China Fashion & Beauty

Fashion that Hurts? Online Debates on China’s Draft Law Regarding ‘Harmful’ Clothes

The proposed ban on clothing deemed harmful is stirring debate, with some arguing for the significance of protecting national pride and others emphasizing the value of personal expression.

Published

11 months agoon

China’s recent proposal to ban clothing that “hurts national feelings” has triggered social media debates about freedom of dress and cultural sensitivities. The controversial amendment has raised questions about who decides what’s offensive for which reason.

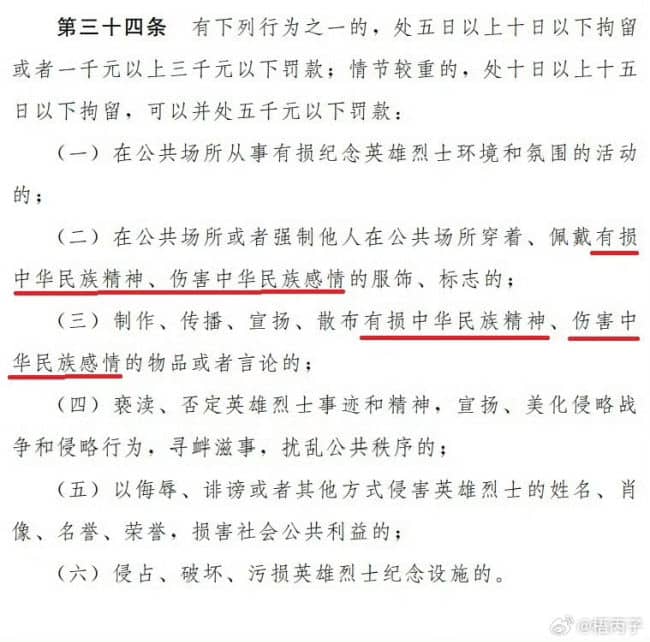

A draft amendment to China’s Public Security Administration Punishments Law (治安管理处罚法) has caused some controversy this week for proposing a ban on clothes that “hurt national feelings.”

The discussions are about Article 34, clausules 3 and 4, which point out that wearing clothing or symbols that are deemed “harmful” to “the spirit and feelings of the Chinese nation” could become illegal. Offenders may face up to 15 days of detention and a fine of 5,000 yuan ($680).

The revised Article is part of a section about acts disrupting public order and their punishment, mentioning the protection of China’s heroes and martyrs.

Especially over the past three to four years, Chinese authorities have placed more importance on protecting the image of China’s “heroes and martyrs.” In 2018, the Heroes and Martyrs Protection Law was adopted to strengthen the protection of those who have made significant contributions to the nation and sacrificed their lives in the process.

Those insulting the PLA can face serious consequences. In 2021, former Economic Observer journalist Qiu Ziming (仇子明), along with two other bloggers, were the first persons to be charged under the new law as they were detained for “insulting” Chinese soldiers. Qiu, who had 2.4 million fans on his Weibo page, made remarks questioning the number of casualties China said it suffered in the India border clash. He was sentenced to eight months in prison.

Earlier this year, Chinese comedian Li Haoshi was canceled making a joke that indirectly made a comparison between PLA soldiers and stray dogs, while also placing words famously used by Xi Jinping in a ridiculous context.

Screenshot of the draft widely shared on social media.

The draft is open for public comment through September 30, and it is therefore just a draft of a proposed amendment at this point.

Nevertheless, it has ignited many discussions on Chinese social media, where legal experts, bloggers, and regular netizens gave their views on the issue, with many people opposing the amendment.

This a translation of the first four clausules of Article 34 by Jeremy Daum’s China Law Translate (see the full translation here). Note that the discussions are focused on the item (2) and (3) revisions:

“Article 34:Those who commit any of the following acts are to be detained for between 5 and 10 days or be fined between 1,000 and 3,000 RMB; and where the circumstances are more serious, they are to be detained for between 10 and 15 days and may be concurrently fined up to 5,000 RMB:

(1) engaging in activities in public places that are detrimental to the environment and atmosphere for commemorating heroes and martyrs;

(2) Wearing clothing or bearing symbols in public places that are detrimental to the spirit of the Chinese people and hurt the feelings of the Chinese people, or forcing others do do so;

(3) Producing, transmitting, promoting, or disseminating items or speech that is detrimental to the spirit of the Chinese people and hurts the feelings of the Chinese people;

(4) Desecrating or negating the deeds and spirit of heroes and martyrs, or advocating or glorifying wars of aggression or aggressive conduct, provocation, or disrupting public order.”

Here, we mention the biggest online discussions surounding the draft amendment.

Main Objections to the Amendment

On Chinese social media site Weibo, commenters used various hashtags to discuss the recent draft, including the hashtags “China’s Proposed Amendment to the Public Security Administration Punishments Law” (#我国拟修订治安管理处罚法#), “Article 34 of the Draft Amendment to the Public Security Administration Punishments Law” (#治安管理处罚法修订草案第34条#) or “Harm the Feelings of the Chinese Nation” (#伤害中华民族感情#).

The issue that people are most concerned about is the vague definition “harming or hurting the spirit and feelings of the Chinese nation” (“伤害中华民族精神、感情”).

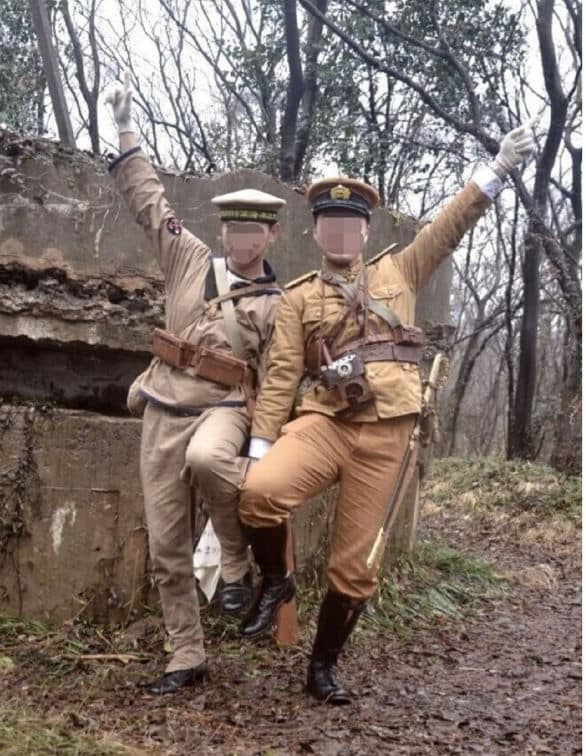

Although Chinese state media outlets, including the English-language Global Times, indicate that the clause is deemed to target some provocative actions to attract public attention, such as wearing Japanese military uniforms at sensitive sites, legal experts and social media users are expressing apprehensions regarding its ambiguity.

Questions arise: Who determines what qualifies as “harmful”? What criteria will be used? How will it be enforced? Beyond concerns about the absence of clear guidelines on which attire might be deemed illegal and for what reasons, there are fears of potential misinterpretation and misuse of such a law due to its subjective nature.

Some people question whether wearing foreign brands like Adidas or Nike could be considered offensive. There are also concerns about whether wearing sports attire supporting specific clubs might be seen as disrespectful. Another common topic is cosplay, a popular form of role-playing among China’s youth, where individuals dress up in costumes and accessories to portray specific characters. Can people still dress up in the way they like?

Well-known political commentator Hu Xijin published a video commentary about the issue on September 7, suggesting that the law in question could be more concrete and avoid misunderstanding by explicitly mentioning it targets facism, racism, or separatism. He also suggested that it is important for China’s legal system to provide people with a sense of security (– rather than scaring them).

Others reiterated similar views. If the clausules are indeed specifically about slandering national heroes and martyrs, which makes sense considering their context, they should be rephrased. One popular legal blogger (@皇城根下刀笔吏) wrote:

“The legal enforceability of harming the spirit and the feelings of the Chinese nation is not quite the same as insulting or slandering heroes. Because it is actually very clear who our national heroes are. They are classified as martyrs and were approved by the state, it’s very clear. But when it comes to the feelings and the spirit of the Chinese nation, this is just very vague (..) And ambiguity brings about a mismatch in the practice of implementation, which will make people lose trust in this legal provision and makes them feel unsafe.”

Although a majority of commenters agree that the proposed amendment is vague, some also express that they would support a ban on clothes that are especially offensive. Among them is the popular blogger Han Dongyan (@韩东言), who has over 2.3 million followers on Weibo.

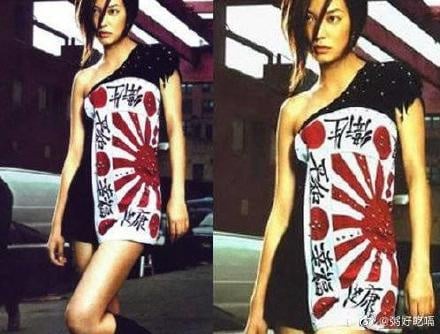

One example that is mentioned a lot, also by Han, is the 2001 controversy surrounding Chinese actress Vicky Zhao who wore a mini-dress printed with the old Japanese naval flag during a fashion shoot, triggering major backlash over her perceived lack of sensitivity to historical matters and the offensive dress.

Han also mentioned a 2018 example of two young men dressed in Imperial Japanese military uniforms taking a photo in front of the Shaojiashan Bunker at Zijin Mountain, where the Second Sino-Japanese War is commemmorated.

Kimono Problems

One trending story that is very much entangled with recent discussions about the proposed ban on ‘harmful’ clothing is that about a group of Chinese men and women who were recently denied access to the Panlongcheng National Archaeological Site Park in Wuhan because staff members allegedly mistook their clothing for Japanese traditional attire.

The individuals were actually not wearing Japanese traditional dress at all; they were wearing traditional Tang dynasty clothing to take photos of themselves. This is part of the Hanfu Movement, a social trend that is popular among younger people who supports the wearing of Han Chinese ethnic clothing (read more).

Amid discussions over draft law banning clothes harmful to the "spirit, feelings of the Chinese nation," this incident sparked discussions: Chinese wearing Tang clothes were denied entry at Panlongcheng Park, Wuhan, after local guard mistook their clothes for Japanese attire. pic.twitter.com/IokazvhBhl

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) September 8, 2023

According to Zhengguan News (正观新闻), there is no official park policy prohibiting the wearing of Japanese clothing, and an internal investigation into the incident is ongoing. The Paper reported that the incident allegedly happened around closing time.

Meanwhile, this incident has sparked discussions because it highlights the potential consequences when authorities arbitrarily enforce clothing rules and misinterpret situations. One netizen wrote: “It illustrates that when “some members of the public” cannot even tell the difference between Hanfu, Tang dynasty attire, and Japanese kimono, they are simply venting their emotions.”

Last year, a Chinese female cosplayer who was dressed in a Japanese summer kimono while taking pictures in Suzhou’s ‘Little Tokyo’ area was taken away by local police for ‘provoking trouble’ (read here).

A young Chinese woman was taken away by local police in Suzhou last Wednesday because she was wearing a kimono. "If you would be wearing Hanfu (Chinese traditional clothing), I never would have said this, but you are wearing a kimono, as a Chinese. You are Chinese!" pic.twitter.com/et8vWOferQ

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) August 15, 2022

A video showed how the young woman was scolded by an officer for wearing the Japanese kimono, suggesting she is not allowed to do so as a Chinese person. The girl was known to be a cosplayer, and she was dressed up as the character Ushio Kofune from the Japanese manga series Summer Time Rendering, wearing a cotton summer kimono, better known as yukata.

The incident sparked extensive debates, with differing viewpoints emerging. While some believed the girl’s choice of wearing Japanese clothing during the week leading up to August 15, a memorial day marking the end of the war, was insensitive, many commenters defended her right to engage in cosplay.

These discussions are resurfacing on Weibo, underscoring the divided opinions on the matter.

One Weibo user expressed a common viewpoint: “I believe wearing a Japanese kimono in everyday situations is not a problem, but doing so at specific times and places could potentially offend the sentiments of the Chinese nation.” Another blogger (@猹斯拉) also voiced support for a law that could prohibit certain clothing: “If you genuinely believe what you’re wearing is not harmful, you always have the right to make your argument.”

However, there is also significant opposition, with some individuals posting images of themselves reading George Orwell’s 1984 at night or making cynical remarks like, “Maybe we should say nothing and wear nothing, as anything else could lead to our arrest.”

“This is not progress,” another person wrote: “It’s taking another step back in time.”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

With contributions by Miranda Barnes

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Chinese Sun Protection Fashion: Move over Facekini, Here’s the Peek-a-Boo Polo

From facekini to no-face hoodie: China’s anti-tan fashion continues to evolve.

Published

2 months agoon

June 6, 2024

It has been ten years since the Chinese “facekini”—a head garment worn by Chinese ‘aunties’ at the beach or swimming pool to prevent sunburn—went international.

Although the facekini’s debut in French fashion magazines did not lead to an international craze, it did turn the term “facekini” (脸基尼), coined in 2012, into an internationally recognized word.

The facekini went viral in 2014.

In recent years, China has seen a rise in anti-tan, sun-protection garments. More than just preventing sunburn, these garments aim to prevent any tanning at all, helping Chinese women—and some men—maintain as pale a complexion as possible, as fair skin is deemed aesthetically ideal.

As temperatures are soaring across China, online fashion stores on Taobao and other platforms are offering all kinds of fashion solutions to prevent the skin, mainly the face, from being exposed to the sun.

One of these solutions is the reversed no-face sun protection hoodie, or the ‘peek-a-boo polo,’ a dress shirt with a reverse hoodie featuring eye holes and a zipper for the mouth area.

This sun-protective garment is available in various sizes and models, with some inspired by or made by the Japanese NOTHOMME brand. These garments can be worn in two ways—hoodie front or hoodie back. Prices range from 100 to 280 yuan ($13-$38) per shirt/jacket.

The no-face hoodie sun protection shirt is sold in various colors and variations on Chinese e-commerce sites.

Some shops on Taobao joke about the extreme sun-protective fashion, writing: “During the day, you don’t know which one is your wife. At night they’ll return to normal and you’ll see it’s your wife.”

On Xiaohongshu, fashion commenters note how Chinese sun protective clothing has become more extreme over the past few years, with “sunburn protection warriors” (防晒战士) thinking of all kinds of solutions to avoid a tan.

Although there are many jokes surrounding China’s “sun protection warriors,” some people believe they are taking it too far, even comparing them to Muslim women dressed in burqas.

Image shared on Weibo by @TA们叫我董小姐, comparing pretty girls before (left) and nowadays (right), also labeled “sunscreen terrorists.”

Some Xiaohongshu influencers argue that instead of wrapping themselves up like mummies, people should pay more attention to the UV index, suggesting that applying sunscreen and using a parasol or hat usually offers enough protection.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy.

Published

3 months agoon

May 3, 2024

It seemed like such a good idea. For this year’s World Book Day, Chinese tea brand LELECHA (乐乐茶) put a spotlight on Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881-1936), one of the most celebrated Chinese authors the 20th century and turned him into the the ‘brand ambassador’ of their special new “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙) milk tea.

LELECHA is a Chinese chain specializing in new-style tea beverages, including bubble tea and fruit tea. It debuted in Shanghai in 2016, and since then, it has expanded rapidly, opening dozens of new stores not only in Shanghai but also in other major cities across China.

Starting on April 23, not only did the LELECHA ‘Smoky Oolong” paper cups feature Lu Xun’s portrait, but also other promotional materials by LELECHA, such as menus and paper bags, accompanied by the slogan: “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” (“老烟腔,新青年”). The marketing campaign was a joint collaboration between LELECHA and publishing house Yilin Press.

Lu Xun featured on LELECHA products, image via Netease.

The slogan “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” is a play on the Chinese magazine ‘New Youth’ or ‘La Jeunesse’ (新青年), the influential literary magazine in which Lu’s famous short story, “Diary of a Madman,” was published in 1918.

The design of the tea featuring Lu Xun’s image, its colors, and painting style also pay homage to the era in which Lu Xun rose to prominence.

Lu Xun (pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a leading figure within China’s May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1915-24) is also referred to as the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance. It was the cultural revolution brought about by the political demonstrations on the fourth of May 1919 when citizens and students in Beijing paraded the streets to protest decisions made at the post-World War I Versailles Conference and called for the destruction of traditional culture[1].

In this historical context, Lu Xun emerged as a significant cultural figure, renowned for his critical and enlightened perspectives on Chinese society.

To this day, Lu Xun remains a highly respected figure. In the post-Mao era, some critics felt that Lu Xun was actually revered a bit too much, and called for efforts to ‘demystify’ him. In 1979, for example, writer Mao Dun called for a halt to the movement to turn Lu Xun into “a god-like figure”[2].

Perhaps LELECHA’s marketing team figured they could not go wrong by creating a milk tea product around China’s beloved Lu Xun. But for various reasons, the marketing campaign backfired, landing LELECHA in hot water. The topic went trending on Chinese social media, where many criticized the tea company.

Commodification of ‘Marxist’ Lu Xun

The first issue with LELECHA’s Lu Xun campaign is a legal one. It seems the tea chain used Lu Xun’s portrait without permission. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s great-grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation, quickly demanded an end to the unauthorized use of Lu Xun’s image on tea cups and other merchandise. He even hired a law firm to take legal action against the campaign.

Others noted that the image of Lu Xun that was used by LELECHA resembled a famous painting of Lu Xun by Yang Zhiguang (杨之光), potentially also infringing on Yang’s copyright.

But there are more reasons why people online are upset about the Lu Xun x LELECHA marketing campaign. One is how the use of the word “smoky” is seen as disrespectful towards Lu Xun. Lu Xun was known for his heavy smoking, which ultimately contributed to his early death.

It’s also ironic that Lu Xun, widely seen as a Marxist, is being used as a ‘brand ambassador’ for a commercial tea brand. This exploits Lu Xun’s image for profit, turning his legacy into a commodity with the ‘smoky oolong’ tea and related merchandise.

“Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you in an article. ”

On April 29, LELECHA finally issued an apology to Lu Xun’s relatives and the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation for neglecting the legal aspects of their marketing campaign. They claimed it was meant to promote reading among China’s youth. All Lu Xun materials have now been removed from LELECHA’s stores.

Statement by LELECHA.

On Chinese social media, where the hot tea became a hot potato, opinions on the issue are divided. While many netizens think it is unacceptable to infringe on Lu Xun’s portrait rights like that, there are others who appreciate the merchandise.

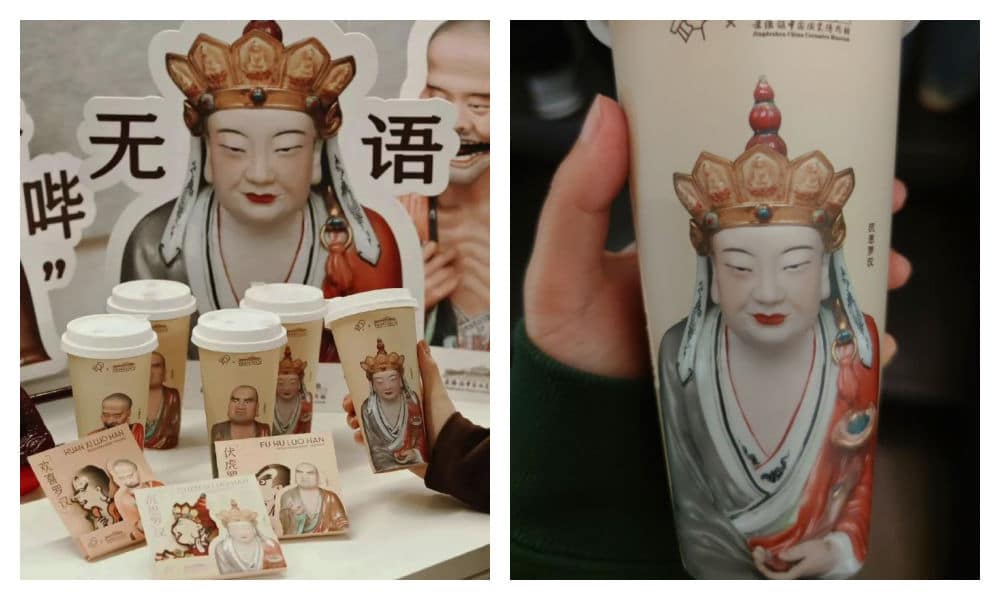

The LELECHA controversy is similar to another issue that went trending in late 2023, when the well-known Chinese tea chain HeyTea (喜茶) collaborated with the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum to release a special ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ (佛喜) latte tea series adorned with Buddha images on the cups, along with other merchandise such as stickers and magnets. The series featured three customized “Buddha’s Happiness” cups modeled on the “Speechless Bodhisattva” (无语菩萨), which soon became popular among netizens.

The HeyTea Buddha latte series, including merchandise, was pulled from shelves just three days after its launch.

However, the ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ success came to an abrupt halt when the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Shenzhen intervened, citing regulations that prohibit commercial promotion of religion. HeyTea wasted no time challenging the objections made by the Bureau and promptly removed the tea series and all related merchandise from its stores, just three days after its initial launch.

Following the Happy Buddha and Lu Xun milk tea controversies, Chinese tea brands are bound to be more careful in the future when it comes to their collaborative marketing campaigns and whether or not they’re crossing any boundaries.

Some people couldn’t care less if they don’t launch another campaign at all. One Weibo user wrote: “Every day there’s a new collaboration here, another one there, but I’d just prefer a simple cup of tea.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Schoppa, Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia UP, 159.

[2]Zhong, Xueping. 2010. “Who Is Afraid Of Lu Xun? The Politics Of ‘Debates About Lu Xun’ (鲁迅论争lu Xun Lun Zheng) And The Question Of His Legacy In Post-Revolution China.” In Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China, 257–284, 262.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?