China and Covid19

The Big List of Chinese Covid-19 Pandemic Lexicon: Before, During, and After ‘Zero Covid’

China’s Covid-19 Vocabulary: a glossary of key terms that matter in China’s Covid era, from start to end [premium content].

Published

2 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT

Over the past three years, the Chinese epidemic situation has shaped lives and language. China’s fight against the virus has brought a lot of Covid-19 terms and words, and since China has gone from ‘Zero Covid’ to ‘Opening Up,’ there have been many new words. Here is a glossary of China’s Covid-19 terms by What’s on Weibo.

There are so many words and terms that are used on Chinese social media and in official media in the past years that are new and only make sense in the context of the pandemic and China’s fight against the virus.

Now that China’s epidemic situation is seeing a new phase, and the country is going from one extreme to the other, new words are again being introduced.

It is therefore high time to make up the balance of the words that were used, the terms that were important and have become ingrained in China’s present-day vocabulary, and the recent terms that have been added to the ever-growing Chinese (Mandarin) epidemic lexicon.

Please note that this list does not necessarily give literal translations of each word, but tries to explain what these words mean in the context of the epidemic situation. Many words have taken on a new meaning during the Covid era.

The dictionary translation for the word 清零 qīnglíng, for example, is ‘to clear’ something or ‘to reset.’ But in the context of China’s Covid situation, it has come to be used to refer to the country’s Zero Covid policy, even if the word ‘Covid’ or ‘policy’ are not even included in the term.

The same goes for many other terms in this list. The term 躺平 tǎngpíng basically just means to ‘lie flat’ and it was initially used for a trend among Chinese young people who are fed up with the competitive rat race in China’s job market and education, and only want to do the bare minimum because they believe that upward social mobility has become an unattainable goal.

But since ‘Zero Covid,’ the word ‘lying flat’ was adopted by Chinese state media and started to be used in a different way from when it was used by young people to address their views on life. Instead, it was used as a word that referred to completely giving up the fight against Covid, and taking no measures at all (something which definitely had to be avoided at all costs) (for more about ‘Lying Flat’, read this article.)

And so, simple words such as ‘sheep’ [Covid-positive person] or ‘graduation’ [being allowed to leave a quarantine location], have come to mean wildly different things in the context of China’s epidemic situation.

Here’s our list (which is still being updated, so please bear with us!).

1. THE START OF THE EPIDEMIC AND THE ‘NEW NORMAL’

2019冠狀病毒 2019 Guānzhuàng bìngdú

2019 Coronavirus; Covid-19.

本土新增病例 Běntǔ xīnzēng bìnglì

New Local Infections.

常态化 Chángtàihuà

Normalize.

重启 Chóngqǐ

Restart; reopen. This term was also used when Wuhan ‘restarted’ in spring of 2020 (read more).

复工复产 Fùgōng fùchǎn

Resumption of work and production. After the Wuhan outbreak, Chinese authorities started talking about a resumption of work and production in February of 2020. In April of that year, the central government held a meeting and stated that the resumption of work and production was almost back to normal.

公共卫生 Gōnggòng wèishēng

Public health.

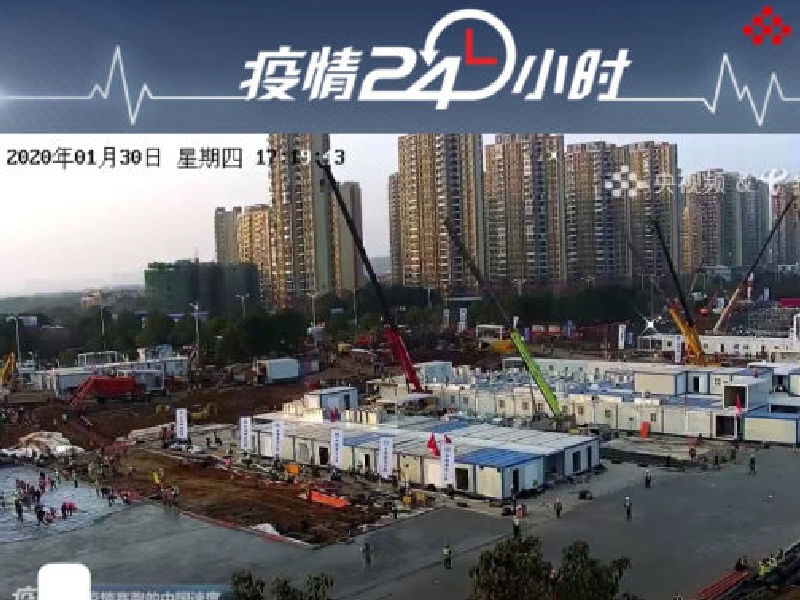

方舱医院 Fāngcāng yīyuàn

Square-cabin hospital; makeshift hospitals. In February of 2020, the impressive construction of two enormous emergency field hospitals in Covid-stricken Wuhan captured the world’s attention. The Huoshenshan and Leishenshan Hospitals were constructed in a matter of days and combined they could take in 2,500 patients. After Wuhan, the ‘fangcang’ became a new phenomenon in Covid China, referring to centralized isolation sites for Covid-positive patients (read more here).

防疫检查 Fángyì jiǎnchá

Epidemic prevention inspection.

防疫人员 Fángyì rényuán

Epidemic prevention staff (later also nicknamed 大白 dàbái).

封城 Fēngchéng

City lockdown.

国务院联防联控工作机制 Guówùyuàn liánfáng liánkòng gōngzuòjīzhì

The Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council, launched in Jan 2020;

an institutional arrangement made by the Chinese government, focusing on the mission of epidemic prevention and control.

健康管理 Jiànkāng guǎnlǐ

Health management.

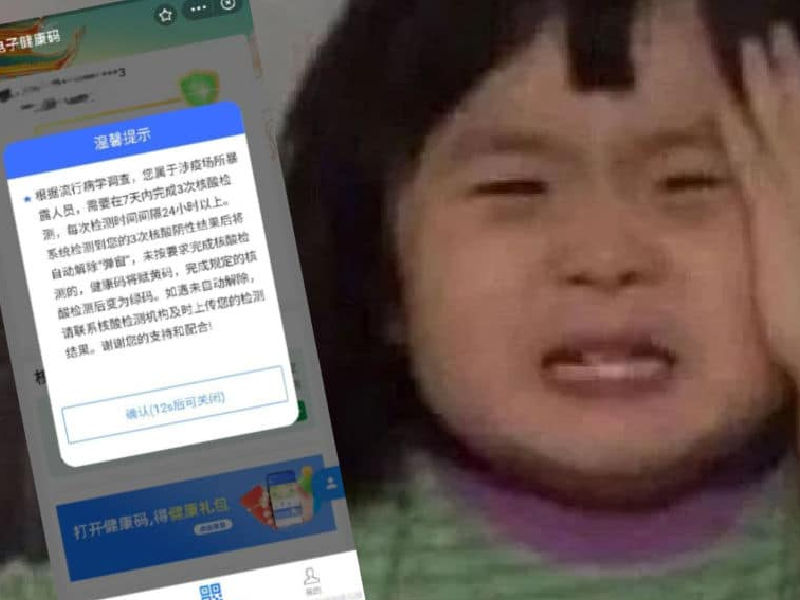

健康码 Jiànkāng mǎ

Health Code. Within eight weeks after the start of the initial Wuhan Covid outbreak, Alibaba (on Alipay) and Tencent (on WeChat) developed and introduced the ‘Health Code,’ a system that gives individuals colored QR codes based on their exposure risk to Covid-19 and serves as an electronic ticket to enter and exit public spaces, restaurants, offices buildings, etc., and to travel from one area to another (read more here).

解封 Jiěfēng

Lift the lockdown. “Wuhan Lifts the Lockdown” (#武汉解封#) went trending on Chinese social media in April of 2020 after the city reopened, celebrating the event with a spectacular midnight light show.

就地过年 Jiùdì guònián

Staycation; staying put for the holidays. Refers to people staying home for Chinese New Year instead of traveling long distance to spend the Spring Festival with their family. This word became especially relevant during the Spring Festival of 2021 (read more).

口罩 Kǒuzhào

Face mask.

逆行者 Nìxíngzhě

Those fighting back. This is a buzzword from 2020 often used by state media to describe frontline workers and others as the ‘people going backward’, referring to those who dare to go back and face problems when everyone else is turning away.

气溶胶 Qìróngjiāo

Aerosols.

人际交往 Rénjì jiāowǎng

Interpersonal Interaction; Social contact.

人民至上 Rénmín zhìshàng

“Put the people in the first place.” As explained in this article by What’s on Weibo, Chinese President Xi Jinping made a speech in May of 2020 including a segment about “our people come first, people’s lives come first, and the safety and health of our people should be secured at all costs.” “Put the people in the first place” has since become a widely circulated slogan and guiding principle for government and society to combat Covid-19 across the country.

社交距离 Shèjiāo jùlí

Social distance.

新冠肺炎 Xīnguān fèiyán

Novel Coronavirus; New Corona pneumonia.

新型冠状病毒 Xīnxíng guānzhuàng bìngdú

New Coronavirus; Covid-19.

疫情 Yìqíng

Epidemic.

疫情期间 Yìqíng qíjiān

During the epidemic.

远程办公 Yuǎnchéng bàngōng

Working from home.

娱乐场所 Yúlè chǎngsuǒ

Places of entertainment.

云监工 Yún jiāngōng

‘Cloud Supervisor.’ This a new word to refer to the people “supervising” (i.e. witnessing and cheering for) the rapid construction of the Huoshenshan and Leishenshan makeshift hospitals in Wuhan via the government’s cloud online streaming of the construction site.

网课 Wǎng kè

Online classes.

无接触配送 Wú jiēchù pèisòng

Contactless delivery.

无症状 Wúzhèngzhuàng

Asymptomatic.

无症状感染者 Wúzhèngzhuàng gǎnrǎnzhě

Asymptomatic infected person. This refers to people who test positive for Covid but show no clinical symptoms (this is different from 确诊病例 quèzhěn bìnglì, a confirmed Covid case showing symptoms).

行程码 Xíngchéngmǎ

Travel Code. Full word is 通信大数据行程卡, ‘Telecommunications Big Data Travel Card,’ better known as the ‘green arrow code,’ which tracks users’ travel history and is also available inside WeChat or can be downloaded as a standalone app. Its goal is to track if you’ve been to any medium or high-risk areas over the past 14 days. The Travel Code was officially taken offline on December 13, 2022.

直播带货 Zhíbò dàihuò

Livestream commerce. Live streaming commerce was already popular in China, and the epidemic pushed the popularity of shopping by watching livestreams to the next level.

2. ZERO COVID ERA

爱心蔬菜礼包 Àixīn shūcài lǐbāo

So-called ‘Grocery care packages,’ also 大礼包 dàlǐbāo, are some grocery supplies provided by the government. These ‘care packages’ became a ubiquitous phenomenon in many areas across China where people were in high-risk, locked-down areas. While many struggled to get (online) groceries at normal prices, local governments sent out boxes or bags filled with vegetables, meat, noodles, fruit and snacks to make sure households had some food to get them through the next few days.

被封闭 Bèi fēngbì

Being locked down.

被弹窗 Bèi dànchuāng

Getting popped up. This phenomenon happens when residents receive a much-dreaded “pop-up message” on their mobile phone via their Health Code app. This means that the app – through the use of big data and the monitoring of people’s status and movements – has determined that you’re a possible contagion risk based on where you went at what time. People who received the pop-up message are supposed to report to their community/hotel/school so that the relevant departments can conduct a “risk check.” The pop-up window will not disappear until individuals are officially no longer considered a contagion risk (read more).

被拉走 Bèi lāzǒu

Being dragged away; taken off. This word was especially used during the Xi’an lockdown when people expressed fears of being taken away to a centralized quarantine location after the sudden quarantine of the city’s Mingde Bayingli Community.

闭环管理 Bìhuán guǎnlǐ

Closed loop management. The ‘Covid-19 closed-loop management’ (新冠疫情闭环管理) has been applied to various areas when there were new local cases of COVID-19. It means that people belonging to a certain (work) group are only allowed to move between designated venues for work, living, eating, through a dedicated transport system. This word became especially known because the 2022 Olympics in China also used this style (read here).

闭环作业的高风险岗位 Bìhuán zuòyè de gāo fēngxiǎn gǎngwèi

High-risk positions in closed-loop operations.

毕业 Bìyè

‘Graduate.’ In Covid times, this term was used by patients who were allowed to leave the Fangcang (quarantine hospital).

仓主 Cāngzhǔ

Someone who is at a Fangcang (quarantine hospital).

出舱 Chūcāng

Leaving the fangcang. Also referred to as a ‘graduation’ 毕业 (Bìyè).

春耕证 Chūngēngzhèng

‘Spring Ploughing Permit.’ This is a permit that was introduced in rural areas in Covid lockdown times to allow local farmers to go out into the fields to work despite epidemic restrictions.

大白 Dàbái

Big white; anti-epidemic worker. In early 2022, the anti-epidemic workers dressed in white hazmat suits were more commonly referred to as ‘dàbái,’ an and affectionate nickname that literally means “big white.” In the Chinese version of the 2014 Disney movie Big Hero 6, the healthcare-robot Baymax is also called Dàbái. For more about public attitudes toward dabai in early 2022, see this article.

单独舱室的集中隔离点 Dāndú cāngshì de jízhōng gélídiǎn

‘Separate Compartment Concentrated Isolation Point’; isolation site with separated cabins. Also known as “单人单间”集中隔离 [“Dānrén dānjiān” jízhōng gélí, lit “Single room” Centralized Isolation] or 单人单间隔离 [Dānrén dānjiàn gélí, Single Room Isolation].

单人单管 Dānrén dānguǎn

Individual test; single tube test. This is a single, individual Covid test whereas ‘pooled sample testing’ (see 混合采样 hùnhé cǎiyàng) takes samples from multiple people, storing the result in batches, or pools, and then testing each pool.

点式复工 Diǎnshì fùgōng

Point-based work resumption. An active policy introduced in spring of 2022 for people holding key positions at companies within the non-manufacturing sector that are resuming work. According to the ‘point-to-point’ (点对点) strategy, employees are either staying within the closed loop of their workplace or within the premises of their community. They can only return to their workplace once a month, and are not allowed to stay longer than one week (read more).

低风险地区 Dī fēngxiǎn dìqū

Low risk area, which is the lowest classification compared to “medium-risk areas” 中风险地区 and “High-risk areas” 高风险地区.

动态清零 Dòngtài qīnglíng

Dynamic zero; Dynamic Zero Covid policy.

囤货模式 Dùnhuò móshì

Hoarding mode. Referring to the panic buying taking place in several places, such as in Chengdu, right before a lockdown.

方舱隔离点 Fāngcāng gélídiǎn

Fangcang isolation point; quarantine center.

放毒 Fàngdú

Spreaders. Negative online slang word to refer to ‘spreaders’, those Covid-positive persons who infect others. The word fàngdú literally means to poison or to spread malicious rumors.

非必要不出门 Fēi bìyào bù chūmén

Do not go out unless necessary.

封锁式隔离 Fēngsuǒshì gélí

Locked isolation.

高风险地区 Gāo fēngxiǎn dìqū

High-risk district.

高风险区外溢人员 Gāo fēngxiǎnqū wàiyì rényuán

People who come from a high-risk area (return).

隔离点 Gélí diǎn

Isolation point.

隔离方舱 Gélí fāngcāng

Isolation Fangcang.

隔离围挡 Gélí wéidǎng

Isolation fence.

共存派 Gòngcúnpài or 开放派 Kāifàng pài

The group of people in society who want to open up and live together with the virus. They’re the opponents of the 清零派 qīnglíngpài, who oppose opening up the country and advocate persisting in the fight against Covid.

核酸检测 Hésuān jiǎncè

Nucleic acid test; RT-PCR test. Not to be confused with the Rapid PCR test or antigen test (抗原检测 kàngyuán jiǎncè).

核酸点位 Hésuān diǎnwèi

Nucleic acid test site.

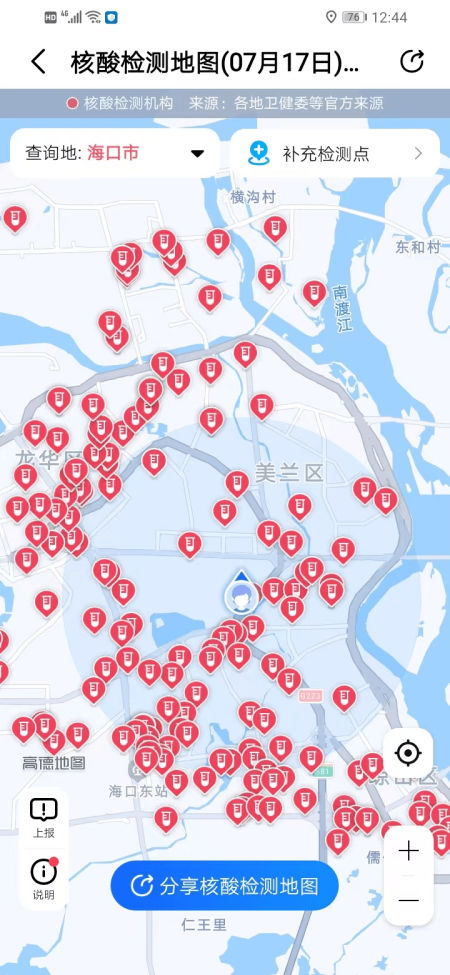

核酸地图 Hésuān dìtú

Nucleic acid test map. A map that shows where you can get a nucleic test. Officially launched by Gaode in May of 2022.

核酸亭 Hésuān tíng

Nucleic acid booth. Also called: hésuān cǎiyàng xiǎowū (核酸采样小屋), ‘nucleic acid sampling cabin’

核酸阴性检测证明 Hésuān yīnxìng jiǎncè zhèngmíng

Negative nucleic acid test certificate.

混合采样 Hùnhé cǎiyàng

Pooled sample testing; Mixed testing; also called 混采 hùncǎi. Nucleic acid testing is done as single or mixed according to the risk level of the target population. For example, those in quarantine locations or high-risk areas will always be tested individually but when the area is low risk, ten or twenty results can be mixed and tested together. When paying for own tests, pooled testing is also cheaper.

检查站 Jiǎncházhàn

Checkpoint.

静默管理 Jìngmò guǎnlǐ

Quiet management; silent management. This concept was introduced as a ‘soft lockdown’ but it is actually also a pretty strict, region-wide static management, which allows people to only leave their homes, units, or communities for nucleic acid testing, or unless absolutely necessary. The purpose is to prevent people to leave their homes for non-essential matters in order to quickly trace down new infections and to prevent Covid from spreading beyond a high-risk area.

静态管理 Jìngtài guǎnlǐ

Static management. This is a kind of lockdown that is stricter than ‘quiet management’ (静默管理 jìngmò guǎnlǐ) and severely limits the flow of people and vehicles in a high-risk area, and suspends all businesses in the area except for supermarkets, pharmacies, and medical institutions.

精准防控 Jīngzhǔn fángkòng

Precise prevention and control.

集中隔离 Jízhōng gélí

Centralized isolation.

居家静止 Jūjiā jìngzhǐ

‘Home lockdown’; ‘Home standstill.’ Another word to describe a lockdown during China’s Zero Covid, where there have been many different words to describe similar measures (also: 全域静默, 静态管理, 停止一切非必要人员流动).

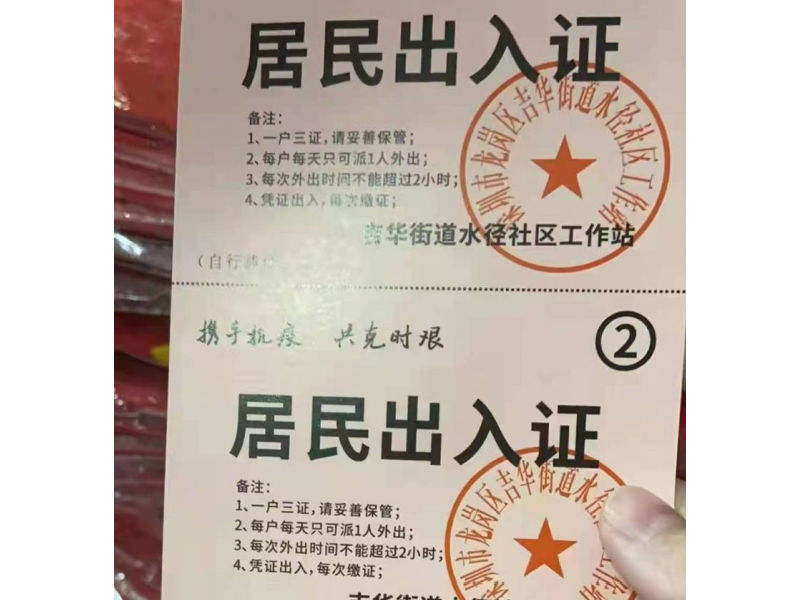

居民出入证 Jūmín chūrù zhèng

Residents’ entrance and exit permit. During lockdowns, this permit allowed residents to go out once per day (one person per household) for two hours, allowing residents to do essntial shopping or other activities.

科学精准 Kēxué jīngzhǔn

Scientific and precise. Used in the context of carrying out epidemic prevention measures in a scientific and precise manner.

临时被封闭 Línshí bèi fēngbì

Temporarily locked down.

绿马 Lǜmǎ

Green horse. ‘Green Horse’ in Chinese sounds exactly the same as the word for ‘green code’ (绿码), referring to the green QR code in China’s Covid health apps. The phrase “Bàozhù lǜmǎ” (抱住绿码/马) became popular on Chinese social media, a wordplay meant to mean both “Keep your code green” as well as “Hold on to your Green Horse” (read more).

密切接触者 Mìqiè jiēchùzhě

Close contact.

密接的密接 Mìqiè de mìqiè

Close contacts of close contacts. This is just one among the many words to label those who have might come across someone who tested positive for Covid in various ways (密接、二代密接、次次密接、次次次密接、一般接触者、同性密接、异性密接、同城密接、同层密接、同楼密).

强制隔离 Qiángzhì gélí

Mandatory quarantine.

清零 Qīnglíng or 清零政策 Qīnglíng zhèngcè

Zero Covid policy.

清零派 Qīnglíngpài

The “Zero School”, or the “Zero Covid Faction”, referring to those people who oppose opening up the country and advocate persisting in the fight against Covid. They’re the opponents of the 共存派 gòngcúnpài or 开放派 kāifàng pài, who advocate opening up and living together with the virus.

气泡式管理 Qìpào shì guǎnlǐ

Bubble-style management. This term was especially used for the Winter Olympics, where participants were only allowed to move between Games-related venues for their training, catering, accommodation, etc. through a dedicated Games transport system. Participants were not allowed to leave their designated areas. But the term also popped up again in May of 2022 to announce new measures in order to allow production to continue at factories and other businesses (read more).

全员核酸筛查 Quányuán hésuān shāichá

Nucleic screenings for Covid.

入境航班熔断机制 Rùjìng hángbān róngduàn jīzhì

Circuit breaker measures for scheduled international passenger flights. To prevent the cross-border spread of Covid-19, the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) issued an official notice on the Adjustment of the Circuit Breaker Measures for International Passenger Flights, which imposed circuit-breaker measures on scheduled international passenger flights with a high risk of spreading the pandemic, from 8 June 2020. The so-called “circuit breaking mechanism” under which China-bound flight routes were suspended for two weeks if an airline was found to carry a certain number of passengers testing positive for Covid was abolished in November of 2022.

社会面清零 Shèhuìmiàn qīnglíng

Zero covid on the society level; safe social surface. This is a word that was mainly used during ‘zero Covid’ in 2022 and refers to a degree of control on the spread of Covid within the communities. This means that all those who test positive are in isolation or within closed-loop systems and that they are unable to infect others, which is equivalent to a ‘safe social surface.’ This word was also used when the big Xi’an outbreak was largely contained in the city’s main communities after two weeks of lockdown, during which over 42,000 people were quarantined and brought to other locations.

时空伴随者 Shíkōng bànsuízhě

‘Time-space Company.’ Refers to those who have been near a confirmed Covid patient in time and space; meaning that within a time frame of fourteen days a person has spent more than ten minutes with a confirmed Covid case within a distance of 800 meters. This means the ‘Health Code’ could turn to yellow.

四早 Sì zǎo

Four early: early detection, early reporting, early isolation, early treatment

躺平派 Tǎngpíngpài

The ‘lie flat group,’ referring to those who want to give up all measures and give up the fight against Covid. ‘Lying flat’ (tǎngpíng) is a word that has been around for much longer but it has come to take on a different meaning during the pandemic. For more about China’s Lying Flat momevement, check our article here.

铁网 Tiěwǎng

Fenced.

通行证 Tōng xíng zhèng

Pass to enter. In Covid times, this mainly refers to a permit to allow cross-provincial travel and business (i.e. freight vehicles and such).

围合管理 Wéi hé guǎnlǐ

Enclosed managament. This officially is not a ‘lockdown’ but it means that a certain residential area of community is fenced off, with checkpoints at the community entrance and exit. Both people and vehicles can enter and exit with a permit. People who do not live or work in the enclosed area are not allowed to enter.

严防 Yánfáng

Take strict measures.

羊/🐑 Yáng

Literally means ‘sheep’ but has come to be used to refer to someone who tested positive for Covid, since the word for ‘positive’ (阳) sounds the same.

阳了 Yáng le

Tested positive.

阳性 Yángxìng

Covid Positive.

疑似病例 Yísì bìnglì

Suspected case.

永久性方舱医院 Yǒngjiǔxìng fāngcāng yīyuàn

Permanent shelter hospitals; permanent fangcang hospitals. This term was introduced in May of 2022 and is somewhat contradictory as a concept, since ‘Fangcang hospitals’ are actually defined by their temporary nature. The term came up when Chinese authorities emphasized the need for China’s bigger cities to build or renovate existing makeshift Covid hospitals, and turn them into permanent sites (read more).

原则居家 Yuánzé jūjiā

Stay at home in principle; Ordered stay-at-home. Term used authorities instead of ‘lockdown’ in the second half of 2022.

硬隔离 Yìng gélí

Hard isolation; Fenced isolation. While some Shanghai households had already endured weeks of isolation, a new word was added to their epidemic vocabulary in April of 2022: ‘hard isolation’ or ‘strong quarantine.’ The word popped up on Chinese social media on April 23rd after some Shanghai netizens posted photos of fences being set up around their community building to keep residents from walking out. Read more about ‘hard isolation’ here.

应检尽检 Yīng jiǎn jǐn jiǎn

Whoever should be tested, should be tested as much as possible; all those who need it, need to be tested.

医院非绿码医疗救治 Yīyuàn fēi lǜmǎ yīliáo jiùzhì

Non-green code medical treatment. Referring to the medical treatment of those whose Health Code apps do not show a ‘green code’, meaning they potentially are at risk of having been in contact with someone who is Covid-positive. (Also: “非绿码”患者的医疗救治.)

小阳人 Xiǎo yángrén

Little positive people, also little sheep people; used to refer to people who tested positive for Covid in a joking and somewhat deregatory way.

新冠肺炎疫情地图 Xīnguān fèiyán yìqíng dìtú

Covid outbreak map, also: ‘epidemic map’ 疫情地图 yìqíng dìtú.

暂时隔离 Zhànshí gélí

Temporary isolation / lockdown.

中风险地区 Zhòng fēngxiǎn dìqū

Medium-risk area.

自我隔离点 Zìwǒ gélí diǎn

Self-isolation site.

做核酸 Zuò hésuān

Do a nucleic acid test.

3. POST ZERO COVID

奥密克戎病毒 Àomìkèróng bìngdú

Omicron Virus.

布洛芬 Bùluòfēn

Ibuprofen.

长期新冠 Chángqí xīnguān

Long Covid.

初阳权 Chū yáng quán

‘The privilege to infect someone.’ This word, which went trending on Chinese social media in December of 2022, consists of three characters literally meaning ‘first positive right.’ At a time when one person after the other tests positive for Covid, it is an ongoing joke about who has the privilege to infect another person with Covid. It is a wordplay on 初夜权 chūyè quán, ‘right of the first night’ (droit du seigneur), and – tongue in cheek – suggests that nobody else but the husband has the right to infect their wife with Omicron. The main idea is that everyone will inevitably get infected anyway, so it’s better the be infected by someone you love.

毒株 Dúzhū

Virus strain.

发烧 Fāshāo

Run a fever.

复阳 Fùyáng

To test positive again. This word, which literally means ‘repeat positive,’ is not the same as being ‘reinfected’ or getting Covid a second time. Instead it refers to testing positive after initially testing negative, with a likely reason being that the body has not cleared the virus yet.

发热门诊 Fārè ménzhěn

Fever clinics.

感染高峰 Gǎnrǎn gāofēng

Infection peak.

黄桃罐头 Huángtáo Guàntóu

Canned yellow peaches. One of the ‘food remedies’ that became exceptionally popular during the Covid outbreak (read more).

加强针 Jiāqiáng zhēn

Booster shot.

检测结果呈阳性 Jiǎncè jiéguǒ chéng yángxìng

Positive Covid test.

急诊室 Jízhěn shì

Emergency room.

急转弯 Jízhuǎnwān

Sudden turn; sharp turn. Often used in the context of the shift from zero Covid policy to easing measures.

居家隔离 Jūjiā gélí

Home isolation; home quarantine.

居家健康监测 Jūjiā jiànkāng jiāncè

Home health monitoring.

抗原检测 Kàngyuán jiǎncè

Antigen test.

连花清瘟 Lianhua Qingwen

Traditional Chinese medicine Lianhua Qingwen (连花清瘟), a herbal pill by Yiling Pharmaceuticals which is used for the treatment of influenza as well as Covid.

盲目囤药 Mángmù dùnyào

Blindly hoarding medicine.

临时接种点 Línshí jiēzhǒngdiǎn

Temporary vaccination sites.

流动接种车 Liúdòng jiēzhǒngchē

Mobile vaccination vans.

绿色通道 Lǜsè tōngdào

Green channels (for vaccination). Meant to speed up vaccination rates among the eldery by giving them priority status.

盲目吃药 Mángmù chī yào

Take medicine blindly; take too many medicines or to take them the wrong way.

免疫系统 Miǎnyì xìtǒng

Immune system.

免疫力 Miǎnyìlì

Immunity.

前疫情时代 Qián yìqíng shídài

Pre-pandemic era.

全面放开 Quánmiàn fàngkāi

Full liberalization; complete opening-up.

唐飞 Tángfēi

This word refers to the two sides in Chinese society when it comes to Covid policies, with one supporting ‘zero Covid’ while the other side advocates living together with the virus and opening up. The first group calls the others 躺匪 tǎngfěi, ‘lying bandits’ (who support ‘lying flat’ and living with the virus), of which the pronunciation in standard Chinese is similar to 唐飞 tángfēi, a homophone which has come to be used as online slang.

退烧 Tuìshāo

Reduce fever.

吞刀片 Tūn dāopiàn

Swallowing blades. One of the well-known Covid-19 symptoms where the throat feels so painful that netizens have come to describe it as “swallowing blades,” which has now become a common way to describe the symptom.

新十条 Xīn shítiáo

Ten new rules. Referring a 10-point plan addressing changes in Covid measures, and basically annoucning the end of ‘Zero Covid’ (read more here).

阳康 Yángkāng

Recover from Covid. This word is a combination of 阳 yáng, meaning [to test] ‘positive,’ and the word 康 kāng meaning ‘healthy.’ The word is also a pun based on a fictional character in Jin Yong’s The Legend of the Condor Heroes martial novel, namely 杨康 Yáng Kāng (read more).

优化核酸检测 Yōuhuà hésuān jiǎncè

Optimized nucleic acid testing.

政治出柜 Zhèngzhì chūguì

Political coming-out. This term came up after the protests of November 2022 and refers to people showing their political position or views to those around them, usually in social media settings. It mostly refers to ‘coming out’ about being pro-opening up or for sticking with ‘zero Covid.’ Read more here.

自费采样点 Zìfèi cǎiyàng diǎn

Self-paid testing point.

(This article is still being updated.)

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China and Covid19

Sick Kids, Worried Parents, Overcrowded Hospitals: China’s Peak Flu Season on the Way

“Besides Mycoplasma infections, cases include influenza, Covid-19, Norovirus, and Adenovirus. Heading straight to the hospital could mean entering a cesspool of viruses.”

Published

8 months agoon

November 22, 2023

In the early morning of November 21, parents are already queuing up at Xi’an Children’s Hospital with their sons and daughters. It’s not even the line for a doctor’s appointment, but rather for the removal of IV needles.

The scene was captured in a recent video, only one among many videos and images that have been making their rounds on Chinese social media these days (#凌晨的儿童医院拔针也要排队#).

One photo shows a bulletin board at a local hospital warning parents that over 700 patients are waiting in line, estimating a waiting time of more than 13 hours to see a doctor.

Another image shows children doing their homework while hooked up on an IV.

Recent discussions on Chinese social media platforms have highlighted a notable surge in flu cases. The ongoing flu season is particularly impacting children, with multiple viruses concurrently circulating and contributing to a high incidence of respiratory infections.

Among the prevalent respiratory infections affecting children are Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections, influenza, and Adenovirus infection.

The spike in flu cases has resulted in overcrowded children’s hospitals in Beijing and other Chinese cities. Parents sometimes have to wait in line for hours to get an appointment or pick up medication.

According to one reporter at Haibao News (海报新闻), there were so many patients at the Children’s Hospital of Capital Institute of Pediatrics (首都儿科研究所) on November 21st that the outpatient desk stopped accepting new patients by the afternoon. Meanwhile, 628 people were waiting in line to see a doctor at the emergency department.

Reflecting on the past few years, the current flu season marks China’s first ‘normal’ flu peak season since the outbreak of Covid-19 in late 2019 / early 2020 and the end of its stringent zero-Covid policies in December 2022. Compared to many other countries, wearing masks was also commonplace for much longer following the relaxation of Covid policies.

Hu Xijin, the well-known political commentator, noted on Weibo that this year’s flu season seems to be far worse than that of the years before. He also shared that his own granddaughter was suffering from a 40 degrees fever.

“We’re all running a fever in our home. But I didn’t dare to go to the hospital today, although I want my child to go to the hospital tomorrow. I heard waiting times are up to five hours now,” one Weibo user wrote.

“Half of the kids in my child’s class are sick now. The hospital is overflowing with people,” another person commented.

One mother described how her 7-year-old child had been running a fever for eight days already. Seeking medical attention on the first day, the initial diagnosis was a cold. As the fever persisted, daily visits to the hospital ensued, involving multiple hours for IV fluid administration.

While this account stems from a single Weibo post within a fever-advice community, it highlights a broader trend: many parents swiftly resort to hospital visits at the first signs of flu or fever. Several factors contribute to this, including a lack of General Practitioners in China, making hospitals the primary choice for medical consultations also in non-urgent cases.

There is also a strong belief in the efficacy of IV infusion therapy, whether fluid-based or containing medication, as the quickest path to recovery. Multiple factors contribute to the widespread and sometimes irrational use of IV infusions in China. Some clinics are profit-driven and see IV infusions as a way to make more money. Widespread expectations among Chinese patients that IV infusions will make them feel better also play a role, along with some physicians’ lacking knowledge of IV therapy or their uncertainty to distinguish bacterial from viral infections (read more here)

To prevent an overwhelming influx of patients to hospitals, Chinese state media, citing specialists, advise parents to seek medical attention at the hospital only for sick infants under three months old displaying clear signs of fever (with or without cough). For older children, it is recommended to consult a doctor if a high fever persists for 3 to 5 days or if there is a deterioration in respiratory symptoms. Children dealing with fever and (mild) respiratory symptoms can otherwise recover at home.

One Weibo blogger (@奶霸知道) warned parents that taking their child straight to the hospital on the first day of them getting sick could actually be a bad idea. They write:

“(..) pediatric departments are already packed with patients, and it’s not just Mycoplasma infections anymore. Cases include influenza, Covid-19, Norovirus, and Adenovirus. And then, of course, those with bad luck are cross-infected with multiple viruses at the same time, leading to endless cycles. Therefore, if your child experiences mild coughing or a slight fever, consider observing at home first. Heading straight to the hospital could mean entering a cesspool of viruses.”

The hashtag for “fever” saw over 350 million clicks on Weibo within one day on November 22.

Meanwhile, there are also other ongoing discussions on Weibo surrounding the current flu season. One topic revolves around whether children should continue doing their homework while receiving IV fluids in the hospital. Some hospitals have designated special desks and study areas for children.

Although some commenters commend the hospitals for being so considerate, others also remind the parents not to pressure their kids too much and to let them rest when they are not feeling well.

Opinions vary: although some on Chinese social media say it's very thoughtful for hospitals to set up areas where kids can study and read, others blame parents for pressuring their kids to do homework at the hospital instead of resting when not feeling well. pic.twitter.com/gnQD9tFW2c

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) November 22, 2023

By Manya Koetse, with contributions from Miranda Barnes

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China and Covid19

Repurposing China’s Abandoned Nucleic Acid Booths: 10 Innovative Transformations

Abandoned nucleic acid booths are getting a second life through these new initiatives.

Published

1 year agoon

May 19, 2023

During the pandemic, nucleic acid testing booths in Chinese cities were primarily focused on maintaining physical distance. Now, empty booths are being repurposed to bring people together, serving as new spaces to serve the community and promote social engagement.

Just months ago, nucleic acid testing booths were the most lively spots of some Chinese cities. During the 2022 Shanghai summer, for example, there were massive queues in front of the city’s nucleic acid booths, as people needed a negative PCR test no older than 72 hours for accessing public transport, going to work, or visiting markets and malls.

The word ‘hésuān tíng‘ (核酸亭), nucleic acid booth (also:核酸采样小屋), became a part of China’s pandemic lexicon, just like hésuān dìtú (核酸地图), the nucleic acid test map lauched in May 2022 that would show where you can get a nucleic test.

Example of nucleic acid test map.

During Halloween parties in Shanghai in 2022, some people even came dressed up as nucleic test booths – although local authorities could not appreciate the creative costume.

Halloween 2022: dressed up as nucliec acid booths. Via @manyapan twitter.

In December 2022, along with the announced changed rules in China’s ‘zero Covid’ approach, nucleic acid booths were suddenly left dismantled and empty.

With many cities spending millions to set up these booths in central locations, the question soon arose: what should they do with the abandoned booths?

This question also relates to who actually owns them, since the ownership is mixed. Some booths were purchased by authorities, others were bought by companies, and there are also local communities owning their own testing booths. Depending on the contracts and legal implications, not all booths are able to get a new function or be removed yet (Worker’s Daily).

In Tianjin, a total of 266 nucleic acid booths located in Jinghai District were listed for public acquisition earlier this month, and they were acquired for 4.78 million yuan (US$683.300) by a local food and beverage company which will transform the booths into convenience service points, selling snacks or providing other services.

Tianjin is not the only city where old nucleic acid testing booths are being repurposed. While some booths have been discarded, some companies and/or local governments – in cooperation with local communities – have demonstrated creativity by transforming the booths into new landmarks. Since the start of 2023, different cities and districts across China have already begun to repurpose testing booths. Here, we will explore ten different way in which China’s abandoned nucleic test booths get a second chance at a meaningful existence.

1: Pharmacy/Medical Booths

Via ‘copyquan’ republished on Sohu.

Blogger ‘copyquan’ recently explored various ways in which abandoned PCR testing points are being repurposed.

One way in which they are used is as small pharmacies or as medical service points for local residents (居民医疗点). Alleviating the strain on hospitals and pharmacies, this was one of the earliest ways in which the booths were repurposed back in December of 2022 and January of 2023.

Chongqing, Tianjin, and Suzhou were among earlier cities where some testing booths were transformed into convenient medical facilities.

2: Market Stalls

In Suzhou, Jiangsu province, the local government transformed vacant nucleic acid booths into market stalls for the Spring Festival in January 2022, offering them free of charge to businesses to sell local products, snacks, and traditional New Year goods.

The idea was not just meant as a way for small businesses to conveniently sell to local residents, it was also meant as a way to attract more shoppers and promote other businesses in the neighborhood.

3: Community Service Center

Small grid community center in Shizhuang Village, image via Sohu.

Some residential areas have transformed their local nucleic acid testing booths into community service centers, offering all kinds of convenient services to neighborhood residents.

These little station are called wǎnggé yìzhàn (网格驿站) or “grid service stations,” and they can serve as small community centers where residents can get various kinds of care and support.

4: “Refuel” Stations

In February of this year, 100 idle nucleic acid sampling booths were transformed into so-called “Rider Refuel Stations” (骑士加油站) in Zhejiang’s Pinghu. Although it initially sounds like a place where delivery riders can fill up their fuel tanks, it is actually meant as a place where they themselves can recharge.

Delivery riders and other outdoor workers can come to the ‘refuel’ station to drink some water or tea, warm their hands, warm up some food and take a quick nap.

5: Free Libraries

image via sohu.

In various Chinese cities, abandoned nucleic acid booths have been transformed into little free libraries where people can grab some books to read, donate or return other books, and sit down for some reading.

Changzhou is one of the places where you’ll find such “drifting bookstores” (漂流书屋) (see video), but similar initiatives have also been launched in other places, including Suzhou.

6: Study Space

Photos via Copyquan’s article on Sohu.

Another innovative way in which old testing points are being repurposed is by turning them into places where students can sit together to study. The so-called “Let’s Study Space” (一间习吧), fully airconditioned, are opened from 8 in the morning until 22:00 at night.

Students – or any citizens who would like a nice place to study – can make online reservations with their ID cards and scan a QR code to enter the study rooms.

There are currently ten study booths in Anji, and the popular project is an initiative by the Anji County Library in Zhejiang (see video).

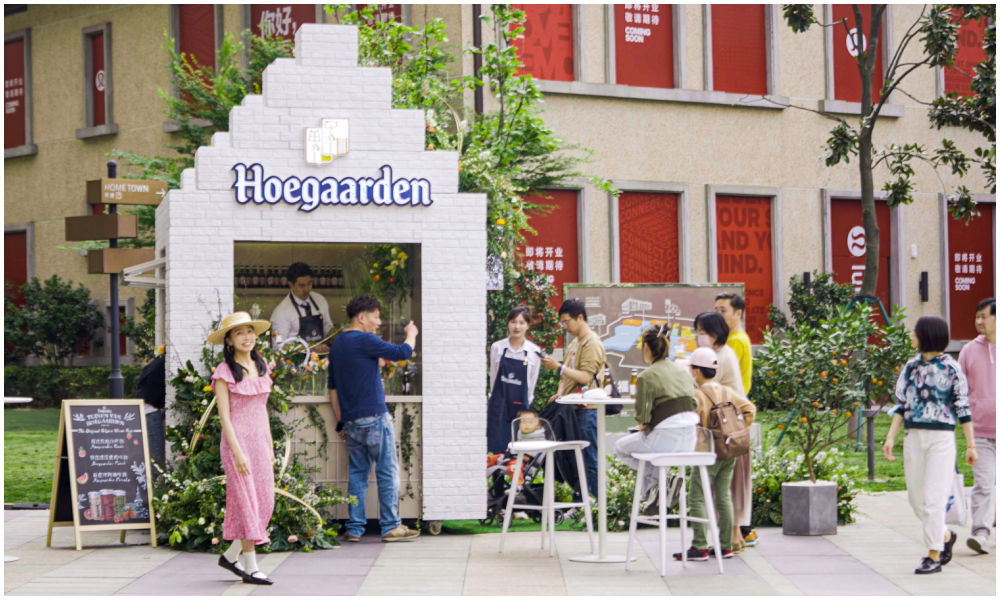

7: Beer Kiosk

Hoegaarden beer shop, image via Creative Adquan.

Changing an old nucleic acid testing booth into a beer bar is a marketing initiative by the Shanghai McCann ad agency for the Belgium beer brand Hoegaarden.

The idea behind the bar is to celebrate a new spring after the pandemic. The ad agency has revamped a total of six formr nucleic acid booths into small Hoegaarden ‘beer gardens.’

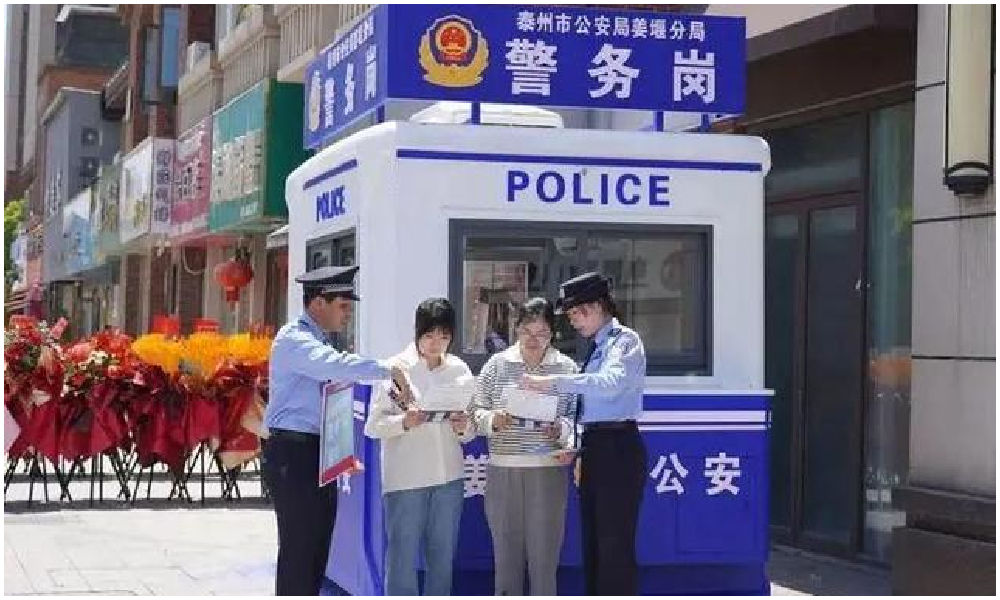

8: Police Box

In Taizhou City, Jiangsu Province, authorities have repurposed old testing booths and transformed them into ‘police boxes’ (警务岗亭) to enhance security and improve the visibility of city police among the public.

Currently, a total of eight vacant nucleic acid booths have been renovated into modern police stations, serving as key points for police presence and interaction with the community.

9: Lottery Ticket Booths

Image via The Paper

Some nucleic acid booths have now been turned into small shops selling lottery tickets for the China Welfare Lottery. One such place turning the kiosks into lottery shops is Songjiang in Shanghai.

Using the booths like this is a win-win situation: they are placed in central locations so it is more convenient for locals to get their lottery tickets, and on the other hand, the sales also help the community, as the profits are used for welfare projects, including care for the elderly.

10: Mini Fire Stations

Micro fire stations, images via ZjNews.

Some communities decided that it would be useful to repurpose the testing points and turn them into mini fire kiosks, just allowing enough space for the necessary equipment to quickly respond to fire emergencies.

Want to read more about the end of ‘zero Covid’ in China? Check our other articles here.

By Manya Koetse,

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?