China Insight

“What The F*ck is Communism?” – Discussion on Communism Takes over Weibo

A discussion on communism has taken over Weibo, as opinion leader Ren Zhiqian publicly stated that communist slogans have deceived Chinese people for over 10 years. His post instantly became trending: “What the f*ck is Communism anyway?”

Published

9 years agoon

After reports of an overall declining faith in communism, the Communist Youth League reiterated their strong believe in communism on Weibo, under the slogan: “We are the successors of Communism”. Chinese opinion leader Ren Zhiqian publicly critiqued their stance. His post instantly became trending, igniting a hot online debate on communism.

On the 21st of September, the Communist Youth League (共青团) posted a China Youth Daily article about “faith” on their official Weibo account, claiming that communism is at the heart of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Chinese nation at large. The article was written by famous Marxist scholar Wang Xiangming (王向明).

The Communist Youth League is the youth movement of the People’s Republic of China, run by the CPC.

“Let us hold up the flag of communism, because we are the successors of communism.”

“For us, communism is our highest ideal, and we are on the road to achieve it,” they write on their official Weibo page. “At the present stage, we are realizing the great rise of the Chinese people, and are building on modernizing the powerful and civilized socialism. Let us hold up the flag of communism, boldly and confidently, because: we are the successors of communism.”

With their Weibo post, the Communist Youth League use the hashtag #We Are The Successors of Communism (#我们是共产主义接班人#), referring to a 1961 theme song that has been used by the League since 1978.

Mainland China’s popular real estate entrepreneur and opinion leader Ren Zhiqian (任志强, nearly 34 million Weibo fans) publicly responded to the article with his own post titled: “Are We the Successors of Communism?” [Edit March 5, 2016: This post is no longer accessible since Ren’s Weibo account has been removed, but you can find a screenshot of his post here.]

In the post, he critiques the Communist Youth League’s article, saying: “We’ve been deceived by these communist slogans for years!” Ren’s post has been viewed over a million times, and has received messages of sympathy from thousands of Weibo users, instantly becoming the top trending Weibo message of the day.

“Communism, what the fuck is communism?”

A user called “Chinese Moviemaker” responds: “Red Guards, oh Little Red Guards, the young people of China have been fooled!!”

An employee of a Henan real estate company bluntly stated: “Communism, what the fuck is communism?”, while others stated that “Communism is the biggest catastrophe in human history”.

In his article, Ren Zhiqian explains his experience with communism in the past, and shares his views for it in the future.

“I am responding to the ‘We are the Successors of Communism’ Weibo post,” he writes: “We have been hearing our elder brothers and sisters singing this “We are the Successors of Communism” song since childhood, and we grew up with it.”

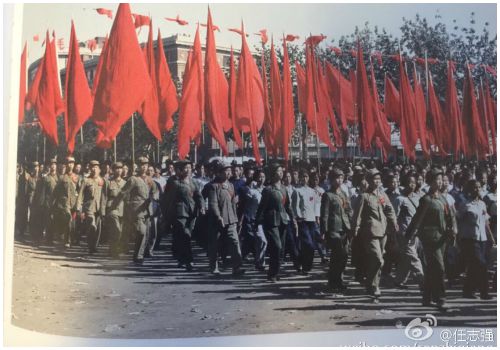

“When I was in the third grade, wearing a red neckscarf, I also learned this song. Every time we saw the five-starred red flag raised, we saluted it with our right hand, and sang this song. Our hearts were full of confidence and hope!”

“We dreamed of being seen by Leader Mao Zedong: a real successor of communism”

“When I went to Middle School in 1964, the first thing we did every day was practice marching,” Ren writes: “For the National Day parade, celebrating the fifteenth anniversary of the founding of the New China, I became a proud member of the Young Pioneers of China, as the young drummer. We dreamed of being seen by Leader Mao Zedong, a real successor of communism.”

“We lined up by the East Chang’an Avenue Beijing Hotel on the 1st of October, a bit over 5 AM, anxiously waiting for the National Day salute to go off. It was a moment of dreams coming true. On the sound of the drum, we walked to Tiananmen Square. Because I was a short kid at the time, I was the first in the row, and I felt proud that I would be nearer to Mao Zedong at Tiananmen’s City Gate than the others. My parents were also there, I wanted to see them, and I hoped they would see me.”

He continues:

“But when the moment came, I was so nervous, that when we passed the eastern marble pillars, and the sound of the drums and cheers came up, I could only look down at the white line underneath my feet. I was afraid that it would affect the entire formation if I did not walk straight. I did not look up at all, not even at the Tiananmen City Gate. I just saw it from the corner of my eyes. When we finally reached the western pillars, and I stopped the drums, and it was already too late to look back.”

“Once I returned to school, I regretted not seeing Mao Zedong and I secretly cried. But I felt very proud to be successor of communism.”

But then Ren’s happy memories of communism change as the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) begins, and his parents are accused of being capitalists.

“I never thought that when the Cultural Revolution began a few months later, my parents would become ‘capitalist-roaders’, and I would be the child of criminals, and get the glorious title of a ‘son of a bitch’. My dream to grow up to be a next generation communist changed to being a child who had to be rehabilitated.

“We have been deceived for years.”

“We’ve been deceived for years. The Cultural Revolution only let me know the class struggle under a proletarian dictatorship. And that there is no next generation of communism.”

Ren writes how him and his parents turned from city people into farmers during their rehabilitation. Despite the hardships, people still had trust in the nation:

“We were more determined to join the Communist Party of China, and had confidence in rescuing people in need. We remained convinced that the great leader Chairman Mao was correct. All the problems in China were caused by those people hidden in the Party who were on Khrushchev’s side, and were doing bad things.”

“The invincible Mao Zedong thought has let thousands of people starve to death.”

“But when Deng Xiaoping resigned, weeks after the Tiananmen events, the society started thinking. It was not until the overthrow of the “Gang of Four”, and the Third Plenum of the CPC and the ‘70% right 30% wrong’, that we got to know more errors from the once Great Leader.”

Ren tells how China changed after the death of Mao:

“Rightists who were overthrown were politically rehabilitated. The People’s Communes were dissolved. Farmer’s land was redistributed. The errors caused by the Cultural Revolution were corrected. The ‘Four Olds’, that were first knocked to the ground, were put back on their feet, and we again had a comeback of tradition (..) The capitalist class, that were first overthrown by the revolution, now became an important force in China’s economic development.”

“The invincible Mao Zedong Thought has let thousands of people starve to death, and we don’t even know who many people died through persecution during the Cultural Revolution. Maybe even more people died because of wrong political policies than because of the war.”

“The Communist Youth League who now wants to welcome communism – are you joking?”

“But China’s reform and opening has completely freed people of any food and clothing problems. The Reforms and Opening of China has re-established the confidence and trust in the Chinese leadership and the Communist Party. It also let the world know China. Everyone hopes the Communist Party of China will realise its promises of democracy, freedom, equality, and the rule of law, and lead the Chinese people to prosperity. They hope even more that they achieve the great ideal of communism. I also hope that communism can be realized. But what is the path to achieve it?”

“History has taught us that a violent revolution does not work. It has also taught us that public ownership does not work. That planned economy does not work. And that the absence of democracy and rule of law does not work!”

“Deng told us that China is still in the primary stage of socialism. It make take several generations to go to an intermediate stage. And it might take who-knows-how-many generations before we reach the higher goal. Deng Xiaoping also told us that it might take many generations before the wealth of some people turn into common wealth. If there is no step-by-step expansion of the middle class, it is impossible to achieve common prosperity.”

“However, the impatient Chinese people cannot wait for generations without results , and want to achieve the goal of common prosperity.(..) It took 1000 years to go from feudal to capitalist society. It has not even been four decades since China’s primary stage of socialism. The Communist Youth League who now wants to welcome communism – are you joking? The only way to possibly ever achieve the ideal of communism is a long, long road, taking the effort of dozens of generations.”

“Without democracy and freedom, how can we achieve equality under the law?”

Ren concludes his article by emphasizing the need for democracy: “Without democracy and freedom, how can we achieve equality under the law?”, he writes.

“Perhaps there are many theoretical and institutional issues that gradually need to be reformed and resolved. Perhaps we need to understand that achieving communism is a very far-reaching and hard goal. But most of all, there needs to be a clear understanding that reaching communism is not just a very far-reached and ambitious goal, but that it will not be realised by this generation, or the ones after.”

“We can have ambitious goals, but it is more important that we live in reality. We first need to solve the system’s immediate problems. First, Chinese people should be confident in a system that allows people to share democracy and freedom. First, stable incomes need to be achieved. First, we need laws that can really protect people’s lives and property. First, the Chinese people need to join the system of values shared by the world. Otherwise, how could communism be ever reached?”

Ren’s article has caused much commotion on Weibo. While some criticise communism and the system in general, others call for more a more nuanced discussion on the future of communism in China.

User Luo Qiang says: “After reading Ren Zhiqiang’s brilliant text, I am overwhelmed with emotions. I can’t help but also want to ridicule the system.” Weibo netizen Qinghua Sun Liping says:

“It’s good to say that communism is our ideal. It is better to have some ideals than to have none at all. (..) But to achieve communism, we need to concretise our targets.”

Ren’s article has got over 1 million views, was shared on Weibo over 13,780 times, received 8850 comments, and got over 15,000 ‘likes’.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Insight

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

The story of ‘Fat Cat’ has become a hot topic in China, sparking widespread sympathy and discussions online.

Published

3 months agoon

May 9, 2024

The tragic story behind the recent suicide of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ has become a major topic of discussion on Chinese social media, touching upon broader societal issues from unfair gender dynamics to businesses taking advantage of grieving internet users.

The story of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer from Hunan who committed suicide has gone completely viral on Weibo and beyond this week, generating many discussions.

In late April of this year, the young man nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ (胖猫 Pàng Māo, literally fat or chubby cat), tragically ended his life by jumping into the river near the Chongqing Yangtze River Bridge (重庆长江大桥) following a breakup with his girlfriend. By now, the incident has come to be known as the “Fat Cat Jumping Into the River Incident” (胖猫跳江事件).

News of his suicide soon made its rounds on the internet, and some bloggers started looking into what was behind the story. The man’s sister also spoke out through online channels, and numerous chat records between the young man and his girlfriend emerged online.

One aspect of his story that gained traction in early May is the revelation that the man had invested all his resources into the relationship. Allegedly, he made significant financial sacrifices, giving his girlfriend over 510,000 RMB (approximately 71,000 USD) throughout their relationship, in a time frame of two years.

When his girlfriend ended the relationship, despite all of his efforts, he was devastated and took his own life.

The story was picked up by various Chinese media outlets, and prominent social and political commentator Hu Xijin also wrote a post about Fat Cat, stating the sad story had made him tear up.

As the news spread, it sparked a multitude of hashtags on Weibo, with thousands of netizens pouring out their thoughts and emotions in response to the story.

Playing Games for Love

The main part of this story that is triggering online discussions is how ‘Fat Cat,’ a young man who possessed virtually nothing, managed to provide his girlfriend, who was six years older, with such a significant amount of money – and why he was willing to sacrifice so much in order to do so.

The young man reportedly was able to make money by playing video games, specifically by being a so-called ‘booster’ by playing with others and helping them get to a higher level in multiplayer online battle games.

According to his sister, he started working as a ‘professional’ video gamer as a means of generating money to satisfy his girlfriend, who allegedly always demanded more.

He registered a total of 36 accounts to receive orders to play online games, making 20 yuan per game (about $2.80). Because this consumed all of his time, he barely went out anymore and his social life was dead.

In order to save more money, he tried to keep his own expenses as low as possible, and would only get takeout food for himself for no more than 10 yuan ($1,4). His online avatar was an image of a cat saying “I don’t want to eat vegetables, I want to eat McDonald’s.”

The woman in question who he made so many sacrifices for is named Tan Zhu (谭竹), and she soon became the topic of public scrutiny. In one screenshot of a chat conversation between Tan and her boyfriend that leaked online, she claimed she needed money for various things. The two had agreed to get married later in this year.

Despite of this, she still broke up with him, driving him to jump off the bridge after transferring his remaining 66,000 RMB (9135 USD) to Tan Zhu.

As the story fermented online, Tan Zhu also shared her side of the story. She claimed that she had met ‘Fat Cat’ over two years ago through online gaming and had started a long distance relationship with him. They had actually only met up twice before he moved to Chongqing. She emphasized that financial gain was never a motivating factor in their relationship.

Tan additionally asserted that she had previously repaid 130,000 RMB (18,000 USD) to him and that they had reached a settlement agreement shortly before his tragic death.

Ordering Take-Out to Mourn Fat Cat

– “I hope you rest in peace.”

– “Little fat cat, I hope you’ll be less foolish in your next life.”

– “In your next life, love yourself first.”

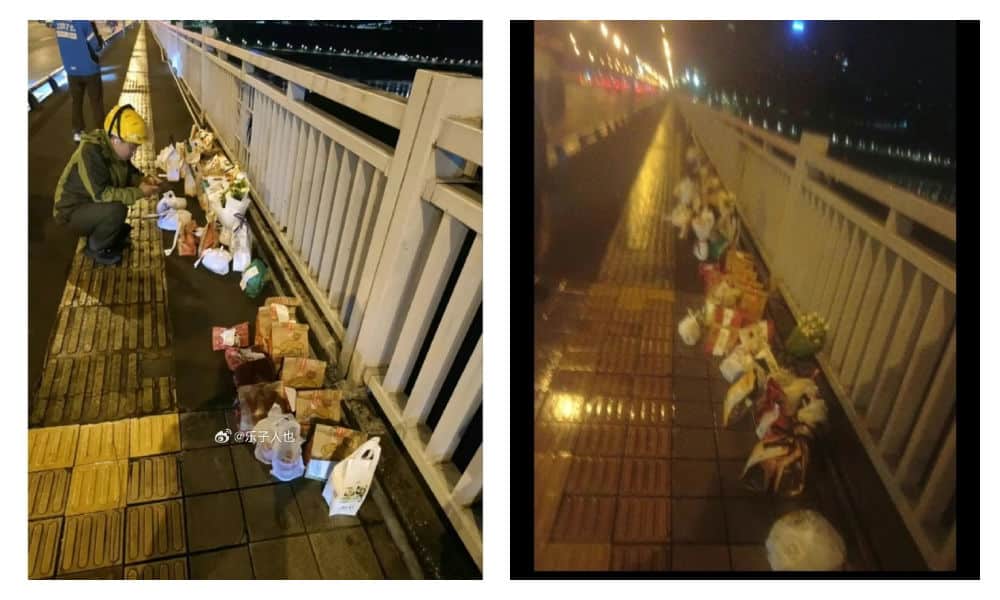

These are just a few of the messages left by netizens on notes attached to takeout food deliveries near the Chongqing Yangtze River Bridge.

AI-generated image spread on Chinese social media in connection to the event.

As Fat Cat’s story stirred up significant online discussion, with many expressing sympathy for the young man who rarely indulged in spending on food and drinks, some internet users took the step of ordering McDonalds and other food delivery services to the bridge, where he tragically jumped from, in his honor.

This soon snowballed into more people ordering food and drinks to the bridge, resulting in a constant flow of delivery staff and a pile-up of take-out bags.

Delivery food on the bridge, photo via Weibo.

However, as the food delivery efforts picked up pace, it came to light that some of the deliveries ordered and paid for were either empty or contained something different; certain restaurants, aware of the collective effort to honor the young man, deliberately left the food boxes empty or substituted sodas or tea with tap water.

At least five restaurants were caught not delivering the actual orders. Chinese bubble tea shop ChaPanda was exposed for substituting water for milk tea in their cups. On May 3rd, ChaPanda responded that they had fired the responsible employee.

Another store, the Zhu Xiaoxiao Luosifen (朱小小螺蛳粉), responded on that they had temporarily closed the shop in question to deal with the issue. Chinese fast food chain NewYobo (牛约堡) also acknowledged that at least twenty orders they received were incomplete.

Fast food company Wallace (华莱士) responded to the controversy by stating they had dismissed the employees involved. Mixue Ice Cream & Tea (蜜雪冰城) issued an apology and temporarily closed one of their stores implicated in delivering empty orders.

In the midst of all the controversy, Fat Cat’s sister asked internet users to refrain from ordering take-out food as a means of mourning and honoring her brother.

Nevertheless, take-out food and flowers continued to accumulate near the bridge, prompting local authorities to think of ways of how to deal with this unique method of honoring the deceased gamer.

Gamer Boy Meets Girl

On Chinese social media, this story has also become a topic of debate in the context of gender dynamics and social inequality.

There are some male bloggers who are angry with Tan Zhu, suggesting her behaviour is an example of everything that’s supposedly “wrong” with Chinese women in this day and age.

Others place blame on Fat Cat for believing that he could buy love and maintain a relationship through financial means. This irked some feminist bloggers, who see it as a chauvinistic attitude towards women.

A main, recurring idea in these discussions is that young Chinese men such as Fat Cat, who are at the low end of the social ladder, are actually particularly vulnerable in a fiercely competitive society. Here, a gender imbalance and surplus of unmarried men make it easier for women to potentially exploit those desperate for companionship.

The story of Fat Cat brings back memories of ‘Mo Cha Official,’ a not-so-famous blogger who gained posthumous fame in 2021 when details of his unhappy life surfaced online.

Likewise, the tragic tale of WePhone founder Su Xiangmao (苏享茂) resurfaces. In 2017, the 37-year-old IT entrepreneur from Beijing took his own life, leaving behind a note alleging blackmail by his 29-year-old ex-wife, who demanded 10 million RMB (±1.5 million USD) (read story).

Another aspect of this viral story that is mentioned by netizens is how it gained so much attention during the Chinese May holidays, coinciding with the tragic news of the southern China highway collapse in Guangdong. That major incident resulted in the deaths of at least 48 people, and triggered questions over road safety and flawed construction designs. Some speculate that the prominence given to the Fat Cat story on trending topic lists may have been a deliberate attempt to divert attention away from this incident.

‘Fat Cat’ was cremated. His family stated their intention to take necessary legal steps to recover the money from his former girlfriend, but Tan Zhu reportedly already reached an agreement with the father and settled the case. Nevertheless, the case continues to generate discussions online, with some people wondering: “Is it over yet? Can we talk about something different now?”

Fat Cat images projected in Times Square

However, given that images of the ‘Fat Cat’ avatar have even appeared in Times Square in New York by now (Chinese internet users projected it on one of the big LED screens), it’s likely that this story will be remembered and talked about for some time to come.

UPDATE MAY 25

On May 20, local authorities issued a lengthy report to clarify the timeline of events and details surrounding the death of “Fat Cat,” which had attracted significant attention across China.

The report concluded that there was no fraud involved and that “Fat Cat” and his girlfriend were in a genuine relationship. Tan did not deceive “Fat Cat” for money; the transfers were voluntary. Furthermore, Tan returned most of the money to his parents.

The gamer’s sister is reportedly still being investigated for potentially infringing on Tan’s privacy by disclosing numerous private details to the public.

In the end, one thing is clear in this gamer’s tragic story, which is that there are no winners.

By Manya Koetse

– With contributions by Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy.

Published

3 months agoon

May 3, 2024

It seemed like such a good idea. For this year’s World Book Day, Chinese tea brand LELECHA (乐乐茶) put a spotlight on Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881-1936), one of the most celebrated Chinese authors the 20th century and turned him into the the ‘brand ambassador’ of their special new “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙) milk tea.

LELECHA is a Chinese chain specializing in new-style tea beverages, including bubble tea and fruit tea. It debuted in Shanghai in 2016, and since then, it has expanded rapidly, opening dozens of new stores not only in Shanghai but also in other major cities across China.

Starting on April 23, not only did the LELECHA ‘Smoky Oolong” paper cups feature Lu Xun’s portrait, but also other promotional materials by LELECHA, such as menus and paper bags, accompanied by the slogan: “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” (“老烟腔,新青年”). The marketing campaign was a joint collaboration between LELECHA and publishing house Yilin Press.

Lu Xun featured on LELECHA products, image via Netease.

The slogan “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” is a play on the Chinese magazine ‘New Youth’ or ‘La Jeunesse’ (新青年), the influential literary magazine in which Lu’s famous short story, “Diary of a Madman,” was published in 1918.

The design of the tea featuring Lu Xun’s image, its colors, and painting style also pay homage to the era in which Lu Xun rose to prominence.

Lu Xun (pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a leading figure within China’s May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1915-24) is also referred to as the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance. It was the cultural revolution brought about by the political demonstrations on the fourth of May 1919 when citizens and students in Beijing paraded the streets to protest decisions made at the post-World War I Versailles Conference and called for the destruction of traditional culture[1].

In this historical context, Lu Xun emerged as a significant cultural figure, renowned for his critical and enlightened perspectives on Chinese society.

To this day, Lu Xun remains a highly respected figure. In the post-Mao era, some critics felt that Lu Xun was actually revered a bit too much, and called for efforts to ‘demystify’ him. In 1979, for example, writer Mao Dun called for a halt to the movement to turn Lu Xun into “a god-like figure”[2].

Perhaps LELECHA’s marketing team figured they could not go wrong by creating a milk tea product around China’s beloved Lu Xun. But for various reasons, the marketing campaign backfired, landing LELECHA in hot water. The topic went trending on Chinese social media, where many criticized the tea company.

Commodification of ‘Marxist’ Lu Xun

The first issue with LELECHA’s Lu Xun campaign is a legal one. It seems the tea chain used Lu Xun’s portrait without permission. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s great-grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation, quickly demanded an end to the unauthorized use of Lu Xun’s image on tea cups and other merchandise. He even hired a law firm to take legal action against the campaign.

Others noted that the image of Lu Xun that was used by LELECHA resembled a famous painting of Lu Xun by Yang Zhiguang (杨之光), potentially also infringing on Yang’s copyright.

But there are more reasons why people online are upset about the Lu Xun x LELECHA marketing campaign. One is how the use of the word “smoky” is seen as disrespectful towards Lu Xun. Lu Xun was known for his heavy smoking, which ultimately contributed to his early death.

It’s also ironic that Lu Xun, widely seen as a Marxist, is being used as a ‘brand ambassador’ for a commercial tea brand. This exploits Lu Xun’s image for profit, turning his legacy into a commodity with the ‘smoky oolong’ tea and related merchandise.

“Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you in an article. ”

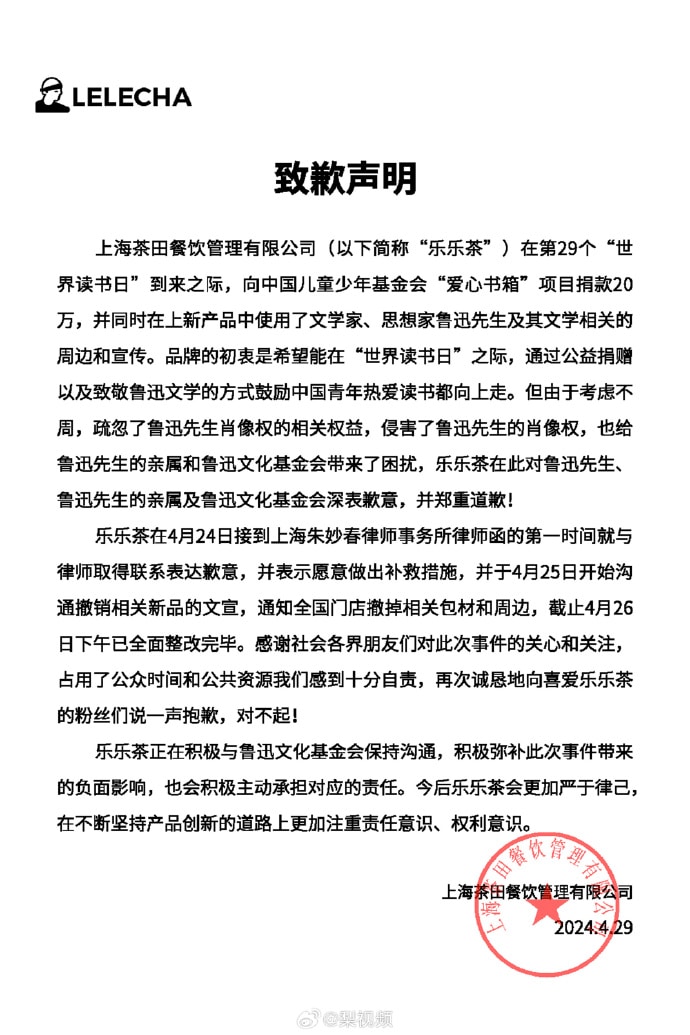

On April 29, LELECHA finally issued an apology to Lu Xun’s relatives and the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation for neglecting the legal aspects of their marketing campaign. They claimed it was meant to promote reading among China’s youth. All Lu Xun materials have now been removed from LELECHA’s stores.

Statement by LELECHA.

On Chinese social media, where the hot tea became a hot potato, opinions on the issue are divided. While many netizens think it is unacceptable to infringe on Lu Xun’s portrait rights like that, there are others who appreciate the merchandise.

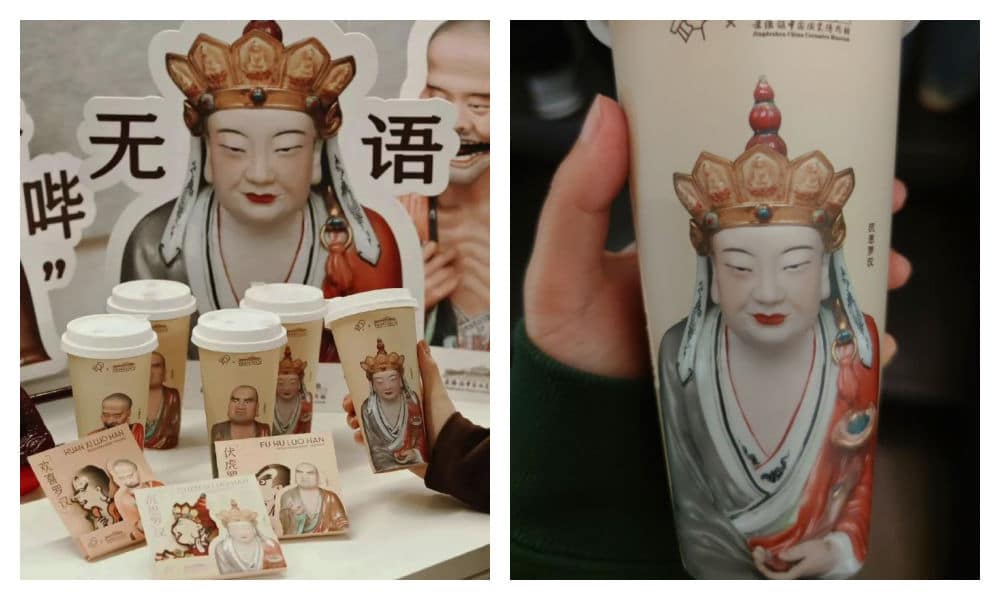

The LELECHA controversy is similar to another issue that went trending in late 2023, when the well-known Chinese tea chain HeyTea (喜茶) collaborated with the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum to release a special ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ (佛喜) latte tea series adorned with Buddha images on the cups, along with other merchandise such as stickers and magnets. The series featured three customized “Buddha’s Happiness” cups modeled on the “Speechless Bodhisattva” (无语菩萨), which soon became popular among netizens.

The HeyTea Buddha latte series, including merchandise, was pulled from shelves just three days after its launch.

However, the ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ success came to an abrupt halt when the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Shenzhen intervened, citing regulations that prohibit commercial promotion of religion. HeyTea wasted no time challenging the objections made by the Bureau and promptly removed the tea series and all related merchandise from its stores, just three days after its initial launch.

Following the Happy Buddha and Lu Xun milk tea controversies, Chinese tea brands are bound to be more careful in the future when it comes to their collaborative marketing campaigns and whether or not they’re crossing any boundaries.

Some people couldn’t care less if they don’t launch another campaign at all. One Weibo user wrote: “Every day there’s a new collaboration here, another one there, but I’d just prefer a simple cup of tea.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Schoppa, Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia UP, 159.

[2]Zhong, Xueping. 2010. “Who Is Afraid Of Lu Xun? The Politics Of ‘Debates About Lu Xun’ (鲁迅论争lu Xun Lun Zheng) And The Question Of His Legacy In Post-Revolution China.” In Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China, 257–284, 262.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?