Featured

Two Sides of the Olympic Medal: Eileen Gu’s Gold and Beverly Zhu’s Fall on Weibo

Eileen Gu and Beverly Zhu seem similar in many ways, but their Olympic journey in China turned out so differently.

Published

2 years agoon

This week, Chinese social media saw two sides of the Olympic coin. Eileen Gu and Beverly Zhu are both American-born teenagers competing for China in the Olympics, but while Gu was celebrated, Zhu was condemned.

A day after grabbing gold at the Olympics, the 18-year-old Chinese American freestyle skier Gu Ailing (谷爱凌 Eileen Gu) is front-page news in China. She is China’s biggest Olympic social media hit since female swimmer Fu Yuanhui became an online sensation during the Summer Olympics in Rio.

Eileen Gu’s gold medal at the women’s Freeski Big Air final was the third gold medal for China and Gu also became China’s first female gold medalist in snow sports.

Gu is popular for her athletic talent and disarming smile, but the American-born teenager also garnered huge attention online for switching national affiliations and competing for China, a decision she announced in June of 2019. At the time, Gu called the decision “incredibly tough,” writing:

“I am extremely thankful for U.S. Ski & Snowboard and the Chinese Ski Association for having the vision and belief in me to make my dreams come true. I am proud of my heritage and equally proud of my American upbringing. The opportunity to help inspire millions of young people where my mum was born, during the 2022 Beijing Winter Games is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to help to promote the sport I love. Through skiing, I hope to unite people, promote common understanding, create communication, and forge friendships between nations.”

Now, 2.5 years later, Gu has not just won gold, she has also won the hearts of millions of netizens who call her the “snow princess” – the hashtag “Gu Ailing’s Gold Medal” (谷爱凌金牌) received over two billion views on Weibo and the platform’s servers even temporarily went down after Gu’s win (this, by the way, also once happened back in 2017 when Chinese singer and actor Lu Han announced his new relationship).

Gu: An Online Sensation and Rolemodel for Girls

This week, Gu is all over Chinese social media, with videos and images of her epic win dominating feeds on Weibo and Douyin and an advertisement for Chinese sports brand Anta featuring the medalist popping up everywhere. Chinese super celebrities such as Roy Wang (TFBoys) are drawing even more attention to Gu by publicly congratulating her – Wang’s message to Gu received some 400,000 likes on Tuesday.

On February 8, 520 drones formed a portrait of Gu in the city of Sanya to celebrate her gold medal. A video and images of the moment went viral (#三亚520架无人机庆谷爱凌夺金#).

But there is much more. There’s Gu wearing a panda hat, Gu eating dumplings, Gu saying she’s never been to Hainan (#谷爱凌说自己没有去过海南#), Gu talking about how she handles fear (#谷爱凌谈如何应对恐惧#), and then there’s the viral video of her cooking together with her Chinese grandmother (#谷爱凌姥姥冯工#); almost anything Gu does or says nowadays seems to go viral.

It should be noted that the Olympic athlete was already popular before she snatched the gold medal. According to Chinese domestic consumer research platform CBNData, Gu promoted at least twenty brands and companies in 2021 alone, including Anta Sportswear, Midea, Luckin Coffee, China Mobile and Bank of China. Based on the information regarding Gu’s brand endorsement fees, CBNData estimates the teenager must have made at least 200 million yuan ($31,4 million) over the past year for doing work related to promotions and brand ambassadorship.

Gu Ailing promoted at least twenty different brands in 2021.

For many, Gu is an inspiration. The young athlete is hard-working and smart – she was admitted to Stanford – and she is not afraid to speak her mind when reporters ask her tricky questions.

“Gu Ailing’s positivity gives me strength,” one female Weibo user writes:

“She’s dealing with an American upbringing, Chinese ethnic identity, being a girl in extreme sports, public opinions about her nationality, all kinds of people speaking for her, yet she is always outgoing and steady. Really, it doesn’t matter what happens, what matters is what makes you happy. Are you happy in your life? Don’t dwell on loss and regret, ok?”

Debates about Gu’s citizenship have played out across international social media over the past few weeks. Since China does not recognize dual nationality, the general assumption is that athletes like Gu who compete under its banner are required to renounce their non-Chinese citizenship, but reporters’ questions regarding Gu’s current citizenship were recurrently avoided, leading to more speculation on whether or not she actually gave up her American passport or not.

On Chinese social media, many thought these discussions were irrelevant, stressing that Gu represented China for the Olympics now and that the issue of her citizenship was only brought up to polarize.

One Weibo user (@远望白洞) wrote:

“The people who care too much about what nationality she is only want to criticize her for 1) potentially someday returning to US citizenship and 2) using dual citizenship to get special treatment. Either way, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with it. It’s her freedom to go back to the US and the positive effect she has on so many young people will not disappear because of it.”

Eileen Gu and her mother, image published by Sohu.com.

That Gu is praised as an example and role model for women also relates to her background. Gu was raised by her Chinese mother, a molecular biology graduate and former ski instructor, and her maternal grandmother, a former official at China’s Ministry of Transport. Not much is known about who her (American) father is, and it seems clear that the upbringing by these two powerful women has contributed to Gu’s determination and drive, and her own ambition to inspire other girls and young women.

Beverly Zhu: Olympic Cyber Bullying

Just some 48 hours before Gu’s Olympic success, there was the Olympic debut of another US-born athlete representing China. Like Gu, Beverly Zhu is a California-born teenager who changed her citizenship to compete for China during the Winter Olympics. Her parents, both Chinese, moved to the US in the 1990s.

The 19-year-old figure skater announced she would be representing China in September of 2018 and changed her name to Zhu Yi (朱易).

Zhu already was not as popular as Gu on Chinese social media before the Olympics. Her Weibo account has some 110,000 fans, while Gu now has over 4,2 million fans on her personal Weibo page.

But the contrast with her fellow California-born Olympic colleague became even starker when Zhu’s Olympic debut turned out to be somewhat of a disappointment. The athlete ended with the lowest score after she crashed into a wall and failed to correctly land two jumps in the women’s singles short program on Sunday, pushing Team China out of the medals – she was almost unable to hold back her tears.

Afterward, she told reporters:

“I guess I felt a lot of pressure because I know everybody in China was pretty surprised with the selection for ladies’ singles, and I just really wanted to show them what I was able to do, but unfortunately I didn’t.”

Zhu then fell twice in the free skate on Monday, after which she openly sobbed.

During the week, Zhu was criticized and even ridiculed on Chinese social media. There was the Weibo hashtag “Zhu Yi Cries Again in the Arena” (#朱易再度泪洒冰场#), “Zhu Yi Cries” (#朱易哭了#), and “Zhu Yi Fell” (#朱易摔了#), which was later taken offline by online censors along with some ninety Weibo accounts and hundreds of messages bullying Zhu.

But even after the meanest comments were taken offline, Weibo users still expressed their apparent dislike for Zhu. “If you can’t handle the pressure, what are you doing here?”, some said, with others writing: “What is she crying about? It should be us crying while watching her.”

Zhu is by no means the first Chinese female Olympic athlete to experience cyberbullying. During the Tokyo Olympics, athletes Wang Luyao and Yang Qian were also attacked by netizens, showing just how quickly public sentiment can turn against those who are in the limelight.

Did Zhu receive so much criticism just because of her performance, or is there more behind it? For both Zhu and Gu, the fact that they represented China as American-born teenagers automatically meant more eyes were focused on them already.

While Gu seems carefree in talking to the media, Zhu appears more timid and soft-spoken. This might have contributed to Zhu being not as popular online, especially after Zhu cried after her disappointing performance. When Chinese swimmer Fu Yuanhui (傅园慧) became an overnight online sensation during Rio, it was not her bronze medal that made her popular but her enthusiasm and confidence.

Another reason which perhaps prevented Zhu from becoming more of an idol among the public is the fact that there have been many rumors about how Zhu allegedly did “not deserve” her Olympic spot and those regarding her father’s role. Zhu’s father is a renowned Chinese professor who, along with his daughter’s move, also came back to work at prestigious universities in Beijing. It was rumored that Zhu’s father might have helped his daughter get a spot on the Olympic team. Although the rumor was later later refuted, many people were already prejudiced about the young figure skater.

It’s worth noting that there are also hundreds of Weibo users jumping to Zhu’s defense and those condemning the cyberbullying surrounding her. Just like Gu, she sacrificed a lot and worked very hard to get where she is today, even if it did not lead to her grabbing a medal.

There are also those netizens who remind others that Zhu is just a teenager, as is Gu. Some are already worried about Gu’s sudden rise to fame, too. One netizen (@哭泣的空肚子) wrote:

“Fame is a double-edged sword. Your success can be magnified to an extreme, and your mistakes can also be enlarged without boundaries. From now on, she will face the days in which she’ll be carefully walking on the sharp edge of that sword because if she does something that does not conform to what people expect of her, the same people who praise you today will then step on you.”

Perhaps, it is not Zhu Yi but Eileen Gu who will be walking on eggshells for the time to come.

Read more about China and the Olympics here.

By Manya Koetse

With contributions by Miranda Barnes.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Memes & Viral

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Throughout the years, Biden has received many nicknames on Chinese social media.

Published

5 days agoon

July 22, 2024

Our Weibo phrase of the week is Bye Bye Biden (bài bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登). As news of Biden dropping out of the presidential race went viral on Weibo early Monday local time, it’s time to reflect on some of the popular nicknames and phrases given to US President Joe Biden on Chinese social media.

🔹 Biden in Chinese: Bàidēng 拜登

Biden in Chinese is generally written pronounced and written as Bàidēng 拜登. Although the character 拜 (bài) means “to pay respect, to worship” and 登 (dēng) means “to ascend, to climb,” they’re used here primarily for their phonetic similarity. The characters chosen are neutral to avoid any negative implications in the official translation of Biden’s name.

Why are non-Chinese names translated into Chinese at all? With English and Chinese being vastly different languages with entirely different phonetics and scripts, most Chinese people find it difficult to pronounce a foreign name written in English. Writing foreign names in Chinese not only standardizes them but also makes pronunciation and memorization easier for Chinese speakers.

🔹 Bye Biden: Bài Bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登

Because Biden is Bàidēng, and the Chinese for ‘bye bye’ is written as bài bài 拜拜, some netizens quickly created the wordplay “bài bài Bàidēng” 拜拜拜登 (“bye bye Biden”) upon hearing that Biden would not seek reelection. Try saying it out loud—it almost sounds like you’re stammering.

🔹 Old Joe: Lǎo Dēng Dēng 老登登

Another common farewell greeting to Biden seen online is “bài bài lǎo dēng dēng” 拜拜老登登, which sounds cute due to the repetition of sounds.

“Old Biden” or “lǎo dēng dēng” 老登登 is a common online nickname for Biden in Chinese. The reduplication of the 登 (dēng) makes it sound playful and affectionate, while the “old” prefix is commonly used when referring to someone older. It’s similar to calling someone “Old Joe” in English.

🔹 Biden Variations: 拜灯, 白等, 败蹬

Let’s look at some other ways Biden is nicknamed online:

Besides the official way of writing Biden with the 拜登 Bàidēng characters, there are also other variations:

拜灯: bài dēng

白等: bái děng

败蹬: bài dèng

These alternative ways of writing Biden’s name are not neutral. Although the first variation is not necessarily negative (using the formal Biden 拜 bài character but with ‘Light’ 灯 dēng instead of the other 登 ‘dēng’), the other two variations are usually used in more negative contexts.

In 白等 (bái děng), the first character 白 (bái) means “white,” which can evoke associations with old age due to white hair (白发). The character 等 (děng) means “to wait,” and the combination can imply being old and sluggish.

败蹬 (bài dèng) is typically used by netizens to reflect negative sentiments towards the American president. The characters separately mean 败 (bài): “to be defeated,” “to fail,” and 蹬 (dèng): “to step on,” “to kick.” This would never be used by official media and is also often used by netizens to circumvent censorship around a Biden-related topic.

🔹 Revive the Country Biden: Bài Zhènhuá 拜振华

Then there is 拜振华 Bài Zhènhuá: revive the country Biden

In recent years, Biden has come to be referred to with the Chinese nickname “Revive the Country Biden,” also translatable as ‘Thriving China Biden’. This nickname has circulated online since 2020 and matches one previously given to former President Trump, namely “Build the Country Trump” (Chuān Jiànguó 川建国).

The idea behind these humorous monikers is that both Trump and Biden are seen as benefitting China by doing a poor job in running the United States and dealing with China.

🔹 Sleepy King: Shuì wáng 睡王

Shuì wáng 睡王, Sleepy King, is another common nickname, similar to the English “Sleepy Joe.” During and after the 2020 American presidential elections, there were numerous discussions on Chinese social media about ‘Trump versus Biden.’ Many saw it as a contest between the ‘King of Knowing’ (懂王) and the ‘Sleepy King’ (睡王).

These nicknames were attributed to Trump, who frequently boasted about his unparalleled understanding of various matters, and Biden, who gained notoriety for being older and tired. Viral videos, some manipulated, showed him nodding off or seemingly disoriented. The name ‘Sleepy King’ then stuck.

🔹 Grandpa Biden: Bài Yéyé 拜爷爷

Throughout the years, Biden has also been nicknamed Bài yéyé 拜爷爷, “Grandpa Biden.” This is usually more affectionate, though it emphasizes his age—Trump is not much younger than Biden and is not nicknamed ‘Grandpa Trump.’

Another similar nickname is lǎo bái 老白, “Old White,” referring to Biden’s age and white hair. 白 (bái, white) can also be a surname in Chinese. This nickname makes it seem like Biden is an old, familiar friend.

On Weibo, many speculate that American Vice President Kamala Harris will be the new candidate for the Democrats, especially since she’s been endorsed by Biden. Many have little confidence that she can compete against Trump. Her Chinese name is Kǎmǎlā Hālǐsī 卡玛拉·哈里斯, commonly referred to as ‘Harris’ (Hālǐsī).

In light of the latest developments, some netizens jokingly write: “Bye bye Biden, Ha ha ha, Harris.” (Bài bài, Bàidēng. Hā hā hā, Hālǐsī 拜拜,拜登。 哈哈哈,哈里斯). With a new Democratic candidate entering the presidential race, we can expect a fresh batch of creative nicknames to join the mix on Chinese social media.

Want to read more? Also read: Why Trump has Two Different Names in Chinese.

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

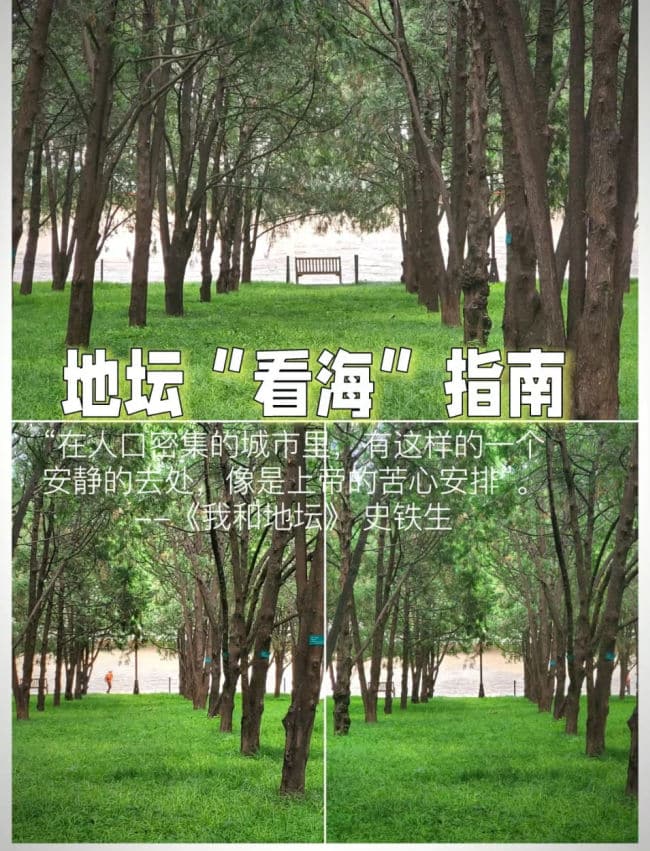

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

This “seaview” spot in Beijing’s Ditan Park has become a new ‘check-in spot’ among Chinese Xiaohongshu users and influencers.

Published

2 weeks agoon

July 15, 2024

“‘The sea in Ditan Park’ is a perfect example of how Xiaohongshu netizens use their imagination to change the world,” a recent viral post on Weibo said (“地坛的海”完全可以入选《红薯人用想象力颠覆世界》的案例合集了”).

The post included screenshots of the Xiaohongshu app where users share their snaps of the supposed seaview in Beijing’s Ditan Park (地坛公园).

Ditan, the Temple of Earth Park, is one of the city’s biggest public parks with tree-lined paths and green gardens in Beijing, not too far from the Lama Temple in Dongcheng District, within the Second Ring Road.

On lifestyle and social media platform Xiaohongshu, users have recently been sharing tips on where and how to get the best seaview in the park, finding a moment of tranquility in the hustle and bustle of Beijing city life.

Post on Xiaohongshu to get the seaview in Ditan Park.

But there is something peculiar about this trend. There is no sea in Ditan Park, nor anywhere else in Beijing, for that matter, as the city is located inland.

The ‘seaview’ trend comes from the view of one of the park’s stone walls. In the late afternoon, somewhere around 16pm, when the sun is not too bright, the light creates an optical illusion from a certain viewpoint in the park, making the wall behind the bench look like water.

You do have to capture the right light at the right moment, or else the effect is non-existent.

Some photos taken at other times of the day clearly show the brick wall, which actually doesn’t look like a sea at all.

Although the ‘seaview in Ditan’ trend is popular among many Xiaohongshu users and influencers who flock to the spot to get that perfect picture, there are also some social media commenters who criticize the trend of netizens always looking for the next “check-in spot” (打卡点).

There are also other spots popular on social media that look like impressive areas but are actually just optical illusions. Here are some examples:

One Weibo user suggested that this trend is actually not about people appreciating the beauty around them, but more about chasing the next social media hype.

The Ditan seaview trend is not entirely new. In May of this year, Beijing government already published a post about the “sea” in Ditan becoming more popular among social media users who especially came to the park for the special spot.

The Beijing Tourism Bureau previously referred to the spot as “the sea at Ditan Park that even Shi Tiesheng didn’t discover” (#在地坛拍到了史铁生都没发现的海#).

Shi Tiesheng (1951–2010) is a famous Chinese author from Beijing whose most well-known work, “Me and Ditan,” reflects on his experiences and contemplations in Ditan Park. At the age of 21, Shi Tiesheng suffered a spinal cord injury that left him paralyzed from the waist down. Ditan Park became a place for him to ponder life, time, and nature. Despite the author’s deep connection with the park, he never described seeing a “sea” in the walls.

Shi Tiesheng in Ditan Park.

If you are visiting Ditan Park and would like to check out the ‘sea’ yourself in the late afternoon, there are guides on Xiaohongshu explaining the route to the viewpoint. But it should not be too difficult to find this summer—just follow the crowds.

By Manya Koetse and Ruixin Zhang

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?