China Media

Zhang versus Zhang: An Online Debate over the Value of Studying Journalism in China

Is pursuing a degree in journalism worth it in China? Educational adviser Zhang Xuefeng says no, while professor Zhang Xiaoqiang says yes. Their online debate has captivated millions of people.

Published

1 year agoon

By

Zilan Qian

Chinese educational internet influencer Zhang Xuefeng (张雪峰) recently sparked a trending discussion by strongly discouraging Chinese youth from pursuing a degree in journalism. While scholars and state media emphasize the merits of studying journalism, a significant number of netizens question its benefits, labeling it as impractical, uneducational, and restrictive.

With the announcement of the 2023 Chinese National College Entrance Examination (Gaokao) scores this week, the process of selecting university preferences has become the focal point for more than 12.9 million families in China.

Zhang Xuefeng (张雪峰), an internet celebrity widely recognized as the “famous teacher for postgraduate entrance exams,” has found himself at the center of an online controversy for advising students against applying for journalism programs.

According to a report by Lianhe Zaobao (联合早报), the incident originated from a livestreamed phone conversation between Zhang Xuefeng and a parent of a student, who was seeking advice.

Upon learning that a science student from Xinjiang had estimated a score of 590 – surpassing the cutoff for admission to first-tier universities, – while expressing an interest in applying for the journalism program at Sichuan University, Zhang Xuefeng reacted with some extreme emotions and remarks.

He advised against pursuing journalism, stating, “Don’t apply for journalism! Any other major you choose blindly would be better than journalism.” He even went as far as saying that if he were the parent, he would “definitely knock the child unconscious if they insisted on studying journalism” (“这孩子非要报新闻学,我一定会把他打晕”).

A screenshot of Zhang Xuefeng’s live stream phone call session in which he dissuaded the student from selecting Journalism. The line reads: “Just don’t select Journalism, ok?”

After a video of their livestreamed conversation was shared by Yan Tu Education, Zhang Xuefeng’s educational company, on their official Douyin account, Zhang’s provocative remarks gained attention from various parties, including journalism scholars and Chinese (state) media outlets.

The ‘Zhang vs Zhang’ online debate started in mid-June when Professor Dr. Zhang Xiaoqiang (张小强) from Chongqing University’s School of Journalism criticized Zhang Xuefeng’s comments, describing them as “harmful and misleading to the public” (“害人不浅,误导公众”).

According to media outlet The Paper, Dr. Zhang argues that the field of journalism is applicable to many different domains, and parents can trust the journalism departments in prominent Chinese universities and colleges.

He believes that the negative perception of the journalism profession stems from the narrow belief that it only leads to careers in traditional media. However, Dr. Zhang asserts that graduates from journalism departments go on to work in various fields.

He suggested that journalism graduates are often recruited for communication roles, and that they can find employment at government organizations, state-owned enterprises, new media companies, or even gaming start-ups. He also cautioned against being deceived by individuals like Zhang Xuefeng, whom he referred to as a mere “internet celebrity.”

Three Reasons Not To Pursue Journalism Major in China

While there are authoritative voices defending journalism education, there is still substantial support for Zhang Xuefeng’s perspective on discouraging journalism as a career choice.

This support mainly stems from three primary reasons: the perceived impracticality of the profession, doubts about the substantive nature and effectiveness of journalism education, and concerns about the limited freedom and liberal values within the field.

1. Not Practical (“无用”)

Firstly, a journalism degree has been deemed as “impractical” as it cannot guarantee good employment prospects.

Zhang Xuefeng dissuades students from pursuing journalism because, according to him, choosing this major would make it hard to secure a livelihood. For families with limited resources, it is important to choose a field of study that is practical and will enable young people to support themselves (“吃上饭”).

He also emphasizes the need to consider real-life circumstances rather than blindly following prescribed norms. Zhang said, “I am not targeting anyone or any specific profession. I am only providing suggestions based on employment situations. If your child cannot find a job, the responsibility lies not with the teachers but with you as parents!”

However, individuals like Dr. Zhang Xiaoqiang strongly oppose such practicalism. On June 17th, during an interview with Fengmian News (封面新闻), Professor Zhang Xiaoqiang stated that the primary consideration for choosing a major should be the student’s interest instead of employability.

Similarly, China Education Daily (中国教育报) published an article titled “Beware of the Misleading Influence of Internet Celebrity Remarks on College Major Selection” (“警惕网红言论误导志愿填报”), condemning Zhang Xuefeng’s statement for being overly arbitrary and shortsighted. The article emphasizes that personal interests and aspirations are also crucial in major selection and encourages young people to dream big and explore uncertainties.

However, many netizens support Zhang’s pragmatic approach and criticize scholars and state media for being overly idealistic and lacking understanding of the difficulties faced by ordinary people, and especially the younger generations, in China today.

The phrase “Why not eat meat?” (“何不食肉糜,” referring to those in positions of power and influence often failing to understand the hardships of common people) has become widely used in this discussion to highlight the discrepancy between scholars and authoritative voices who advocate for choosing majors based on interests and the economic constraints faced by many families.

“The lower the socioeconomic status of the family, the higher the cost of making mistakes in choosing a major, and therefore students should be more cautious in their decision-making,” commented one netizen, contradicting the argument that young people should pursue their passions without considering practicality.

2. Non-Educational (“无学”)

Studying journalism in universities has also faced criticism for being seen as “non-educational” due to the belief that a journalism degree is unnecessary to become a journalist and lacks a substantial theoretical foundation.

The non-profit organization ‘Narada Insights’ (@南都观察) posted an opinion piece by Liu Yuanju (刘远举), a research fellow at the Shanghai Institute of Finance and Law, on their Weibo account. In the piece, Liu highlights the failure of journalism education to provide in-depth content. Writing skills in journalism can be acquired by competent high school graduates, and the ability to gather and evaluate information is a fundamental skill that extends beyond the journalism field, primarily developed through life and work experiences. Therefore, Liu argues, it becomes challenging for students to acquire specific journalism-related skills and knowledge in universities.

Furthermore, Liu points out that journalism is often perceived to have a relatively low entry barrier, as many successful media professionals do not hold journalism degrees at all. On the other hand, knowledge in areas such as science, technology, economics, finance, or law can be advantageous for journalism work. In practice, media organizations often prefer candidates with these kind of educational backgrounds, as they are the ones with specialized expertise in specific industries.

3. Lack of Freedom (“无自由”)

One third complain and common perception of journalism departments is that they primarily teach students how to align with the state’s agenda, which has led to accusations of Chinese journalism being severely restrictive.

Author Liu Shen Leilei (六神磊磊), a former journalist of Politics and Law at the Chongqing Branch of Xinhua News Agency, shared his thoughts on this topic on Weibo. According to Liu, journalism departments lack substantial theories and instead instruct students to be obedient and comply with authorities.

One journalism graduate agreed with Liu’s post, suggesting that they were being compelled to say what the state wants: “I graduated in journalism, and I have a deep aversion to the field. We not only lack the freedom to speak the truth but are also deprived of the freedom to remain silent.”

Even if students possess enough passion to overcome the ‘impractical’ and ‘uneducational’ aspects of journalism education in Chinese universities, they may be disillusioned when they find that the practice of “journalism” in China does not align with their expectations and ideals.

In response to Liu Shen Leilei’s post, another commenter emphasized the profound challenge of reporting the truth in today’s context and asserted that “journalism has died (新闻已死).” This statement reflects the perception that authentic and truthful reporting has become virtually non-existent. Instead, media outlets are believed to employ various tactics to attract attention and disseminate state propaganda. On social media, there is a frequent suggestion to “rename journalism departments as propaganda departments” to reflect this perceived reality.

An End to the Debate?

As the Zhang versus Zhang discussion on pursuing a degree in Journalism continued, Dr. Zhang Xiaoqiang recently took to his social media to express his desire to end the debate, acknowledging the overwhelming criticisms from netizens (#张小强称给自己和张雪峰争论画上句号#, #张小强说和张雪峰争论结束#).

“I still firmly believe that journalism and communication are good majors with promising prospects,” he wrote. “However, media professionals and educators need to foster a positive public opinion and social environment for their own development. We must first prove ourselves.”

Meanwhile, on Chinese social media, various hashtags have emerged in light of this discussion. One of them is “Who Do You Support in the Zhang Xuefeng Journalism Studies Debate?” (#张雪峰新闻学之争你支持谁#), which has reached over 130 million views on Weibo by now.

There even is a possibility to vote on whose side you are.

With more than 42,000 votes, it is clear who the majority of netizens agree with most: 39,000 voters agreed with Zhang Xuefeng that studying journalism is not a favorable option for Chinese young people today.

“They’re starting rumors, smooth things over, and oppose the people,” another person criticizes the state of journalism.

While the debate between Zhang Xuefeng and Professor Zhang Xiaoqiang may have temporarily subsided, the ongoing discourse surrounding the significance of journalism in China is bound to continue.

By Zilan Qian

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Part of featured image via Xigua Shipin.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Zilan Qian is a China-born undergraduate student at Barnard College majoring in Anthropology. She is interested in exploring different cultural phenomena, loves people-watching, and likes loitering in supermarkets and museums.

Also Read

China Media

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Chinese commenters discuss how the bullet aimed at Trump has turned into a moment of triumph.

Published

2 weeks agoon

July 14, 2024

The assassination attempt on former US President Trump at a Pennsylvania campaign event has become a major topic on Chinese social media, where Trump’s swift reaction and defiant gesture after the shooting have not only sparked discussions but also fueled the “Comrade Trump” meme machine.

The chaos that erupted when former US President Trump was injured—a bullet grazing his ear—in an assassination attempt at a Pennsylvania campaign event has become a top trending topic on Chinese social media today.

Trump sustained minor injuries, and the moment he raised his arm to cheer shortly before being evacuated from the stage has already become iconic, captured in widely circulated photographs.

Shortly after the shooting, a shooter armed with a rifle was killed by a US Secret Service counter sniper. The FBI identified the shooter as Thomas Matthew Crooks, a 20-year-old local.

The incident, which occurred on the afternoon of July 13th US local time, resulted in one audience member killed and two others critically injured.

“The campaign efforts will be as smooth as a flying bullet”

On Chinese social media platform Weibo, there are multiple trending hashtags related to the incident, such as “Trump Was Shot” (#特朗普遭遇枪击#, 370 million views); “Trump Says Bullet Pierced His Right Ear” (#特朗普称右耳被子弹击穿#, 440 million views); “Reporter Captures Bullet Grazing Trump’s Ear” (#记者拍到子弹划过特朗普耳朵画面#, 60 million); “Identity of Trump Shooter Confirmed” #枪击特朗普枪手身份确认#, 80 million views). By Sunday afternoon, China local time, half of the top ten hot search topics on Weibo were related to the Trump rally shooting.

“Today, the entire world is watching Trump,” one Chinese Weibo blogger wrote (@乐卡数码).

Political and social commentator Hu Xijin (@胡锡进) reposted a tweet from X by American media influencer Jackson Hinkle, comparing a photo of Trump raising a clenched fist after the shooting to Biden on the ground after falling off his bike near his Delaware home two years ago.

Hu Xijin wrote: “The bullet’s trajectory is so clear, just like how the campaign efforts will now be as fast [smooth] as the flying bullet,” (“好清晰的弹道,和与子弹飞得一样快的助选”).

Post by Hu Xijin

Before this, Hu also commented: “Trump was shot in the ear. This news has shocked everyone. My first reaction after waking up to this news was, ‘how could this happen?’ and I instinctively believe that this incident will garner Trump a lot of sympathy, bringing him one step closer to returning to the White House.”

Media commentator “Media Backpacker” (@媒体背包客) commented on Trump’s quick reaction, noting how he swiftly ducked under the podium after the first shots were fired.

“Several Secret Service agents rushed forward, using their bodies as shields,” he wrote. “Just this scene alone seemed much more professional compared to the attack on Shinzo Abe.” Former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe was shot and killed during a campaign event in the city of Nara, Japan, in 2022.

‘Media Backpacker’ also commented: “The person most harmed by Trump getting injured is not Trump himself, but his opponent, Biden.” Many other Weibo commenters also suggested that this dramatic event is rapidly shifting American voter support toward Trump.

“Just based on his quick reaction and how quickly he crouched, I’d vote Trump. If it were Biden, he probably wouldn’t have been able to crouch at all,” one top commenter on Weibo said.

Another commenter dismissed any rumors of the incident being staged: “It’s impossible to stage this; don’t mythologize the sniper. It’s not that precise. A bullet grazing the ear is extremely, extremely, extremely dangerous. No one would risk their life like that.”

Overall, commenters on Chinese social media suggested that the incident will boost Trump’s popularity and solidify his position in the presidential campaign.

On Sunday afternoon, China local time, official channels reported that Xi Jinping has expressed his sympathies to Trump following the shooting incident in Pennsylvania. China’s Foreign Ministry has also addressed the attempted assassination, expressing concern (#习主席已向特朗普表达慰问#).

“From a journalistic perspective, this is the perfect photo”

Besides online discussions on Trump’s quick reaction and the political implications, there’s a lot of interest in the iconic photo of Trump raising his fist, captured by Evan Vucci, who previously won the Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography for his coverage of George Floyd protests.

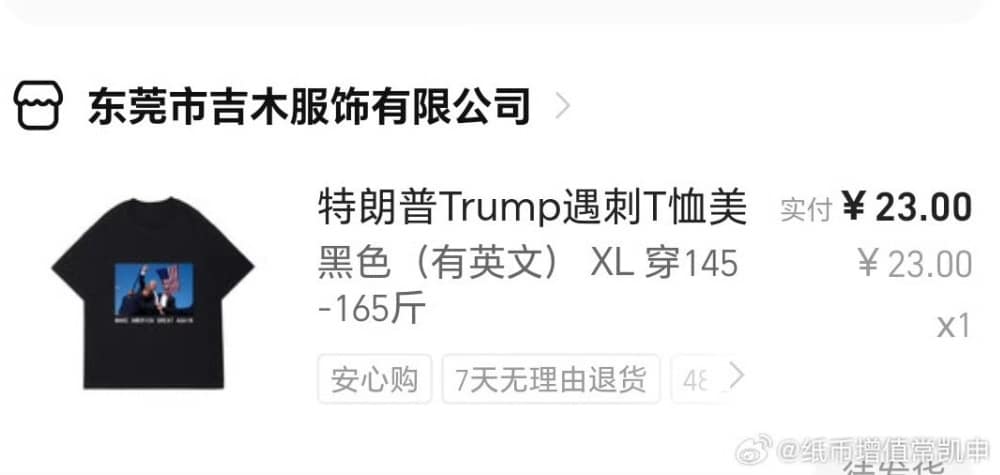

Some netizens noticed that sellers on several Chinese e-commerce platforms soon started selling T-shirts featuring the now famous photo of the incident, priced between 20-49 yuan ($3-$7). Some stores displayed that they had already sold over 10 items, but this merchandise was soon taken offline in various places.

“From a journalistic perspective, this is the perfect photo,” the well-known knowledge blogger Pingyuan Gongzi Zhao Sheng (@平原公子赵胜) wrote: “The destined son of America facing life-threatening danger, his face smeared with blood, with a clenched fist, roaring: “‘Fight! Fight!’ There’s no need to compare anymore; Biden is suffering a crushing defeat, and the Democrats are bewildered. This scene matches the most traditional American image in Hollywood movies. People don’t care who he is or who he serves, but the president must be tough, hard to defeat, a fearless “barbarian,” a “man of steel.”

“Did Trump write the script for Biden’s press conference?”

As this incident is being framed as a triumph for Trump, it further strengthens his position, especially following Biden’s recent damaging performances.

Earlier this week, Biden mistakenly referred to Ukrainian President Zelensky as “President Putin” during the NATO summit, sparking various hashtags on Chinese social media and making Biden a laughing stock for many netizens.

This was not the only mistake Biden made. On Thursday, he mistakenly referred to Vice President Kamala Harris as “Vice President Trump” during his solo press conference in Washington. In that same conference, Biden also talked about “getting Japan and South Korea back together again.”

Another post by American media influencer Jackson Hinkle being shared on Chinese social media platform Weibo.

Following a messy debate performance against Trump on June 27, voices suggesting it may be time for Biden to step down are growing louder. All of this sparked more discussions on Weibo, where many find the situation funny, suggesting: “Did Trump write the script for this [press conference]?”

Now that the bullet aimed at Trump has turned into a moment of triumph, the contrast between the two US presidential candidates has only grown more stark.

“The bullet pierced my ear, but I can still hear the voice of the Party”

On Chinese social media, Trump is often referred to as “Comrade Jianguo” (建国同志 [Comrade Build-Country]), a nickname that has been circulating for years.

Trump is nicknamed “Comrade Trump” or “Build the Country Trump” (Chuān Jiànguó, 川建国) for “making China great again.” These are just some among many existing memes and jokes about the former US president on the Chinese internet. One reason to call him “Comrade Jianguo” or “Build the Country Trump” is to make fun of his words and actions, suggesting that his leadership only brings America down and in doing so, also further accelerates the rise of China.

But through the years, these playful nicknames have started to reflects a blend of mockery and affection, highlighting the humorous perspective Chinese social media users have towards Trump and his political antics (read more).

In a similar tongue-in-cheek fashion, some Weibo users have now edited the iconic Trump photo, portraying him as a communist hero with the caption: “Workers of the world, unite!” (全世界无产者联合起来) (see featured image).

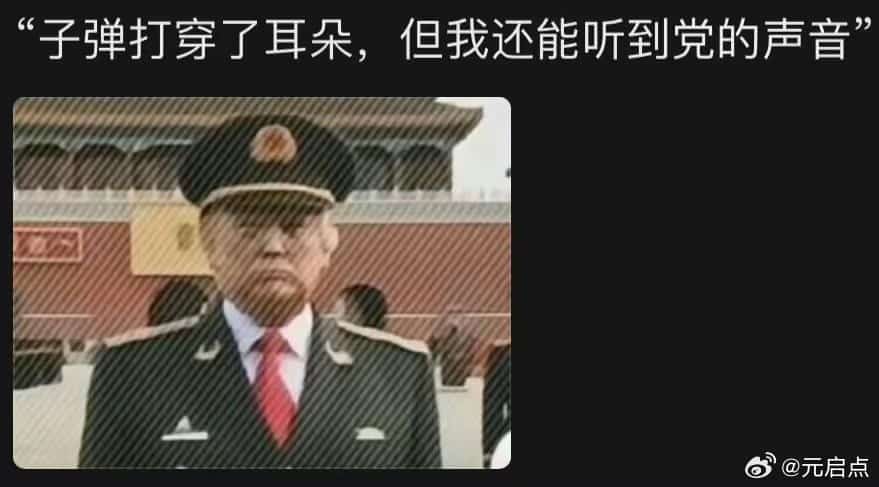

Other similar edits included captions like: “Long live the great and glorious Communist Party of China!” and “The bullet pierced my ear, but I can still hear the voice of the Party.”

Meme: “Long live the great and glorious Communist Party of China!”

Meme: “The bullet pierced my ear, but I can still hear the voice of the Party.”

Some joked that Trump’s right ear being pierced further emphasized his supposed loyalty to China, comparing him to the panda A Bao, who is missing part of his right ear after being bitten by another panda.

Another commenter wrote: “I wish Comrade Jianguo a speedy recovery, may he continue to work hard for the ultimate mission entrusted to him by the Party.”

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Media

The Beishan Park Stabbings: How the Story Unfolded and Was Censored on Weibo

A timeline of the censorship & reporting of the Jilin Beishan Park stabbing incident on Chinese social media.

Published

2 months agoon

June 12, 2024

The recent stabbing incident at Beishan Park in Jilin city, involving four American teachers, has made headlines worldwide. However, on the Chinese internet, the story was initially kept under wraps. This is a brief overview of how the incident was reported, censored, and discussed on Weibo.

On Monday, June 10, four Americans were stabbed while visiting Beishan park in Jilin.

Video footage of the victims lying on the ground in the park was viewed by millions of people outside the Chinese internet by Monday afternoon.

Despite the serious and unusual nature of such an attack on foreigners visiting China, it took about an entire day for the news to be reported by official Chinese channels.

How the Beishan Incident Unfolded Online

In the afternoon of June 10, news about four foreigners being stabbed in Jilin’s Beishan Park started circulating online.

Among the first online accounts to report this incident was the well-known Chinese-language X account ‘Li Laoshi’ (李老师不是你老师, @whyyoutouzhele), which has 1.5 million followers, along with the news account Visegrád 24 (@visegrad24), which has 1 million followers on X.

They both posted a video showing the incident’s aftermath, which soon went viral on X and beyond. It showed how three victims – one female and two male – were lying on the ground at the park, bleeding heavily while waiting for medical help. A police officer was already at the scene.

As soon as the video and tweets triggered discussions in the English-language social media sphere, it was clear that Chinese social media platforms were censoring and blocking mentions of the incident.

By Monday night, China local time, many Weibo commenters had started writing about what had happened in Beishan Park earlier that day, but their posts became unavailable.

Some bloggers wrote about receiving an automated message from Weibo management that their posts had been taken offline. Others started posting about “that thing in Jilin,” but even those messages disappeared. On other platforms, such as Douyin, the story was also being contained.

By 21:00-22:00 local time, a hashtag on Weibo, “Jilin Beishan Park Foreigners” (吉林北山外国人), briefly became the second most-searched topic before it was taken offline. Weibo stated: “According to relevant laws, regulations, and policies, the content of this topic is not shown.”

A hashtag about the Beishan stabbings soon became one of the hottest search queries before it disappeared.

While netizens came up with more creative words and other descriptions to talk about what had happened, the focus shifted from what had happened in Beishan Park to why the topic was being censored. “What’s this? Why can’t we talk about it?” one Weibo user wondered: “Not a single piece of news!”

Around 23:30 local time, another blogger posted: “It seems to be real that four foreigners were stabbed in Jilin’s Beishan Park this afternoon. We’ll have to see when it will formally be reported on Weibo.” Others questioned, “Why is the Jilin incident so tightly covered up on the internet?”

Around 04:00 local time on June 11, the first media outlet to really report on what had happened was Iowa Public Radio (IPR News). Before that time, one Iowan citizen had already commented on X that their sister-in-law was one of the victims involved.

One victim’s family had told IPR News that the individuals involved were four Cornell College instructors. All four survived and were recovering at a nearby hospital after being stabbed during a park visit in China.

The instructors were part of a partnership with Beihua University in Jilin. Cornell College and Beihua University have had an active partnership since 2018, with Beihua funding Cornell instructors to visit China, travel, and teach during a two-week period. Members from both institutions were visiting the public park in Jilin City when they were attacked. The visit was likely intended as a sightseeing and relaxation opportunity during the Dragon Boat Festival holiday, when many people visit the park.

As reported by IPR News reporter Zachary Oren Smith (@ZacharyOS), U.S. Representative Mariannette Miller-Meeks stated that her office was working with the U.S. Embassy to ensure the victims would receive care for their injuries and safely leave China.

Hu Xijin Post

Now that news of the attack on four Americans was all over X, soon picked up by dozens of international news outlets, the Chinese censorship of the story seemed unusual, considering the magnitude of the story.

Furthermore, there had still been no official statement from the Chinese side, nor any news reports on the suspect and whether or not he had been detained.

By the morning of June 11, an internal, unverified BOLO notice from the Jilin city Chuanying police office circulated online. It identified the suspect as 55-year-old Jilin resident Cui Dapeng (崔大鹏), who was still at large. The notice also clarified that there were not four but five victims in total.

At 11:33 local time, it seemed that the wall of censorship surrounding the incident was suddenly lifted when Chinese political and social commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进), who has nearly 25 million followers on Weibo, posted about what had happened.

He based his post on “Western media reports,” and commented that this is a time when Chinese and American sides are actually promoting exchange. He saw the incident as a “random” one, which, regardless of the attacker’s motive, does not reflect broader sentiment within Chinese society. He concluded, “I also hope and believe that this incident will not negatively affect the exchanges between China and the US.”

Hu’s post spurred a flurry of discussions about the Beishan Park incident, turning it into a top-searched topic once again. His comments sparked controversy, with many disagreeing with his suggestion that the incident could potentially affect Sino-American exchanges. Many argued that there are numerous examples of Chinese people being attacked or even murdered in the US without anyone suggesting it would harm US-China relations.

Within approximately two hours of posting, Hu’s post was no longer visible and had disappeared from his timeline. This sudden deletion or blocking of his post again triggered confusion: Was Hu being censored? Why?

Later, screenshots of Hu Xijin’s post shared on social media were also censored.

A “Collision”

By the early Tuesday evening, June 11, Chinese official accounts and state media accounts finally issued a report on what had happened in what was now dubbed the “Beishan Park Stabbing Incident” (#吉林公安通报北山公园伤人案#).

Jilin authorities issued a report on what happened in Beishan Park.

A notice from local public security authorities stated that the first emergency call about a stabbing incident at the park came in at 11:49 in the morning on Monday, June 10, and police and medical assistance soon arrived at the scene.

The 55-year-old Chinese suspect, referred to as ‘Cui’ (崔某某), reportedly stabbed one of the Americans after they bumped into each other at the park (described as “a collision” 发生碰撞). The suspect then attacked the American, his three American companions, and a Chinese visitor who tried to intervene. Reports indicated that the victims were all transported to the hospital and were not in critical condition.

It was also stated that the suspect was arrested on the “same day,” without specifying the time and location of the arrest.

Later on Tuesday, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs addressed the incident during their regular press conference. Spokesperson Lin Jian (林剑) stated that local police had initially judged the case to be a random incident and that they were conducting further investigation (#外交部回应吉林北山公园伤人案#).

Boxer Rebellion References

With the discussions about the incident on Chinese social media less controlled, various views emerged, commenting on issues such as public safety in China, US-China relations, and anti-Western sentiments.

One notable trend during the early discussions of the incident is how many commenters referenced to the ‘Boxer Rebellion’ (1899–1901), an anti-foreign, anti-Christian uprising that took place during the final years of the Qing Dynasty and led to large-scale massacres of foreign residents. Many commenters believed the attacker had nationalist motives targeting foreigners.

Anti-american, nationalist sentiments also surfaced online. Some commenters laughed about the incident or praised the attacker for doing a “good job.”

However, the majority argued that this event should not be seen as indicative of a broader trend of foreign-targeted violence in China. They emphasized that Asians in America are far more frequently targeted in hate crimes than any Westerner in China, underscoring that this incident is just an isolated case.

This idea of the event being “random” (“偶然事件”) was reiterated in official reports, Hu Xijin’s column, and by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

But there are also those who think this might be a conspiracy, calling it bizarre for such a rare incident to occur just when Chinese tourism was finally starting to flourish in the post-Covid era: “Now that our tourism industry is booming, foreigners are getting stabbed? How could it be such a coincidence? Is it possible that this was arranged by spies from other countries?”

On Tuesday, social commentator Hu Xijin made a second attempt at posting about the Beishan Park incident. This time, his post was shorter and less outspoken:

“This appears to be a public security incident,” he wrote: “But this time, four foreign nationals were attacked. In every place around the world, there are criminal and public security incidents where foreigners become victims. China is one of the relatively safest countries in the world, but this incident still occurred in broad daylight in a tourist area. This reminds us, that we need to always keep enhancing the effectiveness of security measures to protect the safety of all Chinese and foreign nationals.”

Again, his post triggered some controversy as some bloggers discovered that Hu had previously argued against extra security checks at Chinese parks, which he deemed unnecessary. They felt he was now contradicting himself.

The differing views on Hu’s posts and the incident at large perhaps explain why the news was initially controlled and censored. Although censorship and control are inherent parts of the Chinese social media apparatus, the level of control over this story was quite unusual. Whether it was due to the suspect still being on the loose, public safety concerns, fears of rising nationalist sentiments, or the need to understand the full details before the story blew up, we will likely never know.

Nevertheless, this time, Hu’s post stayed up.

The Beishan Park incident is reportedly still under investigation.

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?