China and Covid19

“Why Is It Always the BBC That Has Problems?” – Chinese Response to Arrest of Foreign Reporter

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs blamed the BBC for distorting facts and painting China in a bad light.

Published

2 years agoon

Chinese media reports about the official response to the arrest of a UK reporter during protests in Shanghai has gone viral on Chinese social media, without explicitly mentioning the circumstances in which the incident occurred. Chinese netizens are now demanding videos to ‘expose’ how the situation unfolded.

News about the arrest of BBC journalist Edward Lawrence while covering the second night of protests in Shanghai on November 27 has not only made headlines in English-language media, it also became a trending topic on Chinese social media.

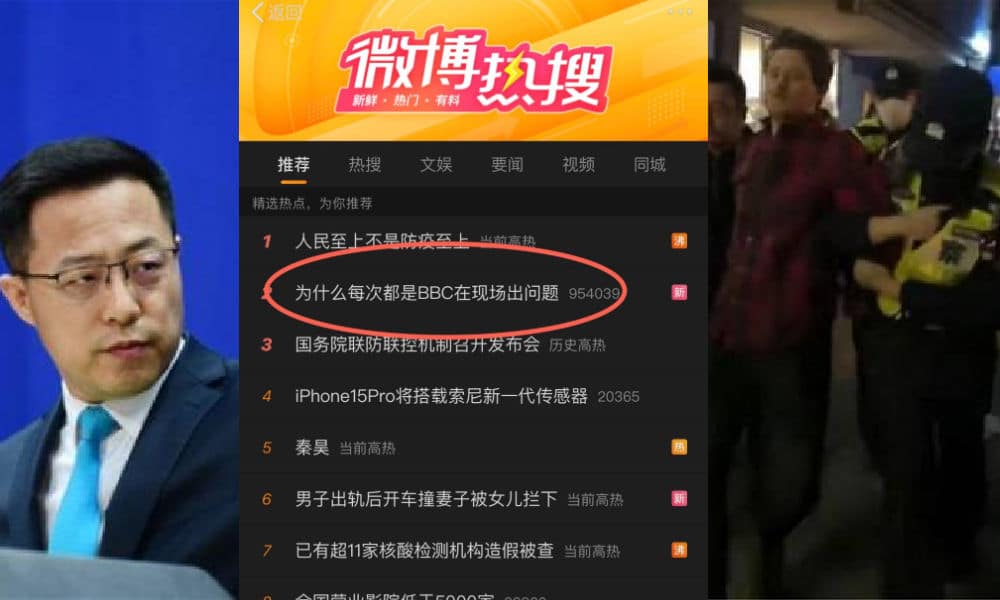

On Tuesday, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Zhao Lijian (赵立坚) responded to the incident in a regular press conference. A day earlier, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak denounced the arrest of the BBC journalist as “shocking and unacceptable.”

BBC Statement on Ed Lawrence pic.twitter.com/wedDetCtpF

— BBC News Press Team (@BBCNewsPR) November 27, 2022

But according to Zhao, the incident has been distorted by Western media to paint China in a bad light. The Chinese side claims that Lawrence refused to cooperate with the police and failed to show his credentials. “There are many foreign media in China, why is it always the BBC that has problems at the scene? This is a question that must be seriously considered.”

Zhao’s comments went viral on Weibo in two hashtags, namely “Zhao Lijian Presents the Truth about the BBC Reporter Who Was Taken Away” (#赵立坚介绍BBC记者被带离真相#), and “Why Is It Always BBC That Has Problems at the Scene?”(#为什么每次都是BBC在现场出问题#).

Zhao Lijian on Tuesday.

A translation of the full statement by Zhao was also posted on the official website of the Chinese Embassy in the UK. Part of the statement said:

“On the night of November 27, to maintain public order, local police in Shanghai asked people who had gathered at a crossroads to leave. One of those at the scene is a resident journalist from the BBC. Though the police made it clear to the journalist and others that they needed to leave, the journalist refused to go and in the entire time did not identify himself as a journalist. The police then took him away from the scene. After verifying his identity and informing him of pertinent laws and regulations, the police let him leave. Everything was conducted within legal procedures. This BBC journalist refused to cooperate with the police’s law enforcement efforts and then acted as if he were a victim. The BBC immediately twisted the story and massively propagated the narrative that its journalist had been “arrested” and “beaten” by police while he was working, simply to try to paint China as the guilty party. This deliberate distortion of truth is all too familiar as part of the BBC’s distasteful playbook.”

On Weibo, the statement by Zhao, including video, was published by state media outlet Global Times (环球时报), which did not explicitly report that the incident happened during demonstrations in Shanghai. Instead, they reported about ‘the scene’ and that it allegedly happened “in the course of his work” “记者在工作中”).

One top comment on Weibo said: “The BBC is always making up rumors, there are engaged in an anti-Chinese campaign. They should be punished.” That comment received over 6700 likes.

“Are BBC reporters really reporting on the news, or are they making the news up?” another popular reply said.

The idea that Western mainstream media outlets are ‘creative’ in their reporting has been a long-standing one on Chinese social media. In a well-known example from 2017, social media users accused American broadcaster CNN of staging an anti-ISIS protest in London after a Twitter user uploaded a video that showed how police and TV producers directed a group of Muslim women to stand in line with their protest signs behind the TV anchor. The BBC was also widely criticized for using the allegedly “staged” CNN footage.

Although many netizens gave their thumbs up for Zhao’s remarks about the arrest of Lawrence, there were also some who wanted to know more about the incident.

One popular comment said: “Was there just one BBC reporter at the scene? Why would take away a hard-working journalist? What was the BBC reporter recording? Were there also Chinese reporters? If so, can you give us the real recordings of what was happening at the scene?”

“Domestic reporters wouldn’t dare to post it,” someone replied: “The scene was too electrifying.”

There were also those who made sarcastic comments relating to the ‘outside force’ narrative that became ubiquitous in China’s online media sphere in response to the (censored) protests that have been taking place across China.

“Give us the irrefutable evidence to expose these ‘outside forces,'” some said.

The idea that “outside forces” or “external forces” (外部势力) had something to do with the protests first started increasingly popping up in social media discussions on late Sunday night, and it was also raised in an online column by the political commentator Hu Xijin (read here).

Zhao Lijian also reiterated this idea in Monday’s press conference in by talking about “forces with ulterior motives” who had connected the Urumqi fire, which initially triggered the unrest, with the local response to Covid-19.

“Thousands of people are protesting, they must all be foreigners. CNN and BBC are fully responsible. Except for us and North Korea, the whole world is watching these news channels. The entire world – except for us – is wrong,” one commenter wrote.

Many commenters kept asking for video proof of the incident: “I demand you make the video public so we can all denounce them, we will resolutely denounce them” one person wrote, adding a melon-eating emoji (吃瓜 ‘eating melon’ is frequently used as a humorous reference to standing by and watching the scene unfold).

“We firmly denounce disturbing editing, give us the original video!”

Despite the banter, there were also some more serious comments. One Weibo user wrote: “Foreign reporters often do not have good intentions, they are often distorting the facts, and I hate that. But domestic reporters do not dare to face the epidemic situation and only report on the good news.”

“So who can actually give us the truth?” others wondered.

Read more about the “11.24” unrest or “white blank paper protests” in China here.

By Manya Koetse , with contributions by Miranda Barnes

If you appreciate what we do, please subscribe here or support us by donating.

Featured image via Zhejiang Daily.

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China and Covid19

Sick Kids, Worried Parents, Overcrowded Hospitals: China’s Peak Flu Season on the Way

“Besides Mycoplasma infections, cases include influenza, Covid-19, Norovirus, and Adenovirus. Heading straight to the hospital could mean entering a cesspool of viruses.”

Published

8 months agoon

November 22, 2023

In the early morning of November 21, parents are already queuing up at Xi’an Children’s Hospital with their sons and daughters. It’s not even the line for a doctor’s appointment, but rather for the removal of IV needles.

The scene was captured in a recent video, only one among many videos and images that have been making their rounds on Chinese social media these days (#凌晨的儿童医院拔针也要排队#).

One photo shows a bulletin board at a local hospital warning parents that over 700 patients are waiting in line, estimating a waiting time of more than 13 hours to see a doctor.

Another image shows children doing their homework while hooked up on an IV.

Recent discussions on Chinese social media platforms have highlighted a notable surge in flu cases. The ongoing flu season is particularly impacting children, with multiple viruses concurrently circulating and contributing to a high incidence of respiratory infections.

Among the prevalent respiratory infections affecting children are Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections, influenza, and Adenovirus infection.

The spike in flu cases has resulted in overcrowded children’s hospitals in Beijing and other Chinese cities. Parents sometimes have to wait in line for hours to get an appointment or pick up medication.

According to one reporter at Haibao News (海报新闻), there were so many patients at the Children’s Hospital of Capital Institute of Pediatrics (首都儿科研究所) on November 21st that the outpatient desk stopped accepting new patients by the afternoon. Meanwhile, 628 people were waiting in line to see a doctor at the emergency department.

Reflecting on the past few years, the current flu season marks China’s first ‘normal’ flu peak season since the outbreak of Covid-19 in late 2019 / early 2020 and the end of its stringent zero-Covid policies in December 2022. Compared to many other countries, wearing masks was also commonplace for much longer following the relaxation of Covid policies.

Hu Xijin, the well-known political commentator, noted on Weibo that this year’s flu season seems to be far worse than that of the years before. He also shared that his own granddaughter was suffering from a 40 degrees fever.

“We’re all running a fever in our home. But I didn’t dare to go to the hospital today, although I want my child to go to the hospital tomorrow. I heard waiting times are up to five hours now,” one Weibo user wrote.

“Half of the kids in my child’s class are sick now. The hospital is overflowing with people,” another person commented.

One mother described how her 7-year-old child had been running a fever for eight days already. Seeking medical attention on the first day, the initial diagnosis was a cold. As the fever persisted, daily visits to the hospital ensued, involving multiple hours for IV fluid administration.

While this account stems from a single Weibo post within a fever-advice community, it highlights a broader trend: many parents swiftly resort to hospital visits at the first signs of flu or fever. Several factors contribute to this, including a lack of General Practitioners in China, making hospitals the primary choice for medical consultations also in non-urgent cases.

There is also a strong belief in the efficacy of IV infusion therapy, whether fluid-based or containing medication, as the quickest path to recovery. Multiple factors contribute to the widespread and sometimes irrational use of IV infusions in China. Some clinics are profit-driven and see IV infusions as a way to make more money. Widespread expectations among Chinese patients that IV infusions will make them feel better also play a role, along with some physicians’ lacking knowledge of IV therapy or their uncertainty to distinguish bacterial from viral infections (read more here)

To prevent an overwhelming influx of patients to hospitals, Chinese state media, citing specialists, advise parents to seek medical attention at the hospital only for sick infants under three months old displaying clear signs of fever (with or without cough). For older children, it is recommended to consult a doctor if a high fever persists for 3 to 5 days or if there is a deterioration in respiratory symptoms. Children dealing with fever and (mild) respiratory symptoms can otherwise recover at home.

One Weibo blogger (@奶霸知道) warned parents that taking their child straight to the hospital on the first day of them getting sick could actually be a bad idea. They write:

“(..) pediatric departments are already packed with patients, and it’s not just Mycoplasma infections anymore. Cases include influenza, Covid-19, Norovirus, and Adenovirus. And then, of course, those with bad luck are cross-infected with multiple viruses at the same time, leading to endless cycles. Therefore, if your child experiences mild coughing or a slight fever, consider observing at home first. Heading straight to the hospital could mean entering a cesspool of viruses.”

The hashtag for “fever” saw over 350 million clicks on Weibo within one day on November 22.

Meanwhile, there are also other ongoing discussions on Weibo surrounding the current flu season. One topic revolves around whether children should continue doing their homework while receiving IV fluids in the hospital. Some hospitals have designated special desks and study areas for children.

Although some commenters commend the hospitals for being so considerate, others also remind the parents not to pressure their kids too much and to let them rest when they are not feeling well.

Opinions vary: although some on Chinese social media say it's very thoughtful for hospitals to set up areas where kids can study and read, others blame parents for pressuring their kids to do homework at the hospital instead of resting when not feeling well. pic.twitter.com/gnQD9tFW2c

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) November 22, 2023

By Manya Koetse, with contributions from Miranda Barnes

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China and Covid19

Repurposing China’s Abandoned Nucleic Acid Booths: 10 Innovative Transformations

Abandoned nucleic acid booths are getting a second life through these new initiatives.

Published

1 year agoon

May 19, 2023

During the pandemic, nucleic acid testing booths in Chinese cities were primarily focused on maintaining physical distance. Now, empty booths are being repurposed to bring people together, serving as new spaces to serve the community and promote social engagement.

Just months ago, nucleic acid testing booths were the most lively spots of some Chinese cities. During the 2022 Shanghai summer, for example, there were massive queues in front of the city’s nucleic acid booths, as people needed a negative PCR test no older than 72 hours for accessing public transport, going to work, or visiting markets and malls.

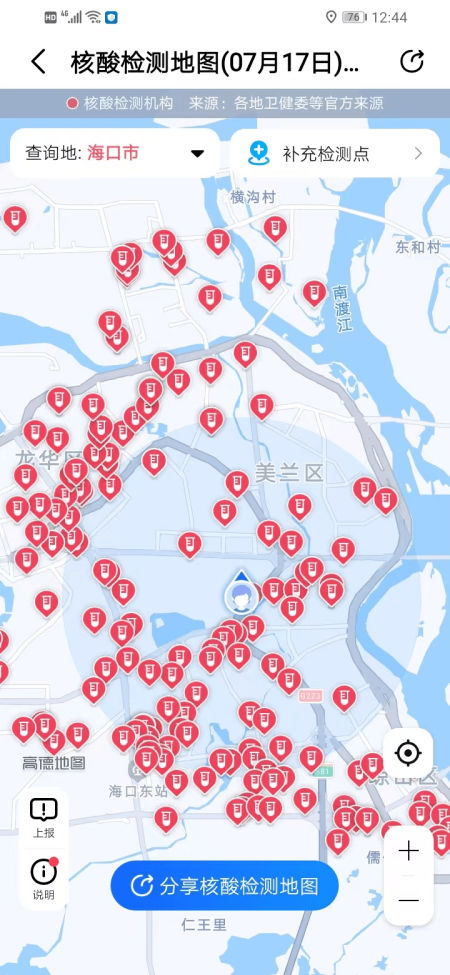

The word ‘hésuān tíng‘ (核酸亭), nucleic acid booth (also:核酸采样小屋), became a part of China’s pandemic lexicon, just like hésuān dìtú (核酸地图), the nucleic acid test map lauched in May 2022 that would show where you can get a nucleic test.

Example of nucleic acid test map.

During Halloween parties in Shanghai in 2022, some people even came dressed up as nucleic test booths – although local authorities could not appreciate the creative costume.

Halloween 2022: dressed up as nucliec acid booths. Via @manyapan twitter.

In December 2022, along with the announced changed rules in China’s ‘zero Covid’ approach, nucleic acid booths were suddenly left dismantled and empty.

With many cities spending millions to set up these booths in central locations, the question soon arose: what should they do with the abandoned booths?

This question also relates to who actually owns them, since the ownership is mixed. Some booths were purchased by authorities, others were bought by companies, and there are also local communities owning their own testing booths. Depending on the contracts and legal implications, not all booths are able to get a new function or be removed yet (Worker’s Daily).

In Tianjin, a total of 266 nucleic acid booths located in Jinghai District were listed for public acquisition earlier this month, and they were acquired for 4.78 million yuan (US$683.300) by a local food and beverage company which will transform the booths into convenience service points, selling snacks or providing other services.

Tianjin is not the only city where old nucleic acid testing booths are being repurposed. While some booths have been discarded, some companies and/or local governments – in cooperation with local communities – have demonstrated creativity by transforming the booths into new landmarks. Since the start of 2023, different cities and districts across China have already begun to repurpose testing booths. Here, we will explore ten different way in which China’s abandoned nucleic test booths get a second chance at a meaningful existence.

1: Pharmacy/Medical Booths

Via ‘copyquan’ republished on Sohu.

Blogger ‘copyquan’ recently explored various ways in which abandoned PCR testing points are being repurposed.

One way in which they are used is as small pharmacies or as medical service points for local residents (居民医疗点). Alleviating the strain on hospitals and pharmacies, this was one of the earliest ways in which the booths were repurposed back in December of 2022 and January of 2023.

Chongqing, Tianjin, and Suzhou were among earlier cities where some testing booths were transformed into convenient medical facilities.

2: Market Stalls

In Suzhou, Jiangsu province, the local government transformed vacant nucleic acid booths into market stalls for the Spring Festival in January 2022, offering them free of charge to businesses to sell local products, snacks, and traditional New Year goods.

The idea was not just meant as a way for small businesses to conveniently sell to local residents, it was also meant as a way to attract more shoppers and promote other businesses in the neighborhood.

3: Community Service Center

Small grid community center in Shizhuang Village, image via Sohu.

Some residential areas have transformed their local nucleic acid testing booths into community service centers, offering all kinds of convenient services to neighborhood residents.

These little station are called wǎnggé yìzhàn (网格驿站) or “grid service stations,” and they can serve as small community centers where residents can get various kinds of care and support.

4: “Refuel” Stations

In February of this year, 100 idle nucleic acid sampling booths were transformed into so-called “Rider Refuel Stations” (骑士加油站) in Zhejiang’s Pinghu. Although it initially sounds like a place where delivery riders can fill up their fuel tanks, it is actually meant as a place where they themselves can recharge.

Delivery riders and other outdoor workers can come to the ‘refuel’ station to drink some water or tea, warm their hands, warm up some food and take a quick nap.

5: Free Libraries

image via sohu.

In various Chinese cities, abandoned nucleic acid booths have been transformed into little free libraries where people can grab some books to read, donate or return other books, and sit down for some reading.

Changzhou is one of the places where you’ll find such “drifting bookstores” (漂流书屋) (see video), but similar initiatives have also been launched in other places, including Suzhou.

6: Study Space

Photos via Copyquan’s article on Sohu.

Another innovative way in which old testing points are being repurposed is by turning them into places where students can sit together to study. The so-called “Let’s Study Space” (一间习吧), fully airconditioned, are opened from 8 in the morning until 22:00 at night.

Students – or any citizens who would like a nice place to study – can make online reservations with their ID cards and scan a QR code to enter the study rooms.

There are currently ten study booths in Anji, and the popular project is an initiative by the Anji County Library in Zhejiang (see video).

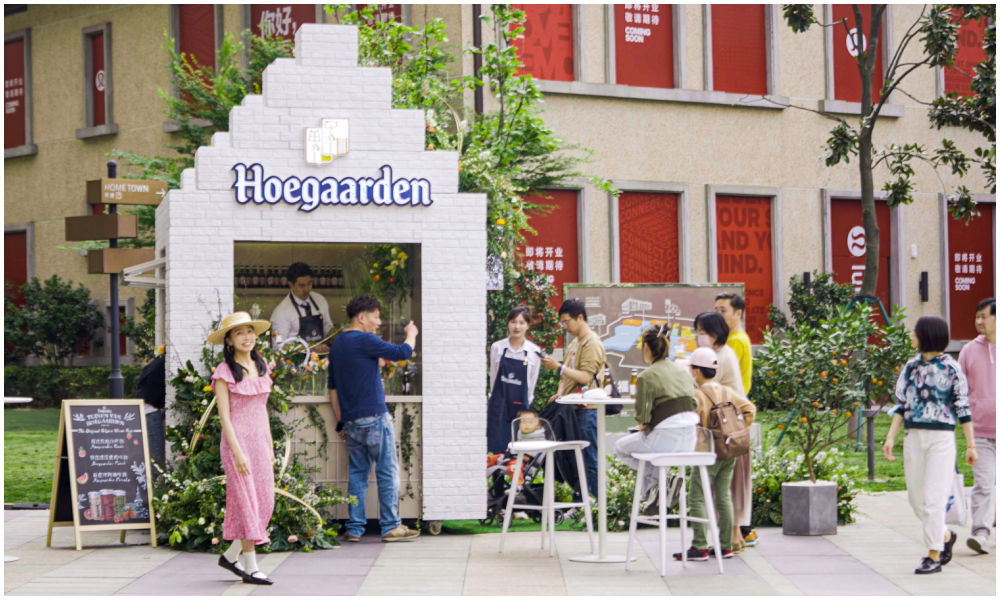

7: Beer Kiosk

Hoegaarden beer shop, image via Creative Adquan.

Changing an old nucleic acid testing booth into a beer bar is a marketing initiative by the Shanghai McCann ad agency for the Belgium beer brand Hoegaarden.

The idea behind the bar is to celebrate a new spring after the pandemic. The ad agency has revamped a total of six formr nucleic acid booths into small Hoegaarden ‘beer gardens.’

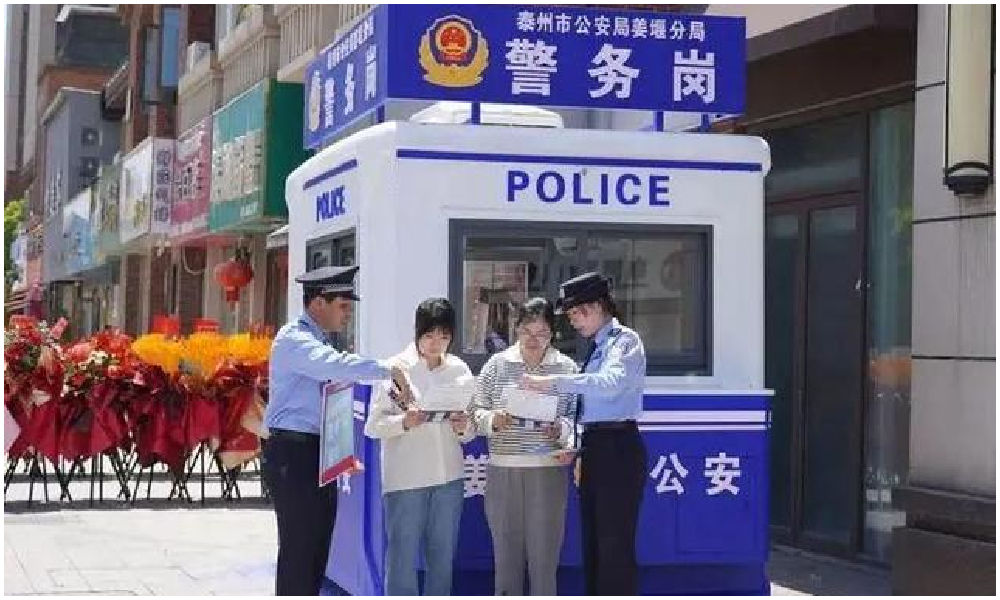

8: Police Box

In Taizhou City, Jiangsu Province, authorities have repurposed old testing booths and transformed them into ‘police boxes’ (警务岗亭) to enhance security and improve the visibility of city police among the public.

Currently, a total of eight vacant nucleic acid booths have been renovated into modern police stations, serving as key points for police presence and interaction with the community.

9: Lottery Ticket Booths

Image via The Paper

Some nucleic acid booths have now been turned into small shops selling lottery tickets for the China Welfare Lottery. One such place turning the kiosks into lottery shops is Songjiang in Shanghai.

Using the booths like this is a win-win situation: they are placed in central locations so it is more convenient for locals to get their lottery tickets, and on the other hand, the sales also help the community, as the profits are used for welfare projects, including care for the elderly.

10: Mini Fire Stations

Micro fire stations, images via ZjNews.

Some communities decided that it would be useful to repurpose the testing points and turn them into mini fire kiosks, just allowing enough space for the necessary equipment to quickly respond to fire emergencies.

Want to read more about the end of ‘zero Covid’ in China? Check our other articles here.

By Manya Koetse,

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

Heiko khoo

December 1, 2022 at 6:43 pm

I am a journalist with an opinion column on China.org.cn since 2009. (http://www.china.org.cn/opinion/heikokhoo.htm) On 5 November 2020 I was arrested while covering an anti-lockdown protest in London. More than 150 people were arrested. I was bundled to the floor by more than 10 police officers, handcuffed and carried 400 meters in a circle of 30 officers with cuffs behind my back which caused bad bruising and injuries to the Charing Cross police station. There I was detained from 9pm to 5am. I was not charged with any crime. I never received an apology and members of the National Union of Journalists complained about my treatment. My journalist card was clearly on display and I told the police again and again that I am a journalist.

After this I was arrested another 6 times over several months on other anti-lockdown demonstrations.