China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Series of Shocking Hit-and-Run Incidents: Ruining the Reputation of BMW in China?

The negative news coverage surrounding BMW in China starkly contradicts its marketing image.

Published

1 year agoon

Although it is one of China’s strongest luxury car brands, BMW often makes headlines in China in the context of horrific hit-and-run incidents. Lately, a series of incidents involving BMW drivers ramming into people received a lot of attention on social media. Are the negative headlines impacting BMW’s brand image in China?

Multiple incidents involving BMW drivers driving into crowds of people have attracted online attention in China recently. It is not the first time. BMW hit-and-run cases have made headlines in China since at least two decades ago.

With BMW as a car brand coming up so often in headlines concerning shocking cases, from drunk drivers ramming into people to BMW owners misbehaving in traffic, are attitudes towards the BMW car brand shifting in China?

Here, we will discuss some of the cases that have received a lot of attention on Chinese social media recently, and the role BMW as a brand plays in these discussions.

Three Hit-and-Run Cases Sparking Outrage

Drunk female driver drags victim along for over 1 kilometer in Loudi

On Tuesday, April 11, a court case related to a hit-and-run incident that involved a woman driving a BMW sparked online discussions. The incident happened in September of 2022 in Loudi City, Hunan Province. A female named Xiao (肖) drove into a person on an electrical bike who was then dragged along under the car for a kilometer before the car was finally stopped by traffic police.

Shocking footage of the scene spread online and sparked anger. As the driver was stopped – the victim was still underneath the BMW, – she seemed reluctant to cooperate and was busy staring at her phone. The 28-year-old driver turned out to be driving under influence and was arrested. After being rushed to the hospital, the victim’s condition stabilized.

According to her family, the victim had to stay at the intensive care unit until January of this year. Now, six months later, she is still unable to speak and cannot walk (#宝马女司机撞人拖行案受害者家属发声#).

Once the trial started at the Loudi People’s Court, the incident again went trending, especially because the court decided to postpone its verdict due to the “complexity of the case” (“称因案件疑难复杂将择期宣判”). The woman is accused of causing serious damage or injury while driving (交通肇事罪).

As the victim’s family spoke to reporters in the days leading up to the trial, it also became known that the driver’s family had tried to convince the victim’s husband on three different occasions to sign an apology letter, seeking to mitigate her sentence. They allegedly also told the victim’s family that the driver and her family were also “victims” in this case. This did not exactly help in gaining more sympathy from the public.

Liu Dong drove into Dalian pedestrians to take “revenge on society”

On May 22, 2021, a Saturday morning, a black BMW drove into a crowd of pedestrians in the northeastern Chinese city of Dalian, leaving five people dead and five injured. The driver, who was soon arrested, was a man by the name of Liu Dong (刘东), who reportedly purposely drove into the crowd to take “revenge on society” after an investment failure.

The case recently became trending again because, following his October 2021 trial and death penatly sentencing, Liu Dong was executed on April 7th, 2023.

On social media, the execution attracted a lot of attention. One related hashtag, “Dalian BMW Driver Who Drove Into People Executed by Death Penalty” (#大连宝马撞人案司机被执行死刑#), received over 230 million clicks.

22-year-old man ploughed his car through a busy Guangzhou intersection

Five people were killed and 13 others were injured in a traffic incident involving a BMW driving into pedestrians at Tianhe Road in Guangzhou on January 11, 2023. The incident recently received online attention again due to its similarity with the Dalian hit-and-run.

The incident happened around 17:25 local time. Videos circulating on Douyin and Weibo showed how the black SUV just ploughed his car through the busy street at Tianhe Road/Tiyu East Road, where dozens of people were walking and crossing the intersection. Shortly after the incident, some people could be seen lying motionless on the road.

The driver, who was later filmed driving into other people and throwing money out of his car window, was a 22-year-old man from Jieyang in Guangdong. He was arrested shortly after and there has not been an update in his case since.

The “BMWs Driving Into People” Phenomenon

The three aforementioned incidents are prominent cases in which drivers drove into people. In all of these cases, the BMW car brand was explicitly mentioned in related hashtags and headlines. But these are not the only shocking incidents in which the BMW brand was explicitly mentioned, as there have been so many more “BMW drives into people” cases (宝马撞人案件) throughout the years.

One of the earlier cases happened in October 2003 in Harbin, where a BMW car rammed into a crowd. The incident resulted in the death of one person and injured 12 others. The driver, Su Xiuwen (苏秀文), was later sentenced to two years in prison.

In another well-known incident, a 3-year-old boy in Xinyi, Jiangsu, died under the wheels of a BMW after being run over four times in less than 30 seconds. Although the incident was an accident, the driver drove off and did not even attempt to get help for the child.

In 2016, a BMW driver drove into a crowd in Shenyang, killing two people and injuring six. Other incidents happened in Nanjing (2011/2015), Dongguan (2012), Chengdu (2012), and in many others cities across China where drivers fled the scene after a collision, often causing injuries or killing people.

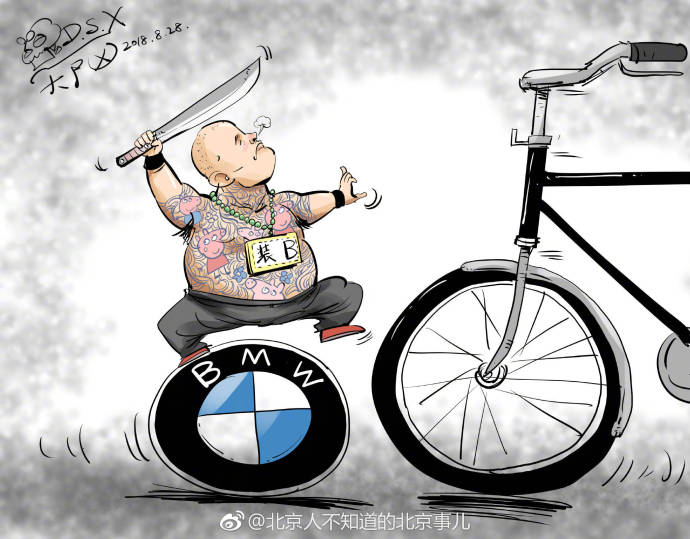

One other case that became one of the biggest trending topics on Chinese social media in 2018 was that of a Kunshan man driving a BMW who got out of his car in an act of shocking road rage, pulling a long knife to attack a cyclist. (In the end, the cyclist was able to grab the knife and he stabbed his attacker, who died from his injuries. The case was later determined to be an act of self-defense, resulting in the cyclists’s acquittal. This decision brought great joy to netizens who had supported the cyclist all along.)

One of the cartoons that was published in the aftermath of the Kunshan BMW incident.

Back in 2010, author Meng Ke already wrote about the phenomenon of “BMWs driving into people” (“宝马撞人”) in China on the Chinese-language BBC website, suggesting the phrase had come to represent “being rich but immoral” (为富不仁). According to the article, the BMW brand was not just gaining a reputation as the car rich people like to drive, but also as the car they were using as a murder weapon.

“I Would Rather Cry in a BMW”

The idea that people driving a BMW are not just rich but also materialistic has been widespread in China for years, also reflected in the phrase “I would rather cry in a BMW” (宁愿宝马里哭) – a famous Chinese catchphrase and meme. The phrase became an online sensation in 2010 after it came up in the popular dating show Fei Cheng Wu Rao (非诚勿扰 If You Are the One).

Ma Nuo (马诺), a 20-year-old female contestant on the show, was asked if she would ride a bicycle with one of the male contestants. In response, she said she would “rather cry in a BMW than smile on a bicycle” (“我宁愿坐在宝马里哭,也不愿坐在自行车里笑”). Soon after, Ma was roasted by Chinese netizens, who attacked her for being a “gold digger” and criticized her for prioritizing material possessions above love. Ma suffered cyber bullying for years.

One reply on a dating show became a part of Chinese meme culture.

While BMW stands for Bayerische Motoren Werke AG, it is sometimes also jokingly said to stand for “Be My Wife,” which actually went viral due to a short Valentine Day film co-created by BMW which was released in 2021 (婚礼, link). It is also said to stand for “Bié Mō Wǒ” (别摸我), meaning “don’t touch me.” This literally conveys the idea of BMW owners being untouchable, and it comes from the popular 2006 film Crazy Stone (疯狂的石头).

From the Crazy Stone movie, when a BMW car owner angrily scolds the person he got into an accident with, saying: “Didn’t you see [the BMW brand,] it stands for Don’t Touch Me (Bie Mo Wo)!”

The popularity of the “rather cry in a BMW,” “Bie Mo Wo,” and “Be My Wife” phrases shows the power of the BMW brand. In the eyes of many, it symbolizes money, capital, and status.

In fact, the success of BMW in the Chinese market – which it entered in 1994 – greatly relies on its brand image of not just producing high-quality, reliable, and superior cars, but also on its brand association with an active, luxurious, and stylish lifestyle (Wang 2013, 107-108).

The negative news coverage surrounding BMW thus starkly contradicts its marketing image, creating a jarring clash between the positive perception of the brand and the unfavorable publicity it has received.

It’s Not the Car, It’s the Rich People Who Drive It

In online discussions surrounding the recent hit-and-run incidents, it is not so much the BMW cars but the rich persons driving them who have a widespread negative reputation. This was also suggested by one popular car blogger on Zhihu (Youshi Qiche @优视汽车), who wrote that BMW owners in China have gotten a notoriously bad name throughout the years.

One study by the Hurun Research Institute on Chinese luxury brands (“中国豪华车品牌特性研究白皮书”) writes that Chinese BMW owners are perceived as being “high-profile and ostentatious, materialistic, showing-off, and lacking a sense of responsibility.” They are also seen as “enjoying new things, good at making friends, seeking social recognition, individualistic and flaunting their wealth.”

Another characteristic attributed to Chinese BMW owners is that they are “profiting without effort” or “reaping what they have not sown,” as they are often associated with China’s nouveau rich (暴发户 bào fā hù) or fù’ér dài (富二代), the ‘second generation rich’ who owe their wealth and lavish lifestyles to their parents’ success under China’s economic reforms.

The BMW driver has gotten a bad reputation, image via Zhihu @优视汽车.

According to Youshi Qiche on Zhihu, some BMW owners only have themselves to blame for the negative stereotypes surrounding them. But what arguably plays a bigger role in their bad image is the social prejudice against those who are perceived as having excessive wealth or privileges, combined with the role media plays in the way they report on BMW owners causing trouble. When an accident involves a BMW or Porsche, it is more likely to be mentioned in the headlines and hashtags.

In many of the aforementioned incidents, but also in others that did not involve a BMW, rich and privileged people causing accidents – deliberately or not, – often try to shift responsibility and use their money, position, or network to avoid punishment.

The most well-known example of this, which has become a part of China’s internet culture, is the “My Dad is Li Gang” incident from 2010. The 22-year-old Li Qiming was drunk driving when he ran down two college students on the campus of Hebei University, killing one of them. When he was arrested after fleeing the scene of the accident, he yelled: “Sue me if you dare! My Dad is Li Gang!” (“我爸是李刚”). Li Gang was the deputy director of the local public security bureau.

“My Dad is Li Gang” instantly became a popular meme in China. Four years later, the sentence “Do you know who my dad is?” (“你知道我爸是谁阿”) became similarly famous after a young man who drove his BMW to school was caught cheating on an exam by a teacher and then intimidated them by suggesting his family was rich and powerful.

Although these incidents happened years ago, the sentiments have largely remained the same, and people are fed up with the careless, agressive and conceited behaviour displayed by nouveau riche who think they are invincible because of their status. These kinds of attitudes are associated with fraud and corruption – a sensitive social problem – and the recent incidents involving BMW drivers further reinforce preconceived beliefs about priviliged and ‘immoral’ BMW owners.

Despite all the negative news coverage in which BMW is mentioned, it is clear that the brand itself is not to blame for these horrific incidents. Nevertheless, the German multinational has shifted its marketing strategies in China over the past years and instead of purely focusing on pleasure, joy, and luxury, it is also placing more emphasis on social values and responsibility. As mentioned by Youshi Qiche, BMW China started sponsoring art and cultural projects, and is playing a role in creating awareness on traffic safety for Chinese children.

BMW China’s changing marketing strategies, images via Youshi Qishe (2021).

BMW’s current Chinese brand ambassador is the wildly popular singer and actor Jackson Yee (易烊千玺), who has a huge fanbase on social media. These kind of marketing strategies resonate with China’s younger generations, for whom the brand image of BMW will probably be different than the associations their parents have with the car.

After all, BMW is generally still seen as a prestigious and high-quality car brand, and it maintains its position as a leading luxury car brand in the Chinese market. Still, not all people prefer a BMW nowadays. “Remember that phrase ‘I’d rather cry in a BMW than smile on a bicycle?’ I’d now say it’s the other way around,” one Weibo user writes.

“I’d rather smile regardless,” another commenter said: “And if I could smile in my own BMW, then I’d go with that one.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

References

Meng Ke (蒙克). 2010. “评论:宝马撞人成了为富不仁的同义词 [Commentary: ‘BMWs Driving Into People’ Has Become Synonymous with ‘the Immoral Rich People’].” BBC, September 14 https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/china/2010/09/100914_analysis_bmw [April 12, 2023].

Wang, Kangmao. 2013. Capital War : How Foreign Companies Fight Their War in China. China MBA Series, Paths International Limited.

Youshi Qiche (优视汽车). 2021. “20年过去了 宝马在国人心目中的品牌形象有改变吗 [After 20 Years, Has BMW’s Brand Image Changed in the Minds of the Chinese?”]. Zhihu, June 9 https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/379235942 [April 12, 2023].

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Books & Literature

Why Chinese Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Shopping Festival

Bookworms love to get a good deal on books, but when the deals are too good, it can actually harm the publishing industry.

Published

2 months agoon

June 8, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

JD.com’s 618 shopping festival is driving down book prices to such an extent that it has prompted a boycott by Chinese publishers, who are concerned about the financial sustainability of their industry.

When June begins, promotional campaigns for China’s 618 Online Shopping Festival suddenly appear everywhere—it’s hard to ignore.

The 618 Festival is a product of China’s booming e-commerce culture. Taking place annually on June 18th, it is China’s largest mid-year shopping carnival. While Alibaba’s “Singles’ Day” shopping festival has been taking place on November 11th since 2009, the 618 Festival was launched by another Chinese e-commerce giant, JD.com (京东), to celebrate the company’s anniversary, boost its sales, and increase its brand value.

By now, other e-commerce platforms such as Taobao and Pinduoduo have joined the 618 Festival, and it has turned into another major nationwide shopping spree event.

For many book lovers in China, 618 has become the perfect opportunity to stock up on books. In previous years, e-commerce platforms like JD.com and Dangdang (当当) would roll out tempting offers during the festival, such as “300 RMB ($41) off for every 500 RMB ($69) spent” or “50 RMB ($7) off for every 100 RMB ($13.8) spent.”

Starting in May, about a month before 618, the largest bookworm community group on the Douban platform, nicknamed “Buying Like Landsliding, Reading Like Silk Spinning” (买书如山倒,看书如抽丝), would start buzzing with activity, discussing book sales, comparing shopping lists, or sharing views about different issues.

Social media users share lists of which books to buy during the 618 shopping festivities.

This year, however, the mood within the group was different. Many members posted that before the 618 season began, books from various publishers were suddenly taken down from e-commerce platforms, disappearing from their online shopping carts. This unusual occurrence sparked discussions among book lovers, with speculations arising about a potential conflict between Chinese publishers and e-commerce platforms.

A joint statement posted in May provided clarity. According to Chinese media outlet The Paper (@澎湃新闻), eight publishers in Beijing and the Shanghai Publishing and Distribution Association, which represent 46 publishing units in Shanghai, issued a statement indicating they refuse to participate in this year’s 618 promotional campaign as proposed by JD.com.

The collective industry boycott has a clear motivation: during JD’s 618 promotional campaign, which offers all books at steep discounts (e.g., 60-70% off) for eight days, publishers lose money on each book sold. Meanwhile, JD.com continues to profit by forcing publishers to sell books at significantly reduced prices (e.g., 80% off). For many publishers, it is simply not sustainable to sell books at 20% of the original price.

One person who has openly spoken out against JD.com’s practices is Shen Haobo (沈浩波), founder and CEO of Chinese book publisher Motie Group (磨铁集团). Shen shared a post on WeChat Moments on May 31st, stating that Motie has completely stopped shipping to JD.com as it opposes the company’s low-price promotions. Shen said it felt like JD.com is “repeatedly rubbing our faces into the ground.”

Nevertheless, many netizens expressed confusion over the situation. Under the hashtag topic “Multiple Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Book Promotions” (#多家出版社抵制618图书大促#), people complained about the relatively high cost of physical books.

With a single legitimate copy often costing 50-60 RMB ($7-$8.3), and children’s books often costing much more, many Chinese readers can only afford to buy books during big sales. They question the justification for these rising prices, as books used to be much more affordable.

Book blogger TaoLangGe (@陶朗歌) argues that for ordinary readers in China, the removal of discounted books is not good news. As consumers, most people are not concerned with the “life and death of the publishing industry” and naturally prefer cheaper books.

However, industry insiders argue that a “price war” on books may not truly benefit buyers in the end, as it is actually driving up the prices as a forced response to the frequent discount promotions by e-commerce platforms.

China News (@中国新闻网) interviewed publisher San Shi (三石), who noted that people’s expectations of book prices can be easily influenced by promotional activities, leading to a subconscious belief that purchasing books at such low prices is normal. Publishers, therefore, feel compelled to reduce costs and adopt price competition to attract buyers. However, the space for cost reduction in paper and printing is limited.

Eventually, this pressure could affect the quality and layout of books, including their binding, design, and editing. In the long run, if a vicious cycle develops, it would be detrimental to the production and publication of high-quality books, ultimately disappointing book lovers who will struggle to find the books they want, in the format they prefer.

This debate temporarily resolved with JD.com’s compromise. According to The Paper, JD.com has started to abandon its previous strategy of offering extreme discounts across all book categories. Publishers now have a certain degree of autonomy, able to decide the types of books and discount rates for platform promotions.

While most previously delisted books have returned for sale, JD.com’s silence on their official social media channels leaves people worried about the future of China’s publishing industry in an era dominated by e-commerce platforms, especially at a time when online shops and livestreamers keep competing over who has the best book deals, hyping up promotional campaigns like ‘9.9 RMB ($1.4) per book with free shipping’ to ‘1 RMB ($0.15) books.’

This year’s developments surrounding the publishing industry and 618 has led to some discussions that have created more awareness among Chinese consumers about the true price of books. “I was planning to bulk buy books this year,” one commenter wrote: “But then I looked at my bookshelf and saw that some of last year’s books haven’t even been unwrapped yet.”

Another commenter wrote: “Although I’m just an ordinary reader, I still feel very sad about this situation. It’s reasonable to say that lower prices are good for readers, but what I see is an unfavorable outlook for publishers and the book market. If this continues, no one will want to work in this industry, and for readers who do not like e-books and only prefer physical books, this is definitely not a good thing at all!”

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Chinese Sun Protection Fashion: Move over Facekini, Here’s the Peek-a-Boo Polo

From facekini to no-face hoodie: China’s anti-tan fashion continues to evolve.

Published

2 months agoon

June 6, 2024

It has been ten years since the Chinese “facekini”—a head garment worn by Chinese ‘aunties’ at the beach or swimming pool to prevent sunburn—went international.

Although the facekini’s debut in French fashion magazines did not lead to an international craze, it did turn the term “facekini” (脸基尼), coined in 2012, into an internationally recognized word.

The facekini went viral in 2014.

In recent years, China has seen a rise in anti-tan, sun-protection garments. More than just preventing sunburn, these garments aim to prevent any tanning at all, helping Chinese women—and some men—maintain as pale a complexion as possible, as fair skin is deemed aesthetically ideal.

As temperatures are soaring across China, online fashion stores on Taobao and other platforms are offering all kinds of fashion solutions to prevent the skin, mainly the face, from being exposed to the sun.

One of these solutions is the reversed no-face sun protection hoodie, or the ‘peek-a-boo polo,’ a dress shirt with a reverse hoodie featuring eye holes and a zipper for the mouth area.

This sun-protective garment is available in various sizes and models, with some inspired by or made by the Japanese NOTHOMME brand. These garments can be worn in two ways—hoodie front or hoodie back. Prices range from 100 to 280 yuan ($13-$38) per shirt/jacket.

The no-face hoodie sun protection shirt is sold in various colors and variations on Chinese e-commerce sites.

Some shops on Taobao joke about the extreme sun-protective fashion, writing: “During the day, you don’t know which one is your wife. At night they’ll return to normal and you’ll see it’s your wife.”

On Xiaohongshu, fashion commenters note how Chinese sun protective clothing has become more extreme over the past few years, with “sunburn protection warriors” (防晒战士) thinking of all kinds of solutions to avoid a tan.

Although there are many jokes surrounding China’s “sun protection warriors,” some people believe they are taking it too far, even comparing them to Muslim women dressed in burqas.

Image shared on Weibo by @TA们叫我董小姐, comparing pretty girls before (left) and nowadays (right), also labeled “sunscreen terrorists.”

Some Xiaohongshu influencers argue that instead of wrapping themselves up like mummies, people should pay more attention to the UV index, suggesting that applying sunscreen and using a parasol or hat usually offers enough protection.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

Duncan

April 17, 2023 at 1:18 am

BMW also stands for ‘Big Money Wasted’, or ‘Break My Windows’. Lol.