China Comic & Games

Playing Around with Tencent: Chinese Parents are Losing a Fortune on Mobile Games

As making in-app purchases has never been easier, Chinese parents are losing thousands of renminbi to virtual weapons.

Published

7 years agoon

With China’s tech giant Tencent being a huge player in both the online gaming and online payment market, making in-app purchases for mobile games has never been easier. Oblivious to the dangers of children playing online, many Chinese parents are losing thousands of renminbi to virtual weapons and armor.

“I will return the money when I am older,” a 9-year-old mobile games fan told Chinese reporters from Pear Video this week.

The third grader from Guiyang, Guizhou, secretly spent over 20,000 RMB (±$3000) of his father’s money on mobile games, buying weapons and armor for his virtual warriors. The boy could effortlessly click from the mobile game to QQ Wallet, one of the Paypal-like online payment platforms by Chinese tech giant Tencent.

The anonymous 9-year-old speaking to Pear Video reporters.

The unexpected financial setback is a big blow to the family. The father makes less than 100 RMB ($14.8) per day. To earn back the money his son spent on online games will cost him seven months of work. The 20,000 RMB was the family’s savings, much needed for their everyday life and their son’s school books.

The young boy started spending the money when he played a popular online mobile fighting game. He wanted to purchase additional in-game features to keep up with his friends, who also play the same game.

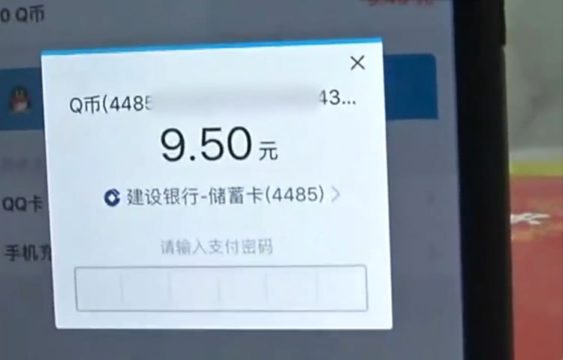

QQ Wallet makes it easy to pay for in-app purchases.

Since the boy knew his father’s QQ Wallet code, he was able to purchase dozens of items through the app without his father knowing.

“This is booming business for Tencent, as it can easily rope in its users across multiple platforms; making the step from WeChat friend groups to mobile games to online payment as small as possible.”

This story is just one among many. At the same time the story of the boy from Guiyang made its rounds on Chinese social media, there was also the story of a 13-year-old from Xianyang who spent 5697 RMB (±$850) in one day on a Tencent mobile game through WeChat Pay. Or that of a junior high school student from Guangzhou spending a staggering 50,000 RMB (±$7400) within one week, buying armor for a game.

In the Xianyang case, the parents of the boy noticed dozens of text messages on their phone when they returned home from work on July 28. They were all confirmation messages from WeChat for mobile payments. The father from Guangzhou told a similar story to Sina News. As many children in China have summer break from school, parents are often at work while the children are at home, and have less overview of what their children are doing.

The game many of these children spent money on is called Crossfire (穿越火线), published by Tencent in China. The game is free to play, but earns its revenues from microtransactions. Players are willing to pay large amounts of money to get better weapons and win territory.

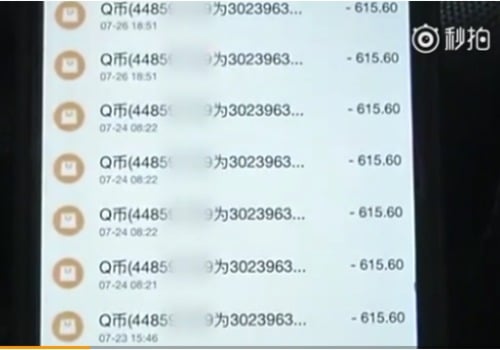

The game is currently among the top downloaded games in the Tencent app store. Its most expensive in-app purchase is almost 616 RMB (±91$); an amount that was spent many times by the 9-year-old boy from Guiyang.

The news report about the 9-year-old boy spending 20,000 RMB on a game shows many transactions of 615; likely concerning Tencent’s Crossfire game.

China has the largest mobile gaming market in the world – and it is a booming business. As China’s leading tech company, Tencent is a dominant player in various fields. It runs messaging platforms QQ and WeChat, online payments solutions Tenpay, QQ Wallet, and WeChat Pay, and also owns a big chunk of China’s online gaming market.

The combination is a golden one for Tencent, as it can easily rope in its users across multiple platforms; making the step from WeChat friend groups to mobile games with in-app purchases to online payment as small as possible.

This is not necessarily a problem when it concerns adult players, but when it concerns kids as young as 9, the game is a trickier one.

“My little brother is crazy about mobile games, and I told him that I will beat him up if he uses our parent’s money to play. Our relative’s son used up 20,000 RMB on mobile games.”

Why do these children know their parents’ payments code? The father from Guangzhou told media reporters he trusted his child and shared his code so they can top up their mobile phone credit if necessary. The 13-year-old boy from Xianyang told Chinese media that he just knew his father’s payment code because he had seen it before. But once he started playing the game, he just kept on going to the next level and lost track of the amount of money he had actually spent.

The game currently has no age restrictions for its players. Recently, however, various media reported that Tencent was limiting the play time for some of its mobile games, restricting players under 12 to play more than an hour per day, to avoid children becoming addicted to mobile gaming.

One Weibo user said: “Lately, there are a lot of mobile games and online games that have many methods to lure users into spending money. Of course, this is one of the main ways for these games to earn money from players, but the people who are running and operating these businesses are not stupid – they know that many of their players are young kids. But still, this is how unscrupulous they are. Doesn’t your conscience bother you?”

Another commenter wrote: “My little brother is crazy about mobile games, and I told him that I will beat him up if he uses our parent’s money to play. We’ve never had a problem. Our relative’s son used up 20,000 RMB on mobile games.”

Many users also stress that parents need to keep their payment identification codes a secret to their children: “Why on earth would you ever tell little kids who cannot control their urges your payment code?”

Some netizens also say that children under the age of 12 should not be allowed to play mobile games at all.

By now, the fathers from Guiyang and Xiangyang have both contacted Tencent to see if they can get some of their money back. In both cases, it is yet unclear if they will succeed in being reimbursed for their children’s games.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Arts & Entertainment

“The End of the Golden Age of Japanese Manga”: Chinese Netizens Mourn Death of Akira Toriyama

Published

5 months agoon

March 8, 2024

Chinese fans are mourning the death of Japanese manga artist and character creator Akira Toriyama. On Friday, his production company confirmed that the 68-year-old artist passed away due to acute subdural hematoma.

On Weibo, a hashtag related to his passing became trending as netizens shared their memories and appreciation for Toriyama’s work, as well as creating fan art in his honor.

The tribute to Toriyama reached beyond online fans – even spokesperson Mao Ning (毛宁) for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China expressed condolences during a regular press conference held on Friday (#外交部对漫画家鸟山明去世表示哀悼#).

Throughout his career, Toriyama created various works, but he is best known for his manga “Dragon Ball,” which was published between 1984-1995 in the magazine Shonen Jump and spawned TV series, films, and video games.

Chinese Love for “Dragon Ball”

Japanese comics and anime have had a significant impact on Chinese popular culture. In China, one of the largest comics markets globally, Japanese manga has been a major import since the 1980s.

Chinese readers form the largest fan community for Japanese comics and anime, and for many Chinese, the influential creations of Akira Toriyama, like “Dr. Slump” and particularly “Dragon Ball,” are cherished as part of their childhood or teenage memories (Fung et al 2019, 125-126).

The cultural link between Toriyama’s “Dragon Ball” and Chinese readers goes further than their mere appreciation for Japanese manga/anime. Toriyama drew inspiration from the Chinese book Journey to the West when he initially created the “Dragon Ball” story. That epic tale, filled with heroes and demons, revolves around supernatural monkey Sun Wukong who accompanies the Tang dynasty monk Xuanzang on a pilgrimage to India to obtain Buddhist sūtras (holy scriptures).

“Dragon Ball” chronicles the adventures of Son Goku, a superhuman boy with a monkey tail, who who is swept into a series of adventures connected to the wish-granting, magical dragon balls, sought after by his evil enemies.

Besides Journey to the West, “Dragon Ball” is filled with many other China-related references and word games, from Chinese mythology to martial arts (Mínguez-López 2014, 35).

In one online poll conducted by Sina News asking Weibo users if “Dragon Ball” is part of their childhood memories, a majority of people responded that the manga series was part of their post-1980s and post-1990s childhood, although younger people also indicated that they loved “Dragon Ball.”

Online Tributes to Toriyama

On Friday, many bloggers and online creators posted images and art to honor Akira Toriyama. Several images went viral and were reposted thousands of times.

Chinese graphic design artist Wuheqilin (@乌合麒麟) dedicated a particularly popular post and image to Toriyama, suggesting that his death symbolized “the end of the golden age of Japanese manga.”

Weibo post by Wuheqilin, March 8 2024.

Shituzi (@使徒子), a Chinese comic artist, posted an image for Toriyama with the words “goodbye.”

Posted by @使徒子.

Chinese comedian Yan Hexiang (阎鹤祥) wrote: “I just bought the Dr. Slump series online. I thank you for bringing me the memories of my childhood, I salute you.”

Weibo is flooded with tribute art honoring Japanese manga artist & Dragon Ball creator Akira Toriyama today. The famous artist, who passed away at the age of 68, holds a special place in the hearts of Chinese fans. This image was shared by Chinese comic artist Shituzi (使徒子) 👇 pic.twitter.com/wsUukRa2dp

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) March 8, 2024

Automotive blogger Chen Zhen (陈震) posted an image of Dragon Ball protagonist Son Goku with wings on his back, waving goodbye, writing: “Rest in peace.”

Image posted by @陈震同学.

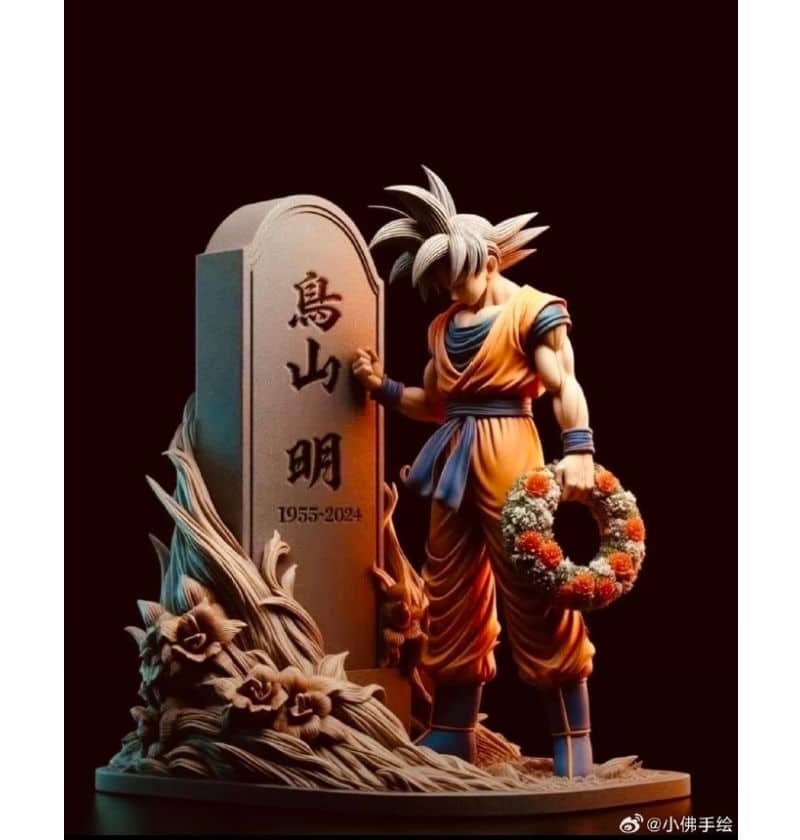

One Dragon Ball fan (@小佛手绘) posted another AI-generated image of Son Goku standing by Toriyama’s grave which was shared all over Weibo.

Posted or reposted by Weibo user @小佛手绘.

By Friday night, the hashtag “Akira Toriyama Passed Away” (#鸟山明去世#) had generated over one billion views on Weibo, showing just how impactful Toriyama’s work has been in China – a legacy that will last long after his passing.

By Manya Koetse

References

Fung, Anthony, Boris Pun, and Yoshitaka Mori. 2019. “Reading Border-Crossing Japanese Comics/Anime in China: Cultural Consumption, Fandom, and Imagination.” Global Media and China 4, no. 1: 125–137.

Xavier Mínguez-López. 2014. “Folktales and Other References in Toriyama’s Dragon Ball.” Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal. Vol. 9 (1): 27–46.

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

China’s XR Development 101: How Chinese Tech Giants are Navigating Towards the Metaverse

Chinese tech giants are massively investing in virtual reality and in the technologies that are building up the Chinese metaverse.

Published

2 years agoon

November 10, 2022By

Jialing Xie

Virtual, Augmented, and Mixed Reality technologies are blurring the lines between the real and digital worlds and are powering the metaverse. Chinese tech giants are at the forefront of the latest developments on the mainland market, including XR, that are making the metaverse possible. Time for a round-up of what China’s key players are focusing on and which virtual initiatives are already live.

2021 is the year in which the concept of ‘metaverse’ has blossomed. In March of last year, the hugely successful online multiplayer game and game creation system Roblox went public with a market value of over $41 billion at the time, earning its reputation as the world’s first metaverse IPO.

Following the release of the 2021 sci-fi comedy Free Guy – which is set in a fictional metaverse-like video game, – and Facebook’s rebranding to ‘Meta’ last fall, ‘metaverse’ became one of the hottest buzzwords on the internet.

The term metaverse is actually decades old. In the 1981 novel True Names, the American computer scientist Vernor Steffen Vinge already envisioned a virtual world that could be accessed through a brain-computer interface, and the term ‘metaverse’ was first mentioned in the 1992 Snow Crash science fiction novel by Neal Stephenson.

Now, 5G, AI, VR, Blockchain, 3D modeling, and other new technologies converged on the concept of the metaverse industry are seeing an explosive growth in China.

At the recent 20th Party Congress, it became clear once again that the digital economy is key in China’s long-term strategies, with Chinese leader Xi Jinping promoting digitalization as one of the new “engines” of future growth.

About Metaverse (元宇宙) in China

In Chinese, ‘metaverse’ is referred to as yuányǔzhòu (元宇宙), which is a literal translation of ‘meta-verse’ – meaning ‘transcending universe’ (超越宇宙). Chinese tech sources also describe the year 2021 as “the metaverse year” (元宇宙元年).

Metaverse is a collective, shared virtual realm that can interact with the real world and where people can interact with each other and the spaces around them. There is not just one single metaverse – there can be many digital living spaces referred to as the ‘metaverse.’

Metaverse is a fluid concept or virtual experience that is still developing and due to the differences in cyber regulations, digital ecosystems, and strict control on online information flows, the Chinese metaverse will unquestionably be very different from the metaverse spheres that companies such as Facebook are working on.

The metaverse is made possible through a wide range of technologies including AI, IoT, Blockchain, Interaction Technology, computer games, and network computing. XR is key to the rise of the metaverse. XR, or Extended Reality, is an umbrella term for a range of immersive technologies including VR (Virtual Reality 虚拟现实), AR (Augmented Reality 增强现实), and MR (Mixed Reality 混合现实). A 2020 Deloitte report suggests that the global XR market consists of mainly VR technologies (48% of market share), followed by AR (34%) and MR (18%).

In December of 2020, Tencent’s CEO Ma Huateng (马化腾) announced the concept of the “All-real Internet” (全真互联网) in a special internal publication regarding the company’s growth and major changes. Ma proposed that the deep integration of the virtual and real world, the “All-real Internet,” is the future opportunity to focus on as the next stage of the (mobile) internet. Although there are some subtle differences, Ma’s idea of the “All-real Internet” overlaps with the concept of the metaverse.

The metaverse, XR, and related technologies are not just a hot issue for Chinese tech companies, they are also an important theme for Chinese authorities. The 20th Party Congress was by no means the first time for China’s leadership to stress the country’s focus on the latest digital innovations. In October 2021, President Xi Jinping also spoke about evolving China’s digital economy during the 19th CPC Central Committee. He asserted that one of the focal points within the development strategy of China’s digital economy is the further integration of digital technologies and real-world economies.

This idea was further clarified in the outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan issued by the State Council at the end of 2021, which listed VR and AR as one of the seven key industries of China’s digital economy along with cloud computing, IoT, AI, and others.

Subsequently, many local governments incorporated metaverse (“元宇宙”) and related relevant terms into their respective 14th Five-Year Plans. For example, Shanghai authorities stated it will focus on the further developments of industries related to quantum computing, 3rd-gen semiconductors, 6G communications, and metaverse.

Here, we will provide an overview of XR industry development in present-day China, going over the key players Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent (BAT) along with the younger Chinese tech giant ByteDance. We provide an overview of what they are investing in, what their respective strategies are when it comes to XR, and give examples of the kind of initiatives that they have already launched. To limit the scope of this article, we have left out Netease, Huawei, Bilibili, and some other relevant Chinese players for now (we might still make a part two later on!).

Key Players and Strategies

▶︎ BAIDU

As one of the leading artificial intelligence (AI) and internet companies in the world, Baidu specializes in internet and AI-related products and services. Baidu is mostly known as China’s number one search engine, but its ambitions go far beyond that. “We want to be like Amazon Web Services (AWS) for the metaverse,” Ma Jie (马杰), vice president at Baidu, recently said.

The company has taken a special interest in building the infrastructure to support metaverse-related projects, deviating from the strategies that focus more on the XR-related content development and distribution that you see at Tencent or Bytedance.

What’s Happening?

Investments

◼︎ iQiyi (爱奇艺), one of China’s top media streaming platforms (sometimes also referred to as the ‘Chinese Netflix’), released its all-in-one virtual reality headset ‘Adventure Dream’ in December 2021 powered by Snapdragon XR2. Baidu owns 53% of iQiyi and holds more than 90% of its shareholder voting rights.

Research & Development

◼︎ Baidu launched the ‘Baidu VR Browser’ on July 15, 2016, becoming China’s first browser powered by webVR technology.

Xirang

◼︎ In 2017, Baidu launched ‘Baidu VR’ platform, which is now offering a wide range of VR-related software and hardware products and services, including the Baidu VR Headset, VR Creation Center, AI app, and XiRang (希壤), which is referred to as China’s “first metaverse platform.”

What’s Live?

Retail

◼︎ In 2018, Baidu VR and UXin Limited, a Chinese online used car marketplace, jointly developed VR 360° interior panoramas that put viewers in the driver’s seat to see how interior details come together and to better understand the details of each vehicle such as scratches, wheels and engine models.

◼︎ Baidu’s ‘Meta Ziwu’ (元宇宙誌屋Meta ZiWU), a virtual space within XiRang, hosts various fashion shows for international brands. In August of 2022, Italian luxury fashion house Prada livestreamed its Fall 2022 collection within the interactive realms of ‘Meta Ziwu,’ and so did Dior, the French fashion house which has also launched its first-ever metaverse exhibition “On the Road” (在路上) via Meta Ziwu.

Social Networking

◼︎ In late 2021, Baidu launched its metaverse project XiRang (希壤, ‘the land of hope’) as “the first Chinese-made metaverse product.” In December, Baidu held ‘Baidu Create 2021′, a three-day annual developers’ conference in a virtual world generated by the XiRang platform, hosting 100,000 people on one set of servers at the same time. Baidu’s Vice President Ma Jie, also Head of the Metaverse XiRang project, shared that the main goal behind this project is to lay the infrastructure of the metaverse by providing developers and content creators with the tools to build their metaverse projects.

Chinese architect Ma Yansong (马岩松), founder of MAD architects, also works together with Meta Ziwu as a virtual architect.

▶︎ALIBABA

Founded in 1999, Alibaba is one of the world’s largest e-commerce and cloud computing companies in Asia Pacific. Its massive success in e-commerce also established Alibaba’s leading position in artificial intelligence and other key technologies that have supported e-commerce, as well as in the future of metaverse.

As one of the biggest venture capital firms and investment corporations in the world, Alibaba struck several deals with prominent XR companies including Magic Leap and Nreal to gain footing in the Extended Reality industry.

As for R&D, Alibaba’s ambition in becoming the world’s fifth-largest economy led to a strong emphasis on technological research and XR-focused innovation and the founding of DAMO Academy.

Within the field of XR, Alibaba primarily focuses on two aspects: underlying technology solutions (e.g. cloud computing) and XR application in its own core business model (e-commerce).

What’s Happening?

Investments

◼︎ In February 2016 and October 2017, Alibaba led the investment rounds in Magic Leap, an augmented reality firm headquartered in Florida.

◼︎ In March of this year, Alibaba led a $60 million investment round of Beijing-based augmented reality glasses maker Nreal. Nreal, founded in 2017, has since launched two AR glasses for the Chinese market: Nreal X for developers and content creators and Nreal Air for regular consumers. Nreal Air glasses have been released in Japan and the UK in February and May of this year. In addition to AR glasses, Nreal also cooperated with iQiyi, China Mobile Migu, Weilai, and Kuaishou to develop AR content.

Research & Development

◼︎ In March 2016, Alibaba announced its own VR research lab, GM LAB ( ‘GnomeMagic’ Lab), which aims to power its e-commerce platform and other subsidiary businesses such as the VR content production for its film and music platforms.

◼︎ Alibaba registered several metaverse-related trademarks, including “Ali Metaverse.”

◼︎ In 2021, Alibaba’s DAMO Academy, a global research program in cutting-edge technologies, launched ‘X Lab’ that focuses on research in key areas related to the metaverse industry, including quantum computing, XR, and xG Technology. Tan Ping (谭平), the former Head of XR Lab, shared several of their ongoing projects at the time. One example he mentioned is the virtual character Xiaomo (小莫), who is very versatile and can, among other things, convert textual information into sign language to enable smoother communication for the hearing impaired.

Xiaomo by Alibaba can turn spoken text into sign language.

‘X Lab’ is also experimenting with making history come alive through virtual initiatives. Recently, Alibaba’s cloud gaming platform Yuanjing made it possible for visitors at their Alibaba Cloud’s Apsara conference to virtually visit the Xi’an Museum and check out its artifacts via mobile phone or laptop, or to have an immersive experience of the Tang dynasty’s imperial palace complex, powered by automatic 3D space creation and visual localization technology.

What’s Live?

eCommerce

◼︎ In November 2016, Alibaba launched the Mobile BUY+ feature in Taobao mobile apps in light of its annual Single’s Day Global Shopping Festival. With VR headsets and the app, China-based Taobao shoppers could experience shopping in-store at Target, Macy’s, or Costco in the US and other malls located in countries such as Japan and Australia.

◼︎ As Alibaba constantly keeps innovating its e-commerce landscape, its research institute DAMO Academy, in collaboration with its licensing platform Alifish, rolled out an XR-powered marketplace on Alibaba’s e-commerce platforms Tmall and Taobao for its November 2022 Single’s Day festival that allows consumers to visit virtual shopping streets and shop for merchandise as their own customizable avatars.

Entertainment

◼︎ In 2021, Alibaba led a $20 million Series A financing round of DGene, a virtual reality and immersive entertainment developer. Among others, DGene creates digital influencers or can even recreate historical figures based on its AI-driven technologies.

Dong Dong was launched as the first virtual brand ambassador for the Winter Olympics in 2022.

◼︎ For the Olympic Winter Olympics in 2022, Alibaba launched Dong Dong, a digital persona developed by Damo Academy using cloud-based digital technologies. Dong Dong was able to engage with fans and online viewers through livestreams, respond to questions in real time, and she even hosted online talkshows.

▶︎TENCENT

As a multinational technology and entertainment conglomerate with the highest-grossing revenue in the world, Tencent has the financial resources to gain an upper hand in technological innovation through acquisition and investment. In 2021 alone, Tencent made a total of 76 investments in Gaming, accounting for 25.2% of Tencent’s total investment throughout the year – a 9.3% increase compared to 2020. Tencent is now the biggest gaming company in the world.

Tencent also ramped up the company’s total headcount working in R&D department by 41%, accounting for 68% of its total workforce in 2021.

Although XR is used to create immersive experiences in different industries including healthcare, manufacturing, or education, its primary fields are still gaming and social – which just so happen to be Tencent’s main focus areas. It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that Tencent, as the country’s Gaming & Social giant, has made XR part of its core business.

What’s Happening?

Investments

◼︎ In 2012, Tencent made an investment in Epic Games, the owner of Unreal Engine which powers well-known video games such as Fortnite, purchasing approximately 40% of the total Epic capital, making it the second largest shareholder. Epic Games’ major businesses span across RT3D game engine (Unreal), in-house developed games (Fortnite), and platform games. This investment is one of the reasons why Tencent conquered a leading position in the metaverse realm when it comes to games.

◼︎ As early as 2014, Tencent already tapped into the VR market by investing in social VR platform AltspaceVR, which was later acquired by Microsoft in 2017.

◼︎ In May 2019, Tencent and Roblox announced a joint venture in which Tencent holds a 49% controlling stake.

◼︎ In September of 2021, Tencent became the new investor behind Beijing-based VR game developer Vanimals (威魔纪元), known for its flagship games Undying and Eternity Warriors VR.

◼︎ In November 2021, Tencent joined the $82M Series D fundraising of Ultraleap, the world leader in mid-air haptics and 3D hand tracking. Ultraleap’s hand-tracking platform has been built into multiple platforms including Qualcomm’s XR and VR devices.

◼︎ In March 2022, Tencent invested in the Chinese AR glasses manufacturer SUPERHEXA (蜂巢科技) holding 7.3% of its shares.

Research & Development

◼︎ In 2015, Tencent announced its avant-garde VR Project ‘Tencent VR,’ a plan consisting of building its own VR games and releasing Tencent Virtual reality software development kits (VR SDKs) to support other VR game developers.

◼︎ As of September 2021, Tencent applied for registration of nearly 100 trademarks related to the metaverse, including “Tencent Music Metaverse” (腾讯音乐元宇宙).

◼︎ In June 2022, Tencent officially set up its XR department led by its Interactive Entertainment Division (IEG) game developer NExT Studios. During Tencent’s annual gaming conference SPARK 2022, the Head of IEG, Ma Xiaoyi (马晓轶), shared Tencent’s ambitions in charting all segments of the VR industry in the next 5 years, from developer software tools and SDKs to VR hardware, to consumer-facing content.

◼︎ NExT Studios, which is the youngest studio within the Tencent Games family, has partnered with the Shenzhen-based FACEGOOD, a 3D content generation technology company that is focused on building metaverse infrastructure.

What’s Live?

Gaming

◼︎ At ChinaJoy 2019, the largest gaming and digital entertainment exhibition across Asia, Tencent launched its cloud gaming solution on its WeGame client, allowing users to play several games instantly without a download. In December of that year, Tencent Games and global leader AI hardware & software leader Nvidia announced a new partnership to launch the START (云游戏) cloud gaming service for PC and console titles.

◼︎ Following the Sino-American joint venture with Roblox in May 2021, Tencent officially launched the Chinese version of Roblox (罗布乐思) topping the App Store free game list in July of 2021.

Social Networking

◼︎ In November 2021, Tencent led a $25 million Series A funding in the British developer Lockwood Publishing best known for the metaverse app Avakin Life, which allows users to create 3D characters and socialize in the virtual community.

◼︎ During the Lunar New Year in February 2022, Tencent’s instant messaging software QQ launched a new feature called “Super QQ Show” (超级QQ秀), which is an upgrade of its ‘QQ Show’ service that’s been running since 2003. Super QQ Show allows users to create their own 3D avatars and use them in an interactive context. It added AI face recognition and rendering. The platform is an interesting one for brands. Fast-food chain KFC even has its own restaurant in this virtual world.

Visiting KFC in the Super QQ Show.

◼︎ In the summer of 2022, the Tencent-backed app developer company Soulgate Inc., which operates the social networking app Soul, applied to be listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Tencent is the largest shareholder holding 49.9% of the shares. Soul is a virtual social playground with the mission of “building a ‘Soul’cial Metaverse for young generations” where users can connect with other users through the virtual identity they develop in the app. The majority of its users, nearly 75%, belong to Gen-Z.

Entertainment

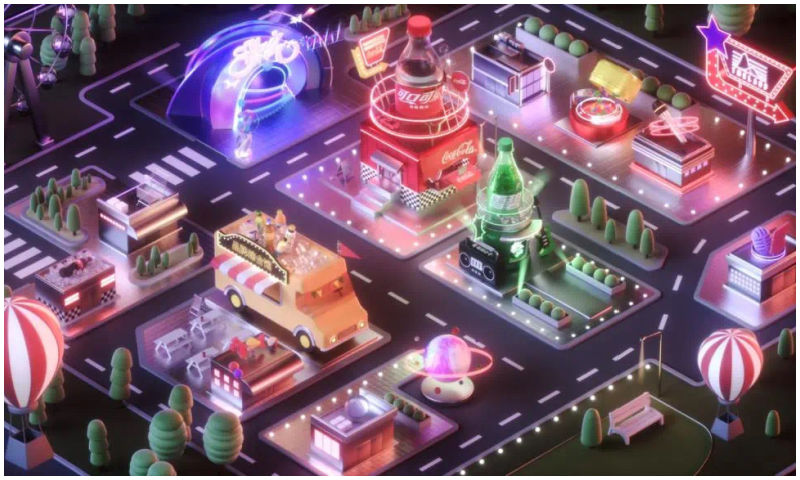

◼︎ On New Year’s Eve of 2021, Tencent Music Entertainment (TME) Group launched China’s first virtual social music platform TMELAND, where users can create their own avatars and interact with each other through their “digital identity.” It’s worth mentioning that TMELAND was powered by the ‘Hybrid Edge-Cloud Platform Solution’ developed by XVERSE (元象科技), which was founded by a former Tencent executive committed to building a one-stop shop for 3D content development.

Coca Cola zone in TMLAND.

Recently, Coca-Cola partnered up with TMELAND to open a new metaverse zone, accessible via the TMELAND mini-programme on WeChat.

▶︎BYTEDANCE

Known as “the world’s most valuable startup,” the Bytedance success story started with the algorithm-powered Toutiao (头条 ‘Headlines’) in 2012, a news and content platform that personalizes content for each user based on their own preferences. The Bytedance app TikTok (Douyin in China) conquered the world as one of most successful Chinese apps internationally.

Bytedance is a social networking leader, but is also focused on its in-house development in VR/AR. By 2021, Bytedance had completed at least 76 investment events, more than the previous two years combined.

From ByteDance’s activities in the XR industry, the company seems to have its strategy primarily focused on hardware, content development, and distribution across gaming, social networking, and entertainment industries.

What’s Happening?

Investments

◼︎ As early as 2018, Toutiao (Bytedance’s core product) acquired VSCENE (维境视讯) a Beijing-based solution provider for VR Live streaming.

◼︎ In July 2020, Bytedance participated in Series A funding of Seizet (熵智科技), an industrial automation company that provides a 3D industrial camera and software.

◼︎ In February 2021, Bytedance invested in Moore Threads (摩尔线程), a company that specialized in visual computing and artificial intelligence fields. In November last year, Moore Threads announced it has developed China’s first domestic full-fledged graphic processing unit (GPU) chip. Along with 5G communications, Wi-Fi 6, cloud computing, and chip technology, GPU is considered one of the main infrastructure technologies of the metaverse.

◼︎ In August 2021, ByteDance acquired Chinese VR hardware maker & software platform Pico for approximately $771 million to support its long-term investment in the VR ecosystem. By the end of Q1 2022, Pico is estimated to hold a 4.5% share of the global VR market, following Meta which is the dominant global player (90%). This year, Bytedance has set a higher sales target for Pico headsets to reach 1.6 million device output. To meet its VR industry goals, Bytedance is investing more into promotion and hiring more staff for Pico to catch up with or even surpass Meta’s Quest.

◼︎ In June 2022, ByteDance acquired PoliQ (波粒子), a team specialized in making virtual social platforms that allow users to interact with one another using their self-invented avatars in the virtual world. Jiesi Ma, the founder of PoliQ, is appointed to lead the VR Social department at ByteDance.

Research & Development

◼︎ To boost its entire VR ecosystem, Pico is engaging in more partnerships with Hollywood’s major film studios and leading streaming media companies in China (iQiyi, Youku, Tencent Video, Bilibili, and so on). In July 2022, Pico hosted Pico WangFeng@VR Music + Drifting Fantasy concert which leveraged 3D 8K VR Live Streaming technology to create a “magical” and immersive visual musical experience. By wearing Pico’s VR headsets, the audience can enjoy Wang’s performance from 5 different angles and as close as a meter away.

What’s Live?

Gaming

◼︎ On February 22, 2021, Bytedance released its game development and publishing brand Nuverse (朝夕光年). To date, Nuverse has launched several successful games through APAC and the western markets including “Burning Streetball” (热血街篮), “Houchi Shoujo” (放置少女), “Ragnarok X: Next Generation” (RO仙境传说:新世代的诞生), “Mobile Legends: Bang Bang”, and “Warhammer 40,000: Lost Crusade.”

◼︎ In April 2021, Bytedance put another US$15 million into Chinese Roblox competitor Reworld (代码乾坤), a platform for creating game worlds and playing games using the company’s own simulation engine.

Social Networking

◼︎ In September 2021, Bytedance launched its avatar app Pixsoul in Southeast Asian markets and Brazil. Users can create personalized avatars and use them to socialize.

◼︎ In January 2022, Bytedance launched a beta version of its virtual social app “Party Island” (派对岛) where users can make friends with people sharing similar interests and hang out with avatars in various virtual settings such as parks and movie theaters. However, the app was reportedly removed from app stores again and its date of relaunching is unknown.

Entertainment

◼︎ In September 2021, TikTok introduced its creator-led NFT collection titled “TikTok Top Moments” where TikTok will feature a selection of culturally-significant TikTok videos from some of the most beloved creators on the platform. Powered by Immutable X, users can ‘own’ a moment on TikTok that broke the internet and trade the TikTok Top Moments NFTs.

Li Weike, image via Pandaily.

◼︎ In January 2022, ByteDance bought a 20% stake in Hangzhou Li Weike Technology Co., Ltd. (Li Weike, 李未可). The company aspires to build China’s first AI+AR-powered glasses that connect users with the virtual idol Li Weike, a digital character built by the company to help users with various tasks and essentially provide users with social and emotional support.

By Jialing Xie and Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get unlimited access to all of our articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?