China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

15 Chinese Ad Campaigns That Make Abortion Procedures Look Glamorous

With pink flowers and dreamlike imageries, these prevalent advertisements promise Chinese women a fast and ‘glamorous’ abortion.

When it is rush hour in Beijing, street marketers often pass out flyers to people around busy subway stations. Most of the time, these pamphlets promote a new neighborhood restaurant or an upcoming real estate project.

Often, however, they promote abortion procedures at a local clinic. The pink and shiny ad campaigns advertise their abortion procedures in similar ways as beauty parlors or nail salons would market their services – a phenomenon which would be unimaginable in many western countries.

China’s “Abortion Culture”

The legal and moral obstacles to abortion that are ubiquitous in the US or elsewhere are much less pervasive in China, a country that has one of the highest abortion rates in the world. According to the National Health and Family Planning Commission, approximately 13 million abortions are carried out in China every year (Yang 2015).

The actual number, however, is probably much higher. The official figures do not include the abortion statistics from private clinics, nor the estimated 10 million induced abortions per year through medicine (Xinhua 2014), let alone the numbers of sex-selective abortions– a practice that has officially been illegal since 2004.

There are various reasons why China’s abortion rates are so high. In “Women’s Health and Abortion Culture in China: Policy, Perception, and Practice,” author Naomi Bouchard describes how the “visible abortion culture” in China today is an (indirect) consequence of the 1979 Family Planning Policy (better known as the One-Child Policy), family pressure, traditional values, and insufficient sexual education (2014, 2).

Especially the last dimension leads to unplanned pregnancies, notably in young women. According to official data, 4% of China’s unmarried female teenagers experience an unplanned pregnancy, with 90% of them ending in abortion (Pan 2013). According to a doctor quoted in Bouchard’s study, it is both lack of knowledge as well as embarrassment about buying condoms or other contraceptives that contributes to unplanned pregnancies in young women (2014, 17).

Thriving Abortion Industry

Besides the social factors that play an important role in China’s “abortion culture,” there is also the legal aspect that makes abortion procedures relatively common in the PRC. Unlike many other countries, China allows abortion for any reason (Theodorou & Sandstrom 2015).

The upper limit for legal abortions depends on circumstances. According to Hemmenki et al (2005), China’s 1979 abortion law sets 28 weeks of gestation as the upper limit for pregnancy termination, although some provinces “have made their own laws stipulating the place and performer of the abortion.” Other literature suggests that there is no limit fixed by statue (Jackson 2013, 423), and that abortions can take place up to the ninth month if the pregnancy is affected by severe anomalies (Deng et al 2015, 312).

All the aforementioned components have led to the existence of a thriving medical industry focused on abortion procedures in China, which comes with a strong commercial marketing of these procedures – advertised anywhere from bus stops to magazines and through flyers.

Scroll through the slider below (move arrows below) to see a selection of 15 advertisements for abortion procedures. The majority of these ads use the color pink and show young women either by themselves or with their partner. Besides addressing the women, their slogans also often speak to their partners (“If you love her, give her the best“).

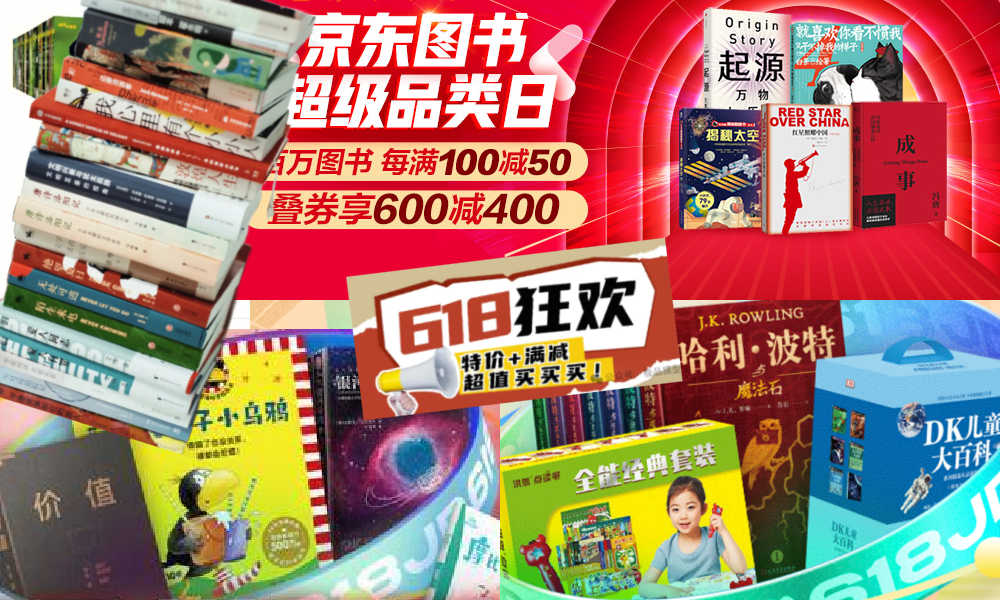

China Books & Literature

Why Chinese Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Shopping Festival

Bookworms love to get a good deal on books, but when the deals are too good, it can actually harm the publishing industry.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Chinese Sun Protection Fashion: Move over Facekini, Here’s the Peek-a-Boo Polo

From facekini to no-face hoodie: China’s anti-tan fashion continues to evolve.

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

Will Kemp

December 13, 2017 at 8:17 am

Generally a wonderful article but the section where you say that condom ads are banned in China isn’t accurate. I live in Chongqing and I can’t move for Durex Air ads at the moment. There’s a video ad in the lift of my apartment building and its being shown before films in the cinema too. Perhaps there was a change in the law?

moxy

March 8, 2018 at 3:23 pm

I know this article was posted quite a while ago, but I feel like the biggest issue you didn’t hit on is that for many of the unmarried women who get pregnant, there’s really not a choice.

If they’re unmarried, and have a kid, that child will never have a Hukou, and is pretty much considered (in the eyes of the government) to be an underworld baby. The child won’t be able to attend school or get any medical, and without initially having a hukou, they can’t do anything to change hukous later on, so pretty much fucked for life.