China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Look Who’s Talking: China’s CCTV Consumer Day Show Accused of Misinformation

Is the pot calling the kettle black?

Published

7 years agoon

The 27th edition of China’s consumer day show ‘CCTV 315 Night’ (315晚会) caused controversy on Chinese social media when it exposed the malpractices in various companies, from Muji stores to Nike shoes. Now that it appears the show itself is negligent with its facts and sources, it is again the talk of the day on Chinese social media. Is the pot calling the kettle black?

World Consumer Rights Day took place earlier this week, and became a trending topic on Sina Weibo (#微博315#) with the release of an annual consumer rights report and a special CCTV program dedicated to protecting consumer rights and uncovering malpractices by companies, called ‘3.15 Night’ (#315晚会#).

The CCTV ‘315 Night’ or ‘consumer day show’ is an annual TV show aired on March 15, focused on naming and shaming various brands and companies.

This year marked the show’s 27th anniversary. As the show featured somewhat more controversial items than it did in previous years, it became the most-discussed topic on Chinese social media on Wednesday and Thursday.

The program revealed several product-related issues that had China’s netizens both worried and skeptical, triggering thousands of shares and reactions across Weibo.

Products from the area of Japan’s Fukushima disaster

One of the program’s items focused on products from those regions in Japan affected by the nuclear crisis of 2011. After the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, the Chinese government introduced various laws to ensure consumer safety and prohibited the import of Japanese products from those areas in Japan affected by nuclear pollution.

But the Chinese TV show now revealed how, six years after the crisis, Japanese food products from the banned areas are allegedly sold in China by several large e-commerce platforms and stores, including Japanese chain store Muji.

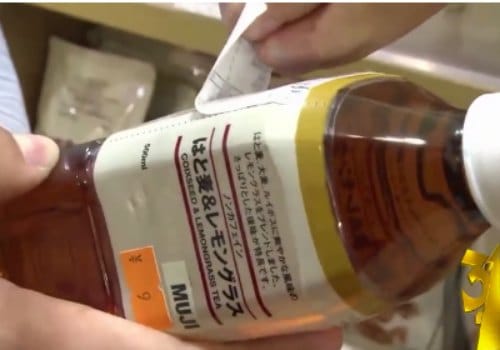

According to the show, retailers hid the origin of the product by using different or vague new labels stating “made in Japan” rather than the specific area from which China has banned the imports of food.

New labels on top of the original ones to hide specific areas of production? Scene from the CCTV 315 Show.

The products included snacks, baby formula, rice, health food, and others, by brands such as Calbee.

News about the imported products led to much anger and commotion on Chinese social media. “Chinese people deceiving Chinese people! The Japanese people won’t eat it so you import it, you do anything for money!”, some angry commenters said.

China’s ‘Wiki’: Selling lies for money

Another scandal revealed by the 315 show concerns Hudong.com (互动百科), China’s homegrown wiki encyclopedia. The platform was accused of false advertising; the mere payment of 4800 RMB (±700$) allows the verification of any product on the site without any other requirements.

The show reported how a patient with liver cancer found a “magic” medicine on Hudong.com as a “verified product”, allegedly able to cure cancer within seven days. Through this kind of false advertising, especially vulnerable people are susceptible to getting fooled into purchasing fake medicine.

Afterward, Chinese media called Hudong “a trash website with the most misleading advertisement” (“互动百科成最大虚假广告垃圾站”).

The negative effects for companies after being featured on the annual consumer rights show cannot be underestimated; in 2015, Forbes called the show a “public relations nightmares for its victims.”

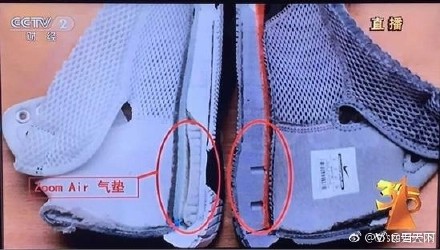

Air Cushion Nikes without the air cushion

The consumer day show also criticized the brand Nike, alleging that the U.S. company’s shoes advertisements are misleading consumers.

The Nike Hyperdunk shoes were promoted to contain the patented zoom air cushions, but were found to actually contain no ‘air cushion’ at all – despite their high price of 1499 RMB (US$220) per pair.

According to Shanghai Daily, over 60 disappointed buyers complained to Nike. The company has since offered them a full refund.

Pot calling kettle black?

The CCTV show’s Nike item again became a point of discussion on Chinese social media today when sport news platform Fastpass (快传体育) complained that the information and images used by CCTV were completely taken from their website, violating their copyright.

In a new article on the Fastpass website, the author says: “CCTV cited its main evidence from our report of November 26 2016 on inspecting the Hyperdunk 08. Not only did CCTV not mention Fastpass as the source, they even used our images without our authorization and took out our watermark.”

Many netizens were confused that the 315 show itself apparently had some malpractices, while its main purpose is to expose the malpractices of others.

“The show is not about ‘protecting consumer rights’ at all it is about knocking out companies in one punch.”

The copyright infringement was not the only point of critique on the show on Chinese social media. Various Chinese media also reported today that the show’s accusations on imported products from Japan’s “banned areas” were ungrounded, as the product package address highlighted during the show is only the place where companies are registered – not where their products are produced.

Furthermore, some netizens wondered why certain controversial products were left out this year: “The Samsung phones have batteries exploding one after the other, why did they not focus on that? Where is their integrity and credibility?”, one commenter wrote.

The fact that ‘Chinese wiki site’ hudong.com was harshly criticized by CCTV while Baidu Baike, its biggest competitor, was not, also annoyed netizens. In 2016, Baidu caused huge controversy for offering advertisement space to fraudulent doctors. These practices came to light when the 21-year-old cancer patient Wei Zexi paid 200,000 RMB (31,000US$) for a treatment promoted through Baidu, which later turned out to be ineffective and highly contested. He died shortly after and received much attention on social media, yet the controversy was not named by the CCTV consumer day show.

One Chinese journalist addressed the TV show on Weibo, writing:

“Some people have asked me what’s up with that 315 Muji report. I did not see the show last night as I was on the train. But even if I had seen it, I would have nothing positive to say about the show. Being a journalist for so many years, I can’t stand this show. It is not about ‘protecting consumer rights’ at all. It is about knocking out companies in one punch. Don’t ask me how I know this.”

“Perhaps it is not a smart move to throw stones while living in a glass house.”

Other commenters also said the show was “fishy”, with many wondering about the selection of the companies it targets, while others are left out. “If they already knew this,” one person said about the alleged imported goods from radiation-polluted areas, “then why would they wait until the night of the show to tell us about it?”

“The show always targets foreign goods, preferably from USA, Japan, and Korea – it not about the product, it is about ideology,” another person (@上善若水之山高) said.

It is not the first time the show has been critized, particularly for bashing foreign brands and products. In 2015, the South China Morning Post also wrote about 315: “(..) the show also had its own “quality problem” – former CCTV financial news channel director Guo Zhenxi, who oversaw 315 Gala, was detained (..) for allegedly taking bribes.”

Overall, many people on Chinese social media simply do not take the show seriously anymore. “Haha, I’ve been hearing all these reports about CCTV 315 on Japanese products these days,” one Weibo user wrote: “You can bash Japanese products all you want, the only thing is that Japanese products undergo very strict supervision and that it’s virtually impossible to bash them!”

It seems that the CCTV show, after running for 27 years, has lost its credibility among the people. Perhaps it is not a smart move to throw stones while living in a glass house; the more critical netizens of today’s online environment can see right through it.

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Books & Literature

Why Chinese Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Shopping Festival

Bookworms love to get a good deal on books, but when the deals are too good, it can actually harm the publishing industry.

Published

2 months agoon

June 8, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

JD.com’s 618 shopping festival is driving down book prices to such an extent that it has prompted a boycott by Chinese publishers, who are concerned about the financial sustainability of their industry.

When June begins, promotional campaigns for China’s 618 Online Shopping Festival suddenly appear everywhere—it’s hard to ignore.

The 618 Festival is a product of China’s booming e-commerce culture. Taking place annually on June 18th, it is China’s largest mid-year shopping carnival. While Alibaba’s “Singles’ Day” shopping festival has been taking place on November 11th since 2009, the 618 Festival was launched by another Chinese e-commerce giant, JD.com (京东), to celebrate the company’s anniversary, boost its sales, and increase its brand value.

By now, other e-commerce platforms such as Taobao and Pinduoduo have joined the 618 Festival, and it has turned into another major nationwide shopping spree event.

For many book lovers in China, 618 has become the perfect opportunity to stock up on books. In previous years, e-commerce platforms like JD.com and Dangdang (当当) would roll out tempting offers during the festival, such as “300 RMB ($41) off for every 500 RMB ($69) spent” or “50 RMB ($7) off for every 100 RMB ($13.8) spent.”

Starting in May, about a month before 618, the largest bookworm community group on the Douban platform, nicknamed “Buying Like Landsliding, Reading Like Silk Spinning” (买书如山倒,看书如抽丝), would start buzzing with activity, discussing book sales, comparing shopping lists, or sharing views about different issues.

Social media users share lists of which books to buy during the 618 shopping festivities.

This year, however, the mood within the group was different. Many members posted that before the 618 season began, books from various publishers were suddenly taken down from e-commerce platforms, disappearing from their online shopping carts. This unusual occurrence sparked discussions among book lovers, with speculations arising about a potential conflict between Chinese publishers and e-commerce platforms.

A joint statement posted in May provided clarity. According to Chinese media outlet The Paper (@澎湃新闻), eight publishers in Beijing and the Shanghai Publishing and Distribution Association, which represent 46 publishing units in Shanghai, issued a statement indicating they refuse to participate in this year’s 618 promotional campaign as proposed by JD.com.

The collective industry boycott has a clear motivation: during JD’s 618 promotional campaign, which offers all books at steep discounts (e.g., 60-70% off) for eight days, publishers lose money on each book sold. Meanwhile, JD.com continues to profit by forcing publishers to sell books at significantly reduced prices (e.g., 80% off). For many publishers, it is simply not sustainable to sell books at 20% of the original price.

One person who has openly spoken out against JD.com’s practices is Shen Haobo (沈浩波), founder and CEO of Chinese book publisher Motie Group (磨铁集团). Shen shared a post on WeChat Moments on May 31st, stating that Motie has completely stopped shipping to JD.com as it opposes the company’s low-price promotions. Shen said it felt like JD.com is “repeatedly rubbing our faces into the ground.”

Nevertheless, many netizens expressed confusion over the situation. Under the hashtag topic “Multiple Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Book Promotions” (#多家出版社抵制618图书大促#), people complained about the relatively high cost of physical books.

With a single legitimate copy often costing 50-60 RMB ($7-$8.3), and children’s books often costing much more, many Chinese readers can only afford to buy books during big sales. They question the justification for these rising prices, as books used to be much more affordable.

Book blogger TaoLangGe (@陶朗歌) argues that for ordinary readers in China, the removal of discounted books is not good news. As consumers, most people are not concerned with the “life and death of the publishing industry” and naturally prefer cheaper books.

However, industry insiders argue that a “price war” on books may not truly benefit buyers in the end, as it is actually driving up the prices as a forced response to the frequent discount promotions by e-commerce platforms.

China News (@中国新闻网) interviewed publisher San Shi (三石), who noted that people’s expectations of book prices can be easily influenced by promotional activities, leading to a subconscious belief that purchasing books at such low prices is normal. Publishers, therefore, feel compelled to reduce costs and adopt price competition to attract buyers. However, the space for cost reduction in paper and printing is limited.

Eventually, this pressure could affect the quality and layout of books, including their binding, design, and editing. In the long run, if a vicious cycle develops, it would be detrimental to the production and publication of high-quality books, ultimately disappointing book lovers who will struggle to find the books they want, in the format they prefer.

This debate temporarily resolved with JD.com’s compromise. According to The Paper, JD.com has started to abandon its previous strategy of offering extreme discounts across all book categories. Publishers now have a certain degree of autonomy, able to decide the types of books and discount rates for platform promotions.

While most previously delisted books have returned for sale, JD.com’s silence on their official social media channels leaves people worried about the future of China’s publishing industry in an era dominated by e-commerce platforms, especially at a time when online shops and livestreamers keep competing over who has the best book deals, hyping up promotional campaigns like ‘9.9 RMB ($1.4) per book with free shipping’ to ‘1 RMB ($0.15) books.’

This year’s developments surrounding the publishing industry and 618 has led to some discussions that have created more awareness among Chinese consumers about the true price of books. “I was planning to bulk buy books this year,” one commenter wrote: “But then I looked at my bookshelf and saw that some of last year’s books haven’t even been unwrapped yet.”

Another commenter wrote: “Although I’m just an ordinary reader, I still feel very sad about this situation. It’s reasonable to say that lower prices are good for readers, but what I see is an unfavorable outlook for publishers and the book market. If this continues, no one will want to work in this industry, and for readers who do not like e-books and only prefer physical books, this is definitely not a good thing at all!”

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Chinese Sun Protection Fashion: Move over Facekini, Here’s the Peek-a-Boo Polo

From facekini to no-face hoodie: China’s anti-tan fashion continues to evolve.

Published

2 months agoon

June 6, 2024

It has been ten years since the Chinese “facekini”—a head garment worn by Chinese ‘aunties’ at the beach or swimming pool to prevent sunburn—went international.

Although the facekini’s debut in French fashion magazines did not lead to an international craze, it did turn the term “facekini” (脸基尼), coined in 2012, into an internationally recognized word.

The facekini went viral in 2014.

In recent years, China has seen a rise in anti-tan, sun-protection garments. More than just preventing sunburn, these garments aim to prevent any tanning at all, helping Chinese women—and some men—maintain as pale a complexion as possible, as fair skin is deemed aesthetically ideal.

As temperatures are soaring across China, online fashion stores on Taobao and other platforms are offering all kinds of fashion solutions to prevent the skin, mainly the face, from being exposed to the sun.

One of these solutions is the reversed no-face sun protection hoodie, or the ‘peek-a-boo polo,’ a dress shirt with a reverse hoodie featuring eye holes and a zipper for the mouth area.

This sun-protective garment is available in various sizes and models, with some inspired by or made by the Japanese NOTHOMME brand. These garments can be worn in two ways—hoodie front or hoodie back. Prices range from 100 to 280 yuan ($13-$38) per shirt/jacket.

The no-face hoodie sun protection shirt is sold in various colors and variations on Chinese e-commerce sites.

Some shops on Taobao joke about the extreme sun-protective fashion, writing: “During the day, you don’t know which one is your wife. At night they’ll return to normal and you’ll see it’s your wife.”

On Xiaohongshu, fashion commenters note how Chinese sun protective clothing has become more extreme over the past few years, with “sunburn protection warriors” (防晒战士) thinking of all kinds of solutions to avoid a tan.

Although there are many jokes surrounding China’s “sun protection warriors,” some people believe they are taking it too far, even comparing them to Muslim women dressed in burqas.

Image shared on Weibo by @TA们叫我董小姐, comparing pretty girls before (left) and nowadays (right), also labeled “sunscreen terrorists.”

Some Xiaohongshu influencers argue that instead of wrapping themselves up like mummies, people should pay more attention to the UV index, suggesting that applying sunscreen and using a parasol or hat usually offers enough protection.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?