The recent marriage announcement of the renowned Chinese calligrapher/painter Fan Zeng and Xu Meng, a Beijing TV presenter 50 years his junior, has sparked online discussions about the life and work of the esteemed Chinese artist. Some netizens think Fan lacks the integrity expected of a Chinese scholar-artist.

Recently, the marriage of a 86-year-old Chinese painter to his bride, who is half a century younger, has stirred conversations on Chinese social media.

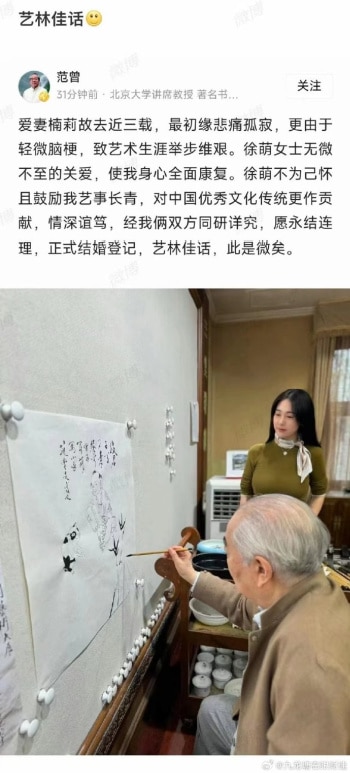

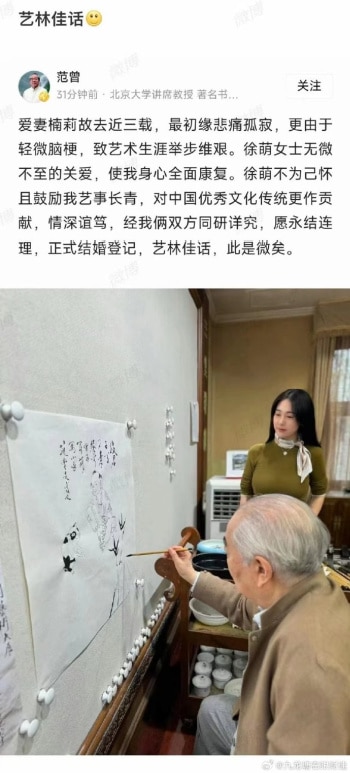

The story revolves around renowned Chinese artist, calligrapher, and scholar Fan Zeng (范曾, 1938) and his new spouse, Xu Meng (徐萌, 1988). On April 10, Fan announced their marriage through an online post accompanied by a picture.

In the picture, Fan is seen working on his announcement in calligraphic form.

Fan Zeng announces his marriage on Chinese social media.

In his writing, Zeng shares that the passing of his late wife, three years ago, left him heartbroken, and a minor stroke also hindered his work. He expresses gratitude for Xu Meng’s care, which he says led to his physical and mental recovery. Zeng concludes by expressing hope for “everlasting harmony” in their marriage.

Fan Zeng is a calligrapher and poet, but he is primarily recognized as a contemporary master of traditional Chinese painting. Growing up in a well-known literary family, his journey in art began at a young age. Fan studied under renowned mentors at the Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, including Wu Zuoren, Li Keran, Jiang Zhaohe, and Li Kuchan.

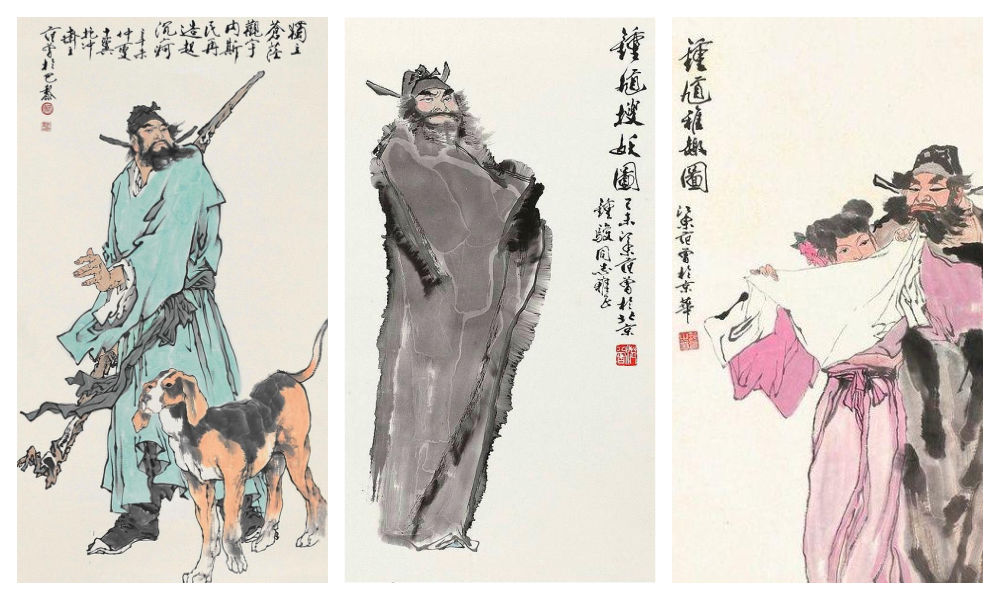

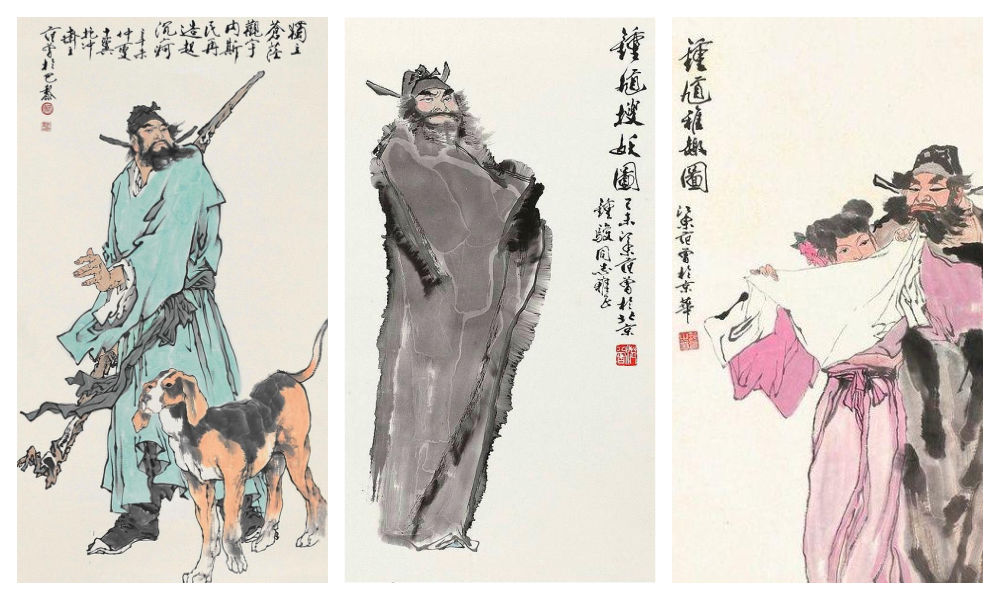

Fan gained global acclaim for his simple yet vibrant painting style. He resided in France, showcased his work in numerous exhibitions worldwide, and his pieces were auctioned at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in the 1980s.[1] One of Fan’s works, depicting spirit guardian Zhong Kui (钟馗), was sold for over 6 million yuan (828,000 USD).

Zhong Kui in works by Fan Zeng.

In his later years, Fan Zeng transitioned to academia, serving as a lecturer at Nankai University in Tianjin. At the age of 63, he assumed the role of head of the Nankai University Museum of Antiquities, as well as holding various other positions from doctoral supervisor to honorary dean.

By now, Fan’s work has already become part of China’s twentieth-century art history. Renowned contemporary scholar Qian Zhongshu once remarked that Fan “excelled all in artistic quality, painting people beyond mere physicality.”

A questionable “role model”

Fan’s third wife passed away in 2021. Later, he got to know Xu Meng, a presenter at China Traffic Broadcasting. Allegedly, shortly after they met, he gifted her a Ferrari, sparking the beginning of their relationship.

A photo of Xu and her Hermes Birkin 25 bag has also been making the rounds on social media, fueling rumors that she is only in it for the money (the bag costs more than 180,000 yuan / nearly 25,000 USD).

On Weibo, reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among netizens. Despite Fan’s reputation as a prominent philanthropist, many perceive his recent marriage as yet another instance of his lack of integrity and shamelessness.

Fan Zeng and Xu Meng. Image via Weibo.

One popular blogger (@好时代见证记录者) sarcastically wrote:

“Warm congratulations to the 86-year-old renowned contemporary erudite scholar and famous calligrapher Fan Zeng, born in 1938, on his marriage to Ms Xu Meng, a 50 years younger 175cm tall woman who is claimed to be China’s number one golden ratio beauty. Mr Fan Zeng really is a role model for us middle-aged greasy men, as it makes us feel much less uncomfortable when we’re pursuing post-90s youngsters as girlfriends and gives us an extra shield! Because if contemporary Confucian scholars [like yourself] are doing this, then we, as the inheritors of Confucian culture, can surely do the same!“

Various people criticize the fact that Xu Meng is essentially just an aide to Fan, as she can often be seen helping him during his work. One commenter wrote: “Couldn’t he have just hired an assistant? There’s no need to turn them into a bed partner.”

Others think it’s strange for a supposedly scholarly man to be so superficial: “He just wants her for her body. And she just wants him for his inheritance.”

“It’s so inappropriate,” others wrote, labeling Fan as “an old bull grazing on young grass” (lǎoniú chī nèncǎo 老牛吃嫩草).

Fan is not the only well-known Chinese scholar to ‘graze on young grass.’ The famous Chinese theoretical physicist Yang Zhenning (杨振宁, 1922), now 101 years old, also shares a 48-year age gap with his wife Weng Fen (翁帆). Fan, who is a friend of Yang’s, previously praised the love between Yang and Weng, suggesting that she kept him youthful.

Older photo posted on social media, showing Fan attending the wedding ceremony of Yang Zhenning and his 48-year-younger partner Weng Fen.

Some speculate that Fan took inspiration from Yang in marrying a significantly younger woman. Others view him as hypocritical, given his expressions of heartbreak over his previous wife’s passing, and how there’s only one true love in his lifetime, only to remarry a few years later.

Many commenters argue that Fan Zeng’s conduct doesn’t align with that of a “true Confucian scholar,” suggesting that he’s undeserving of the praise he receives.

“Mr. Wang from next door”

In online discussions surrounding Fan Zeng’s recent marriage, more reasons emerge as to why people dislike him.

Many netizens perceive him as more of a money-driven businessman rather than an idealistic artist. They label him as arrogant, critique his work, and question why his pieces sell for so much money. Some even allege that the only reason he created a calligraphy painting of his marriage announcement is to profit from it.

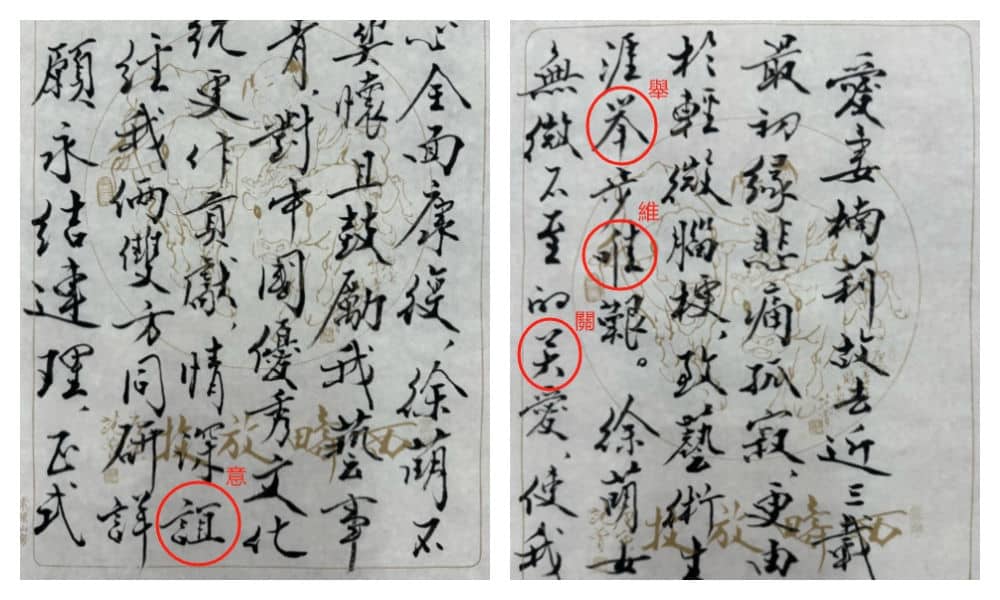

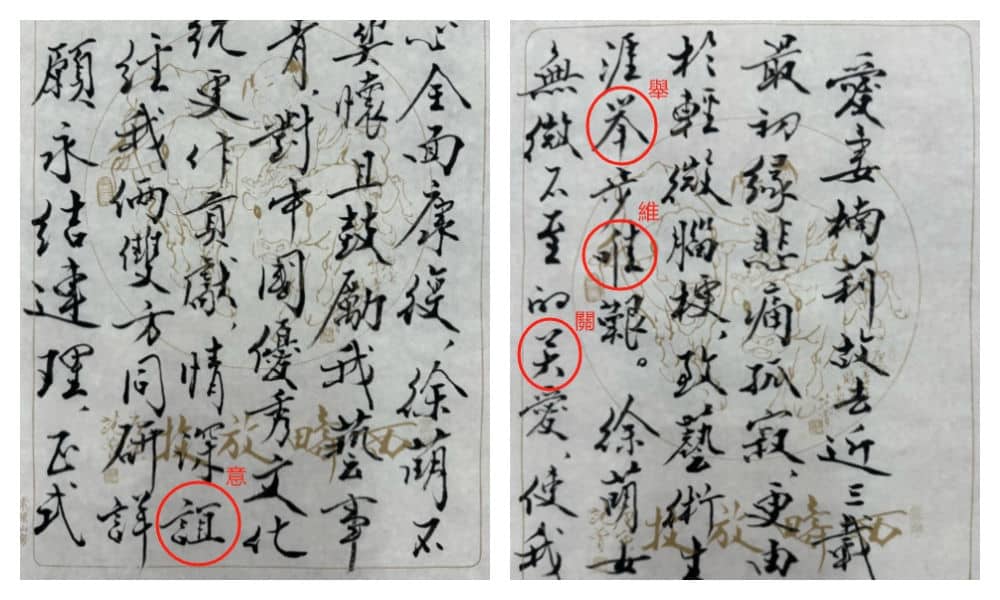

Others cast doubt on his status as a Chinese calligraphy ‘grandmaster,’ noting that his calligraphy style is not particularly impressive and may contain typos or errors. His wedding announcement calligraphy appears to blend traditional and simplified characters.

Netizens have pointed out what looks like errors or typos in Fan’s calligraphy.

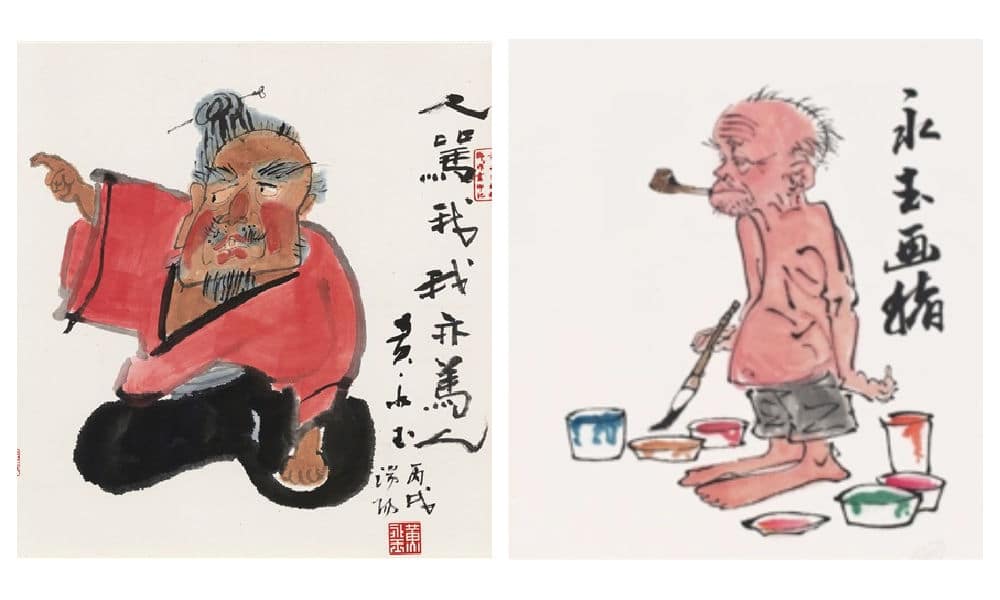

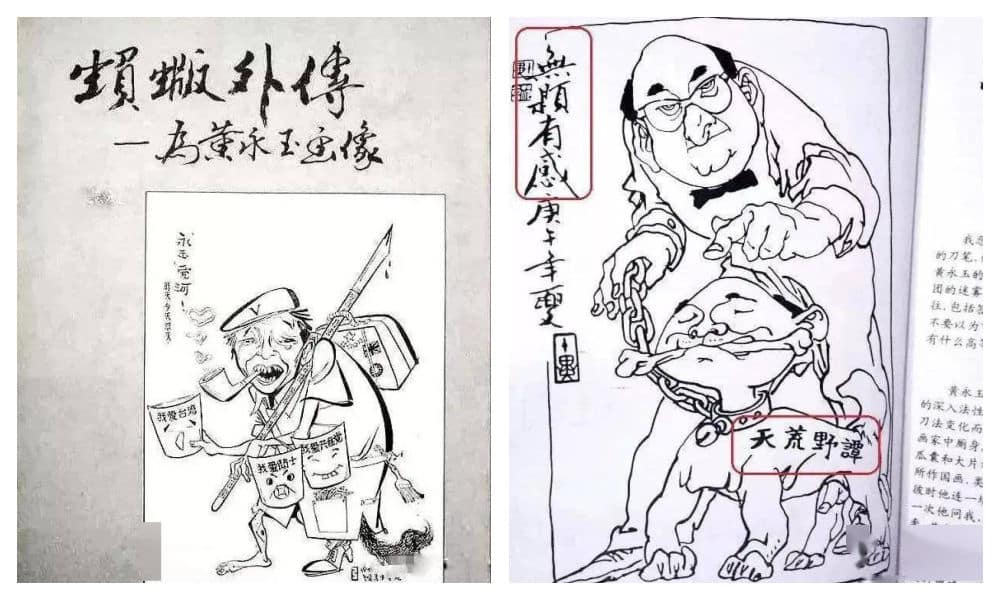

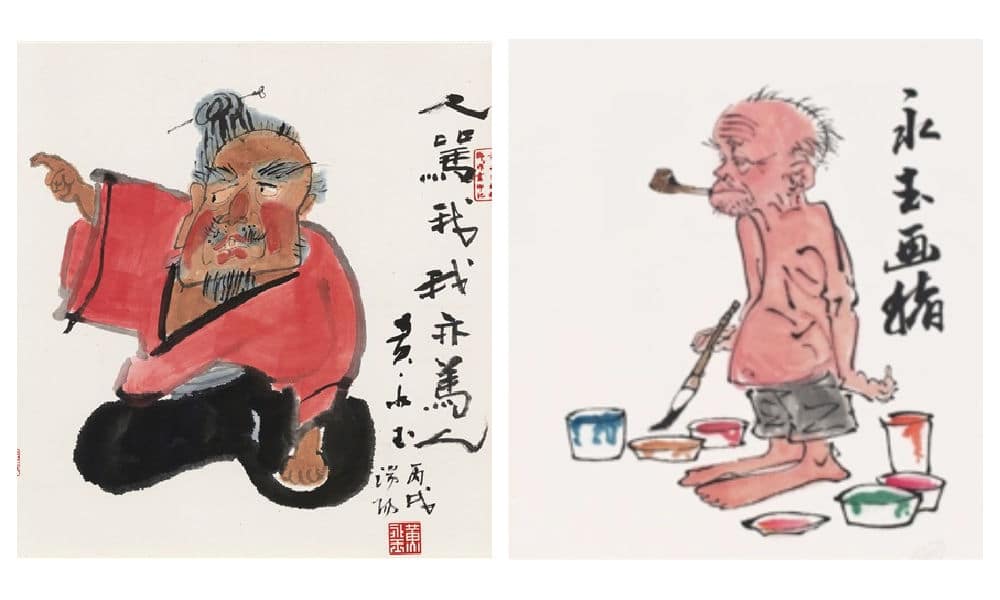

Another source of dislike stems from his history of disloyalty and his feud with another prominent Chinese painter, Huang Yongyu (黄永玉). Huang, who passed away in 2023, targeted Fan Zeng in some of his satirical paintings, including one titled “When Others Curse Me, I Also Curse Others” (“人骂我,我亦骂人”). He also painted a parrot, meant to mock Fan Zeng’s unoriginality.

Huang Yongyu made various works targeting Fan Zeng.

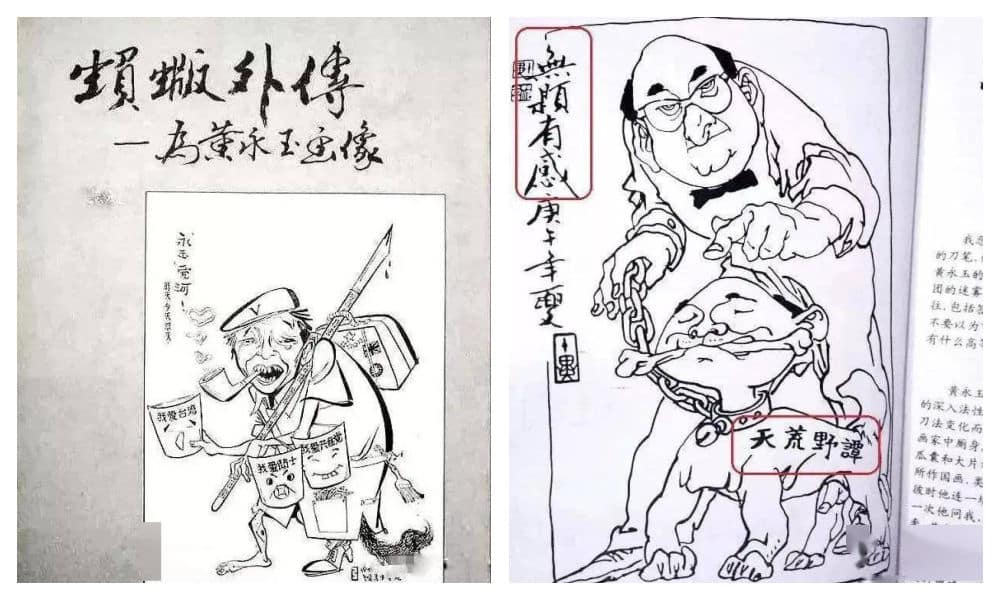

In retaliation, Fan produced his own works mocking Huang, sparking an infamous rivalry in the Chinese art world. The two allegedly almost had a physical fight when they ran into each other at the Beijing Hotel.

Fan Zeng mocked Huang Yongyu in some of his works.

Fan and Huang were once on good terms though, with Fan studying under Huang at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Through Huang, Fan was introduced to the renowned Chinese novelist Shen Congwen (沈从文, 1902-1988), Huang’s first cousin and lifelong friend. As Shen guided Fan in his studies and connected him with influential figures in China’s cultural circles, their relationship flourished.

However, during the Cultural Revolution, when Shen was accused of being a ‘reactionary,’ Fan Zeng turned against him, even going as far as creating big-character posters to criticize his former mentor.[2] This betrayal not only severed the bond between Shen and Fan but also ended Fan’s friendship with Huang, and it is still remembered by people today.

Fan Zeng’s behavior towards another former mentor, the renowned painter Li Kuchan (李苦禪, 1899-1983), was also controversial. Once Fan gained fame, he made it clear that he no longer respected Li as his teacher. Li later referred to Fan as “a wolf in sheep’s clothes,” and apparently never forgave him. Although the exact details of their falling out remain unclear, some blame Fan for exploiting Li to further his own career.

There are also some online commenters who call Fan Zeng a “Mr Wang from next door” (隔壁老王), a term jokingly used to refer to the untrustworthy neighbor who sleeps with one’s wife. This is mostly because of the history of how Fan Zeng met his third wife.

Fan’s first wife was the Chinese female calligrapher Lin Xiu (林岫), who came from a wealthy family. During this marriage, Fan did not have to worry about money and focused on his artistic endeavours. The two had a son, but the marriage ended in divorce after a decade. Fan’s second wife was fellow painter Bian Biaohua (边宝华), with whom he had a daughter. It seems that Bian loved Fan much more than he loved her.

It is how he met his third wife that remains controversial to this day. Nan Li (楠莉), formerly named Zhang Guiyun (张桂云), was married to performer Xu Zunde (须遵德). Xu was a close friend of Fan, and helped him out when Fan was still poor and trying to get by while living in Beijing’s old city center.

Wanting to support Fan’s artistic talent, Xu let Fan Zeng stay over, supported him financially, and would invite him for meals. Little did he know that while Xu was away to work, Fan enjoyed much more than meals alone; Fan and Xu’s wife engaged in a secret decade-long affair.

When the affair was finally exposed, Xu Zunde divorced his wife. Still, they would use his house to meet and often locked him out. Three years later, Nan Li officially married Fan Zeng. Xu not only lost his wife and friend but also ended up finding his house emptied, his two sons now bearing Fan’s surname.

When Nan Li passed away in 2021, Fan Zeng published an obituary that garnered criticism. Some felt that the entire text was actually more about praising himself than focusing on the life and character of his late wife, with whom he had been married for forty years.

Fan Zeng and his four wives

An ‘old pervert’, a ‘traitor’, a ‘disgrace’—there are a lot of opinions circulating about Fan that have come up this week.

Despite the negativity, a handful of individuals maintain a positive outlook. A former colleague of Xu Meng writes: “If they genuinely like each other, age shouldn’t matter. Here’s to wishing them a joyful marriage.”

By Manya Koetse

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months ago

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months ago

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago