. Zhao died of his injuries.

The incident caused a shock wave on social media. “They all stand in a circle and watch,” a typical comment said. “Not one of them stepped forward to help.” Some people called the onlookers “cold and detached” (“冷漠围观”).

While many suggest the onlookers are selfish and too preoccupied with filming to actually intervene, others suggested they were just scared to face the consequences of intervening.

There is a complex interplay of factors associated with the likelihood of people intervening when witnessing a crime or other emergency. Research points out that the higher the levels of fear among bystanders, the less likely they are to intervene. The more they perceive themselves as strong, the more likely they are to help. Additionally, the more people witnessing an emergency, the less personal responsibility is felt, reducing the chances of intervention.

As a victim, you might be more fortunate if just one person sees your predicament—and comes to your aid—than if a hundred people look on and do nothing.

Hu Youping

This issue perhaps also played a role in a third noteworthy topic that became a major trend recently, which I also wanted to mention here. It concerns the death and honoring of Ms Hu Youping (胡友平). Hu Youping, a 54-year-old school bus attendant, stepped in to help when a Japanese mother and child were attacked by a man with a knife at a school bus stop in Suzhou on June 24.

Hu was working that day when, around 4 pm, someone wielding a knife started attacking people at the bus stop near Xindi Center on Tayuan Road. As she rushed forward to stop the attacker, she was stabbed multiple times—one of the stabs hit her heart. On June 26, two days after the incident, Hu succumbed to her injuries.

The story of Hu Youping is remarkable on many levels. Not only was she brave, but she also intervened during a time when multiple stabbing incidents were making the news (also see: Jilin stabbings). Her courage became the focus of Chinese media reports about the Suzhou stabbing, diverting attention from the suspect’s motivations and discussions questioning China’s public safety. Adding to the story is that Hu protected a Japanese mother and child, which, in the context of Sino-Japanese tensions, reinforced her selflessness.

Hu’s face was suddenly everywhere. Netizens praised her kindness, and state media honored her bravery. As she officially received the title of “Model of Righteousness,” she was exemplified as embodying the kindness and courage of the Chinese people by local authorities. The Tianjin Radio and Television Tower even lit up in honor of Hu Youping, projecting her portrait on the side of the building.

Hu Youping is seen as a selfless heroine. Her story is not just propagated by official channels, it also resonates with the people. “People like Ms. Hu Youping and other heroes are remarkable, not only for their willingness to sacrifice themselves but also for inspiring those around them,” one Weibo blogger wrote.

Perhaps Hu Youping is the role model people need at this time, when so many stories about a lack of altruism, conflicting values, and moral crises are trending on social media. She was not necessarily an extraordinary person; she was a normal, kind-hearted and hard-working woman who would not stand by while seeing people in trouble.

However, while Hu Youping’s bravery is inspiring, her courage also serves as a cautionary tale. In one thread about the passive crowds watching Mr. Zhao get killed, commenters wrote: “Look what happened to Ms. Hu Youping. She got killed while bravely intervening, so who would dare to step in here?”

Her courage and ensuing death have ignited a realistic debate on what helping others may look like when confronting an armed attacker directly is not an option: “If someone is attacking with a knife and you are unarmed, your only option is to run. If you can help others to run with you, you are already a hero.”

In the end, Hu Youping triggers discussions on kindness, fearlessness, and doing what’s right. At a time when the social moral compass seems adrift, people like Hu help recalibrate it. Whether it means standing up or sitting down, stepping in or getting out, it’s always best to follow that personal moral compass regardless of what others do. Sometimes, that might mean sitting down when you need to rest, knowing that taking care of yourself is just as important. At other times, it means standing up when nobody else does, and rising not because it’s your duty, but because you know it’s the right thing to do.

Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang have helped compile some of the topics mentioned in this week’s newsletter. As always, please do not hesitate to reach out if you’d like to share something you’ve spotted or share your ideas with me.

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

What’s New

Humble Prodigy or Deceptive Impostor? | It’s rare for a math competition to become the focus of nationwide attention in China. But since 17-year-old vocational school student Jiang Ping made it to the top 12 among contestants from prestigious universities worldwide, her humble background and outstanding achievement sparked debates and triggered rumors.

“Scared to Intervene” | In a shocking incident caught on camera, a well-known Songyuan resident nicknamed “Brother Clutch Bag” was tragically stabbed to death. On Weibo, people have reacted with disbelief.

Another One Bites the Dust | Li Shangfu allegedly “took advantage of his position to seek benefits for others” and received large sums of money.

What’s Trending

JUNE 26

🇺🇸 Biden vs Trump | Just like in the rest of the world, Biden and Trump’s presidential debate became a hot topic on Chinese social media. Chinese America watchers harshly criticized the debate, describing it as a race between a “madman and a senile patient.” Others perceived the overall energy and quality of the debate as indicative of troubled times for America and see the presidential campaign as a sign of Western democracy falling behind. Many commenters suggest that it does not really matter for China who becomes president, as both candidates are expected to adopt a tough stance on China. Nonetheless, there were various posts indicating a preference for Trump because he generates more memes and jokes on Chinese social media and is “more fun to watch.”

JUNE 29

🐼 From Sichuan to San Diego | They are the first set of pandas to make their way to the U.S. in 21 years: Yun Chuan (云川) and Xin Bao (鑫宝) safely arrived in San Diego on June 28 after a long flight from China. Their caretakers in Sichuan had to say goodbye to them for a loan period of at least ten years. On Chinese social media, many commenters expressed sadness about the pandas leaving China, wondering if their American adventure is really in their best interest.”

JUNE 30

🚀 Accidental Rocket | Was it a plane? Was it a meteor? Videos of an explosion in the hills near Gongyi City in Henan recently went viral (link). The huge impact was not caused by a meteor; it was a rocket. While performing a ground test, the Chinese rocket by space startup Space Pioneer (天兵科技) was accidentally launched and crashed near a residential area. There were no reports of casualties. A few days later, Space Pioneer sincerely apologized and promised that the company would compensate anyone who suffered property damage due to the test failure. The incident has sparked questions on why a private enterprise was able to test out rockets in Gongyi in the first place.

JULY 1

🏸 Zhang Zhijie Dies | On June 30, the young Chinese badminton player Zhang Zhijie (张志杰) collapsed and convulsed during a game in Indonesia. Videos of the incident (link) showed how it took about 40 seconds before medics arrived to attend to him. After being rushed to the hospital, the 17-year-old player from Jiaxing, Zhejiang, passed away. According to Indonesia’s badminton association, Zhang died due to sudden cardiac arrest. On Weibo, a hashtag about Zhang’s death garnered over 560 million views (#张志杰去世#) since late June. Zhang’s sister shared her grief and shock about her brother’s death on her Weibo account. Zhang’s mother was so overcome with grief that she had to be temporarily hospitalized earlier this week. Zhang’s family is now in Indonesia, seeking more clarity on his death and holding those responsible accountable.

JULY 2

🚗 Molly and Mr. Musk | “Hello Mr. Musk, I’m Molly from China. I have a question about your car. When I draw a picture, sometimes it will disappear like this. You see it? So can you fix it? Thank you.” Recently, a 7-year-old girl from Beijing named Molly recorded a video for Elon Musk, in which she complained in English about a bug in Tesla’s sketchpad: when adding a new stroke to her drawing, Molly found that previous strokes would sometimes disappear. In response, Musk replied to her on the X platform, “Sure.” The little exchange generated a lot of attention for Molly on Chinese social media, where the little girl was applauded for how she managed to address an issue with her drawing pad directly with Mr. Musk himself.

JULY 6

🌊 Dongting Floods | A dike of Dongting Lake in Yueyang, Hunan Province, burst on Friday afternoon, causing serious flooding in the area. What started as a 10-meter-wide breach eventually became a breach of approximately 225 meters (738 feet) wide. This flooding of China’s second-largest freshwater lake has already affected approximately 5,000 people, and around 3,000 people were relocated on Saturday. Efforts to seal the breach in the embankment in Huarong County are underway, with over 4700 people actively helping to control the flood.

JULY 7

📈 Peak in Death Rates | On Sunday, reports of China facing an imminent peak in death rates went trending on Weibo, where a related hashtag became one of the most-searched topics (#中国将迎来人口死亡高峰#). Chinese news outlet Jiemian News reported on a new study published in the latest issue of the Chinese magazine “Population Research” (人口研究), where researchers predict an unprecedented peak in death rates due to various factors, including China’s rapidly aging population, historical birth fluctuations, and increased longevity. As the aging population from the post-war mid-20th-century birth boom leads to a rapid rise in deaths, researchers emphasize the need to prepare for the societal impacts of this peak, including improved palliative care and better planning for funeral services. “Can we first fix the problem of post-graduate unemployment?” one top commenter wondered.

What’s Noteworthy

Do you remember when US Treasury Secretary Yellen had some supposed ‘magic mushrooms’ in Beijing? The mushroom dish she had at a local restaurant is called “jiànshǒuqīng” (见手青) in Chinese; it’s the Lanmaoa asiatica mushroom species that grows in China’s Yunnan region and is considered hallucinogenic if not prepared properly, causing visions that locals call “xiǎorénrén” (小人人), literally meaning seeing “tiny people.” The Chinese is similar to the English term “Lilliputian hallucinations” that refers to visual hallucinations which could also include seeing tiny humans.

The fact that Yellen had this dish actually made it more popular online in China, leading more people to order the mushrooms through online channels.

This week, one Chinese girl named Xiaolin who had ordered 500 grams of the mushrooms became a top trending topic online. She used them for her mushroom soup and added them to her noodles. She consumed all of the mushrooms within one day. Later that night, Xiaolin started feeling unwell. She started seeing numerous “tiny people” running around her house, and when the little figures tried to whisper in her ear and get into her bed, the terrified girl rushed to her friend’s house, who decided to take her to the hospital due to her incoherent speech and strange behavior. The girl was eventually hospitalized due to wild mushroom poisoning.

The story garnered 160 million views on Weibo (#女子吃1斤见手青后看见一屋人#), where many people are now more aware of the dangers of consuming wild mushrooms if not properly cooked. However, there are also many others who are only more curious now; they also want to see ‘little people’ walking around their house.

Meme comparing Vision Pro to the ‘magic’ jianshouqing mushroom: which surreal experience is better?

Some memes relating to this topic suggest that having “jiànshǒuqīng” is a cheaper and more interactive VR experience than getting the Apple Vision Pro. It surely isn’t something that authorities would like to see more people experiment with: a vlogger who tried out some raw mushrooms on her livestream was immediately shut down this week.

What’s Popular

The highly anticipated Chinese film Wild Child (野孩子) was scheduled for a nationwide premiere on July 10. Earlier this year, Wild Child won the Weibo award for the most-anticipated movie of the year. Starring the immensely popular former TFBoys leader Wang Junkai (also known as Karry Wang 王俊凯, 1999), the film had generated significant excitement among Chinese movie-goers. However, this week, the film distributor abruptly announced the cancellation of its release, citing alleged post-production delays. The cancellation, which quickly trended and sparked widespread discussion on Chinese social media, was particularly surprising as tickets were already being sold in the presale box office.

Directed by Yin Ruoxin (殷若昕), Wild Child is based on a true story about two boys from a poor background who struggle to get by. The film addresses the theme of “children living in difficulty” (困境儿童), depicting the lives of children growing up in poverty. The two boys, one a thief and the other an orphan, are united by fate and bond as brothers as they face their challenges together.

Why was the movie canceled so close to its premiere date? Was the withdrawal a purely commercial decision driven by poor presale figures, as suggested in a recent column by People’s Daily, or were there political motivations involved? Could its theme be misaligned with the upcoming Party’s third plenary session? Or is the portrayal of children facing social difficulties simply too sensitive? While the true reasons remain unclear, many fans are hopeful they will still have the opportunity to see the film.

What’s Memorable

For this pick from the archive, and in the context of recent discussions on bystanders not intervening, we revisit a 2015 article about a young Chinese student who helped an elderly lady who had fallen on the street, only to be held liable for her injuries. Stories like these are often cited to explain why people hesitate to help someone in need.

Weibo Word of the Week

“City or not” | Our Weibo phrase of the week is City bu City a (City不City啊), translated as “City or not?”, a phrase that has recently taken the Chinese internet by storm.

The phrase first became popular thanks to American influencer Paul Mike Ashton, nicknamed “Bao Bao Xiong” (保保熊, Baby Bear), who runs a Chinese-language account on Douyin. On his channel, Ashton shares humorous snippets about his life in China, where he works as an entertainer and tour guide.

In one video from April this year, Ashton posted a clip in which he cycles through the city like a Shanghai ‘city girl’ who often mixes Chinese and English words, calling himself “very city” (“我是好city”). He says: “I’m so city, a city girl. It’s so cool, breezy. Life in the city is so good, I feel so free.”

Ashton later began incorporating this phrase more frequently in his videos, often involving his sister, who also speaks Chinese in these humorous exchanges. Walking on the Shanghai Bund, the brother and sister describe Shanghai as “so city” (“好city啊”). While walking on the Great Wall, Bao Bao asks his sister if it’s “city or not” (it’s not).

In other videos in which the two are traveling through China, Ashton repeatedly asks his younger sister if certain things are “city or not,” to which she usually responds humorously: “It’s very city.”

In this context, “city” has evolved from a noun into a quirky adjective, describing something that embodies the essence of urban life; something that is ‘city’ is metropolitan, lively, and modern. It’s very tongue-in-cheek and also serves as a playful commentary on how young Chinese people often mix Chinese and English words to sound more sophisticated and trendy.

This phenomenon sparked the ‘city or not’ meme, which even reached the Foreign Ministry this week when spokesperson Mao Ning was asked about it. She responded that she had heard about the new use of the phrase and that it is a positive sign of foreigners enjoying life in China.

Chinese authorities and state media have also jumped on this trend to promote tourism. By now, the meme has been imitated and adapted by various local tourism departments. Ashton himself has encouraged foreigners to come and experience Chinese culture (and its very ‘city’ city life), further boosting its popularity.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

China Society

Hero or Zero? China’s Controversial Math Genius Jiang Ping

Humble prodigy or deceptive impostor? Jiang Ping has been fueling online discussions since her remarkable score in the Alibaba maths competition.

Published

3 weeks agoon

July 5, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

It’s rare for a math competition to become the focus of nationwide attention in China. But since 17-year-old vocational school student Jiang Ping made it to the top 12 among contestants from prestigious universities worldwide, her humble background and outstanding achievement sparked debates and triggered rumors.

About a month ago, nobody had ever heard of Jiang Ping (姜萍). But that all changed in June 2024, when the Alibaba Global Mathematics Competition announced its finalists. Organized by Alibaba’s DAMO Academy in collaboration with the China Association for Science and Technology and the Alibaba Foundation, this competition is open to math enthusiasts worldwide.

This year, among the finalists from top universities around the globe, the 17-year-old Jiang Ping from Jiangsu province stood out. Scoring 93 points and ranking 12th globally, she was not just the only girl in the top 30 but she was also not even a math major—Jiang studies fashion design at a local vocational school. Her remarkable score, combined with her humble background, thrust her into the center of an unexpected public debate.

‘Good Will Hunting’

When the Alibaba Math Competition finalist list was announced in June, Jiang Ping became an instant internet sensation. Her story seemed straight out of an inspiring movie: a poor family, a modest educational background, and exceptional intelligence.

According to her parents and teachers, Jiang Ping had excelled at math since middle school, far surpassing her peers. However, her talent was limited to mathematics, and her weakness in other subjects meant she could only attend a vocational school, and she enrolled at Lianshui Secondary Vocational School, a path often seen as a dead end in China’s competitive educational landscape.

Fate intervened when her math teacher, Wang Runqiu (王闰秋), a master’s graduate from Jiangsu University who never qualified for a PhD program, noticed her extraordinary talent during a monthly math exam. Wang, who also participated in Alibaba’s competition and ranked over 100th, provided Jiang with advanced math textbooks. He believed her potential should not go to waste.

Determined, Jiang Ping self-studied mathematics alongside her fashion design curriculum, even using an English-Chinese dictionary to understand partial differential equations textbooks in English. When Jiang heard that Alibaba’s competition had no educational requirements, she seized the opportunity, and her talent finally came to light.

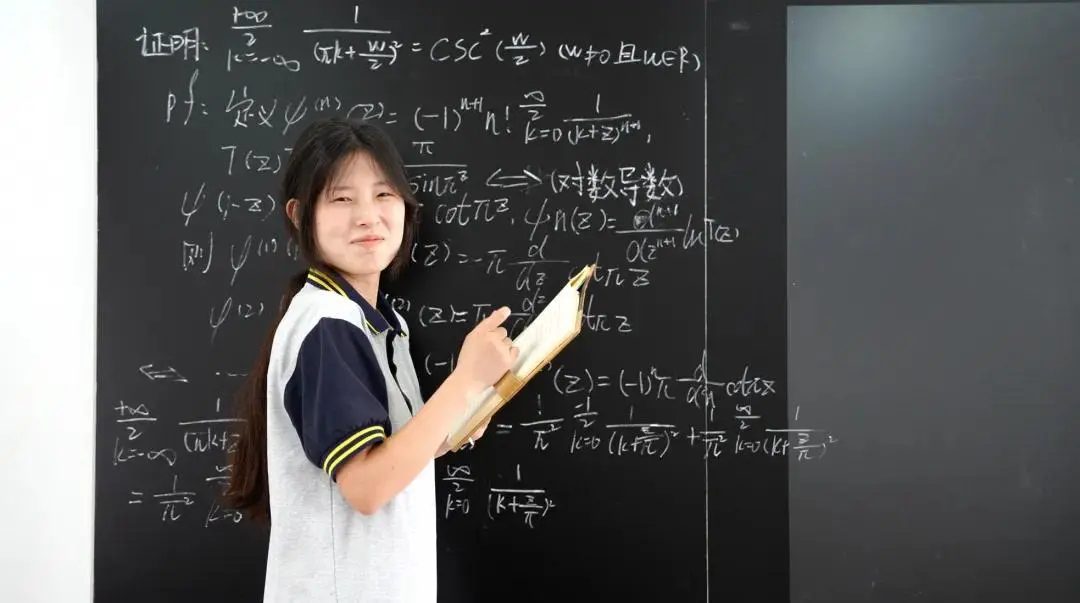

Jiang Ping, image via iFeng News.

The public initially seemed to love the story of a small-town Chinese girl experiencing a miraculous turning point in her life. Her 70-year-old father could hardly earn more than a few hundred yuan a month, and she often worked during holidays to help support her family.

According to Xinjing News, by March 2024, her family had applied for a subsistence allowance but had yet to receive it. After Jiang Ping’s story went viral, the allowance was immediately secured. Her village and school became new hotspots for influencers. Vloggers flocked to her home to film TikTok videos, and even tourists from other provinces visited Lianshui County just to take photos at Jiang’s school.

Wang Runqiu, Jiang Ping’s teacher

Everything seemed to be going well. Education blogger Luo Miao (@罗淼_吐槽用) posted that Jiang Ping and her teacher Wang Runqiu had achieved something more miraculous than the story portrayed in the American movie “Good Will Hunting,” which is also about a self-taught mathematical genius. However, the real world is not a movie. This celebration took a downturn in less than five days.

A Questionable Math Problem

Shortly after the finalists were announced and Jiang Ping’s name spread across social media, online discussions questioning her mathematical abilities began to emerge on forums like Zhihu. The focal point of these discussions was a scene from an official Alibaba video where Jiang Ping is seen holding scratch paper and solving a math problem on a blackboard.

On June 18, a WeChat post by renowned math competition coach Zhao Bin (赵斌) was trending on Weibo. Zhao, who had participated in the Alibaba competition three times and made it to the finals each time, asserted that Jiang Ping’s advancement to the finals was 99.99% likely fabricated. He raised doubts about Jiang Ping’s solution process on the blackboard, pointing out issues like “the domain of definition was incorrect” and “the differentiation symbol is written in the wrong place.” He concluded that Jiang was not familiar with these math questions and may have simply copied the answers from her scratch paper.

Zhao Bin further suggested that this might be orchestrated by Jiang Ping’s teacher Wang Runqiu, who probably wanted to hype up Jiang Ping’s image as an unrecognized genius and his own image as a mentor. Zhao also stated that if he was wrong, Jiang Ping truly was a math prodigy and that if she would make it to university, he would personally finance her tuition fees.

On June 19, 39 contestants from the Alibaba competition released a petition to the organizing committee. Besides the problems addressed by Zhao, they mentioned another point of contention: a teacher who had seen Jiang Ping’s exam paper commented that she exhibited “proficient use of LaTeX” while answering questions. LaTeX, a typesetting system for scientific documents, is highly sensitive to writing errors, which contradicts the frequent errors in Jiang Ping’s handwriting in the video.

This was also mentioned by Peking University professor Yuan Xinyi (袁新意) in a lengthy analysis on Zhihu, where he argued that as a vocational school student, Jiang Ping couldn’t possibly be proficient in using LaTeX. In their petition, the 39 contestants put forth specific demands, including the public release of Jiang Ping’s answer sheets for review by all finalists and a request for an independent third-party investigation.

Of course, there are those who choose to believe in Jiang Ping. Science fiction writer Bei Xing (@北星微博) made meticulous notes and explanations of Jiang Ping’s problem-solving process on the blackboard. He concluded that it was impossible to have such a clear approach if she had just copied someone else’s answers, as Zhao assumed. It was also understandable for a 17-year-old who had almost entirely self-taught herself to make some writing errors and formatting irregularities.

Up until this point, most discussions were still about academic integrity. But the fact that Alibaba and Damo Academy did not directly address these doubts only triggered more rumors. Many influencers with large followings, despite lacking a math background, also started to chime in with comments like “Jiang Ping doesn’t even recognize mathematical symbols,” leading to another surge of speculation and defamation directed at Jiang Ping.

Online Chaos

On June 23rd, the Weibo user ‘Oxford Kate Zhu Zhu’ (@牛津Kate朱朱), a mathematics PhD candidate at Oxford University, posted on Weibo that she had faced significant online abuse after expressing support for Jiang Ping. She said that she has sought legal assistance to deal with the online attacks. This post, which quickly went viral, showed how the controversy surrounding Jiang Ping has gone beyond mathematics or academic integrity.

By June 20th, Jiang Ping herself had already been doxxed. Someone posted her personal information online, including photos of her ID card. This practice is referred to as “opening the box” (开盒) on the Chinese internet. Netizens on platforms like Zhihu and Hupu began spreading rumors about Jiang Ping and her relationship with her mathematics teacher, with so-called “informants” even coming forward to allegedly confirm their “improper relationship.” Subsequently, a screenshot of Jiang Ping’s previous math exam score, showing she had scored only 83 points, was also leaked.

Professor of Criminal Law at Tsinghua University Lao Dongyan (@劳东燕2004) expressed concern about this situation, posting on Weibo to remind netizens that while people have the right to question Jiang Ping’s remarkable results, they should not throw around baseless accusations and push the debate in a direction that borders on defamation.

However, many people continue to see Jiang Ping’s amicable relationship with her teacher and her former 83-point exam score as justification to spread her private photos, transcripts, and even monthly exam papers on the Internet.

By now, the situation has become so messy that the Education Bureau of Lianshui County had to step in and set the record sraight on some trivial matters, such as the authenticity of Jiang’s monthly exam score and whether some teacher had bought her snacks or not.

Wang Hongqin vs Jiang Ping

Amidst the chaos, voices of reason remain: some netizens have expressed disappointment at Alibaba’s continued silence. They suggest that regardless of how Jiang Ping made it to the math competition finals, as an underage girl, she should not be thrust into the eye of the hurricane.

Meanwhile, another story has drawn parallels to Jiang’s situation. Recently, some netizens discovered that the son of the famous Chinese actress Wang Yan (王艳), Wang Hongqin (王泓钦), was admitted to Peking University as a “high-level athlete” based on his basketball talent. However, there are publicly available records indicating that his athletic achievements were not that impressive at all.

Wang Hongqin and Jiang Ping

This raised many discussions on Chinese social media. Netizens questioned why Jiang Ping, with her outstanding math achievements, wasn’t celebrated in the same way as Wang Hongqin. Others highlighted the disparity in opportunities for talented student from different backgrounds.

There were also questions about why Jiang Ping was receiving so much online hate, while Wang Hongqin did not. Under a Weibo post discussing Wang Yan’s son’s admission to Peking University, one comment explained public reasoning: “Wang Yan has access to high-level resources that are out of reach for ordinary people. In contrast, Jiang Ping is seen differently. When someone tries to break through societal layers [like that], they are dragged out and “paraded” through the streets.”

The discussions on the different public reactions to Wang Hongqin and Jiang Ping relate to a time of social insecurity when people face a competitive education system and a worsening job market. In this context, they are less likely to relate to “zero to hero” stories.

When someone with a low educational background achieves success, they are now often seen as cheaters rather than being celebrated. While people often feel powerless to challenge the privileges of the elite, the sudden rise of a vocational school student like Jiang Ping intensifies feelings of deprivation and being bypassed. Even though Jiang might have reached the finals through her own mathematical talent, there is still a lot of resentment towards the 17-year-old rural girl, who lacks background and connections. This misplaced anger is a reflection of deeper societal issues and inequalities.

Despite being at the center of the battlefield of public opinions, Jiang Ping has not made any statement yet. On June 22nd, she participated in Alibaba’s math competition finals, and perhaps now—as in every summer before—she is preparing to find a part-time job to support her family. The outcome of the finals will be announced in August, so Jiang Ping’s story will undoubtedly be continued.

By Ruixin Zhang

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?