China and Covid19

Zhejiang Daily: ‘People First’ Does Not Mean ‘Anti-Epidemic First’

Many Chinese netizens are showing support for Zhejiang Daily after the Party newspaper published an article that tries to find a middle ground between what authorities want to say and what ordinary people want to hear.

Published

2 years agoon

After days of unrest, Party newspaper Zhejiang Daily published an article by the Propaganda Department (aka Publicity Department) that addresses the current problems in China’s epidemic situation, talks about the way forward, and stresses the importance of listening to people’s demands and “putting the people first.” But not everyone is convinced.

On Tuesday, November 29, after days filled with unrest and protests in various places across China, Party newspaper Zhejiang Daily (浙江日报) published a noteworthy article titled “‘People First’ Is Not ‘Anti-Epidemic [Measures] First'” (“人民至上”不是“防疫至上“).

The phrase “the people first” (人民至上 rénmín zhìshàng), also “putting the people in the first place,” is an important part of the Party’s ‘people-based, people-oriented’ governing concept. The phrase became especially relevant as part of Xi Jinping’s now-famous “put people and their life first” slogan (人民至上,生命至上, rénmín zhìshàng, shēngmìng zhìshàng), which became one of the most important official phrases of 2020 in light of the fight against Covid19.

The Zhejiang article starts by addressing the recent unrest surrounding China’s zero Covid policy, writing:

Since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus epidemic in late 2019, already three years have passed. As the time of preventing and controlling the epidemic situation is getting stretched, many people’s psychological tolerance and endurance level are put to the test, and they are even breaking down little by little. As some netizens say: if the first year was about panic followed by the secret joy of being able to have a good rest at home; the second year began to be more bewildering and was about the hope for a quick end to the epidemic situation; the third year is then more about dissatisfaction, when will this finally end?”

The article mentioned that in addition to growing frustrations about the endless pandemic, various places across China have been intensifying their anti-epidemic efforts in the wrong ways:

“”(..) they are abusing their power, and are making things difficult for the people. This has led to epidemic prevention becoming deformed. They will not explicitly say they are locking down, but they are locking down, they are ignoring the interests of the masses and the demands of the people, interrupting the order of normal life at their will, and are even disregarding the lives and safety of the people, harming the image of the Party and the government, and breaking the hearts of the masses. There are even some people who will seize this epidemic situation to make money. Compared to the epidemic, it’s these phenomena which are hurting people. The ensuing sense of helplessness and tiredness and anger are all understandable.”

The article then stresses:

“Anti-epidemic measures are to guard against the virus, not to guard against the people; it was always [supposed to be] about ‘people first,’ not about so-called ‘epidemic prevention’ first. Regardless what kind of prevention and control measures are taken, they should all be aimed at letting society return to normal as soon as possible and getting life back on track as soon as possible. They are all are like “bridges” and “boats” to reach this goal, and are not meant to keep people in place, as blind and rash actions that disregard the costs.”

Zhejiang Daily mentions how the World Cup in Qatar has made some people wonder about the crowds in the audience not wearing any masks, as if there was no pandemic at all. If they can, why can’t China?

As the foremost reason, the article mentions the relatively low number of hospital beds in China.

Whereas countries such as South Korea or Japan, which are still seeing high numbers of new Covid infections, have about 12.6 beds per 1000 people (12.65 and 12.63 respectively), China only has 6.7.

With the United States being mentioned as an example of a country where Covid-19 patients were using up 32.7% of total nationwide ICU capacity early in 2022, with 7 ICU beds per 100,000 people being occupied by Covid patients, the article suggests that China does not even have this many ICU beds per 100,000 people.

Zhejiang Daily posted its article on Weibo, where one related hashtag received over 350 million views by Tuesday night.

The article further mentions how China, which is a rapidly ageing country, has a relatively large elderly population. With mortality rates being higher in Covid patients over the age of 60, it is estimated that if China would let go of its Covid measures, some 600,000 seniors (60+) catching the virus would die (the article bases this estimation on mortality rates in the Singaporean Covid epidemic.)

Due to Chinese historical, social and traditional values, the protection of the country’s eldest is of great importance. Zhejiang Daily suggests that this is different from Western societies: “Some Western countries had nursing homes where hundreds of people passed away during the epidemic – if that would happen in China, it would be unacceptable. If you understand this point, you can also understand all the efforts we are putting out to contain the epidemic situation.”

And so, Zhejiang Daily highlights the high price people in many Western countries paid to get to the stage in the epidemic where they are today.

The article repeats some of the arguments that have previously also been included in writings in other newspapers and by political commentator Hu Xijin, namely that with China’s current zero-Covid policy and the adjustments that were recently made, the country is now focusing on precise and science-backed epidemic prevention that is meant to put as little strain as possible on society and economy.

However, the latest changes and the essence of China’s zero Covid policy are not properly implemented everywhere, the article says, as there is a lack of understanding or an incapability to handle the situation due to a local lack of staff or available methods. Then there is also the issue of some people making money off of to strict epidemic measures. This has all led to tragic situations that should never have happened.

Although the article does not mention any concrete examples, there are many recent incidents where people did not get the help they needed because of excessive Covid measures. We have covered some of the biggest ones on What’s on Weibo, including the young girl who passed away after getting gravely ill at a quarantine location in Ruzhou; the toddler who died due to carbon monoxide poisoning and a severe delay in medical help in Lanzhou; and the woman who jumped from the 12th floor of an apartment building in Hohhot, although her daughters had been seeking requesting help for her deteriorating mental state for hours.

The problem at hand, Zhejiang Daily suggests, is that some local authorities are putting epidemic prevention first instead of putting people’s lives first. The problem can also not be solved by letting go of all measures, nor by adhering to a ‘one-size-fits-all’ zero Covid policy (“走出疫情阴霾,不是一句“放”与“不放”就能解决的事情.”)

Instead of fighting for ‘opening up’ versus ‘closing down’, the point is to find a “soft landing” (“软着陆”) way out the “haze of the epidemic situation” (“走出疫情阴霾”).

Although the article does not give very concrete answers on what the best way forward is – although it does mention increasing China’s vaccination rates, hospital beds, and available medications, – it proposes to look at the exact pain points within the bigger picture, and to deal with them one by one in order to quickly improve epidemic situations across the country.

At the same time, it also advocates that the various systems that are in place across China should be efficiently unified. The health code system in China is not operated nationally, and instead, various regions are each working with their own Health Code apps (see this article).

So, in other words: local problems should be spotlighted and dealt with, while regional innovative tools or effective measures should also be pinpointed and standardized across the country (“一地创新、全国使用”).

The article does not explicitly mention the recent unrest across China, but it does hint at it: “The voices and the demands of the people have always been the central point regarding the adjustment and optimization of anti-epidemic policies. There is only one goal in the fight against the virus, and that is to benefit the people, to protect the health and safety of every person. If we hold on to this point, our steps won’t be chaotic, and our actions won’t stray from the intended line.”

On Weibo and WeChat, the article is discussed by many netizens (#浙江宣传发文人民至上不是防疫至上#). One hashtag related to the article received over 350 million views on Weibo on Tuesday (#人民至上不是防疫至上#).

Many people spoke out in support of the article.

“This is a well-written article. It really combines the two components of ‘what we want to say’ and ‘what the ordinary people want to hear,’ it brings in some fresh air, clears up some confusion and eases the mood,” one commenter from Hubei writes: “But why is only Zhejiang Daily publishing this? The Zhejiang Propaganda [department] is the pride on the propaganda front, the fact that there’s just one Zhejiang Propaganda [department] is the sorrow on the propaganda front.”

“Finally something that’s clear-headed,” others wrote. “This article actually moved me. There’s been masses of people raising their voice recently because some local epidemic measures are creating problems and are not benefiting the people. No matter how we solve it, the target is unchanged.”

“Well put!” others wrote: “So what do we do now?”

But not everyone was convinced that the article is meaningful. “I don’t buy it,” one person wrote: “This won’t do much more than a fart.”

“The title is welcomed by the people, the content protects the central authority,” another commenter said.

The Zhejiang Daily article suggests that there is nothing wrong with the general zero-Covid policy and the twenty new measures, but instead points at how various places across the country have different interpretations of the policies and sometimes take drastic measures which actually undermine the authority of the central government (“中央定下来的“动态清零”总方针、优化防控二十条措施,一些地方有不同解读,极大降低了中央政策的权威性.”)

“It only scratches the outside of the boot,” another Weibo user replied: “It does not talk about the main point and avoids taking responsibility by how it’s written. It shifts the conflict to ordinary people (..), the fact that we are still reading these kinds of [xxx] articles in 2022 is typical [xxx] socialism.”

Regardless of criticism, many people did praise how Zhejiang authorities wrote the article: “Zhejiang has done quite well, and I’ll praise their Publicity Department.”

Read more about the “11.24” unrest in China here.

By Manya Koetse

If you appreciate what we do, please subscribe here or support us by donating.

Featured image via Zhejiang Daily.

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China and Covid19

Sick Kids, Worried Parents, Overcrowded Hospitals: China’s Peak Flu Season on the Way

“Besides Mycoplasma infections, cases include influenza, Covid-19, Norovirus, and Adenovirus. Heading straight to the hospital could mean entering a cesspool of viruses.”

Published

8 months agoon

November 22, 2023

In the early morning of November 21, parents are already queuing up at Xi’an Children’s Hospital with their sons and daughters. It’s not even the line for a doctor’s appointment, but rather for the removal of IV needles.

The scene was captured in a recent video, only one among many videos and images that have been making their rounds on Chinese social media these days (#凌晨的儿童医院拔针也要排队#).

One photo shows a bulletin board at a local hospital warning parents that over 700 patients are waiting in line, estimating a waiting time of more than 13 hours to see a doctor.

Another image shows children doing their homework while hooked up on an IV.

Recent discussions on Chinese social media platforms have highlighted a notable surge in flu cases. The ongoing flu season is particularly impacting children, with multiple viruses concurrently circulating and contributing to a high incidence of respiratory infections.

Among the prevalent respiratory infections affecting children are Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections, influenza, and Adenovirus infection.

The spike in flu cases has resulted in overcrowded children’s hospitals in Beijing and other Chinese cities. Parents sometimes have to wait in line for hours to get an appointment or pick up medication.

According to one reporter at Haibao News (海报新闻), there were so many patients at the Children’s Hospital of Capital Institute of Pediatrics (首都儿科研究所) on November 21st that the outpatient desk stopped accepting new patients by the afternoon. Meanwhile, 628 people were waiting in line to see a doctor at the emergency department.

Reflecting on the past few years, the current flu season marks China’s first ‘normal’ flu peak season since the outbreak of Covid-19 in late 2019 / early 2020 and the end of its stringent zero-Covid policies in December 2022. Compared to many other countries, wearing masks was also commonplace for much longer following the relaxation of Covid policies.

Hu Xijin, the well-known political commentator, noted on Weibo that this year’s flu season seems to be far worse than that of the years before. He also shared that his own granddaughter was suffering from a 40 degrees fever.

“We’re all running a fever in our home. But I didn’t dare to go to the hospital today, although I want my child to go to the hospital tomorrow. I heard waiting times are up to five hours now,” one Weibo user wrote.

“Half of the kids in my child’s class are sick now. The hospital is overflowing with people,” another person commented.

One mother described how her 7-year-old child had been running a fever for eight days already. Seeking medical attention on the first day, the initial diagnosis was a cold. As the fever persisted, daily visits to the hospital ensued, involving multiple hours for IV fluid administration.

While this account stems from a single Weibo post within a fever-advice community, it highlights a broader trend: many parents swiftly resort to hospital visits at the first signs of flu or fever. Several factors contribute to this, including a lack of General Practitioners in China, making hospitals the primary choice for medical consultations also in non-urgent cases.

There is also a strong belief in the efficacy of IV infusion therapy, whether fluid-based or containing medication, as the quickest path to recovery. Multiple factors contribute to the widespread and sometimes irrational use of IV infusions in China. Some clinics are profit-driven and see IV infusions as a way to make more money. Widespread expectations among Chinese patients that IV infusions will make them feel better also play a role, along with some physicians’ lacking knowledge of IV therapy or their uncertainty to distinguish bacterial from viral infections (read more here)

To prevent an overwhelming influx of patients to hospitals, Chinese state media, citing specialists, advise parents to seek medical attention at the hospital only for sick infants under three months old displaying clear signs of fever (with or without cough). For older children, it is recommended to consult a doctor if a high fever persists for 3 to 5 days or if there is a deterioration in respiratory symptoms. Children dealing with fever and (mild) respiratory symptoms can otherwise recover at home.

One Weibo blogger (@奶霸知道) warned parents that taking their child straight to the hospital on the first day of them getting sick could actually be a bad idea. They write:

“(..) pediatric departments are already packed with patients, and it’s not just Mycoplasma infections anymore. Cases include influenza, Covid-19, Norovirus, and Adenovirus. And then, of course, those with bad luck are cross-infected with multiple viruses at the same time, leading to endless cycles. Therefore, if your child experiences mild coughing or a slight fever, consider observing at home first. Heading straight to the hospital could mean entering a cesspool of viruses.”

The hashtag for “fever” saw over 350 million clicks on Weibo within one day on November 22.

Meanwhile, there are also other ongoing discussions on Weibo surrounding the current flu season. One topic revolves around whether children should continue doing their homework while receiving IV fluids in the hospital. Some hospitals have designated special desks and study areas for children.

Although some commenters commend the hospitals for being so considerate, others also remind the parents not to pressure their kids too much and to let them rest when they are not feeling well.

Opinions vary: although some on Chinese social media say it's very thoughtful for hospitals to set up areas where kids can study and read, others blame parents for pressuring their kids to do homework at the hospital instead of resting when not feeling well. pic.twitter.com/gnQD9tFW2c

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) November 22, 2023

By Manya Koetse, with contributions from Miranda Barnes

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China and Covid19

Repurposing China’s Abandoned Nucleic Acid Booths: 10 Innovative Transformations

Abandoned nucleic acid booths are getting a second life through these new initiatives.

Published

1 year agoon

May 19, 2023

During the pandemic, nucleic acid testing booths in Chinese cities were primarily focused on maintaining physical distance. Now, empty booths are being repurposed to bring people together, serving as new spaces to serve the community and promote social engagement.

Just months ago, nucleic acid testing booths were the most lively spots of some Chinese cities. During the 2022 Shanghai summer, for example, there were massive queues in front of the city’s nucleic acid booths, as people needed a negative PCR test no older than 72 hours for accessing public transport, going to work, or visiting markets and malls.

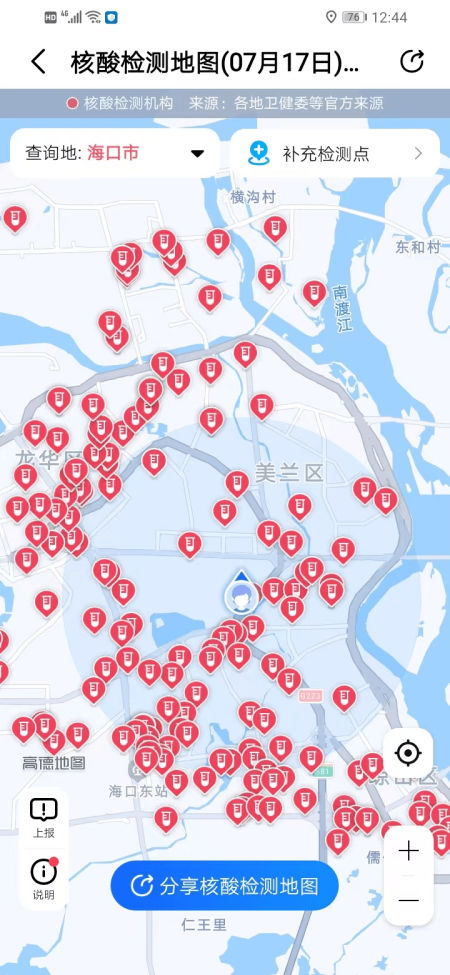

The word ‘hésuān tíng‘ (核酸亭), nucleic acid booth (also:核酸采样小屋), became a part of China’s pandemic lexicon, just like hésuān dìtú (核酸地图), the nucleic acid test map lauched in May 2022 that would show where you can get a nucleic test.

Example of nucleic acid test map.

During Halloween parties in Shanghai in 2022, some people even came dressed up as nucleic test booths – although local authorities could not appreciate the creative costume.

Halloween 2022: dressed up as nucliec acid booths. Via @manyapan twitter.

In December 2022, along with the announced changed rules in China’s ‘zero Covid’ approach, nucleic acid booths were suddenly left dismantled and empty.

With many cities spending millions to set up these booths in central locations, the question soon arose: what should they do with the abandoned booths?

This question also relates to who actually owns them, since the ownership is mixed. Some booths were purchased by authorities, others were bought by companies, and there are also local communities owning their own testing booths. Depending on the contracts and legal implications, not all booths are able to get a new function or be removed yet (Worker’s Daily).

In Tianjin, a total of 266 nucleic acid booths located in Jinghai District were listed for public acquisition earlier this month, and they were acquired for 4.78 million yuan (US$683.300) by a local food and beverage company which will transform the booths into convenience service points, selling snacks or providing other services.

Tianjin is not the only city where old nucleic acid testing booths are being repurposed. While some booths have been discarded, some companies and/or local governments – in cooperation with local communities – have demonstrated creativity by transforming the booths into new landmarks. Since the start of 2023, different cities and districts across China have already begun to repurpose testing booths. Here, we will explore ten different way in which China’s abandoned nucleic test booths get a second chance at a meaningful existence.

1: Pharmacy/Medical Booths

Via ‘copyquan’ republished on Sohu.

Blogger ‘copyquan’ recently explored various ways in which abandoned PCR testing points are being repurposed.

One way in which they are used is as small pharmacies or as medical service points for local residents (居民医疗点). Alleviating the strain on hospitals and pharmacies, this was one of the earliest ways in which the booths were repurposed back in December of 2022 and January of 2023.

Chongqing, Tianjin, and Suzhou were among earlier cities where some testing booths were transformed into convenient medical facilities.

2: Market Stalls

In Suzhou, Jiangsu province, the local government transformed vacant nucleic acid booths into market stalls for the Spring Festival in January 2022, offering them free of charge to businesses to sell local products, snacks, and traditional New Year goods.

The idea was not just meant as a way for small businesses to conveniently sell to local residents, it was also meant as a way to attract more shoppers and promote other businesses in the neighborhood.

3: Community Service Center

Small grid community center in Shizhuang Village, image via Sohu.

Some residential areas have transformed their local nucleic acid testing booths into community service centers, offering all kinds of convenient services to neighborhood residents.

These little station are called wǎnggé yìzhàn (网格驿站) or “grid service stations,” and they can serve as small community centers where residents can get various kinds of care and support.

4: “Refuel” Stations

In February of this year, 100 idle nucleic acid sampling booths were transformed into so-called “Rider Refuel Stations” (骑士加油站) in Zhejiang’s Pinghu. Although it initially sounds like a place where delivery riders can fill up their fuel tanks, it is actually meant as a place where they themselves can recharge.

Delivery riders and other outdoor workers can come to the ‘refuel’ station to drink some water or tea, warm their hands, warm up some food and take a quick nap.

5: Free Libraries

image via sohu.

In various Chinese cities, abandoned nucleic acid booths have been transformed into little free libraries where people can grab some books to read, donate or return other books, and sit down for some reading.

Changzhou is one of the places where you’ll find such “drifting bookstores” (漂流书屋) (see video), but similar initiatives have also been launched in other places, including Suzhou.

6: Study Space

Photos via Copyquan’s article on Sohu.

Another innovative way in which old testing points are being repurposed is by turning them into places where students can sit together to study. The so-called “Let’s Study Space” (一间习吧), fully airconditioned, are opened from 8 in the morning until 22:00 at night.

Students – or any citizens who would like a nice place to study – can make online reservations with their ID cards and scan a QR code to enter the study rooms.

There are currently ten study booths in Anji, and the popular project is an initiative by the Anji County Library in Zhejiang (see video).

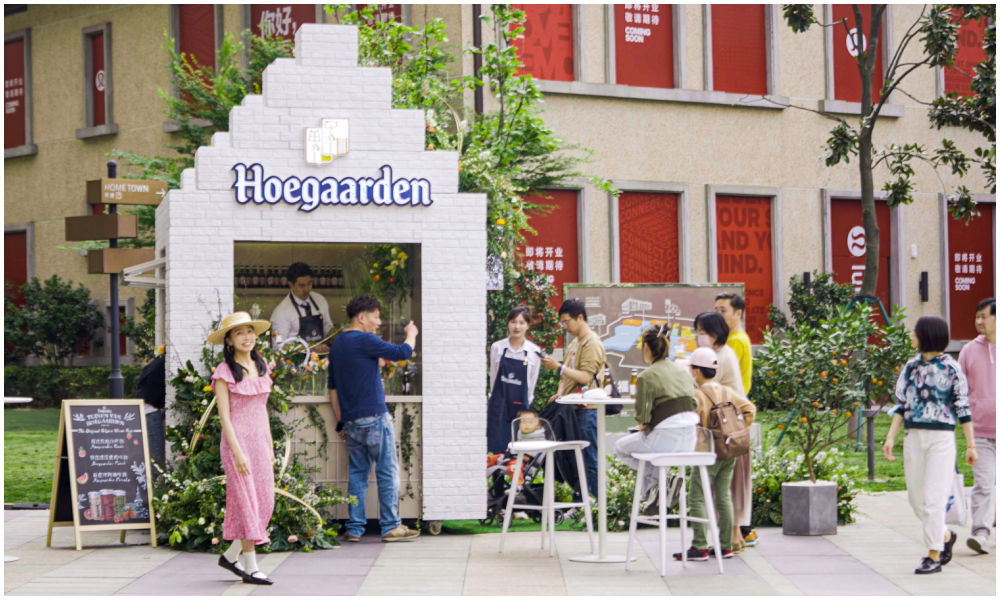

7: Beer Kiosk

Hoegaarden beer shop, image via Creative Adquan.

Changing an old nucleic acid testing booth into a beer bar is a marketing initiative by the Shanghai McCann ad agency for the Belgium beer brand Hoegaarden.

The idea behind the bar is to celebrate a new spring after the pandemic. The ad agency has revamped a total of six formr nucleic acid booths into small Hoegaarden ‘beer gardens.’

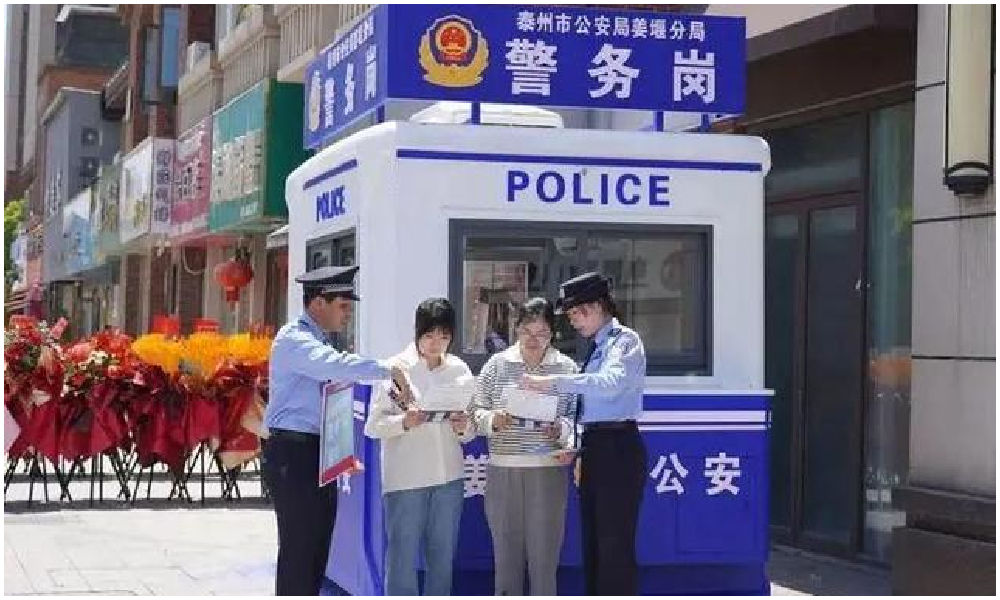

8: Police Box

In Taizhou City, Jiangsu Province, authorities have repurposed old testing booths and transformed them into ‘police boxes’ (警务岗亭) to enhance security and improve the visibility of city police among the public.

Currently, a total of eight vacant nucleic acid booths have been renovated into modern police stations, serving as key points for police presence and interaction with the community.

9: Lottery Ticket Booths

Image via The Paper

Some nucleic acid booths have now been turned into small shops selling lottery tickets for the China Welfare Lottery. One such place turning the kiosks into lottery shops is Songjiang in Shanghai.

Using the booths like this is a win-win situation: they are placed in central locations so it is more convenient for locals to get their lottery tickets, and on the other hand, the sales also help the community, as the profits are used for welfare projects, including care for the elderly.

10: Mini Fire Stations

Micro fire stations, images via ZjNews.

Some communities decided that it would be useful to repurpose the testing points and turn them into mini fire kiosks, just allowing enough space for the necessary equipment to quickly respond to fire emergencies.

Want to read more about the end of ‘zero Covid’ in China? Check our other articles here.

By Manya Koetse,

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?