China Media

No More Online Anti-Islam Terms Allowed on Weibo – but Discussions Continue Anyway

After various controversies, Chinese authorities have now blocked various Islam-related words by Chinese netizens on Weibo.

Published

7 years agoon

Chinese authorities have recently blocked various Islam-related words invented by Chinese netizens. The ban comes after consecutive online controversies on the topic of Chinese Muslims and Islam in China; the tone of the discussions reportedly “undermines ethnic unity.”

Posts containing terms such as “green religion” and “peaceful religion,” or any other online terms relating to Islam or Muslims invented by Chinese netizens, are currently banned from Chinese social media.

Chinese state media outlet Global Times reports that the ban comes amid an online backlash against national policies which some deem “overly favorable to Muslim minorities.”

Anti-Islamic Sentiments on Weibo

Anti-Islamic sentiments have been on the rise on Weibo over recent years, and often peak when people disagree with alleged “affirmative discrimination policies” toward Chinese Muslim minorities. China has an estimated 23 million Muslims.

One such incident occurred in 2016, when a Chinese university introduced separate shower cabins for Muslim students that offered complete privacy, while the ordinary dorm showers are usually open.

The case triggered anger online, especially among students, of whom some wrote: “I also have the f**cking rule that nobody should see me shower, am I going to have an exclusive shower cabin now?”

In July, online reports about the introduction of ‘Halal Only’ food delivery boxes also evoked anger as it sparked discussions about the ‘halalifaction‘ of food in China.

Image of food delivery box that says “special use for halal food.”

A very recent incident involved a case where a girl was harassed by a Muslim man on the Bund in Shanghai. When her online report was taken offline, and police did not give out any background details about the suspect, Weibo users complained that religious sensitivities were placed above personal safety.

Another incident took place in Tangshan in early September, where an alleged altercation took place between Muslim minorities and local staff at a toll station. Online rumors about the incident triggered a wave of anti-Islam comments, and videos of the incident were soon after deleted from Chinese social media.

“The Green Religion”

On Chinese social media, Islam is often referred to as the “peaceful religion” (和平教) or the “green religion” (绿教). While the first is mostly meant sarcastically, the second comes from the importance of the color green in Islam and is meant to refer to the religion in a negative way.

In the same type of derisive, derogatory online speak, Muslims are often referred to as “the greens” (绿绿) on Weibo. ‘Greenification’ (绿化) is another online word, meaning ‘Islamization.’

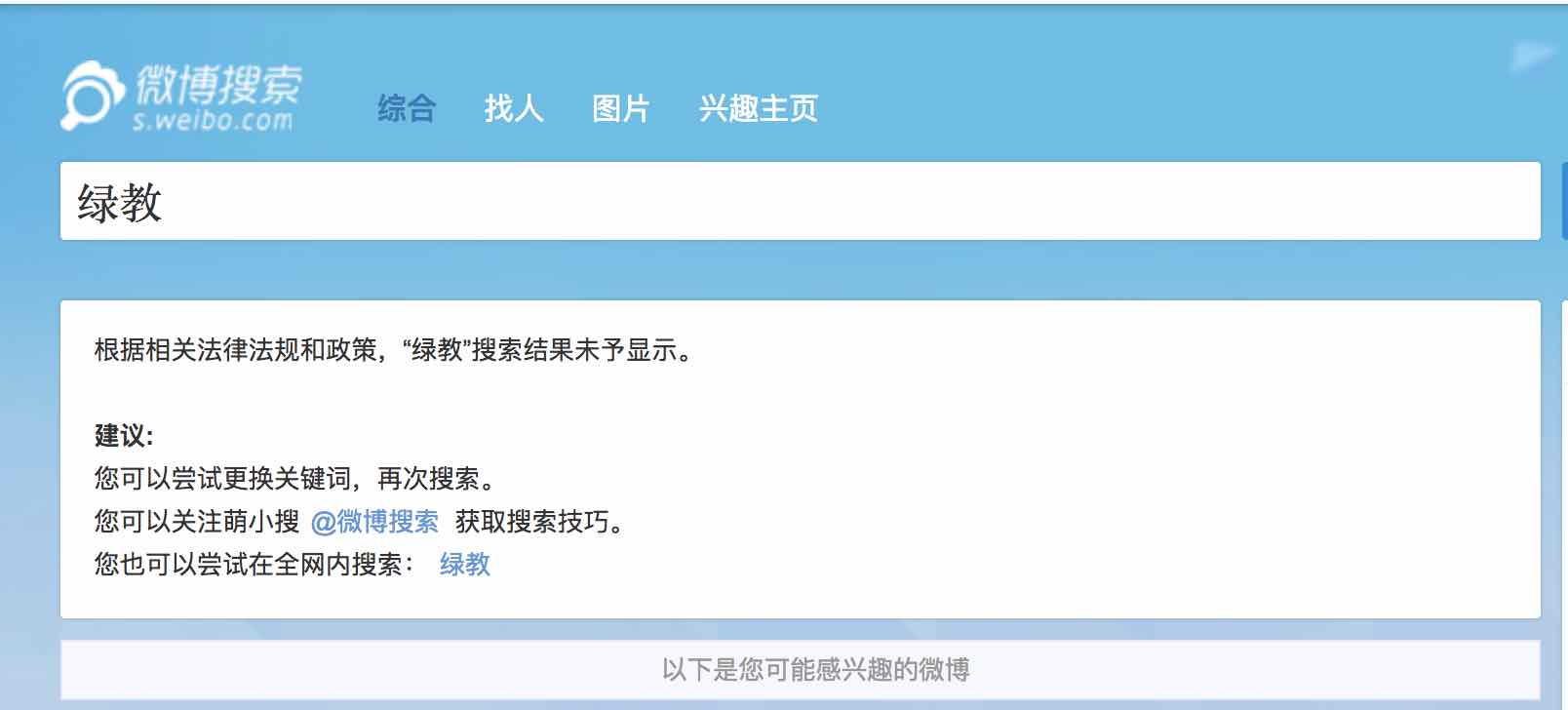

At the time of writing, abovementioned online terms such as “green religion” or “peaceful religion” were all banned from Weibo’s search function and showed no results.

No search results for ‘green religion’ on Weibo.

In its recent article, Global Times quoted a Beijing professor in saying that “it is necessary to timely remove radical phrases that discriminate against Islam and are biased against Muslims to prevent worsening online hatred towards the group” and that these online terms “severely undermine religious harmony and ethnic unity.”

In a Global Times column earlier this week, editor Shan Renpin conveyed a similar message in saying that there “might be negative consequences” to the government’s “protection of the harmony with minority groups and religions,” but that “overall, if the authorities would not do it this way, the other negative consequences are likely to be more serious.” (“这样做确实有时会有负面效果,但是综合起来看,如果官方不这样做,另外的负面效果很可能更大.”)

Ongoing discussions: Halal Mooncake

Despite the recent ban on certain terms, Chinese netizens still find ways to discuss Islam-related controversies. On Friday, another topic triggered heated discussions regarding halal mooncakes.

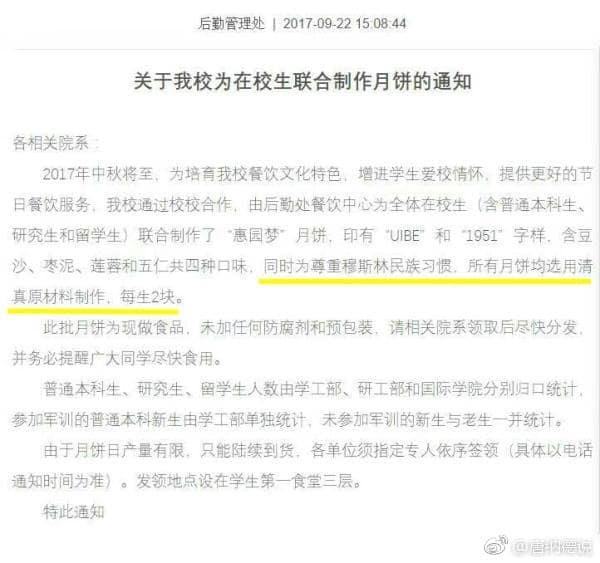

With the Chinese national Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋节) holiday nearing, many people discussed how a Chinese university stated that all of their mooncakes (the traditional snack for this festival) will be halal in consideration for their Muslim students.

Beijing’s University Of International Business And Economics (对外贸易经济大学) issued a notice on September 22 (see below) regarding the mooncakes, saying “to respect the traditions of our Muslim students, all our mooncakes will be made from halal ingredients.”

The issue attracted hundreds of comments, with many saying: “Don’t these schools know that Muslims don’t even celebrate Mid-Autumn Festival?”

“Respect the Muslims – for this minority, we all have to eat halal.”

“Since when did the Chinese Mid-Autumn Festival become a Muslim festival?”

Although much of the anger in this discussion is directed more so at the school’s organization (“Why does 99% of the people have to adapt for the 1%?”) than at its Muslim students, it does also include much hate speech towards Muslims in general.

One thing the latest controversy shows is that despite the fact that these discussions are now more heavily censored, their tone and terms are the same as before.

Although Global Times asserts that China’s “favorable policies” are intended to maintain ‘social harmony’ and accelerate ‘greater ethnic unity,’ most netizens commenting on these issues do not seem to be on the same page. Typical comments said: “How can they say we’re harming national unity by talking about Muslims?” and “I just don’t understand [..]. When did religion become a minority? Can a religion represent minorities?”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Media

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Chinese commenters discuss how the bullet aimed at Trump has turned into a moment of triumph.

Published

2 weeks agoon

July 14, 2024

The assassination attempt on former US President Trump at a Pennsylvania campaign event has become a major topic on Chinese social media, where Trump’s swift reaction and defiant gesture after the shooting have not only sparked discussions but also fueled the “Comrade Trump” meme machine.

The chaos that erupted when former US President Trump was injured—a bullet grazing his ear—in an assassination attempt at a Pennsylvania campaign event has become a top trending topic on Chinese social media today.

Trump sustained minor injuries, and the moment he raised his arm to cheer shortly before being evacuated from the stage has already become iconic, captured in widely circulated photographs.

Shortly after the shooting, a shooter armed with a rifle was killed by a US Secret Service counter sniper. The FBI identified the shooter as Thomas Matthew Crooks, a 20-year-old local.

The incident, which occurred on the afternoon of July 13th US local time, resulted in one audience member killed and two others critically injured.

“The campaign efforts will be as smooth as a flying bullet”

On Chinese social media platform Weibo, there are multiple trending hashtags related to the incident, such as “Trump Was Shot” (#特朗普遭遇枪击#, 370 million views); “Trump Says Bullet Pierced His Right Ear” (#特朗普称右耳被子弹击穿#, 440 million views); “Reporter Captures Bullet Grazing Trump’s Ear” (#记者拍到子弹划过特朗普耳朵画面#, 60 million); “Identity of Trump Shooter Confirmed” #枪击特朗普枪手身份确认#, 80 million views). By Sunday afternoon, China local time, half of the top ten hot search topics on Weibo were related to the Trump rally shooting.

“Today, the entire world is watching Trump,” one Chinese Weibo blogger wrote (@乐卡数码).

Political and social commentator Hu Xijin (@胡锡进) reposted a tweet from X by American media influencer Jackson Hinkle, comparing a photo of Trump raising a clenched fist after the shooting to Biden on the ground after falling off his bike near his Delaware home two years ago.

Hu Xijin wrote: “The bullet’s trajectory is so clear, just like how the campaign efforts will now be as fast [smooth] as the flying bullet,” (“好清晰的弹道,和与子弹飞得一样快的助选”).

Post by Hu Xijin

Before this, Hu also commented: “Trump was shot in the ear. This news has shocked everyone. My first reaction after waking up to this news was, ‘how could this happen?’ and I instinctively believe that this incident will garner Trump a lot of sympathy, bringing him one step closer to returning to the White House.”

Media commentator “Media Backpacker” (@媒体背包客) commented on Trump’s quick reaction, noting how he swiftly ducked under the podium after the first shots were fired.

“Several Secret Service agents rushed forward, using their bodies as shields,” he wrote. “Just this scene alone seemed much more professional compared to the attack on Shinzo Abe.” Former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe was shot and killed during a campaign event in the city of Nara, Japan, in 2022.

‘Media Backpacker’ also commented: “The person most harmed by Trump getting injured is not Trump himself, but his opponent, Biden.” Many other Weibo commenters also suggested that this dramatic event is rapidly shifting American voter support toward Trump.

“Just based on his quick reaction and how quickly he crouched, I’d vote Trump. If it were Biden, he probably wouldn’t have been able to crouch at all,” one top commenter on Weibo said.

Another commenter dismissed any rumors of the incident being staged: “It’s impossible to stage this; don’t mythologize the sniper. It’s not that precise. A bullet grazing the ear is extremely, extremely, extremely dangerous. No one would risk their life like that.”

Overall, commenters on Chinese social media suggested that the incident will boost Trump’s popularity and solidify his position in the presidential campaign.

On Sunday afternoon, China local time, official channels reported that Xi Jinping has expressed his sympathies to Trump following the shooting incident in Pennsylvania. China’s Foreign Ministry has also addressed the attempted assassination, expressing concern (#习主席已向特朗普表达慰问#).

“From a journalistic perspective, this is the perfect photo”

Besides online discussions on Trump’s quick reaction and the political implications, there’s a lot of interest in the iconic photo of Trump raising his fist, captured by Evan Vucci, who previously won the Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography for his coverage of George Floyd protests.

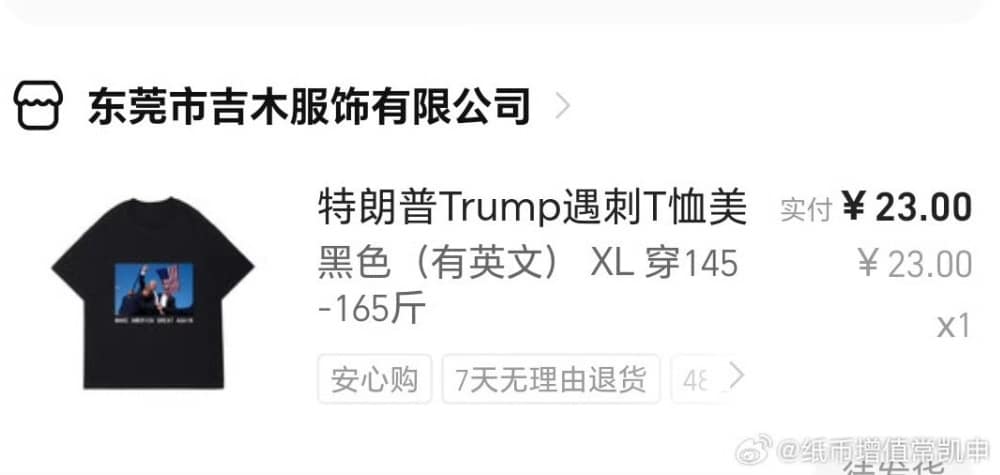

Some netizens noticed that sellers on several Chinese e-commerce platforms soon started selling T-shirts featuring the now famous photo of the incident, priced between 20-49 yuan ($3-$7). Some stores displayed that they had already sold over 10 items, but this merchandise was soon taken offline in various places.

“From a journalistic perspective, this is the perfect photo,” the well-known knowledge blogger Pingyuan Gongzi Zhao Sheng (@平原公子赵胜) wrote: “The destined son of America facing life-threatening danger, his face smeared with blood, with a clenched fist, roaring: “‘Fight! Fight!’ There’s no need to compare anymore; Biden is suffering a crushing defeat, and the Democrats are bewildered. This scene matches the most traditional American image in Hollywood movies. People don’t care who he is or who he serves, but the president must be tough, hard to defeat, a fearless “barbarian,” a “man of steel.”

“Did Trump write the script for Biden’s press conference?”

As this incident is being framed as a triumph for Trump, it further strengthens his position, especially following Biden’s recent damaging performances.

Earlier this week, Biden mistakenly referred to Ukrainian President Zelensky as “President Putin” during the NATO summit, sparking various hashtags on Chinese social media and making Biden a laughing stock for many netizens.

This was not the only mistake Biden made. On Thursday, he mistakenly referred to Vice President Kamala Harris as “Vice President Trump” during his solo press conference in Washington. In that same conference, Biden also talked about “getting Japan and South Korea back together again.”

Another post by American media influencer Jackson Hinkle being shared on Chinese social media platform Weibo.

Following a messy debate performance against Trump on June 27, voices suggesting it may be time for Biden to step down are growing louder. All of this sparked more discussions on Weibo, where many find the situation funny, suggesting: “Did Trump write the script for this [press conference]?”

Now that the bullet aimed at Trump has turned into a moment of triumph, the contrast between the two US presidential candidates has only grown more stark.

“The bullet pierced my ear, but I can still hear the voice of the Party”

On Chinese social media, Trump is often referred to as “Comrade Jianguo” (建国同志 [Comrade Build-Country]), a nickname that has been circulating for years.

Trump is nicknamed “Comrade Trump” or “Build the Country Trump” (Chuān Jiànguó, 川建国) for “making China great again.” These are just some among many existing memes and jokes about the former US president on the Chinese internet. One reason to call him “Comrade Jianguo” or “Build the Country Trump” is to make fun of his words and actions, suggesting that his leadership only brings America down and in doing so, also further accelerates the rise of China.

But through the years, these playful nicknames have started to reflects a blend of mockery and affection, highlighting the humorous perspective Chinese social media users have towards Trump and his political antics (read more).

In a similar tongue-in-cheek fashion, some Weibo users have now edited the iconic Trump photo, portraying him as a communist hero with the caption: “Workers of the world, unite!” (全世界无产者联合起来) (see featured image).

Other similar edits included captions like: “Long live the great and glorious Communist Party of China!” and “The bullet pierced my ear, but I can still hear the voice of the Party.”

Meme: “Long live the great and glorious Communist Party of China!”

Meme: “The bullet pierced my ear, but I can still hear the voice of the Party.”

Some joked that Trump’s right ear being pierced further emphasized his supposed loyalty to China, comparing him to the panda A Bao, who is missing part of his right ear after being bitten by another panda.

Another commenter wrote: “I wish Comrade Jianguo a speedy recovery, may he continue to work hard for the ultimate mission entrusted to him by the Party.”

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Media

The Beishan Park Stabbings: How the Story Unfolded and Was Censored on Weibo

A timeline of the censorship & reporting of the Jilin Beishan Park stabbing incident on Chinese social media.

Published

2 months agoon

June 12, 2024

The recent stabbing incident at Beishan Park in Jilin city, involving four American teachers, has made headlines worldwide. However, on the Chinese internet, the story was initially kept under wraps. This is a brief overview of how the incident was reported, censored, and discussed on Weibo.

On Monday, June 10, four Americans were stabbed while visiting Beishan park in Jilin.

Video footage of the victims lying on the ground in the park was viewed by millions of people outside the Chinese internet by Monday afternoon.

Despite the serious and unusual nature of such an attack on foreigners visiting China, it took about an entire day for the news to be reported by official Chinese channels.

How the Beishan Incident Unfolded Online

In the afternoon of June 10, news about four foreigners being stabbed in Jilin’s Beishan Park started circulating online.

Among the first online accounts to report this incident was the well-known Chinese-language X account ‘Li Laoshi’ (李老师不是你老师, @whyyoutouzhele), which has 1.5 million followers, along with the news account Visegrád 24 (@visegrad24), which has 1 million followers on X.

They both posted a video showing the incident’s aftermath, which soon went viral on X and beyond. It showed how three victims – one female and two male – were lying on the ground at the park, bleeding heavily while waiting for medical help. A police officer was already at the scene.

As soon as the video and tweets triggered discussions in the English-language social media sphere, it was clear that Chinese social media platforms were censoring and blocking mentions of the incident.

By Monday night, China local time, many Weibo commenters had started writing about what had happened in Beishan Park earlier that day, but their posts became unavailable.

Some bloggers wrote about receiving an automated message from Weibo management that their posts had been taken offline. Others started posting about “that thing in Jilin,” but even those messages disappeared. On other platforms, such as Douyin, the story was also being contained.

By 21:00-22:00 local time, a hashtag on Weibo, “Jilin Beishan Park Foreigners” (吉林北山外国人), briefly became the second most-searched topic before it was taken offline. Weibo stated: “According to relevant laws, regulations, and policies, the content of this topic is not shown.”

A hashtag about the Beishan stabbings soon became one of the hottest search queries before it disappeared.

While netizens came up with more creative words and other descriptions to talk about what had happened, the focus shifted from what had happened in Beishan Park to why the topic was being censored. “What’s this? Why can’t we talk about it?” one Weibo user wondered: “Not a single piece of news!”

Around 23:30 local time, another blogger posted: “It seems to be real that four foreigners were stabbed in Jilin’s Beishan Park this afternoon. We’ll have to see when it will formally be reported on Weibo.” Others questioned, “Why is the Jilin incident so tightly covered up on the internet?”

Around 04:00 local time on June 11, the first media outlet to really report on what had happened was Iowa Public Radio (IPR News). Before that time, one Iowan citizen had already commented on X that their sister-in-law was one of the victims involved.

One victim’s family had told IPR News that the individuals involved were four Cornell College instructors. All four survived and were recovering at a nearby hospital after being stabbed during a park visit in China.

The instructors were part of a partnership with Beihua University in Jilin. Cornell College and Beihua University have had an active partnership since 2018, with Beihua funding Cornell instructors to visit China, travel, and teach during a two-week period. Members from both institutions were visiting the public park in Jilin City when they were attacked. The visit was likely intended as a sightseeing and relaxation opportunity during the Dragon Boat Festival holiday, when many people visit the park.

As reported by IPR News reporter Zachary Oren Smith (@ZacharyOS), U.S. Representative Mariannette Miller-Meeks stated that her office was working with the U.S. Embassy to ensure the victims would receive care for their injuries and safely leave China.

Hu Xijin Post

Now that news of the attack on four Americans was all over X, soon picked up by dozens of international news outlets, the Chinese censorship of the story seemed unusual, considering the magnitude of the story.

Furthermore, there had still been no official statement from the Chinese side, nor any news reports on the suspect and whether or not he had been detained.

By the morning of June 11, an internal, unverified BOLO notice from the Jilin city Chuanying police office circulated online. It identified the suspect as 55-year-old Jilin resident Cui Dapeng (崔大鹏), who was still at large. The notice also clarified that there were not four but five victims in total.

At 11:33 local time, it seemed that the wall of censorship surrounding the incident was suddenly lifted when Chinese political and social commentator Hu Xijin (胡锡进), who has nearly 25 million followers on Weibo, posted about what had happened.

He based his post on “Western media reports,” and commented that this is a time when Chinese and American sides are actually promoting exchange. He saw the incident as a “random” one, which, regardless of the attacker’s motive, does not reflect broader sentiment within Chinese society. He concluded, “I also hope and believe that this incident will not negatively affect the exchanges between China and the US.”

Hu’s post spurred a flurry of discussions about the Beishan Park incident, turning it into a top-searched topic once again. His comments sparked controversy, with many disagreeing with his suggestion that the incident could potentially affect Sino-American exchanges. Many argued that there are numerous examples of Chinese people being attacked or even murdered in the US without anyone suggesting it would harm US-China relations.

Within approximately two hours of posting, Hu’s post was no longer visible and had disappeared from his timeline. This sudden deletion or blocking of his post again triggered confusion: Was Hu being censored? Why?

Later, screenshots of Hu Xijin’s post shared on social media were also censored.

A “Collision”

By the early Tuesday evening, June 11, Chinese official accounts and state media accounts finally issued a report on what had happened in what was now dubbed the “Beishan Park Stabbing Incident” (#吉林公安通报北山公园伤人案#).

Jilin authorities issued a report on what happened in Beishan Park.

A notice from local public security authorities stated that the first emergency call about a stabbing incident at the park came in at 11:49 in the morning on Monday, June 10, and police and medical assistance soon arrived at the scene.

The 55-year-old Chinese suspect, referred to as ‘Cui’ (崔某某), reportedly stabbed one of the Americans after they bumped into each other at the park (described as “a collision” 发生碰撞). The suspect then attacked the American, his three American companions, and a Chinese visitor who tried to intervene. Reports indicated that the victims were all transported to the hospital and were not in critical condition.

It was also stated that the suspect was arrested on the “same day,” without specifying the time and location of the arrest.

Later on Tuesday, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs addressed the incident during their regular press conference. Spokesperson Lin Jian (林剑) stated that local police had initially judged the case to be a random incident and that they were conducting further investigation (#外交部回应吉林北山公园伤人案#).

Boxer Rebellion References

With the discussions about the incident on Chinese social media less controlled, various views emerged, commenting on issues such as public safety in China, US-China relations, and anti-Western sentiments.

One notable trend during the early discussions of the incident is how many commenters referenced to the ‘Boxer Rebellion’ (1899–1901), an anti-foreign, anti-Christian uprising that took place during the final years of the Qing Dynasty and led to large-scale massacres of foreign residents. Many commenters believed the attacker had nationalist motives targeting foreigners.

Anti-american, nationalist sentiments also surfaced online. Some commenters laughed about the incident or praised the attacker for doing a “good job.”

However, the majority argued that this event should not be seen as indicative of a broader trend of foreign-targeted violence in China. They emphasized that Asians in America are far more frequently targeted in hate crimes than any Westerner in China, underscoring that this incident is just an isolated case.

This idea of the event being “random” (“偶然事件”) was reiterated in official reports, Hu Xijin’s column, and by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

But there are also those who think this might be a conspiracy, calling it bizarre for such a rare incident to occur just when Chinese tourism was finally starting to flourish in the post-Covid era: “Now that our tourism industry is booming, foreigners are getting stabbed? How could it be such a coincidence? Is it possible that this was arranged by spies from other countries?”

On Tuesday, social commentator Hu Xijin made a second attempt at posting about the Beishan Park incident. This time, his post was shorter and less outspoken:

“This appears to be a public security incident,” he wrote: “But this time, four foreign nationals were attacked. In every place around the world, there are criminal and public security incidents where foreigners become victims. China is one of the relatively safest countries in the world, but this incident still occurred in broad daylight in a tourist area. This reminds us, that we need to always keep enhancing the effectiveness of security measures to protect the safety of all Chinese and foreign nationals.”

Again, his post triggered some controversy as some bloggers discovered that Hu had previously argued against extra security checks at Chinese parks, which he deemed unnecessary. They felt he was now contradicting himself.

The differing views on Hu’s posts and the incident at large perhaps explain why the news was initially controlled and censored. Although censorship and control are inherent parts of the Chinese social media apparatus, the level of control over this story was quite unusual. Whether it was due to the suspect still being on the loose, public safety concerns, fears of rising nationalist sentiments, or the need to understand the full details before the story blew up, we will likely never know.

Nevertheless, this time, Hu’s post stayed up.

The Beishan Park incident is reportedly still under investigation.

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

Bruce Humes

September 24, 2017 at 3:43 pm

Good to see coverage here — in English — of issues and language relating to Islam currently under discussion on China’s Weibo in 2017.

Censorship extends beyond social media, of course. Muslim fiction writers in China dare not touch upon a whole host of issues, particularly recent laws and regulations that tightly restrict Muslim dress and worship in Xinjiang.

One result is an introspective sort of fiction writing in which Uyhgur authors turn the focus almost entirely on themselves, their families and the Uyghur community. A good example is Xinjiang’s Alat Asem (阿拉提·阿斯木). Han Chinese rarely figure in his Uyghur universe. Its hallmarks are serial womanizers, disparaging monikers, and a hybrid lingo with an appealing Central Asian flavor. His novel, Confessions of a Jade Lord (时间悄悄的嘴脸), will be published in English in 4Q 2017.

Another Uyghur writer to watch is Patigül ((帕蒂古丽), whose novel One-hundred Year Bloodline (百年血脉, due out in 4Q 2017 too), is the semi-autobiographical saga of a Xinjiang woman of mixed Uyghur, Hui and Han extraction who marries a Han husband and moves to Zhejiang. Obviously, there are Han characters, but the spotlight is clearly on Uyghur and Hui personalities, and their struggle to maintain their distinct ethnic identity.