China Books & Literature

Nineteen Eighty-Four Turns 70: Orwellian China and Orwell in China

“We still need independent, courageous thinkers like George Orwell. We still need 1984.”

Published

5 years agoon

First published

George Orwell’s classic Nineteen Eighty-Four turned seventy this week. For a country that is labeled ‘Orwellian’ so often, it is perhaps surprising that the modern classic, describing a nightmarish totalitarian state, is well-read within the People’s Republic of China and is not banned from its bookstores.

“Big Brother is Watching You” is the sentence that people around the world have come to know through the novel 1984 or Nineteen Eighty-Four, that turned 70 this week.

Nineteen Eighty-Four is a novel about a nightmare future in the year 1984. It takes place in a totalitarian state where the Party is central to people’s everyday lives and where propaganda, surveillance, misinformation, and manipulation of the past are ubiquitous.

The book revolves around Winston Smith, a citizen of London, Oceania, who works at Minitrue (Ministry of Truth) and who secretly hates the society he lives in with its all-controlling Party, the ‘Big Brother’ leader, and the Thought Police.

Smith is critical of the workings of the Party and the lies it imposes, which then pass into history and become ‘truth’; as the Party slogan goes: “Who controls the past, controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.”

“Orwellian China”

There is probably no other country in the world that has been described as “Orwellian” in English-language media as often as China has over the past few years. According to Google Trends, ‘China’ currently is one of the most related topics people in the US are searching for when they type in the word ‘Orwellian’ on the search engine.

The topic recently most associated with Orwell’s novel is that of China’s Social Credit System. In October of 2018, US Vice President Mike Pence addressed China’s nascent Social Credit System in a speech on China, calling it “an Orwellian system premised on controlling virtually every facet of human life” (Whitehouse.gov).

Since then, George Orwell and Nineteen Eighty-Four have been used more often to describe developments in China.

‘Orwellian’ and ‘China’ come up with more than 28,000 results in Google News alone, the term often being used with any PRC news that relates to technology, government control, and propaganda.

Ironically, many of the news reports addressing ‘Orwellian China’ and its Social Credit System (SCS) are, in the Orwellian tradition, spreading misinformation themselves, conflating different issues or presenting speculation as fact – see some examples of speculative reporting on the SCS in this list.

But also when reporting on China’s growing mass camera surveillance, the Xinjiang internment camps, the launch of the ‘Study Xi, Strengthen China’ [Xuexi Qiangguo] app, or the increasing use of facial recognition, the comparison to George Orwell’s 1949 classic is everywhere in the English language media world today.

一九八四: Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four in China

For a country that is labeled ‘Orwellian’ so often, it is perhaps surprising that Nineteen Eighty-Four is actually not censored or banned in the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

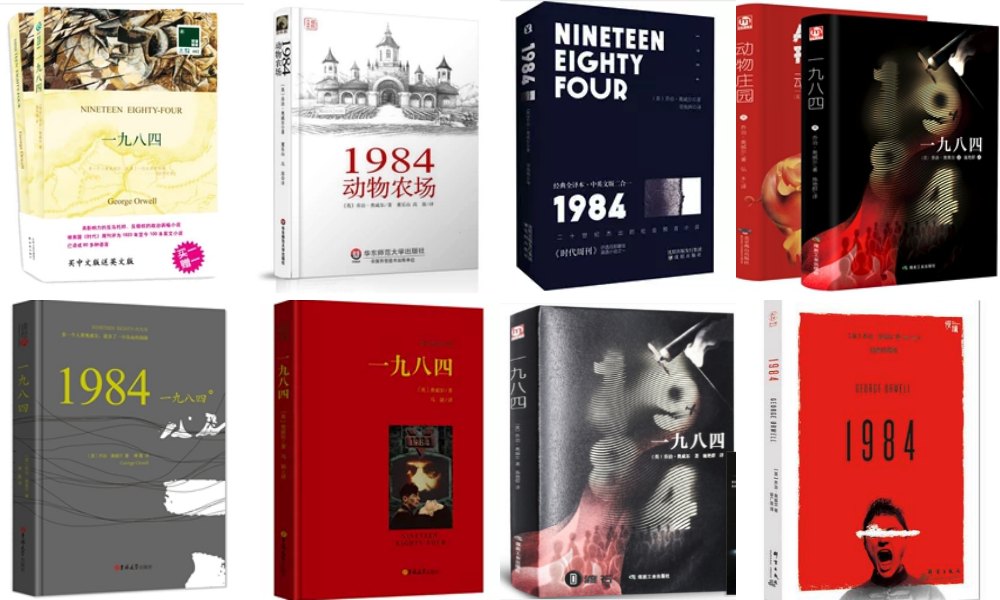

Since the first PRC edition of the novel was published in 1979, it has become a famous and well-read work that is available for purchase in Chinese or English in all big bookstores in Chinese cities or online via e-commerce sites as Taobao.com.

The famous sentence “Big Brother is Watching You” translates to “Lǎo dàgē zài zhùshìzhe nǐ” (“老大哥在注视着你”) in Mandarin, and often pops up on social media, together with terms such as “doublethink” (shuāngchóng sīxiǎng, 双重思想) or “Thought Police” (sīxiǎng jǐngchá 思想警察).

On Douban, an influential web portal that allows users to rate and review books, films, etc, various editions of Nineteen Eighty-Four (most of them translated by Dong Leshan 董乐山) have been rated with a 9.3 or higher by thousands of web users.

Reading 1984, by Weibo user @耀离Pinus.

“I like this book, it’s just a bit too dark for me,” some reviewers write, with others just saying the book is “very scary,” or seeing some resemblance with the classic works of Chinese authors such as Wang Xiaobo or Lu Xun.

WeChat blog Vopoenix recently stressed the importance of Nineteen Eighty-Four, writing that the novel is not anti-socialism per se: “What Orwell really opposes is fascism, totalitarianism, and nationalism (..), what he really supports is political democracy and social justice.”

70 years later, totalitarianism still has not disappeared, the blog writes: “(..) instead, it has evolved with the times in a more secret way (..). We still need independent, keen and courageous thinkers like George Orwell. We still need 1984.”

One Douban reviewer writes about their thoughts after reading Nineteen Eighty-Four, saying: “What scares me is that sometimes people will ridicule North Korea for being so shut off from the world, but what about us? We’re like frogs at the bottom of a well, but the scary thing is, we don’t even know we’re in the well.”

“Just a work of fiction to Chinese”?

Public sentiments about the 70-year-old Nineteen Eighty-Four novel bearing a resemblance to (present-day) China are seemingly growing stronger on Chinese social media recently. The book appears in online comments and discussions on a daily basis.

“I finished reading the book today,” one Weibo commenter writes: “The biggest thought I had is: this book is very suitable for Chinese people to read.”

“I can now imagine what those ten years were like,” one Douban user posts, referring to the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

“Nineteen Eighty-Four is the first satirical book I’ve read that comes close to the situation in China. If you read it, you’ll know what I mean,” another reader writes.

Different from English-language (social) media, Chinese commenters are not mentioning the book in relation to the country’s Social Credit System at all, but in relation to the heightened censorship that China has recently been seeing in light of the China-US trade war, the Tiananmen anniversary, and the Hong Kong protests.

One Weibo blogger writing a critique about the growing “bizarreness” of the “elephant in the room” (referring to all those big China-related issues that cannot be discussed on social media due to censorship) attracted the attention of Chinese netizens earlier this week (see the full translation of post here).

Many commenters spoke about the Weibo post in relation to Nineteen Eighty-Four, especially when the post addressing the censorship was censored itself.

Some commenters are speculating that Orwell’s novel might one day be banned in China.

Others also wrote that it seemed “like a miracle” that the book was not banned in China, and some suggested it might still happen in the future.

“It will be forbidden very soon,” one Weibo commenter speculates.

“The future is becoming more difficult, really,” one netizen recently wrote: “It’s nearing 1984 (一九八四), and [we] might not be able to see it later.”

But, in Chinese online media, Nineteen Eighty-Four is by no means only mentioned in relation to China. There are also those blogs or news articles that mention the Orwellian aspects of the story of Edward Snowden, or connect Orwell to Trump’s America.

In late 2018, state tabloid Global Times denounced the ubiquitous Western media reports on “Orwellian China.” Author Yu Jincui wrote:

“Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is a classic to Westerners, but it is just a work of fiction to Chinese and they are fed up with Orwellian style preaching from Western elites. This kind of conversation will lead nowhere.”

But many netizens do not agree with the fictional part. “Nineteen Eighty-Four is not a work of fiction, it is a record of our future,” one Weibo user writes.

“Is Big Brother watching me?” others wonder.

“The first time I read it, I just read it,” another Douban user says: “The second time I read it, I really started to understand. Here’s to George Orwell!”

Despite all speculation on social media, there are no indications that Nineteen Eighty-Four will be banned from China any time soon.

For now, even 70 years after its first publication and 40 years after its first Chinese translation, readers in the People’s Republic can continue to devour and discuss Orwell’s classic work and the mirror it holds up to present-day China, America, Europe, and the world today.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

PS: Some recommended reading on Social Credit in English:

* Creemers, Rogier. 2018. “China’s Social Credit System: An Evolving Practice of Control.”May 9. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3175792.

* Dai, Xin. 2018. “Toward a Reputation State: The Social Credit System Project of China.” June 10, available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3193577 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3193577.

* Daum, Jeremy. 2017. “China through a glass, darkly.” China Law Translate, Dec 24 https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/seeing-chinese-social-credit-through-a-glass-darkly/?lang=en [24.5.18].

* Daum, Jeremy. 2017. “Giving Credit 2: Carrots and Sticks.” China Law Translate, Dec 15 https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/giving-credit-2-carrots-and-sticks/?lang=en [27.5.18].

* Horsley, Jamie. 2018. “China’s Orwellian Social Credit Score Isn’t Real.” Foreign Policy, Nov 16 https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/11/16/chinas-orwellian-social-credit-score-isnt-real/ [10.6.19].

* Koetse, Manya. 2018. “Insights into the Social Credit System on Chinese Online Media vs Its Portrayal in Western Media.” What’s on Weibo, Oct 30 https://www.whatsonweibo.com/insights-into-the-social-credit-system-on-chinese-online-media-and-stark-contrasts-to-western-media-approaches/

* Koetse, Manya. 2018. “Open Sesame: Social Credit in China as Gate to Punitive Measures and Personal Perks.” What’s on Weibo, May 27 https://www.whatsonweibo.com/open-sesame-social-credit-in-china-as-gate-to-punitive-measures-and-personal-perks/.

* Kostka, Genia. 2018. “China’s Social Credit Systems and Public Opinion: Explaining High Levels of Approval” SSRN, July 23. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3215138 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3215138 [29.10.18].

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Books & Literature

Why Chinese Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Shopping Festival

Bookworms love to get a good deal on books, but when the deals are too good, it can actually harm the publishing industry.

Published

2 months agoon

June 8, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

JD.com’s 618 shopping festival is driving down book prices to such an extent that it has prompted a boycott by Chinese publishers, who are concerned about the financial sustainability of their industry.

When June begins, promotional campaigns for China’s 618 Online Shopping Festival suddenly appear everywhere—it’s hard to ignore.

The 618 Festival is a product of China’s booming e-commerce culture. Taking place annually on June 18th, it is China’s largest mid-year shopping carnival. While Alibaba’s “Singles’ Day” shopping festival has been taking place on November 11th since 2009, the 618 Festival was launched by another Chinese e-commerce giant, JD.com (京东), to celebrate the company’s anniversary, boost its sales, and increase its brand value.

By now, other e-commerce platforms such as Taobao and Pinduoduo have joined the 618 Festival, and it has turned into another major nationwide shopping spree event.

For many book lovers in China, 618 has become the perfect opportunity to stock up on books. In previous years, e-commerce platforms like JD.com and Dangdang (当当) would roll out tempting offers during the festival, such as “300 RMB ($41) off for every 500 RMB ($69) spent” or “50 RMB ($7) off for every 100 RMB ($13.8) spent.”

Starting in May, about a month before 618, the largest bookworm community group on the Douban platform, nicknamed “Buying Like Landsliding, Reading Like Silk Spinning” (买书如山倒,看书如抽丝), would start buzzing with activity, discussing book sales, comparing shopping lists, or sharing views about different issues.

Social media users share lists of which books to buy during the 618 shopping festivities.

This year, however, the mood within the group was different. Many members posted that before the 618 season began, books from various publishers were suddenly taken down from e-commerce platforms, disappearing from their online shopping carts. This unusual occurrence sparked discussions among book lovers, with speculations arising about a potential conflict between Chinese publishers and e-commerce platforms.

A joint statement posted in May provided clarity. According to Chinese media outlet The Paper (@澎湃新闻), eight publishers in Beijing and the Shanghai Publishing and Distribution Association, which represent 46 publishing units in Shanghai, issued a statement indicating they refuse to participate in this year’s 618 promotional campaign as proposed by JD.com.

The collective industry boycott has a clear motivation: during JD’s 618 promotional campaign, which offers all books at steep discounts (e.g., 60-70% off) for eight days, publishers lose money on each book sold. Meanwhile, JD.com continues to profit by forcing publishers to sell books at significantly reduced prices (e.g., 80% off). For many publishers, it is simply not sustainable to sell books at 20% of the original price.

One person who has openly spoken out against JD.com’s practices is Shen Haobo (沈浩波), founder and CEO of Chinese book publisher Motie Group (磨铁集团). Shen shared a post on WeChat Moments on May 31st, stating that Motie has completely stopped shipping to JD.com as it opposes the company’s low-price promotions. Shen said it felt like JD.com is “repeatedly rubbing our faces into the ground.”

Nevertheless, many netizens expressed confusion over the situation. Under the hashtag topic “Multiple Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Book Promotions” (#多家出版社抵制618图书大促#), people complained about the relatively high cost of physical books.

With a single legitimate copy often costing 50-60 RMB ($7-$8.3), and children’s books often costing much more, many Chinese readers can only afford to buy books during big sales. They question the justification for these rising prices, as books used to be much more affordable.

Book blogger TaoLangGe (@陶朗歌) argues that for ordinary readers in China, the removal of discounted books is not good news. As consumers, most people are not concerned with the “life and death of the publishing industry” and naturally prefer cheaper books.

However, industry insiders argue that a “price war” on books may not truly benefit buyers in the end, as it is actually driving up the prices as a forced response to the frequent discount promotions by e-commerce platforms.

China News (@中国新闻网) interviewed publisher San Shi (三石), who noted that people’s expectations of book prices can be easily influenced by promotional activities, leading to a subconscious belief that purchasing books at such low prices is normal. Publishers, therefore, feel compelled to reduce costs and adopt price competition to attract buyers. However, the space for cost reduction in paper and printing is limited.

Eventually, this pressure could affect the quality and layout of books, including their binding, design, and editing. In the long run, if a vicious cycle develops, it would be detrimental to the production and publication of high-quality books, ultimately disappointing book lovers who will struggle to find the books they want, in the format they prefer.

This debate temporarily resolved with JD.com’s compromise. According to The Paper, JD.com has started to abandon its previous strategy of offering extreme discounts across all book categories. Publishers now have a certain degree of autonomy, able to decide the types of books and discount rates for platform promotions.

While most previously delisted books have returned for sale, JD.com’s silence on their official social media channels leaves people worried about the future of China’s publishing industry in an era dominated by e-commerce platforms, especially at a time when online shops and livestreamers keep competing over who has the best book deals, hyping up promotional campaigns like ‘9.9 RMB ($1.4) per book with free shipping’ to ‘1 RMB ($0.15) books.’

This year’s developments surrounding the publishing industry and 618 has led to some discussions that have created more awareness among Chinese consumers about the true price of books. “I was planning to bulk buy books this year,” one commenter wrote: “But then I looked at my bookshelf and saw that some of last year’s books haven’t even been unwrapped yet.”

Another commenter wrote: “Although I’m just an ordinary reader, I still feel very sad about this situation. It’s reasonable to say that lower prices are good for readers, but what I see is an unfavorable outlook for publishers and the book market. If this continues, no one will want to work in this industry, and for readers who do not like e-books and only prefer physical books, this is definitely not a good thing at all!”

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Books & Literature

The Many Books Lost in the China Floods: Catastrophic Flooding Hits Zhuozhou’s Publishing Industry

After Typhoon Doksuri, some major warehouses in Zhuozhou have seen their depots transform into a sea of floating books.

Published

12 months agoon

August 2, 2023

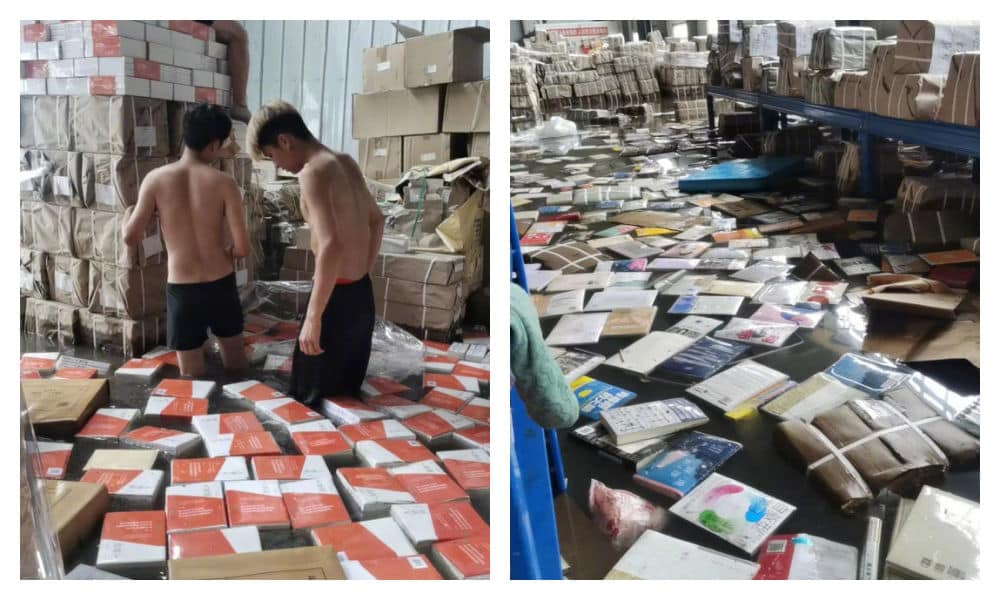

Dozens of prominent Chinese publishing companies and book warehouses based in Hebei’s Zhuozhou, a major hub for the publishing industry, have witnessed their book depots destroyed as water levels surged as high as the second floor. Distribution will be at a standstill for at least 15 days.

Zhuozhou (涿州) is a county-level city in Baoding, Hebei Province, known as a major hub for the Chinese publishing industry. It is one of the areas that has been badly affected by the heavy rainfall and flash floodings China has seen this week, after Typhoon Doksuri moved from the Philippines to Taiwan toward Beijing and surrounding regions in mainland China.

In Zhuozhou, dozens of publishing warehouses were affected by floods and water damage due to the storm, resulting in losses amounting to hundreds of millions of yuan. Zhuozhou’s print media industry is closely linked with the center of China’s publishing industry in Beijing, just 25 miles away.

Some warehouses, such as that of Beijing China Media Times, are as large as 8000 square meters, housing over three million books. According to Sina News, one area that housed around 200 publishing companies was almost entirely flooded.

A Weibo post by the Hong Kong Ta Kung Wen Wei Media Group (HKTKWW, @大公文匯網) showed the status quo at some warehouses, which had changed into a sea of books.

Posted on Weibo by HKTKWW, @大公文匯網, the situation at the Beijing China Media Times book warehouse in Zhuozhou.

Posted on Weibo by HKTKWW, @大公文匯網, the situation at the Beijing China Media Times book warehouse in Zhuozhou.

Publisher Books China (中图网), known as an industry “outlet store” for selling discounted and out-of-print books, also saw its central Zhuozhou warehouse completely flooded.

Around 100 of their staff members remained trapped at the office on Tuesday night without any food, drinks, or blankets, while water levels continued to rise. An additional cause for concern was the strong odor emanating from a nearby adhesive tape factory. Some employees suspected that toxic gases might have leaked, leading to several of them feeling unwell and vomiting after exposure.

According to China News (@中国新闻网), all employees were safely evacuated on Wednesday.

Photo posted on Weibo by China News (@中国新闻网), showing how the Books China (中图网) major warehouse was severely impacted by the recent floods, with water levels rising up to the second floor.

In an interview with Chinese newspaper Southern Weekend (南方周末), Beijing China Media Times CEO Ran Zijian (冉子健) revealed that his company had not received any advance warning about the heavy rains and the possibility of flooding, despite the area being prone to floods due to its low-lying terrains. All of the company’s 3.6 million books are now submerged underwater.

Photos provided to Southern Weekend, Weibo.

The water levels rose so rapidly on Tuesday that there was hardly any time to rescue the books, making the evacuation of staff members the first priority. Bookseller Zou Bin (邹斌) told Southern Weekend that he saw the water levels rising so fast in his 5,000 square meter warehouse that he basically witnessed “25 million yuan [$3.5 million] disappear in an hour, powerless to do anything about it.”

According to several Chinese news outlets, the distribution and dispatching of books will be impossible for numerous publishing houses based in Zhuozhou for at least the next 15 days. As the local book industry continues to assess the damages, it remains uncertain how severely the companies have been affected at this stage. For some, it feels like they are starting from scratch all over again.

But most netizens emphasize that it’s more important that employees are safe, as people’s lives are more important than paper books. “Who cares about dispatching books at this time?” some commenters wonder, while others express grief about all the books lost, saying, “It’s just such a pity.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

Ed Sander

June 12, 2019 at 8:17 pm

It’s really not that strange that the book isn’t banned in China, since it was never written with China in mind. Orwell wrote 1984 imagining a war-time Great Britain ruled by Stalin. It was written in a time before the Communists seized power and founded the PRC and way before the Cultural Revolution.

Having said that, the opposite, that 1984 at times eerily similar to China, is definitely true. As a matter of fact, when my Chinese wife saw the movie for the first time and watched the scene with Winston Smith changing news articles she muttered ‘shit … this is just like China’. And I hadn’t given her any leads before watching the film.

Still, the term Orwellian is sometimes appropriate when used in combination with China (think Xinjiang, censorship and the all powerful rules that bestows fear in everybody) but unnecessary in other cases like the social credit system, which is a lot more mundane than most mass media might have you believe.