China Society

Nobody’s Baby? Chinese Girl in Canceled Surrogacy Case Has No Birth Certificate, No Hukou

From surrogacy baby to ‘heihaizi’ – her biological parents canceled the surrogacy agreement, but she was born anyway.

Published

3 years agoon

The news story of a child born through surrogacy is the talk of the day on Weibo, leading to heated discussions on China’s ‘underground’ surrogacy practices.

The tragic story of a 3-year-old girl born through surrogacy is top trending on Chinese social media today, where the child is referred to as the ‘unregistered surrogacy girl’ (“黑户代孕女童”).

The child was meant to grow up with her two biological parents, but when the surrogate mother tested positive for a syphilis infection halfway through the pregnancy, the intended parents canceled the surrogacy agreement. The story was told in a short video report by Chinese news outlet The Paper.

The poverty-stricken surrogate mother ended up having the baby herself, but could not afford her bills and sold the baby’s birth certificate. The biological parents have refused to take responsibility for the girl.

Without her formal papers and household registration, the 3-year-old girl cannot go to school and is not registered anywhere.

From Surrogacy Baby to ‘Heihaizi’

On January 12, Chinese media outlet Time Weekly (时代周报) published a lengthy interview with the surrogacy mother recounting the entire story of the canceled surrogacy agreement.

The story starts in 2016 when the then 38-year-old* Wu Chuanchuan (吴川川, alias) became a surrogate mother as a way to earn money. The older couple who wanted a baby came from Inner Mongolia and had previously lost a child. *(In the interview, Wu claims she is actually younger than the age indicated on her official papers, which say she is now 47.)

The surrogacy agreement, arranged through an underground company, was settled at 170,000 yuan ($26,200). It concerned a gestational surrogacy, in which the child is not biologically related to the surrogate mother.

During the pregnancy, Wu was living together with other surrogate mothers. When she was four months pregnant, she unexpectedly tested positive for syphilis. Wu says she suspects that the infection was spread within the small surrogacy mother community she lived in.

Syphilis in pregnant women is risky and can have a major impact on the baby’s health. It can cause miscarriage, stillbirth, or death as a result of the infection as a newborn.

“The intended parents decided to withdraw from the surrogacy arrangement, asking for a refund and offering to pay for an abortion.”

Due to syphilis, the intended parents of the baby decided to withdraw from the surrogacy arrangement, asking for a refund and offering to pay for an abortion. Wu would only receive 20,000 yuan ($3085).

This situation left Wu, who already felt the fetus moving, in a very difficult situation. She eventually refused to terminate the pregnancy and withdrew from the surrogacy agency’s home.

Staying at cheap hotels in the city of Chengdu and unable to find a suitable adoption family, Wu eventually gave birth to a baby girl that she would raise herself.

But there was one major issue: money. Wu already could not afford the hospital admittance fee, let alone the 12,000 yuan ($1850) in hospital bills she had to pay after needing a C-section delivery.

To pay for her medical bills, Wu was forced to take desperate measures and ended up selling her baby’s birth certificate. Through the internet’s black market, she found someone who would pay 20,000 yuan ($3085) for it.

Once the baby was born, things looked up for Wu. She soon married a kind man who was willing to raise baby girl ‘Xiao Rang’ (小让, alias) together with her, and the child’s congenital syphilis was cured.

But Xiao Rang still had no birth certificate, and thus no hukou.

Wu and Xiao Rang, screenshot from The Paper video report.

The hukou or ‘household registration’ system is a registered permanent residence policy. A hukou is assigned at birth based on one’s community and family. China’s hukou system, amongst others, separates rural from urban citizens and is essential to access social services, including education and healthcare.

Without a hukou, the child cannot attend kindergarten, and will not be able to go to school – she will be a heihaizi (黑孩子, lit. ‘black child’), an ‘illegal child’ not registered anywhere.

In December of 2020, as reported by The Paper, Wu traveled from Chengdu to Inner Mongolia in search of her daughter’s biological parents.

The girl’s intended parents turned out to have twin sons now. They bought a house and went through the process to get their twins through another surrogate mother. After spending approximately 700,000 yuan ($108,000), the family allegedly could not afford to also be legally responsible for Xiao Rang. Afraid of the consequences, the 50-year-old biological father initially also seemed unwilling to formally arrange adoption papers for his daughter, Wu told Time Weekly.

Banned Baby Business

On Weibo, a hashtag page about Xiao Rang’s story received over 550 million views on Tuesday, making it one of the most-discussed topics on January 12 (#首个遭代孕客户退单女童无法上户#).

Due to the media attention, and the biological father’s identity being exposed, the case was still developing while Chinese netizens looked on.

According to the latest reports, Xiao Rang’s biological father will now provide assistance in arranging registration papers for the little girl while Wu Chuanchuan will still raise the child.

The fact that the father himself came forward to tell his side of the story also became a trending topic (#遭退单代孕女童生物学父亲现身#), garnering over 260 million views by Tuesday night Beijing time. The biological father confirms that they gave up on the baby once they were informed of Wu’s syphilis infection, and that they did not expect Wu to have the baby after all.

Meanwhile, on social media, there seems to have been a shift in sentiments regarding this story. Netizens initially sided with the surrogate mother and her tragic story.

But as the media continue to report on this story, more and more people are starting to doubt Wu’s sincerity, wondering if she used media exposure to portray herself as a victim to gain the public’s sympathy.

Online commenters criticize Wu for being part of the surrogacy agreement, for choosing to have the child despite her syphilis, and for selling the child’s birth certificate. Many call her ‘immoral’ and ‘irresponsible.’

“Surrogacy exploits women, and it is a serious violation of social ethics and morals. Taking part in surrogacy should be severely punished.”

Surrogacy has been a hot topic on Chinese social media recently. Just a month ago, a short film titled “10 Months With You” (‘宝贝儿’) by famous Chinese director Chen Kaige (陈凯歌) also stirred controversy for supposedly presenting surrogacy in China in a relatively positive light.

Screenshot from “10 Months With You” by Chen Kaige

The 30-minute film revolves around a young girl who signs a surrogacy contract with intended parents without telling her boyfriend. When she gets emotionally attached to the baby during her pregnancy, things get complicated. But she eventually is persuaded by her boyfriend that the child is not intended to be with them, after which she is willing to part with the baby.

Chinese state media outlets, including Global Times and China Daily emphasized that surrogacy is illegal in China and that those who take part in surrogacy will face fines or even criminal prosecution.

Nevertheless, the practice of surrogacy is a somewhat legislative grey area in China. China’s Ministry of Health introduced regulations in 2001 that made it illegal for medical staff to offer surrogacy services. In 2015, there were official plans to completely curb surrogate pregnancies. But that strict ban on surrogacy pregnancies was later reversed.

In 2017, People’s Daily even published a controversial article that suggested a loosening of surrogacy bans to boost China’s birth rates. Meanwhile, there have been ongoing reports about China’s booming underground surrogacy market (here, here ).

In 2018, state media outlet Global Times quoted Qiu Renzong, a bioethics expert at the Chinese Academy of Social Science in saying: “The Chinese government should consider setting some rules to allow surrogacy in certain circumstances.”

With discussions on Xiao Rang’s case and surrogacy in China being a major topic on Weibo, the legal side is also receiving much attention. Law expert Zhang San (@普法达人张三) uses the hashtag “Criminalize Surrogacy” (#建议代孕入刑#) when he writes:

“Although surrogacy is illegal, it is a blank space in the criminal law. Surrogacy exploits women, and it is a serious violation of social ethics and morals. Taking part in surrogacy should be severely punished. If the freedom is not restricted, it will surely lead to exploitation of the weak by the strong.”

Some people on Weibo argue that most of the people involved in Xiao Rang’s story are filthy and immoral, and that they need to be punished. But virtually everyone agrees that the little girl needs to be registered in order to still have a chance to lead a normal life: “The child is innocent.”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2021 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy.

Published

5 days agoon

May 3, 2024

It seemed like such a good idea. For this year’s World Book Day, Chinese tea brand LELECHA (乐乐茶) put a spotlight on Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881-1936), one of the most celebrated Chinese authors the 20th century and turned him into the the ‘brand ambassador’ of their special new “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙) milk tea.

LELECHA is a Chinese chain specializing in new-style tea beverages, including bubble tea and fruit tea. It debuted in Shanghai in 2016, and since then, it has expanded rapidly, opening dozens of new stores not only in Shanghai but also in other major cities across China.

Starting on April 23, not only did the LELECHA ‘Smoky Oolong” paper cups feature Lu Xun’s portrait, but also other promotional materials by LELECHA, such as menus and paper bags, accompanied by the slogan: “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” (“老烟腔,新青年”). The marketing campaign was a joint collaboration between LELECHA and publishing house Yilin Press.

Lu Xun featured on LELECHA products, image via Netease.

The slogan “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” is a play on the Chinese magazine ‘New Youth’ or ‘La Jeunesse’ (新青年), the influential literary magazine in which Lu’s famous short story, “Diary of a Madman,” was published in 1918.

The design of the tea featuring Lu Xun’s image, its colors, and painting style also pay homage to the era in which Lu Xun rose to prominence.

Lu Xun (pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a leading figure within China’s May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1915-24) is also referred to as the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance. It was the cultural revolution brought about by the political demonstrations on the fourth of May 1919 when citizens and students in Beijing paraded the streets to protest decisions made at the post-World War I Versailles Conference and called for the destruction of traditional culture[1].

In this historical context, Lu Xun emerged as a significant cultural figure, renowned for his critical and enlightened perspectives on Chinese society.

To this day, Lu Xun remains a highly respected figure. In the post-Mao era, some critics felt that Lu Xun was actually revered a bit too much, and called for efforts to ‘demystify’ him. In 1979, for example, writer Mao Dun called for a halt to the movement to turn Lu Xun into “a god-like figure”[2].

Perhaps LELECHA’s marketing team figured they could not go wrong by creating a milk tea product around China’s beloved Lu Xun. But for various reasons, the marketing campaign backfired, landing LELECHA in hot water. The topic went trending on Chinese social media, where many criticized the tea company.

Commodification of ‘Marxist’ Lu Xun

The first issue with LELECHA’s Lu Xun campaign is a legal one. It seems the tea chain used Lu Xun’s portrait without permission. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s great-grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation, quickly demanded an end to the unauthorized use of Lu Xun’s image on tea cups and other merchandise. He even hired a law firm to take legal action against the campaign.

Others noted that the image of Lu Xun that was used by LELECHA resembled a famous painting of Lu Xun by Yang Zhiguang (杨之光), potentially also infringing on Yang’s copyright.

But there are more reasons why people online are upset about the Lu Xun x LELECHA marketing campaign. One is how the use of the word “smoky” is seen as disrespectful towards Lu Xun. Lu Xun was known for his heavy smoking, which ultimately contributed to his early death.

It’s also ironic that Lu Xun, widely seen as a Marxist, is being used as a ‘brand ambassador’ for a commercial tea brand. This exploits Lu Xun’s image for profit, turning his legacy into a commodity with the ‘smoky oolong’ tea and related merchandise.

“Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you in an article. ”

On April 29, LELECHA finally issued an apology to Lu Xun’s relatives and the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation for neglecting the legal aspects of their marketing campaign. They claimed it was meant to promote reading among China’s youth. All Lu Xun materials have now been removed from LELECHA’s stores.

Statement by LELECHA.

On Chinese social media, where the hot tea became a hot potato, opinions on the issue are divided. While many netizens think it is unacceptable to infringe on Lu Xun’s portrait rights like that, there are others who appreciate the merchandise.

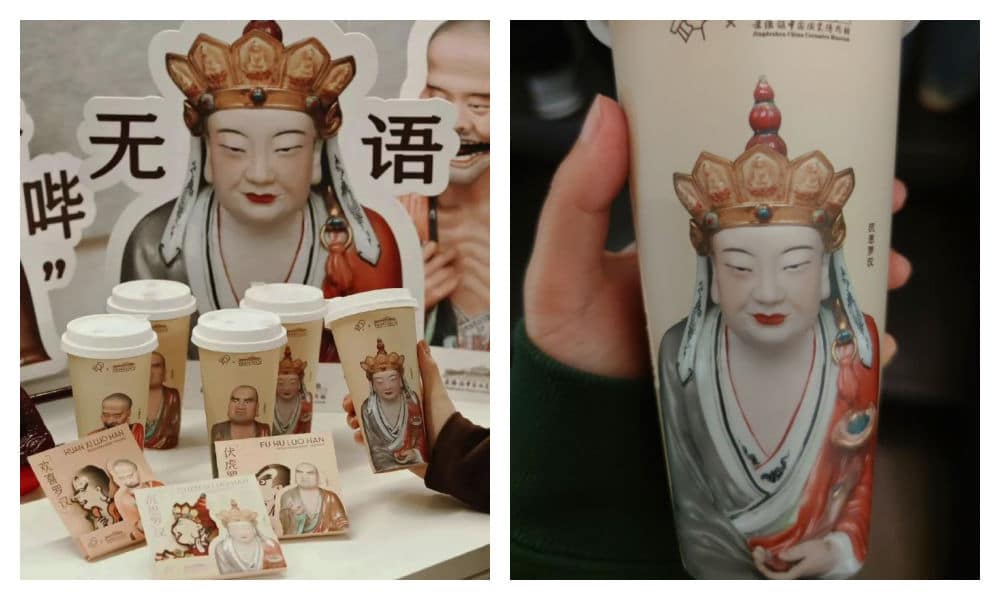

The LELECHA controversy is similar to another issue that went trending in late 2023, when the well-known Chinese tea chain HeyTea (喜茶) collaborated with the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum to release a special ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ (佛喜) latte tea series adorned with Buddha images on the cups, along with other merchandise such as stickers and magnets. The series featured three customized “Buddha’s Happiness” cups modeled on the “Speechless Bodhisattva” (无语菩萨), which soon became popular among netizens.

The HeyTea Buddha latte series, including merchandise, was pulled from shelves just three days after its launch.

However, the ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ success came to an abrupt halt when the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Shenzhen intervened, citing regulations that prohibit commercial promotion of religion. HeyTea wasted no time challenging the objections made by the Bureau and promptly removed the tea series and all related merchandise from its stores, just three days after its initial launch.

Following the Happy Buddha and Lu Xun milk tea controversies, Chinese tea brands are bound to be more careful in the future when it comes to their collaborative marketing campaigns and whether or not they’re crossing any boundaries.

Some people couldn’t care less if they don’t launch another campaign at all. One Weibo user wrote: “Every day there’s a new collaboration here, another one there, but I’d just prefer a simple cup of tea.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Schoppa, Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia UP, 159.

[2]Zhong, Xueping. 2010. “Who Is Afraid Of Lu Xun? The Politics Of ‘Debates About Lu Xun’ (鲁迅论争lu Xun Lun Zheng) And The Question Of His Legacy In Post-Revolution China.” In Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China, 257–284, 262.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Online reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among Chinese netizens.

Published

3 weeks agoon

April 18, 2024

The recent marriage announcement of the renowned Chinese calligrapher/painter Fan Zeng and Xu Meng, a Beijing TV presenter 50 years his junior, has sparked online discussions about the life and work of the esteemed Chinese artist. Some netizens think Fan lacks the integrity expected of a Chinese scholar-artist.

Recently, the marriage of a 86-year-old Chinese painter to his bride, who is half a century younger, has stirred conversations on Chinese social media.

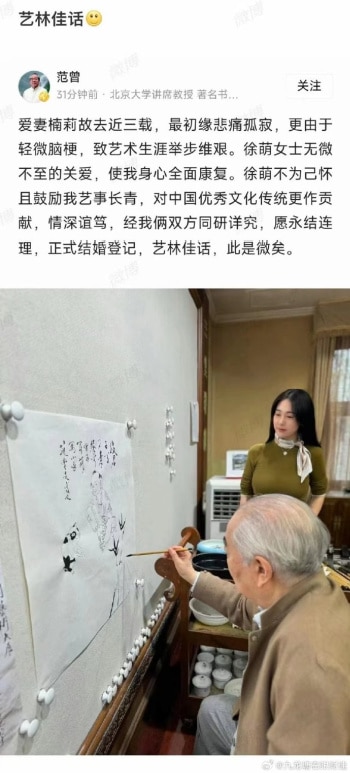

The story revolves around renowned Chinese artist, calligrapher, and scholar Fan Zeng (范曾, 1938) and his new spouse, Xu Meng (徐萌, 1988). On April 10, Fan announced their marriage through an online post accompanied by a picture.

In the picture, Fan is seen working on his announcement in calligraphic form.

Fan Zeng announces his marriage on Chinese social media.

In his writing, Zeng shares that the passing of his late wife, three years ago, left him heartbroken, and a minor stroke also hindered his work. He expresses gratitude for Xu Meng’s care, which he says led to his physical and mental recovery. Zeng concludes by expressing hope for “everlasting harmony” in their marriage.

Fan Zeng is a calligrapher and poet, but he is primarily recognized as a contemporary master of traditional Chinese painting. Growing up in a well-known literary family, his journey in art began at a young age. Fan studied under renowned mentors at the Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, including Wu Zuoren, Li Keran, Jiang Zhaohe, and Li Kuchan.

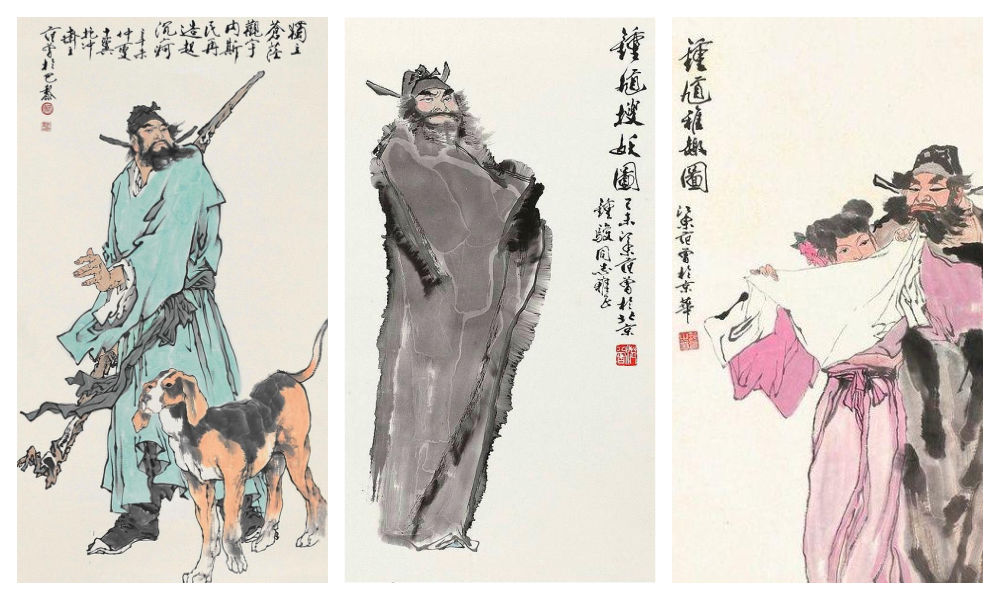

Fan gained global acclaim for his simple yet vibrant painting style. He resided in France, showcased his work in numerous exhibitions worldwide, and his pieces were auctioned at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in the 1980s.[1] One of Fan’s works, depicting spirit guardian Zhong Kui (钟馗), was sold for over 6 million yuan (828,000 USD).

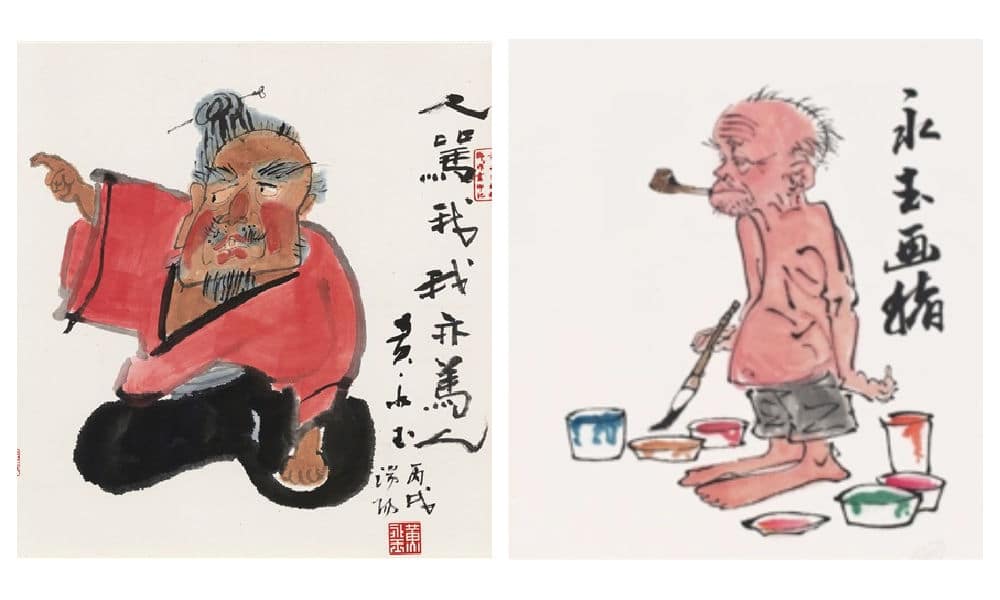

Zhong Kui in works by Fan Zeng.

In his later years, Fan Zeng transitioned to academia, serving as a lecturer at Nankai University in Tianjin. At the age of 63, he assumed the role of head of the Nankai University Museum of Antiquities, as well as holding various other positions from doctoral supervisor to honorary dean.

By now, Fan’s work has already become part of China’s twentieth-century art history. Renowned contemporary scholar Qian Zhongshu once remarked that Fan “excelled all in artistic quality, painting people beyond mere physicality.”

A questionable “role model”

Fan’s third wife passed away in 2021. Later, he got to know Xu Meng, a presenter at China Traffic Broadcasting. Allegedly, shortly after they met, he gifted her a Ferrari, sparking the beginning of their relationship.

A photo of Xu and her Hermes Birkin 25 bag has also been making the rounds on social media, fueling rumors that she is only in it for the money (the bag costs more than 180,000 yuan / nearly 25,000 USD).

On Weibo, reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among netizens. Despite Fan’s reputation as a prominent philanthropist, many perceive his recent marriage as yet another instance of his lack of integrity and shamelessness.

Fan Zeng and Xu Meng. Image via Weibo.

One popular blogger (@好时代见证记录者) sarcastically wrote:

“Warm congratulations to the 86-year-old renowned contemporary erudite scholar and famous calligrapher Fan Zeng, born in 1938, on his marriage to Ms Xu Meng, a 50 years younger 175cm tall woman who is claimed to be China’s number one golden ratio beauty. Mr Fan Zeng really is a role model for us middle-aged greasy men, as it makes us feel much less uncomfortable when we’re pursuing post-90s youngsters as girlfriends and gives us an extra shield! Because if contemporary Confucian scholars [like yourself] are doing this, then we, as the inheritors of Confucian culture, can surely do the same!“

Various people criticize the fact that Xu Meng is essentially just an aide to Fan, as she can often be seen helping him during his work. One commenter wrote: “Couldn’t he have just hired an assistant? There’s no need to turn them into a bed partner.”

Others think it’s strange for a supposedly scholarly man to be so superficial: “He just wants her for her body. And she just wants him for his inheritance.”

“It’s so inappropriate,” others wrote, labeling Fan as “an old bull grazing on young grass” (lǎoniú chī nèncǎo 老牛吃嫩草).

Fan is not the only well-known Chinese scholar to ‘graze on young grass.’ The famous Chinese theoretical physicist Yang Zhenning (杨振宁, 1922), now 101 years old, also shares a 48-year age gap with his wife Weng Fen (翁帆). Fan, who is a friend of Yang’s, previously praised the love between Yang and Weng, suggesting that she kept him youthful.

Older photo posted on social media, showing Fan attending the wedding ceremony of Yang Zhenning and his 48-year-younger partner Weng Fen.

Some speculate that Fan took inspiration from Yang in marrying a significantly younger woman. Others view him as hypocritical, given his expressions of heartbreak over his previous wife’s passing, and how there’s only one true love in his lifetime, only to remarry a few years later.

Many commenters argue that Fan Zeng’s conduct doesn’t align with that of a “true Confucian scholar,” suggesting that he’s undeserving of the praise he receives.

“Mr. Wang from next door”

In online discussions surrounding Fan Zeng’s recent marriage, more reasons emerge as to why people dislike him.

Many netizens perceive him as more of a money-driven businessman rather than an idealistic artist. They label him as arrogant, critique his work, and question why his pieces sell for so much money. Some even allege that the only reason he created a calligraphy painting of his marriage announcement is to profit from it.

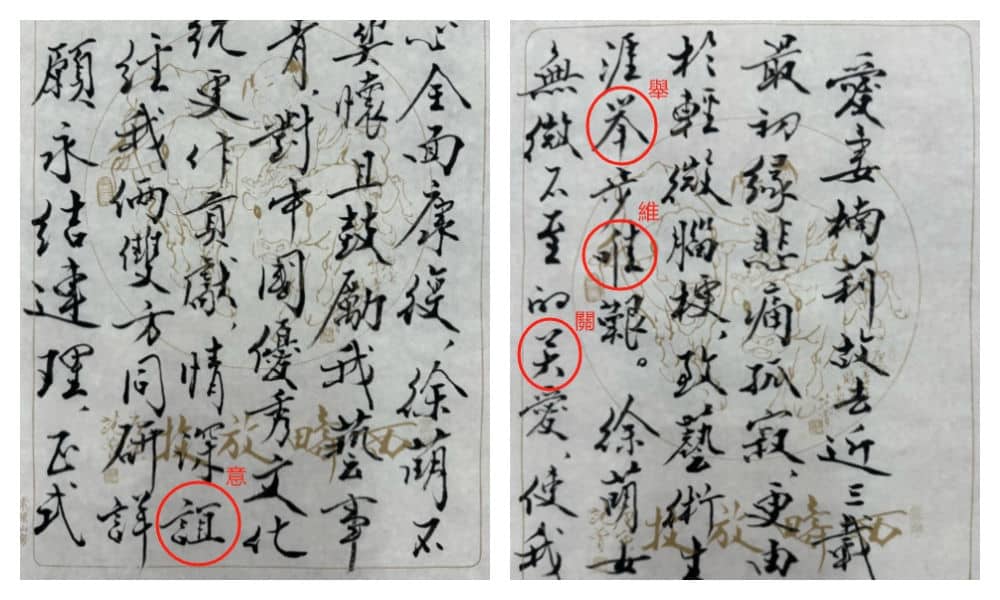

Others cast doubt on his status as a Chinese calligraphy ‘grandmaster,’ noting that his calligraphy style is not particularly impressive and may contain typos or errors. His wedding announcement calligraphy appears to blend traditional and simplified characters.

Netizens have pointed out what looks like errors or typos in Fan’s calligraphy.

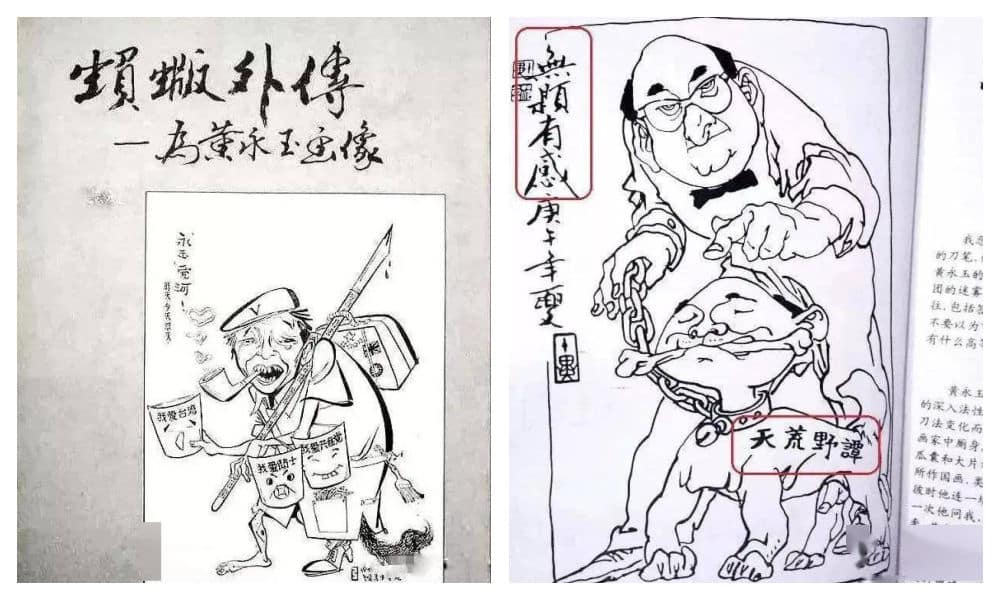

Another source of dislike stems from his history of disloyalty and his feud with another prominent Chinese painter, Huang Yongyu (黄永玉). Huang, who passed away in 2023, targeted Fan Zeng in some of his satirical paintings, including one titled “When Others Curse Me, I Also Curse Others” (“人骂我,我亦骂人”). He also painted a parrot, meant to mock Fan Zeng’s unoriginality.

Huang Yongyu made various works targeting Fan Zeng.

In retaliation, Fan produced his own works mocking Huang, sparking an infamous rivalry in the Chinese art world. The two allegedly almost had a physical fight when they ran into each other at the Beijing Hotel.

Fan Zeng mocked Huang Yongyu in some of his works.

Fan and Huang were once on good terms though, with Fan studying under Huang at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Through Huang, Fan was introduced to the renowned Chinese novelist Shen Congwen (沈从文, 1902-1988), Huang’s first cousin and lifelong friend. As Shen guided Fan in his studies and connected him with influential figures in China’s cultural circles, their relationship flourished.

However, during the Cultural Revolution, when Shen was accused of being a ‘reactionary,’ Fan Zeng turned against him, even going as far as creating big-character posters to criticize his former mentor.[2] This betrayal not only severed the bond between Shen and Fan but also ended Fan’s friendship with Huang, and it is still remembered by people today.

Fan Zeng’s behavior towards another former mentor, the renowned painter Li Kuchan (李苦禪, 1899-1983), was also controversial. Once Fan gained fame, he made it clear that he no longer respected Li as his teacher. Li later referred to Fan as “a wolf in sheep’s clothes,” and apparently never forgave him. Although the exact details of their falling out remain unclear, some blame Fan for exploiting Li to further his own career.

There are also some online commenters who call Fan Zeng a “Mr Wang from next door” (隔壁老王), a term jokingly used to refer to the untrustworthy neighbor who sleeps with one’s wife. This is mostly because of the history of how Fan Zeng met his third wife.

Fan’s first wife was the Chinese female calligrapher Lin Xiu (林岫), who came from a wealthy family. During this marriage, Fan did not have to worry about money and focused on his artistic endeavours. The two had a son, but the marriage ended in divorce after a decade. Fan’s second wife was fellow painter Bian Biaohua (边宝华), with whom he had a daughter. It seems that Bian loved Fan much more than he loved her.

It is how he met his third wife that remains controversial to this day. Nan Li (楠莉), formerly named Zhang Guiyun (张桂云), was married to performer Xu Zunde (须遵德). Xu was a close friend of Fan, and helped him out when Fan was still poor and trying to get by while living in Beijing’s old city center.

Wanting to support Fan’s artistic talent, Xu let Fan Zeng stay over, supported him financially, and would invite him for meals. Little did he know that while Xu was away to work, Fan enjoyed much more than meals alone; Fan and Xu’s wife engaged in a secret decade-long affair.

When the affair was finally exposed, Xu Zunde divorced his wife. Still, they would use his house to meet and often locked him out. Three years later, Nan Li officially married Fan Zeng. Xu not only lost his wife and friend but also ended up finding his house emptied, his two sons now bearing Fan’s surname.

When Nan Li passed away in 2021, Fan Zeng published an obituary that garnered criticism. Some felt that the entire text was actually more about praising himself than focusing on the life and character of his late wife, with whom he had been married for forty years.

Fan Zeng and his four wives

An ‘old pervert’, a ‘traitor’, a ‘disgrace’—there are a lot of opinions circulating about Fan that have come up this week.

Despite the negativity, a handful of individuals maintain a positive outlook. A former colleague of Xu Meng writes: “If they genuinely like each other, age shouldn’t matter. Here’s to wishing them a joyful marriage.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Song, Yuwu. 2014. Biographical Dictionary of the People’s Republic of China. United Kingdom: McFarland & Company, 76.

[2]Xu, Jilin. 2024. “Xu Jilin: Are Shen Congwen’s Tears Related to Fan Zeng?” 许纪霖:沈从文的泪与范曾有关系吗? The Paper, April 15. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_27011031. Accessed April 17, 2024.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

The Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight2 months ago

China Insight2 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 weeks ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 weeks ago“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

-

China Media2 months ago

China Media2 months agoParty Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

Markus Havemann

January 13, 2021 at 9:35 am

“Through the internet’s black market, she found someone who would pay 20,000 yuan ($3085) for it.”

Who buys a birth certificate and why and for so much money?

After all, the birth certificate states the name of the child and the parents, so it should be easy to track down the buyer once he presents the birth certificate at any official place. And then the certificate can be retransfered to the girl it belongs to… So it is more or less worthless for the buyer?