China Insight

Explainer: Answering Five Big Questions on the ‘Study Xi’ App

Published

5 years agoon

First published

As the ‘Study Xi’ app, that encourages China’s online population to study Xi Jinping Thought, keeps on dominating China’s top app charts, these are some of the big questions on China’s latest interactive propaganda tool. What’s on Weibo explains.

Since its launch in January of this year, the ‘Study Xi, Strengthen China’ app (Xué Xí Qiáng Guó 学习强国, also ‘Study Xi, Strong Country’)1, that was released by the CCP Central Propaganda Research Center (中央宣传部宣传舆情研究中心), has been making headlines both in and outside of China.

The app, that revolves around studying “Xi Jinping’s Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” (习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想), is still top ranking on China’s popular app charts: it is the overall second top free app in the Chinese iOS Store, and the number one most popular educational app in Chinese charts at the time of writing.

‘Study Xi’ is a multi-functional educational platform that offers users various ways to study Xi Jinping Thought, Party history, Chinese culture, history, and much more. Once people are registered on the app, they can also access the platform via PC. Every user has a score that will go up depending on how active they are on the app.

An important part of the app is its news feed: the home page features “recommended” reads that all focus on Xi Jinping and the Party. Another major feature is its ‘quiz’ page: every week, there are different quizzes that users can do, relating to all sorts of things, from Party ideology to famous Chinese poems.

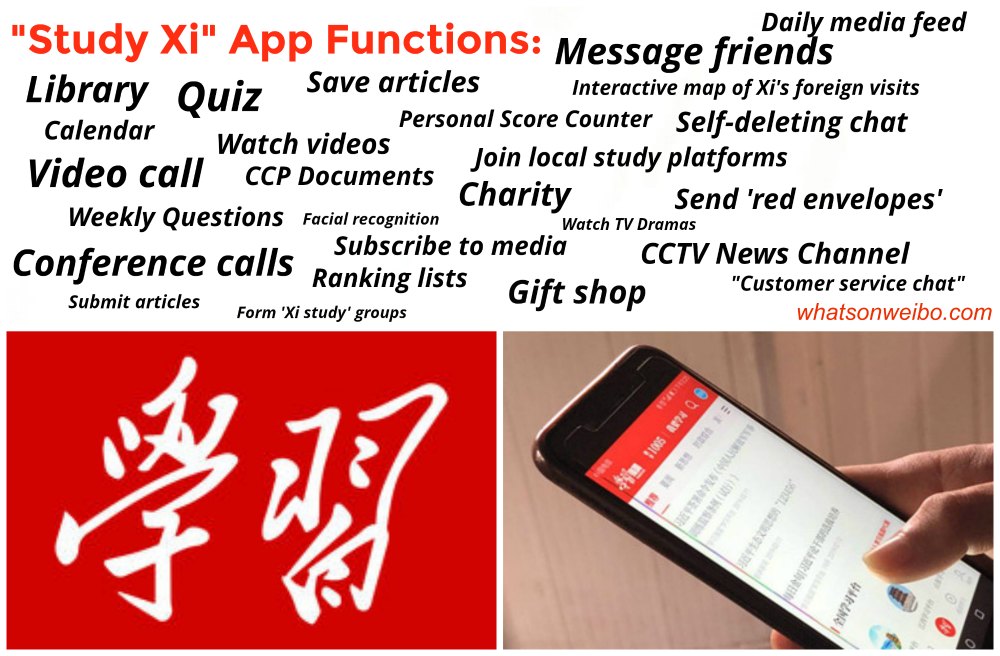

For our previous article on the app, we listed some of its functions in the image below. It is much more than a media app alone; it also has a social function, that allows users to connect with friends, message them, call them, and even send them ‘red envelopes’ (money presents).

As its popularity continues, and Weibo discussions on the app continue, we will answer some of the questions you might have about the app in this article.

#1 Was the app developed by Alibaba?

Ever since its launch, it has been rumored that Alibaba is the company that developed this app. In the app’s descriptions, however, all copyright and credits go to the Central Propaganda Department of the Communist Party that has allegedly started developing this app since November of 2017. Nowhere does it say that Alibaba was involved in its development.

Alibaba’s involvement, however, is in no way a secret: the app’s ‘red envelope’ function is made possible through Alipay, the online payment platform that is owned by Ant Financial Services Group, an affiliate company of the Chinese Alibaba Group. One way for users to verify their identity on the app is also by linking it to their Alipay account.

Users of the app also noted that, upon registering for the app, their old Ding Ding conversations were automatically loaded into their chat history. Others said that upon changing their Ding Ding password, their Study Xi password was automatically also changed. Ding Ding is a multifunctional enterprise messaging app by Alibaba (read here), and many of its functions are also incorporated in the Study Xi app.

“I just discovered Study Xi is based on the Ding Ding app – all conversations I had with a good friend on Ding Ding are also displayed on the Study Xi app,” one of the many Weibo comments on the topic said: “Have other people found out yet that the user information between Study Xi and Ding Ding are interoperating with each other?”

According to a Reuters article from February of this year, sources confirmed that the ‘Study Xi, Strengthen China’ app was indeed developed by a special projects team at Alibaba known as the ‘Y Projects Business Unit’ (Y项目事业部). In 2018, Alibaba also published job positions on its website for this ‘Y Projects Business Unit,’ in which the offered jobs would entail working on an “educational platform.”

#2 Is ‘Study Xi’ mandatory?

Various English-language media covering the Study Xi app have called it a “mandatory app,” but it is not true that all Chinese mobile phone users are required to download it.

Local training for the Study Xi app, image by @高淳固城街道 (March 14, 2019).

Party members, however, are strongly encouraged to use the app to learn more about Party ideology, new policies, and political theory.

All over the country, there are local Party meetings where Party members are taught how to download and use the app. Local state media Weibo accounts frequently post about these meetings, with some mentioning that they are organized as ordered by “higher authorities” (“按照上级有关要求” or “按照要求”), suggesting that organizing and/or attending these classes and downloading the app is indeed mandatory for Party members.

A ‘Study Xi’ meeting in Debao county in Baise, Guangxi. Image via Xinhua.

Many Chinese (state-owned) companies and schools have also ordered their employees and students to download the app. Some Weibo users write that their school requires them to score a certain number of points per day on the app.

“A lot of people I know now use the ‘Study Xi, Strengthen China’ app, but it’s not the same everywhere, as it is required to score a certain number of points in some places. This work method will even make people dislike good things. Studying should be conscious and voluntary,” one Weibo blogger wrote in March.

“I used to like the app because there’s news on current politics and there are quizzes, but since my work unit requested us to spend 30 minutes per day on it, I started to find it annoying,” one netizen (@超凶的钢丝球) said.

“The leader of my mum’s factory had all the workers download the ‘Study Xi, Strengthen China’ app – this world has gone crazy,” another commenter wrote.

“How can they force us to score 30 points per day?” one Weibo commenter wrote: “I’m happy they canceled the rankings. This should not be mandatory.”

The ‘ranking system’ this netizen refers to, was a function in the app that allowed users to view the scores of other users and friends. In late March, nearly three months after the app was launched, its ranking feature was canceled. This means that users can no longer view other people’s score and ‘compete’ with them. The maximum score per day was also reduced from 66 points to 52 points.

Many people on Weibo expressed that they were happy that the ranking system was canceled since they allegedly suffered from peer pressure to reach a certain score. But there are also those who say they found the ranking system “motivational,” and write they are disappointed their scores are now private. “We can always still share our scores on social media,” one Weibo user suggested.

#3 How does the scoring system work?

The scoring system of the ‘Study Xi’ app works as follows:

- Upon registering for the app, you receive 1 point.

- For every article or essay one reads, you get 1 point (one per article, does not work with articles that have already been viewed before, maximum 6 points per day).

- For every video you watch you get 1 point (the same video won’t be credited with an extra point if you see it twice, max 6 points per day).

- The time you spend on the app is also rewarded with points: for every 2 minutes of reading an essay, you get 1 point (max 6 points per day).

- For every 5 minutes of watching a video, you get 1 point (max 8 points per day).

- You get 1 point for “subscribing” to a media account, which will then show up in your news feed.

- If you share two articles with friends, you get 1 point.

- You get 1 point for every two articles or essays you ‘save’ within the app.

- If you score 100% on a quiz, you get 10 points.

The app encourages users to ‘Study Xi’ at particular times of the day. The morning 6:00-8:30 timeframe, along with the 12:00-14:00 slot and evening 20:00-22:30 times, are designated as so-called “active time slots” during which users can score double points for their activities. Within these time slots, reading an article would, for example, grant a user 2 points instead of 1.

This signals that, in line with good working morale, people are supposed to look into the app during their morning commute, their lunch break, and before bedtime, and are indirectly discouraged from using it during (office) working hours.

The points that are scored on the app will be valid for two years.

Those who accumulate enough points can exchange them for gifts, such as study books or dictionaries, cinema tickets, or other items, which will then be sent to their home address.

Recently, more places also offer special discounts for people with a high Study Xi score. In those regards, the score system is somewhat similar to Alibaba’s Sesame Credit score, that also allows people with high scores certain benefits.

This month, various scenic spots across China’s Henan province offer people with a score of 1000 or higher free entrance to their sites. Those with 1000 points, for example, get one free entrance ticket to the Zhengzhou Fuxi Mountain scenic spot; those who have 2500 points get five tickets for free.

Another recent example is that ‘Study Xi’ users can now get a discount on tickets for the ballet show Bright Red Star.

#4 Is the app the Little Red Book ‘2.0’?

Foreign media have described the ‘Study Xi’ app as a “high-tech equivalent of Mao’s Little Red Book,” but to what extent is it really?

There is, of course, no straightforward answer here. The Little Red Book and the ‘Study Xi’ app are very different in many ways. The Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong book was first published in 1964 and fully focused on selected quotations by the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party. More than a book, it became a symbol of the Cultural Revolution and was a talisman for many (also see Mao’s Little Red Book: A Global History).

The ‘Study Xi’ app is not a singular text and goes much further than Xi alone; it has an online database containing texts and videos from dozens of sources and is a platform that allows users to educate themselves on various topics, from architecture to biology and much more.

But one thing to keep in mind is that both the Little Red Book and the ‘Study Xi’ app are propaganda methods that communicate a strong message through a medium that can be easily placed in many locations, reaching a great number of people. They both revolve around their Communist leaders, turning them into political idols, and literally brings Party ideology within a hand’s reach.

By turning the ‘Study Xi’ platform into an app that people can also show at various places to get free tickets, based on their score, they are also turning the app into something that matters in the public domain.

#5 How is the app received by Chinese internet users?

Online responses to the app have been somewhat mixed ever since it came out. For the past months, we’ve been consistently checking online responses to the app. “It’s the app that Party members dread, and non-Party members love” is a comment that popped up on Weibo recently, and it seems to cover a general sentiment: many people appreciate the app, but when it is required of them to use it an to score a certain number of points, they start to dread it.

One popular history blogger (@豢龙有道) recently praised the app on Weibo, saying they had previously not thought of downloading it because they are not a Party member, but now discovered the rich educational sources the app offers. That post was shared over 45,000 times.

The hashtag “‘Study Xi, Strengthen China’ is a treasure app” (#学习强国是个宝藏app#) has been viewed over 180 million times on Weibo, with thousands of commenters applauding the app; they mostly seem to praise its many online educational sources, which include MOOC (Massive Open Online Courses) on dozens of subjects, and its online ad-free library of movies, TV dramas, and documentaries.

One general sentiment that most people seem to agree on is that the app is “not bad at all” in how it has been developed and the sources it offers.

In this day and age, Chinese internet users can choose from thousands of different media apps, TV channels, newspapers, and magazines. For the Central Propaganda Department to develop a product that is now being used by millions of people across the country who think it is “not bad at all,” is perhaps really not bad at all.

Also read:

* Gamifying Propaganda: Everything You Need to Know about China’s ‘Study Xi’ App

* Here’s Xi the Cartoon – Online Animations Are China’s New ‘Propaganda Posters’

* Top 5 Most Popular Study and Educational Apps in China

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

1Translation suggested by Helen Wang @helanwanglondon.

Directly support Manya Koetse. By supporting this author you make future articles possible and help the maintenance and independence of this site. Donate directly through Paypal here. Also check out the What’s on Weibo donations page for donations through creditcard & WeChat and for more information.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Insight

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

The story of ‘Fat Cat’ has become a hot topic in China, sparking widespread sympathy and discussions online.

Published

3 months agoon

May 9, 2024

The tragic story behind the recent suicide of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ has become a major topic of discussion on Chinese social media, touching upon broader societal issues from unfair gender dynamics to businesses taking advantage of grieving internet users.

The story of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer from Hunan who committed suicide has gone completely viral on Weibo and beyond this week, generating many discussions.

In late April of this year, the young man nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ (胖猫 Pàng Māo, literally fat or chubby cat), tragically ended his life by jumping into the river near the Chongqing Yangtze River Bridge (重庆长江大桥) following a breakup with his girlfriend. By now, the incident has come to be known as the “Fat Cat Jumping Into the River Incident” (胖猫跳江事件).

News of his suicide soon made its rounds on the internet, and some bloggers started looking into what was behind the story. The man’s sister also spoke out through online channels, and numerous chat records between the young man and his girlfriend emerged online.

One aspect of his story that gained traction in early May is the revelation that the man had invested all his resources into the relationship. Allegedly, he made significant financial sacrifices, giving his girlfriend over 510,000 RMB (approximately 71,000 USD) throughout their relationship, in a time frame of two years.

When his girlfriend ended the relationship, despite all of his efforts, he was devastated and took his own life.

The story was picked up by various Chinese media outlets, and prominent social and political commentator Hu Xijin also wrote a post about Fat Cat, stating the sad story had made him tear up.

As the news spread, it sparked a multitude of hashtags on Weibo, with thousands of netizens pouring out their thoughts and emotions in response to the story.

Playing Games for Love

The main part of this story that is triggering online discussions is how ‘Fat Cat,’ a young man who possessed virtually nothing, managed to provide his girlfriend, who was six years older, with such a significant amount of money – and why he was willing to sacrifice so much in order to do so.

The young man reportedly was able to make money by playing video games, specifically by being a so-called ‘booster’ by playing with others and helping them get to a higher level in multiplayer online battle games.

According to his sister, he started working as a ‘professional’ video gamer as a means of generating money to satisfy his girlfriend, who allegedly always demanded more.

He registered a total of 36 accounts to receive orders to play online games, making 20 yuan per game (about $2.80). Because this consumed all of his time, he barely went out anymore and his social life was dead.

In order to save more money, he tried to keep his own expenses as low as possible, and would only get takeout food for himself for no more than 10 yuan ($1,4). His online avatar was an image of a cat saying “I don’t want to eat vegetables, I want to eat McDonald’s.”

The woman in question who he made so many sacrifices for is named Tan Zhu (谭竹), and she soon became the topic of public scrutiny. In one screenshot of a chat conversation between Tan and her boyfriend that leaked online, she claimed she needed money for various things. The two had agreed to get married later in this year.

Despite of this, she still broke up with him, driving him to jump off the bridge after transferring his remaining 66,000 RMB (9135 USD) to Tan Zhu.

As the story fermented online, Tan Zhu also shared her side of the story. She claimed that she had met ‘Fat Cat’ over two years ago through online gaming and had started a long distance relationship with him. They had actually only met up twice before he moved to Chongqing. She emphasized that financial gain was never a motivating factor in their relationship.

Tan additionally asserted that she had previously repaid 130,000 RMB (18,000 USD) to him and that they had reached a settlement agreement shortly before his tragic death.

Ordering Take-Out to Mourn Fat Cat

– “I hope you rest in peace.”

– “Little fat cat, I hope you’ll be less foolish in your next life.”

– “In your next life, love yourself first.”

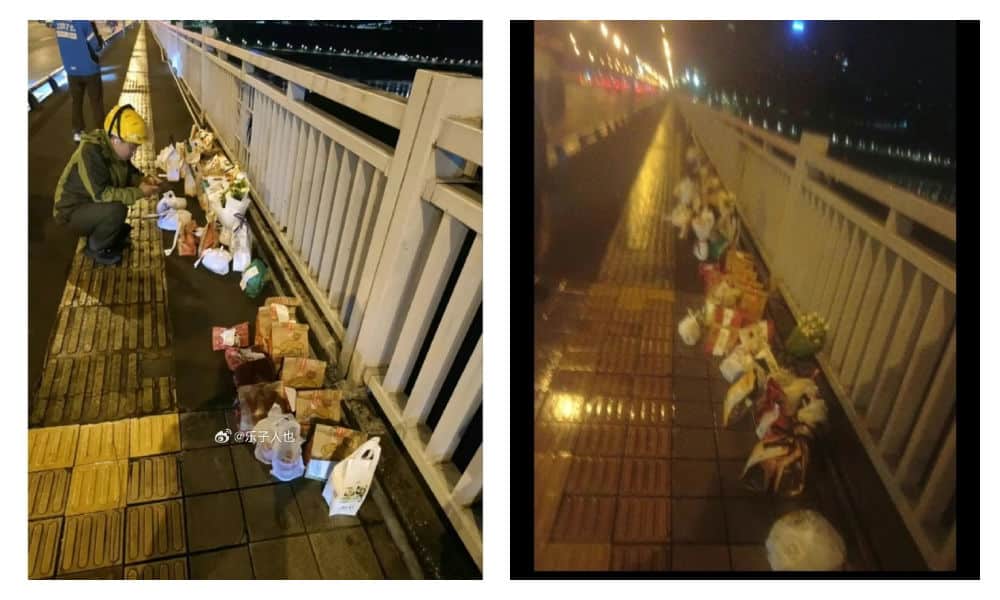

These are just a few of the messages left by netizens on notes attached to takeout food deliveries near the Chongqing Yangtze River Bridge.

AI-generated image spread on Chinese social media in connection to the event.

As Fat Cat’s story stirred up significant online discussion, with many expressing sympathy for the young man who rarely indulged in spending on food and drinks, some internet users took the step of ordering McDonalds and other food delivery services to the bridge, where he tragically jumped from, in his honor.

This soon snowballed into more people ordering food and drinks to the bridge, resulting in a constant flow of delivery staff and a pile-up of take-out bags.

Delivery food on the bridge, photo via Weibo.

However, as the food delivery efforts picked up pace, it came to light that some of the deliveries ordered and paid for were either empty or contained something different; certain restaurants, aware of the collective effort to honor the young man, deliberately left the food boxes empty or substituted sodas or tea with tap water.

At least five restaurants were caught not delivering the actual orders. Chinese bubble tea shop ChaPanda was exposed for substituting water for milk tea in their cups. On May 3rd, ChaPanda responded that they had fired the responsible employee.

Another store, the Zhu Xiaoxiao Luosifen (朱小小螺蛳粉), responded on that they had temporarily closed the shop in question to deal with the issue. Chinese fast food chain NewYobo (牛约堡) also acknowledged that at least twenty orders they received were incomplete.

Fast food company Wallace (华莱士) responded to the controversy by stating they had dismissed the employees involved. Mixue Ice Cream & Tea (蜜雪冰城) issued an apology and temporarily closed one of their stores implicated in delivering empty orders.

In the midst of all the controversy, Fat Cat’s sister asked internet users to refrain from ordering take-out food as a means of mourning and honoring her brother.

Nevertheless, take-out food and flowers continued to accumulate near the bridge, prompting local authorities to think of ways of how to deal with this unique method of honoring the deceased gamer.

Gamer Boy Meets Girl

On Chinese social media, this story has also become a topic of debate in the context of gender dynamics and social inequality.

There are some male bloggers who are angry with Tan Zhu, suggesting her behaviour is an example of everything that’s supposedly “wrong” with Chinese women in this day and age.

Others place blame on Fat Cat for believing that he could buy love and maintain a relationship through financial means. This irked some feminist bloggers, who see it as a chauvinistic attitude towards women.

A main, recurring idea in these discussions is that young Chinese men such as Fat Cat, who are at the low end of the social ladder, are actually particularly vulnerable in a fiercely competitive society. Here, a gender imbalance and surplus of unmarried men make it easier for women to potentially exploit those desperate for companionship.

The story of Fat Cat brings back memories of ‘Mo Cha Official,’ a not-so-famous blogger who gained posthumous fame in 2021 when details of his unhappy life surfaced online.

Likewise, the tragic tale of WePhone founder Su Xiangmao (苏享茂) resurfaces. In 2017, the 37-year-old IT entrepreneur from Beijing took his own life, leaving behind a note alleging blackmail by his 29-year-old ex-wife, who demanded 10 million RMB (±1.5 million USD) (read story).

Another aspect of this viral story that is mentioned by netizens is how it gained so much attention during the Chinese May holidays, coinciding with the tragic news of the southern China highway collapse in Guangdong. That major incident resulted in the deaths of at least 48 people, and triggered questions over road safety and flawed construction designs. Some speculate that the prominence given to the Fat Cat story on trending topic lists may have been a deliberate attempt to divert attention away from this incident.

‘Fat Cat’ was cremated. His family stated their intention to take necessary legal steps to recover the money from his former girlfriend, but Tan Zhu reportedly already reached an agreement with the father and settled the case. Nevertheless, the case continues to generate discussions online, with some people wondering: “Is it over yet? Can we talk about something different now?”

Fat Cat images projected in Times Square

However, given that images of the ‘Fat Cat’ avatar have even appeared in Times Square in New York by now (Chinese internet users projected it on one of the big LED screens), it’s likely that this story will be remembered and talked about for some time to come.

UPDATE MAY 25

On May 20, local authorities issued a lengthy report to clarify the timeline of events and details surrounding the death of “Fat Cat,” which had attracted significant attention across China.

The report concluded that there was no fraud involved and that “Fat Cat” and his girlfriend were in a genuine relationship. Tan did not deceive “Fat Cat” for money; the transfers were voluntary. Furthermore, Tan returned most of the money to his parents.

The gamer’s sister is reportedly still being investigated for potentially infringing on Tan’s privacy by disclosing numerous private details to the public.

In the end, one thing is clear in this gamer’s tragic story, which is that there are no winners.

By Manya Koetse

– With contributions by Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy.

Published

3 months agoon

May 3, 2024

It seemed like such a good idea. For this year’s World Book Day, Chinese tea brand LELECHA (乐乐茶) put a spotlight on Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881-1936), one of the most celebrated Chinese authors the 20th century and turned him into the the ‘brand ambassador’ of their special new “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙) milk tea.

LELECHA is a Chinese chain specializing in new-style tea beverages, including bubble tea and fruit tea. It debuted in Shanghai in 2016, and since then, it has expanded rapidly, opening dozens of new stores not only in Shanghai but also in other major cities across China.

Starting on April 23, not only did the LELECHA ‘Smoky Oolong” paper cups feature Lu Xun’s portrait, but also other promotional materials by LELECHA, such as menus and paper bags, accompanied by the slogan: “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” (“老烟腔,新青年”). The marketing campaign was a joint collaboration between LELECHA and publishing house Yilin Press.

Lu Xun featured on LELECHA products, image via Netease.

The slogan “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” is a play on the Chinese magazine ‘New Youth’ or ‘La Jeunesse’ (新青年), the influential literary magazine in which Lu’s famous short story, “Diary of a Madman,” was published in 1918.

The design of the tea featuring Lu Xun’s image, its colors, and painting style also pay homage to the era in which Lu Xun rose to prominence.

Lu Xun (pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a leading figure within China’s May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1915-24) is also referred to as the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance. It was the cultural revolution brought about by the political demonstrations on the fourth of May 1919 when citizens and students in Beijing paraded the streets to protest decisions made at the post-World War I Versailles Conference and called for the destruction of traditional culture[1].

In this historical context, Lu Xun emerged as a significant cultural figure, renowned for his critical and enlightened perspectives on Chinese society.

To this day, Lu Xun remains a highly respected figure. In the post-Mao era, some critics felt that Lu Xun was actually revered a bit too much, and called for efforts to ‘demystify’ him. In 1979, for example, writer Mao Dun called for a halt to the movement to turn Lu Xun into “a god-like figure”[2].

Perhaps LELECHA’s marketing team figured they could not go wrong by creating a milk tea product around China’s beloved Lu Xun. But for various reasons, the marketing campaign backfired, landing LELECHA in hot water. The topic went trending on Chinese social media, where many criticized the tea company.

Commodification of ‘Marxist’ Lu Xun

The first issue with LELECHA’s Lu Xun campaign is a legal one. It seems the tea chain used Lu Xun’s portrait without permission. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s great-grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation, quickly demanded an end to the unauthorized use of Lu Xun’s image on tea cups and other merchandise. He even hired a law firm to take legal action against the campaign.

Others noted that the image of Lu Xun that was used by LELECHA resembled a famous painting of Lu Xun by Yang Zhiguang (杨之光), potentially also infringing on Yang’s copyright.

But there are more reasons why people online are upset about the Lu Xun x LELECHA marketing campaign. One is how the use of the word “smoky” is seen as disrespectful towards Lu Xun. Lu Xun was known for his heavy smoking, which ultimately contributed to his early death.

It’s also ironic that Lu Xun, widely seen as a Marxist, is being used as a ‘brand ambassador’ for a commercial tea brand. This exploits Lu Xun’s image for profit, turning his legacy into a commodity with the ‘smoky oolong’ tea and related merchandise.

“Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you in an article. ”

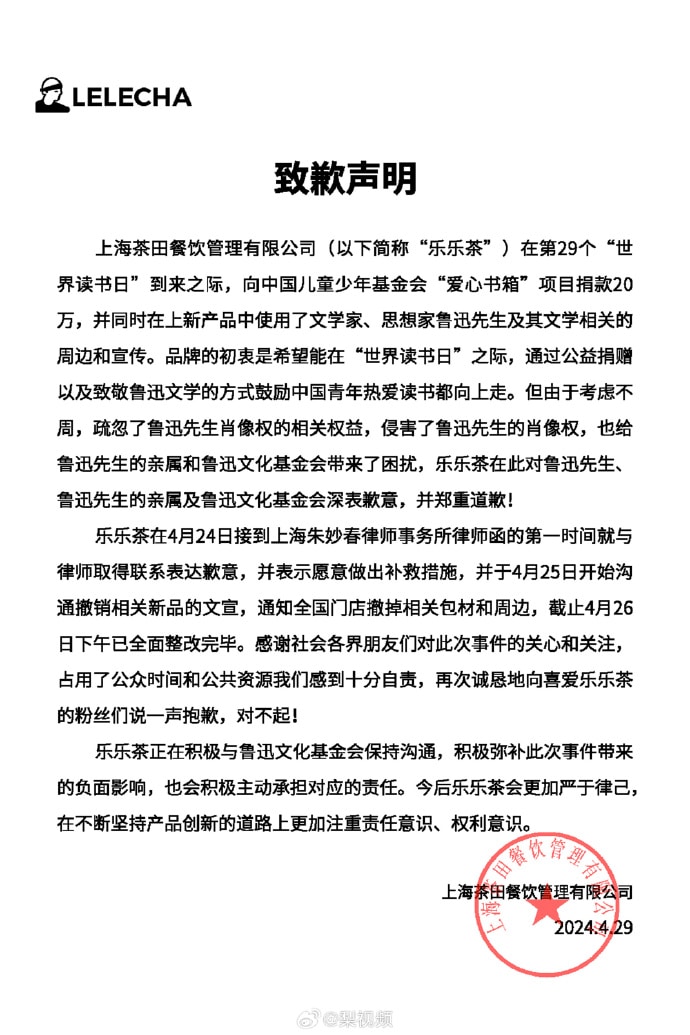

On April 29, LELECHA finally issued an apology to Lu Xun’s relatives and the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation for neglecting the legal aspects of their marketing campaign. They claimed it was meant to promote reading among China’s youth. All Lu Xun materials have now been removed from LELECHA’s stores.

Statement by LELECHA.

On Chinese social media, where the hot tea became a hot potato, opinions on the issue are divided. While many netizens think it is unacceptable to infringe on Lu Xun’s portrait rights like that, there are others who appreciate the merchandise.

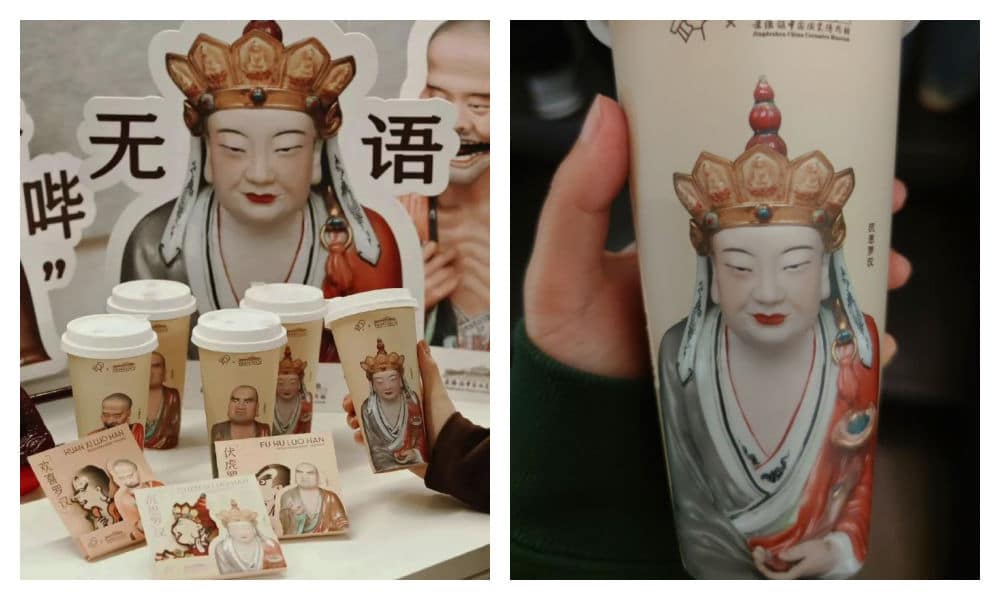

The LELECHA controversy is similar to another issue that went trending in late 2023, when the well-known Chinese tea chain HeyTea (喜茶) collaborated with the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum to release a special ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ (佛喜) latte tea series adorned with Buddha images on the cups, along with other merchandise such as stickers and magnets. The series featured three customized “Buddha’s Happiness” cups modeled on the “Speechless Bodhisattva” (无语菩萨), which soon became popular among netizens.

The HeyTea Buddha latte series, including merchandise, was pulled from shelves just three days after its launch.

However, the ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ success came to an abrupt halt when the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Shenzhen intervened, citing regulations that prohibit commercial promotion of religion. HeyTea wasted no time challenging the objections made by the Bureau and promptly removed the tea series and all related merchandise from its stores, just three days after its initial launch.

Following the Happy Buddha and Lu Xun milk tea controversies, Chinese tea brands are bound to be more careful in the future when it comes to their collaborative marketing campaigns and whether or not they’re crossing any boundaries.

Some people couldn’t care less if they don’t launch another campaign at all. One Weibo user wrote: “Every day there’s a new collaboration here, another one there, but I’d just prefer a simple cup of tea.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Schoppa, Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia UP, 159.

[2]Zhong, Xueping. 2010. “Who Is Afraid Of Lu Xun? The Politics Of ‘Debates About Lu Xun’ (鲁迅论争lu Xun Lun Zheng) And The Question Of His Legacy In Post-Revolution China.” In Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China, 257–284, 262.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?