China Celebs

China’s “Most Famous Foreigner” Mark Rowswell: Ready for Dashan 3.0

He has been China’s most famous foreigner for nearly three decades: Canadian Mark Rowswell aka Dashan. On March 30, he talked about his life as a household name and his work as a comedian in the PRC at Beijing’s the Bookworm. What’s on Weibo was there to take note.

Published

7 years agoon

He is China’s “most famous foreigner” since the late 1980s: Canadian Mark Rowswell, better known as Dashan. On March 30, he talked about his life as a Chinese household name and his work as a comedian at Beijing’s The Bookworm. After a fruitful China career of nearly three decades, Rowswell says he’s now ready for ‘Dashan 3.0.’ What’s on Weibo reports.

Canadian Mark Rowswell aka Dashan (大山) has been working as a comedian and media personality in China since the late 1980s. His excellent Chinese made him instantly famous when he starred in the most-watched televised show in the world, the CCTV Spring Gala. Since then he has appeared on countless Chinese TV shows and dramas, and has appeared on the Spring Gala a total of four times.

On Sina Weibo, Dashan (@大山) now has over 3.8 million fans. He might not be the most popular non-Chinese person on Weibo (Stephen Hawking gained 4.2 million followers since he joined Weibo), but he certainly is the most famous Canadian in China ever since Norman Bethune.

One of the reasons for Rowswell to talk about his work during a special talk at Beijing’s the Bookworm on March 30 (moderated by Asia correspondent Nathan VanderKlippe), is his upcoming show in Australia at the Melbourne Comedy Fest, where he will be performing in Chinese. It’s now all about the physical audiences for Rowswell, who says he’s disappointed with Weibo and the virtual world, and wants to do comedy offline – up close and personal.

THE BIRTH OF DASHAN

“I thought it was just an audience of 500 people; nobody told me there were 550 million people watching the show on TV.”

As Dashan’s career in China will soon hit the 30-year mark, the Ottowa-born performer is perpetually known as “the foreigner who speaks fluent Chinese.”

Perhaps surprising for someone who masters Mandarin so well, Rowswell did not speak a word of Chinese until the age of 19. He chose to study the language out of curiosity after the phrase “the next century belongs to China” started to make its rounds in Canada. From 1984 to 1988, he studied Chinese at the University of Toronto and then headed to China.

Mark Rowswell aka Dashan talks at The Bookworm, March 30.

“We all knew that China was going to be a big part of the world, that many Chinese would come to Canada – but how many Canadians were going to China?”, Rowswell tells his audience at the Bookworm. He set out to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to “ride the wave”, although he was not sure about his exact plans yet.

Within 3 months after starting his studies at Beijing University, Rowswell was asked to participate in a TV show and ‘Dashan’ was born. His Chinese name (that literally means ‘big mountain’) is a peasant one, which in itself already was a joke.

But the name Dashan grew bigger than Rowswell could have ever imagined when he later appeared at the national CCTV gala. “I had no background in performing, and I thought it was just an audience of 500 people; nobody told me there were 550 million people watching the show on television. The little skit that we did somehow hit a sweet spot somewhere, and it ended up being the most popular act of that particular show,” Dashan recalls.

Dashan performing at the 1998 Spring Festival Gala, the best-watched televised event in the world (appears at 3.00 minute mark).

Rowswell’s career soon set off and ‘Dashan’ became a national hype. For a long time, Rowswell did not see his work at the time as a goal in itself: “I thought of it as a stepping stone to get into Chinese society, and to get away from campus and my study books. I traveled with a Chinese performing group and experienced things other foreign students in China would never experience – I even went to places foreigners were not allowed to go.”

Although Rowswell at the time still aspired to work at the Canadian embassy or somewhere else, his work as a freelance performer eventually turned out to be decisive for his eclectic career path, that has brought him to where he is today at the age of 52.

DISAPPOINTED IN SOCIAL MEDIA

“I have trouble reading Weibo because I just don’t find anything interesting on it. It’s very hard to keep engaged on a platform that you don’t find interesting.”

Looking back on the past thirty years, Rowswell says he can roughly divide his story into three parts. “Dashan 1.0” is the foreign student who appeared on TV as a comedian and TV host. That first stage led him to the “2.0” stage, where his role as a freelance performer also grew into one of being more of a cultural ambassador.

Rowswell received official recognition for this cultural role when he was part of Canada’s Team Attaché during the 2008 Olympics, and later became the Commissioner General for Canada at Expo 2010 in Shanghai. After this period, he searched for a new goal and hoped to find it online.

“After 2010 I thought the answer was Weibo,” Rowswell says: “I really got into Weibo around 2010, 2011, 2012. But post-2012 or so, Weibo is really…I mean, I still maintain it, but I really have trouble reading Weibo now because I just don’t find anything interesting on it. It’s very hard to keep engaged on a platform that you don’t find interesting.”

Rowswell expresses his disappointment when he says he feels that “the promise of social media has not played out.” Although he says he thought that internet was the channel to lead the next stage of his career, “it did not work out that way.”

It is not just Sina Weibo that has not brought Dashan what he had hoped for: “I just think social media in general.. (..) We used to think technology was going to make it easier to communicate and that social media was going to bring people together but that has not worked; social media has unleashed the basic human tribalism and reinforced it.”

As Rowswell felt that the future of his career would not take place online in front of a virtual audience, he decided to focus on physical audiences and returned to the offline stage.

THE THIRD ACT

“Stand-up comedy is something that is closely tied to the rise of counter-culture and individualism in China.”

From foreign comedian to cultural ambassador, Rowswell reveals that he has always felt he was not truly doing his own things as a freelancer. “I was always doing stuff for someone else, doing someone else’s show. But where is my show?!,” he laughingly says.

It is stand-up comedy in which Dashan has found the next stage of his career, which he calls “Dashan 3.0” or “the third act.” Rowswell stresses that he does not want to be the foreigner in China performing solely for foreign audiences in expat bars. He specifically wants to connect with Chinese audiences; Chinese-language comedy is giving Dashan the stage and the possibility to directly speak to them.

As stand-up comedy (站立喜剧) is finding more channels and bigger audiences in China, Rowswell feels this is the right niche to explore: “It allows me to build on something new. It is not mainstream comedy here, but is something that is closely tied to the rise of counter-culture and individualism in China.”

Rowswell also finds that his eclectic career and experiences now give him the opportunity to take on some kind of mentoring role as a performer. The upcoming Chinese “Dashan Live” show at the Melbourne International Comedy Festival – where he will be the only “non-Chinese Chinese performer” – is an important part of this new journey.

“It takes time to find your own voice,” Rowswell remarks. As Dashan 3.0, he now has the opportunity to finally share his own experiences and his own stories, in his own Dashan show.

“Dashan Live” will take place from April 12-16 at The Forum, Melbourne.

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Arts & Entertainment

Jia Ling Returns to the Limelight with New “YOLO” Movie and 110-Pound Weight Loss Announcement

After a year away from the spotlight, Chinese actress and director Jia Ling is back, announcing both a new film and slimmer figure.

Published

7 months agoon

January 11, 2024

Chinese actress and director Jia Ling (贾玲) has been trending on Weibo thanks to her upcoming film YOLO (热辣滚烫) and her remarkable weight loss transformation.

Jia Ling is a famous Chinese comedian actress, known for her annual Spring Festival Gala performances. She has been especially successful in the previous years as she made her directorial debut in 2021 with the award-winning box office hit Hi, Mom (Chinese title Hi, Li Huanying 你好,李焕英), in which she also stars as the female protagonist. That same year, audiences saw her as Wu Ge in Embrace Again (穿过寒冬拥抱你).

It has been a while since we’ve heard from Jia Ling, but on January 11, she resurfaced with a Weibo post in which she explained her absence from the limelight.

In her post, Jia wrote that she has spent the entire year working on the YOLO (热辣滚烫) movie, for which she lost a staggering 100 jin (斤) (110 lbs/50 kg). Just as with Hi, Mum, Jia is both the director of YOLO and the lead actress.

According to Jia, it was a tiring and “hungry” year, during which she ended up “looking like a boxer.” She added that the movie, set to premiere during the Spring Festival, is not necessarily about weight loss at all, but about learning to love yourself.

Within a single day, Jia Ling’s post received nearly 60,000 replies and over 855,000 likes.

Jia Ling’s post on Weibo.

The topic became top trending due to various reasons. It is because fans are excited to see Jia Ling back in the limelight and are anticipating the upcoming movie, but also because they are eager to see Jia Ling’s transformation.

From fans on Weibo: Jia Ling fanart and a meme from one of her well-known Spring Festival performances.

A short scene from the movie showed Jia Ling’s slimmer appearance, and a screenshot of it went viral, with Weibo users saying they hardly recognized Jia anymore.

One hashtag related to Jia Ling’s weight loss, about expert views on losing so much weight in such a relatively short time, received over 450 million on Weibo on Thursday (#医生谈贾玲整容式暴瘦#).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, medical experts quoted by Chinese media outlets caution against rapid weight loss methods, recommending a more gradual approach instead.

Nevertheless, there is great interest in the extreme diets of Chinese celebrities. As discussed in an earlier article about China’s celebrity weight craze, the weight loss journey of Chines actors or influencers often capture widespread attention as people are keen to adopt diet plans promoted by celebrities.

YOLO (热辣滚烫), which will hit Chinese theaters on February 10, tells the story of Le Ying (乐莹), who has withdrawn from social life and isolated herself at home ever since graduation. Trying to get her life back on track, Le Ying meets a boxing coach. The meeting proves to be just the beginning of a new journey in life filled with unforeseen challenges.

The Spring Festival holiday typically sees peak box office numbers in China, making this movie highly anticipated, particularly after the success of Hi, Mum three years ago. On Weibo, many view Jia Ling’s weight loss as a testament to her dedication and are eager to see the results of her year-long efforts in the cinema next month.

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Celebs

Three Reasons Why Lipstick King’s ‘Eyebrow Pencil Gate’ Has Blown Up

From beauty guru to betrayal: why one livestream moment is shaking China’s internet.

Published

11 months agoon

September 13, 2023

PREMIUM CONTENT

Li Jiaqi, also known as Austin Li the ‘Lipstick King,’ has become the focus of intense media attention in China over the past days.

The controversy began when the popular beauty influencer responded with apparent annoyance to a viewer’s comment about the high price of an eyebrow pencil. As a result, his fans began unfollowing him, netizens started scolding him, Chinese state criticized him, and the memes started flooding in.

Li Jiaqi’s tearful apology did not fix anything.

We reported about the incident here shortly after it went trending, and you can see the translated video of the moment here:

China's famous make-up influencer #LiJiaqi is in hot water due to an e-commerce livestream he did on Sunday. When viewers complained about an eyebrow pencil being too expensive (79 RMB/$10.9), he got annoyed, insisting that the product was not expensive at all. Translated video: pic.twitter.com/JDKGMKovDX

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) September 11, 2023

The incident may seem minor at first glance. Li was merely promoting Florasis brand (花西子) eyebrow pencils, and some viewers expressed their opinion that the pencils, priced at 79 yuan ($11), had become more expensive.

In response, Li displayed irritation, questioning, “Expensive how?” He went on to suggest that viewers should also reflect on their own efforts and whether they were working hard enough to get a salary increase.

But there is more to this incident than just an $11 pencil and an unsympathetic response.

#1 The King Who Forgot the People Who Crowned Him

The initial reaction of netizens to Li Jiaqi’s remarks during the September 10th livestream was characterized by a strong sense of anger and disappointment.

Although celebrities often face scrutiny when displaying signs of arrogance after their rise to fame, the position of Li Jiaqi in the wanghong (internet celebrity) scene has been especially unique. He initially worked as a beauty consultant for L’Oreal within a shopping mall before embarking on his livestreaming career through Alibaba’s Taobao platform.

In a time when consumers have access to thousands of makeup products across various price ranges, Li Jiaqi established himself as a trusted cosmetics expert. People relied on his expertise to recommend the right products at the right prices, and his practice of personally applying and showcasing various lipstick colors made him all the more popular. He soon garnered millions of online fans who started calling him the Lipstick King.

By 2018, he had already amassed a significant fortune of 10 million yuan ($1.53 million). Fast forward three years, and his wealth had ballooned to an astonishing 18.5 billion yuan ($2.5 billion).

Despite his growing wealth, Li continued to enjoy the support of his fans, who appreciated his honest assessments of products during live testing sessions. He was known for candidly informing viewers when a product wasn’t worth buying, and the story of his humble beginnings as a shop assistant played a major role in why people trusted him and wanted him to succeed.

However, his recent change in tone, where he no longer seemed considerate of viewers who might find an $11 brow pencil to be expensive, suggests that he may have lost touch with his own customer base. Some individuals perceive this shift as a form of actual “betrayal” (背叛), as if a close friend has turned their back on them.

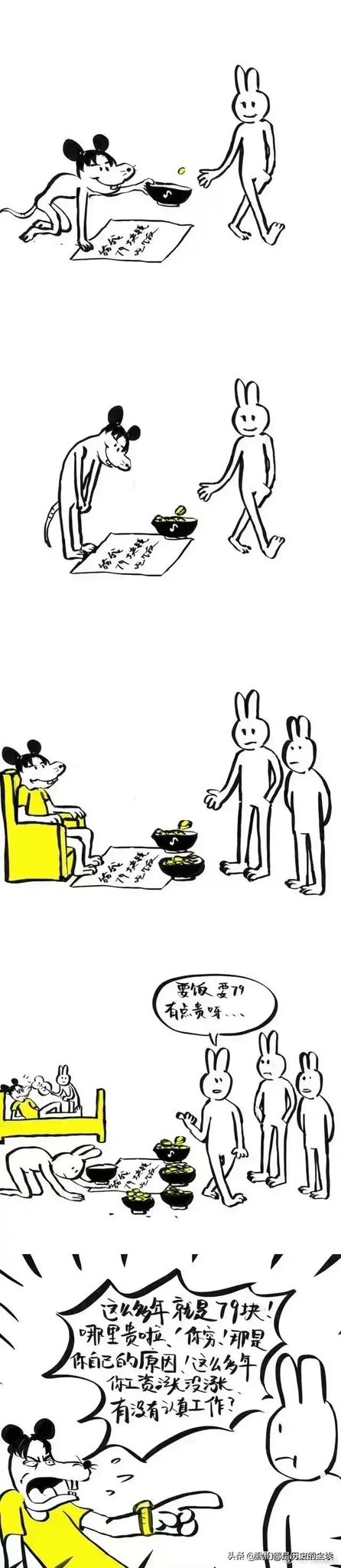

The viral cartoon shows Li Jiaqi going from a friendly beggar to angry rat.

One cartoon shared on social media shows Li Jiaqi, with mouse ears, as he initially begs his online viewers for money. However, as he becomes more prosperous, the cartoon portrays him gradually growing arrogant and eventually scolding those who helped him rise to fame.

Many people accuse Li of being insincere, suggesting that he revealed his true colors during that short livestream moment. This is also one of the reasons why most commenters say they do not believe his tears during his apology video.

“He betrayed China’s working class,” one popular vlog suggested.

#2 Internet Celebrity Crossing the Lines

Another reason why the incident involving Li Jiaqi is causing such a storm is related to the media context in which Chinese (internet) celebrities operate and what is expected of them.

Whether you are an actor, singer, comedian, or a famous livestreamer/e-commerce influencer, Chinese celebrities and performers are seen as fulfilling an exemplary role in society, serving the people and the nation (Jeffrey & Xu 2023). This is why, as explained in the 2019 research report by Jonathan Sullivan and Séagh Kehoe, moral components play such a significant role in Chinese celebrity culture.

In today’s age of social media, the role of celebrities in society has evolved to become even more significant as they have a vast reach and profound influence that extends to countless people and industries.

Their powerful influence makes celebrities important tools for authorities to convey messages that align with their goals – and definitely not contradict them. Through the media and cultural industries, the state can exert a certain level of control within the symbolic economy in which celebrities operate, as discussed by Sullivan and Kehoe in their 2019 work (p. 242).

This control over celebrities’ actions became particularly evident in the case of Li Jiaqi in 2022, following the ‘cake tank incident’ (坦克蛋糕事件). This incident unfolded during one of his livestreams when Li Jiaqi and his co-host introduced a chocolate cake in the shape of a tank, with an assistant in the back mentioning something about the sound of shooting coming from a tank (“坦克突突”). This livestream took place on June 3rd, on the night before the 33rd anniversary of the crackdown on the Tiananmen protests.

While Li Jiaqi did not directly touch upon a politically sensitive issue with his controversial livestream, his actions were perceived as a disregard for customer loyalty and displayed an arrogance inconsistent with socialist core values. This behavior garnered criticism in a recent post by the state media outlet CCTV.

Post by CCTV condemning Li’s behavior.

Other state media outlets and official channels have joined in responding to the issue, amplifying the narrative of a conflict between the ‘common people’ and the ‘arrogant influencer.’

#3 Striking a Wrong Chord in Challenging Times

Lastly, Li Jiaqi’s controversial livestream moment also became especially big due to the specific words he said about people needing to reflect on their own work efforts if they cannot afford a $11 eyebrow pencil.

Various online discussions and some media, including CNN, are tying the backlash to young unemployment, tepid consumer spending, and the ongoing economic challenges faced by workers in China.

Since recent years, the term nèijuǎn (‘involution’, 内卷) has gained prominence when discussing the frustrations experienced by many young people in China. It serves as a concept to explain the social dynamics of China’s growing middle class who often find themselves stuck in a “rat race”; a highly competitive education and work environment, where everyone is continually intensifying their efforts to outperform one another, leading to this catch 22 situation where everyone appears to be caught in an unending cycle of exertion without substantial progress (read more here).

Weibo commenters note that, given China’s current employment situation and wage levels, hard work is not necessarily awarded with higher income. This context makes Li Jiaqi’s comments seem even more unnecessary and disconnected from the realities faced by his customers. One Shanghai surgeon responded to Li’s comments, saying that the fact that his salary has not increased over the last few year certainly is not because he is not working hard enough (#上海胸外科医生回应李佳琦言论#).

Some observers also recognize that Li, as an e-commerce professional, is, in a way, trapped in the same cycle of “inversion” where brands are continuously driving prices down to such low levels that consumers perceive it as the new normal. However, this pricing strategy may not be sustainable in the long run. (Ironically, some brands currently profiting from the controversy by promoting their own 79 yuan deals, suggesting their deal is much better than Li’s. Among them is the domestic brand Bee & Flower 蜂花, which is offering special skin care products sets for 79 yuan in light of the controversy.)

Many discussions therefore also revolve around the question of whether 79 yuan or $11 can be considered expensive for an eyebrow pencil, and opinions are divided. Some argue that people pay much more for skincare products, while others point out that if you were to weigh the actual quantity of pencil color, its price would surpass that of gold.

The incident has sparked discussions about the significance of 79 yuan in today’s times, under the hashtag “What is 79 yuan to normal people” (#79元对于普通人来说意味着什么#).

People have shared their perspectives, highlighting what this amount means in their daily lives. For some, it represents an entire day’s worth of home-cooked meals for a family. It exceeds the daily wages of certain workers, like street cleaners. Others equate it to the cost of 15 office lunches.

One netizen posts 79 yuan ($10.9) worth of groceries.

Amid all these discussions, it also becomes clear that many people are trying to live a frugal live in a time when their wages are not increasing, and that Li’s comments are just one reason to vent their frustrations about the situation they are in, In those regards, Li’s remarks really come at a wrong time, especially coming from a billionaire.

Will Li be able to continue his career after this?

Some are suggesting that it is time for Li to take some rest, speculating that Li’s behavior might stem from burn-out and mental issues. Others think that Li’s hardcore fans will remain loyal to their e-commerce idol.

For now, Li Jiaqi must tread carefully. He has already lost 1.3 million followers on his Weibo account. What’s even more challenging than regaining those one million followers is rebuilding the trust of his viewers.

Update: On September 19, the Florasis/Huaxizi brand finally apologized for its late response to the controversy, and the brand stated that the controversy provided an opportunity for them to listen to “the voice of their consumers.” Their decision to release a statement seemed fruitful: they gained 20,000 new followers in a night.

By Manya Koetse

with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Jeffreys, Elaine, and Jian Xu. 2023. “Governing China’s Celebrities.” Australian Institute of International Affairs, 18 May https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/governing-chinas-celebrities/ [12 Sep 2023].

Sullivan, Jonathan, and Séagh Kehoe. 2019. “Truth, Good and Beauty: The Politics of Celebrity in China.” The China Quarterly 237 (March): 241–256.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?