If you have an affair with a military spouse, it is a criminal offense. But if you’re cheating from within the military, it is not considered a crime against military marriage. On Weibo, the story of one military wife has sparked anger among netizens about the Mao-era military marriage regulations.

An online discussion regarding marriage regulations for military personnel in China has been censored following anger over supposed unequal treatment of “the crime of destruction of the military marriage” (破坏军婚罪).

The discussion was triggered by an online post of a military wife who claimed her husband cheated on her with another female army member. It concerns a Chinese serviceman by the name of Gu Yan (顾炎) and a female officer named Shen Jingwen (沈静雯). The hashtag “Gu Yan, Shen Jingwen” (#顾炎沈静雯#) soon went viral on Weibo.

The lengthy story was originally published on Weibo by Gu Yan’s wife, a medical doctor.

According to the online account, Gu Yan and his wife met each other during their junior high school days, and then each went on to study in different fields. Gu Yan trained to join the army; his wife specialized in the medical field and became an anesthesiologist. The couple got married in 2016, had a child in 2017, and their future looked bright until the husband and wife were separated for eight months during the COVID19 epidemic.

According to Gu’s wife, it was during their long time apart that Gu started seeing Shen Jingwen, an army staff member whose father also serves as a commander in the army. The affair soon became serious, and Gu supposedly became more invested in this new relationship than in his marriage, even to the point of blocking his wife, who then contacted his unit to report the affair.

Gu’s wife alleges that Shen Jingwen threatened and bullied her and that she suffered abuse by her husband. Screenshots and phone conversation recordings to prove this behavior towards Gu’s wife were also leaked online.

In her online post, Gu’s wife indicates that the situation between her, her husband and Shen had become untenable but that she had nowhere to turn to since the existing laws mostly protect those who are serving in the army. Even if she wanted a divorce, she could not get one if he would not want to file for divorce.

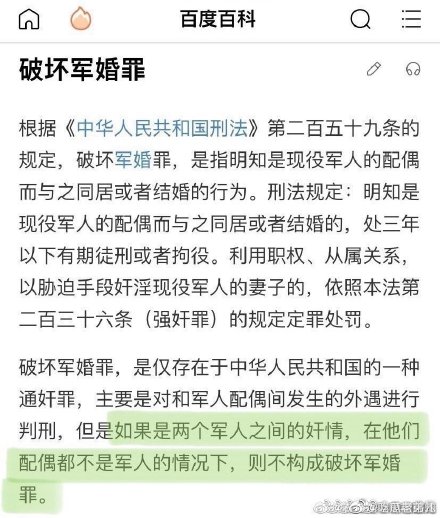

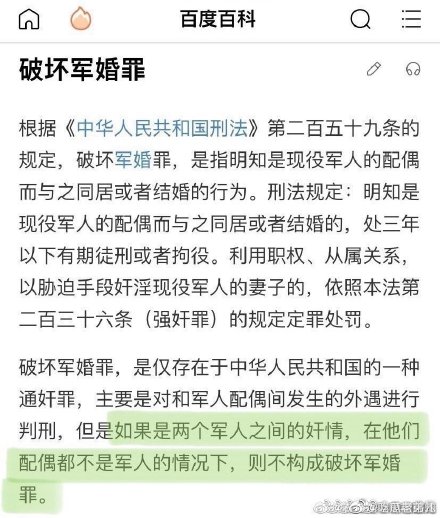

The ‘destruction of military marriage’ (破坏军婚罪) is a criminal offense in China, but in this case, the law did not apply because it concerned a military officer starting an extramarital relationship with another member of military staff. The law mainly focuses on non-marital acts that occur between non-military personnel and military spouses.

The law is a controversial one. As previously explained by Sixth Tone, it is a Mao-era law to prevent military spouses from straying. In 2016, one man from Beijing was prosecuted under the law for living with a soldier’s wife for two months.

In 2019, one man was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment for living together with a military spouse and also fathering her child with prior knowledge that her husband was a serviceman, as reported by China Military.

Although the regulations on the protection of marriage of soldiers date back much longer, breaking up a military marriage was also listed as a criminal offense under “The Offenses Against Marriage and the Family (Arts. 179-184)” in the Criminal Law that was enacted in 1979.

Weibo netizens are sharing screenshots of the Baidu Encyclopedia page explaining the law, with one segment clearly stating that “if it concerns an illicit love affair between two members of the army, and their partners are not members of the army, then this does not constitute as a crime of destructing a military marriage [破坏军婚罪].”

Censorship showed the sensitivity of the topic; not only was it removed from Weibo, but also from other sites such as Q&A site Zhihu.com. The sentence from the Baidu page that was highlighted and shared online also no longer shows up on the Encyclopedia page.

A 404 page comes up when clicking on a page dedicated to this topic on Zhihu.

“The moment this hit the Weibo hot search lists, it was gone within minutes,” one person on a Baidu message board wrote.

The sensitive nature of the topic partly lies in the fact that this is about members of the military, who are usually praised as heroes for their sacrifices for the country.

“To me, the word ‘serviceman’ always sounded like a divine word,” one commenter writes on Weibo: “I’d never expected that it could also bring up loathing in me.”

Meanwhile, many alternative hashtags popped up on social media to replace the censored ones. Besides the “Gu Wen Shen Jingwen” hashtag (#顾炎沈静雯#), there are also many others including “Military Cheating Is Not Considered a Crime against Military Marriage” (#军人出轨不算破坏军婚罪#), “Gu Wen and Shen Jingwen Are Shameless” (#顾炎沈静雯不要脸#) and the creative hashtag “Female Jun People Break Jun Marriage” (#女jun人破坏jun婚#), with ‘jun’ being pinyin for the Chinese character ‘军’ (army).

A mainstream sentiment expressed online is that existing laws regarding military marriages are clearly unfair: anyone who cohabitates with a spouse of an active member of the military could be sentenced, while someone within the military could cheat on their wife without any consequences for them nor for their extramarital sex partner.

Many netizens defend Gu’s wife and condemn Gu and his military girlfriend for abusing their power and taking advantage of their position to bully the weakest party, especially while there is a child involved.

“If a military wife needs to rely on netizens to assert their legitimate marital rights and interests, it really is a disgrace to the Chinese PLA [People’s Liberation Army]”, one blogger wrote.

On the evening of March 19, the Weibo account ‘People’s Frontline’ (@人民前线), an official channel of the People’s Liberation Army, responded to the situation. Their official statement confirms that their department previously received a complaint from Gu’s wife about the living situation of her husband within the army, and that both Gu and Shen were given discipline sanctions. Gu and his wife are currently getting a divorce.

The statement also says that the PLA does not condone the actions of individual members of the army who violate social morals and family virtues. The statement was shared over 18,000 times on Saturday.

Some netizens praised the official statement, saying it showed that the army was becoming more “open and transparent.”

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Leng, Shao-Chuan. 1982. “Crime and Punishment in Post-Mao China.” China Law Reporter 2, no. 1: 5-35.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2021 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months ago

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months ago

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago