Backgrounder

50 of the Best New Books on China for the Holidays and Winter 2020/2021

So much reading to do! These are some of the best new books on China.

Published

4 years agoon

What’s on Weibo lists the 50 best China books for winter reading 2020/2021, with China non-fiction and fiction books that have come out in English recently.

What’s on Weibo has previously issued two major China book lists, one Best 30 Books to Understand Modern China (non-fiction), and one Top Best Fiction Books on China. Because both articles were published in 2018, and so many new and interesting books on China have come out since, it’s high time for another list.

This list consists of all new and interesting China books that have come out recently, mainly in 2020, but it also includes some earlier books.

We realize that there are so many books out there, and China’s domestic book market is enormous. But for the scope of this article, we will only list books that have come out in English as original works or were translated into English.

For the fiction section, we have selected modern fiction books by Chinese authors that have come out in English translation over the past two years. For a broader list of modern literary fiction works that provide deeper insights into China, please check our previous list here.

This list is categorized into seven major areas of China General (Popular), China History, Chinese Society & Focus Topics, China Tech/Digital, Academic Publications (China Studies), Chinese Fiction, and For Kids – something for everyone, from very broad China books to very focused subjects. Some books might fall into several categories such as academic and/or history, but have only been placed in one. Since there are many books being published on similar topics, we have tried to highlight different relevant focus topics and styles of narrating in this list. The order of the books is random and for reference purpose only (we do mention some personal favorites at the end of this list).

We have also tried to add relevant podcasts to each book recommendation, so there is plenty to read and listen to during these (pandemic) winter days!

ON CHINA GENERAL (POPULAR)

#1 ● Has China Won?: The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy

By Kishore Mahbubani, Public Affairs 2020

This book by the renowned Singaporean academic and former UN ambassador Kishore Mahbubani focuses on the geopolitical contest that has broken out between the US and China, and invites the reader to critically think about the complex dimensions behind this discourse and the strategic game behind it. Mahbubani writes that “it is curious that no one has pointed out that America is making a big strategic mistake by launching this contest with China without first developing a comprehensive and global strategy to deal with China” (2), and argues that not only does the US lack a sound understanding of its rival and their interests, it also overestimates its own position in a growingly complex international society. Being neither Chinese nor American, Kishore offers interesting perspectives that come from outside the American (or Chinese) thought bubble when it comes to current geopolitics.

Mahbubani is also on Twitter @mahbubani_k. Listen to the SupChina Sinica podcast with Kaiser Kuo featuring Kishore Mahbubani here.

Buy: Has China Won?: The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#2 ● China’s Western Horizon: Beijing and the New Geopolitics of Eurasia

By Daniel Markey, Oxford University Press 2020

With the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative being key to China’s present-day foreign policy, this list wouldn’t be complete without a book on this topic. Recently, multiple books came out on this subject. For example, there is The Emperor’s New Road: China and the Project of the Century by Jonathan Hillman and One Belt One Road: Chinese Power Meets the World by Eyck Freymann. One of the recent books on this topic to receive a lot of praise is that by China’s Western Horizon: Beijing and the New Geopolitics of Eurasia by Daniel Markey, senior research professor in International Relations at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. This book, useful for anyone who wants to get a better understanding of the Belt and Road Initiative, aims to make sense of “the decisive role that China’s less powerful neighbors are likely to play as China extends its reach across its western horizon.” This work is mainly divided into three sections, covering South Asia (chapter 3), Central Asia (chapter 4), and the Middle East (chapter 5). The last chapter focuses on US-China competition in Eurasia, with Markey arguing that the US needs a more local strategy in order to compete with China globally.

Listen to the Global Cable podcast with the author here. Daniel Markey is also on Twitter: @MarkeyDaniel.

Get the book here: China’s Western Horizon: Beijing and the New Geopolitics of Eurasia

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#3 ● Superpower Interrupted: The Chinese History of the World

By Michael Schuman, Public Affairs 2020

Superpower Interrupted offers a fresh perspective on China and its history for a western readership, focusing on the Chinese view of the Chinese history of the world, and demonstrating that there actually is no such thing as a truly global ‘world history.’ Schuman argues that since history shaped China’s perception of the world and its present-day position in international society, it is crucial for western diplomats, academics, politicians, and journalists to understand China not through the prism of their own world history, but through China’s own view.

Michael Schuman is also on Twitter: @MichaelSchuman. Sinica did a podcast with Schuman on his book earlier in 2020, which you can check out here.

Get: Superpower Interrupted: The Chinese History of the World

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#4 ● In the Dragon’s Shadow: Southeast Asia in the Chinese Century

By Sebastian Strangio, Yale University Press 2020

There is so much talk about US-China tensions recently, that China’s complicated relationships with its southern neighbors is a topic that often gets overlooked although it needs to be in the spotlight.In the Dragon’s Shadow, by journalist and Southeast Asia Editor at The Diplomat, is a very relevant work centering on the impact of China’s booming emergence and the dynamics of South East Asia. Chapter by chapter, Strangio provides valuable insights into the countries of Southeast Asia, exploring how China’s expanding power affects Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, Thailand, Burma, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines.

This book was recently featured on the Sinica podcast, with Kaiser Kuo saying the book “is easily one of the best books I’ve read this year.” Sebastian Strangio is also on Twitter: @sstrangio.

Buy: In the Dragon’s Shadow: Southeast Asia in the Chinese Century

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#5 ● India’s China Challenge: A Journey through China’s Rise

By Ananth Krishnan, HarperCollins India 2020

Ananth Krishnan, China correspondent for The Hindu, moved to China in the summer of 2008 and ended up staying a decade. This book is a result of the author’s own on-the-ground experiences, and, in an accessible and engaging way, presents different perspectives on what China’s rise and transformations mean for India. The book explores political, economic, diplomatic, and military challenges in China-India relations, and also zooms out to the broader implications for international society.

This book was featured on the Grand Tamasha podcast. Ananth Krishan is on Twitter @ananthkrishnan.

Get it here: India’s China Challenge: A Journey through China’s Rise

#6 ● China: The Bubble That Never Pops

By Thomas Orlik, Oxford University Press 2020

It will collapse, it will bounce back, financial crisis, yuan devaluation – so much has been written (and wrongly speculated) about China’s economy over the past decade or two that it is hard to believe anything you read anymore. One thing is clear, and that is that China’s economy has demonstrated resilience throughout the years. This resilience is at the heart of this book by Thomas Orlik, chief economist at Bloomberg. Orlik explores how China managed to escape national financial crises in the face of global slowdown and provides a clear overview of China’s economic history since Deng Xiaopeng. In doing so, the author makes it clear that conventional approaches often taken by Western analysts in looking at China’s economy often get it wrong – and he explains why.

China: The Bubble That Never Pops was featured on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast (link) and also on Sinica (link). Tom Orlik is on Twitter here: @TomOrlik.

Get: China: The Bubble that Never Pops

#7 ● Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise

By Scott Rozelle and Natalie Hell, University of Chicago Press 2020

This book by development economist Scott Rozelle and researcher Natalie Hell highlights problems that often remain invisible in the face of China’s rapid economic rise. It’s the drama of the rural low-educated workers who were the motor driving China’s growth since the 1980s, but are now more and more left jobless and hopeless in their home villages as low-skilled work is increasingly outsourced to other countries or is taken over by robotics. In many ways, China and the Chinese people are going forward – yet the rural population is left behind, and it’s China’s Achilles’ heel. This book focuses on this invisible side to China’s rise and on how such a big story, with such major implications, could be so little known.

More about this book here and in the World Class podcast here.

Get: Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise

#8 ● The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State

By Elizabeth C. Economy, Oxford University Press 2018

This book by Elizabeth Economy, Senior Fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, is for anyone who wants to understand how Xi’s ‘revolution’ is transforming China. It goes behind Xi Jinping and his vision for China, diving into the main areas on top of the Xi government agenda, including internal politics, the internet, innovation, economy, environment, and foreign policy. The priorities of the Xi-led leadership and the direction they are taking are not just of key importance to China, but also to the rest of the world – with a focus on the United States. A well-researched and concise work on China under Xi – its background, status-quo, and what lies ahead.

Elizabeth Economy is on Twitter, @LizEconomy. If you’d like to hear more on this book, listen to this CFR Asia Unbound podcast.

Get: The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

CHINA HISTORY

#9 ● China’s Good War: How World War II Is Shaping a New Nationalism

By Rana Mitter, Harvard University Press 2020

Rana Mitter is a British historian and political scientist who specializes in China’s history, and we’re a huge fan of his original perspectives and selection of topics. Mitter previously published China’s War with Japan, 1937-45: The Struggle for Survival (2014), which became an Economist Book of the Year and a Financial Times Book of the Year. For this book, Mitter continued to pursue his interest in China’s wartime history, this time focusing on how China’s memories of war have shaped its national identity, both at home and global role abroad. Mitter demonstrates that WWII is very much alive in China today, influencing popular culture and media to the dynamics of international relations.

Listen to Mitter talk about his book on the Sinica podcast here.

Get: China’s Good War: How World War II Is Shaping a New Nationalism

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

By Michael Wood, St Martin’s Press 2020

This brand-new single-volume work (624 pages) presents a chronological history of China, weaving personal, local stories into big historical narratives, from early history to modern-day China. Wood, Professor of Public History at the University of Manchester, previously wrote and presented the short documentary series for BBC and PBS that was also titled The Story of China. This is an excellent and accessible book for anyone with an interest in China’s history and its role in the world today.

Wood is on Twitter here @mayavision. More about his book in this South China Morning Post review.

Get: The Story of China: The Epic History of a World Power from the Middle Kingdom to Mao and the China Dream

★ Also available as audiobook via Audible here

#11 ● China at War: Triumph and Tragedy in the Emergence of the New China

By Hans van de Ven, Harvard University Press 2020

Hans van de Ven is Professor of Modern Chinese History at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of the British Academy. He specializes in the history of 19th and 20th century China. China at War zooms in on the period between 1937 and 1949. Van de Ven emphasizes that this was not just a time when China was at war with Japan, but also with itself, as it was also the time of the revolutionary war between the Nationalists and the Communists. The Second Sino-Japanese War and China’s civil war are intertwined and this history, and how it is remembered, is pivotal to understanding China’s 20th century and its place in the world today.

Check out the Asian Review of Books for more about China at War here. Hans van de Ven is also on Twitter @Jjv10Ven.

Get: China at War: Triumph and Tragedy in the Emergence of the New China

#12 ● Eurasian Crossroads – A History of Xinjiang

By James Millward, Hurst Publishers 2021 (2007)

This book ended up on our list here thanks to the ‘Five Best China Books 2020‘ article by Jeffrey Wasserstrom, American historian of modern China, who pointed out this upcoming renewed publication. The book was actually published years ago, but a new and revised edition is coming out in January 2021, adding a chapter on the status-quo in Xinjiang and the so-called re-education camps. With this book, James Millward, author and historian of China & Central Asia, provided the first comprehensive account in English of the history of Xinjiang and its peoples from earliest times to the present. This book is a must-have for anyone interested in Xinjiang and for anyone who wants to get a better grasp of the history and complex dynamics behind today’s Xinjiang.

There’s a recent episode of the Harvard Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies podcast featuring Millward speaking about the history of the crisis in the Uyghur Autonomous Region. James Millward is on Twitter @JimMillward.

Get (still the earlier version, updated book set to release late January 2021): Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang

#13 ● China and Japan: Facing History

By Ezra F. Vogel, Belknap Press of Harvard University 2019

Ezra F. Vogel, an eminent scholar of China and Japan, passed away in December of 2020. China and Japan: Facing History is his last book, which Vogel hoped would help improve understanding in that tense relationship between these neighboring rivals. With so many books focusing on China-US relations and power politics, there are relatively few new books that focus on Sino-Japanese relations, even though they are so crucial to both nations and the region. Vogel calls it a dangerous, deep, and complicated relationship. This book is an excellent overview of the relations between China and Japan, from early history to modern times.

The Harvard University Program on U.S.-Japan Relations recorded a podcast featuring Vogel earlier in 2020, which can be listened to here.

Get this book: China and Japan: Facing History

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#14 ● Maoism: A Global History

By Julia Lovell, Knopf 2019

This award-winning book is written by Julia Lovell, Professor of Modern Chinese History and Literature at Birkbeck College as well as an active translator of Chinese literature into English. Maoism: A Global History provides an overview of the influence of Maoism in different parts of the world from the 1930s to the present, with Lovell calling Maoism “one of the major stories of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.” This is a big book, but Lovell succeeds to captures the reader’s attention with her in-depth insights and engaging writing style.

Also check out this History Extra podcast, in which Julia Lovell explores the nature of Mao’s ideology and how it has shaped China and many other countries around the world.

Get: Maoism: A Global History

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#15 ● Last Boat Out of Shanghai: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Fled Mao’s Revolution

By Helen Zia, Ballantine Books 2019

Benny, Ho, Bing, and Annuo were still young when the Chinese civil war was coming to an end and the threat of a violent Communist revolution was looming over Shanghai, the epicenter of a large-scale exodus in the late 1940s. It is estimated that approximately one million people fled through the city around 1949, the year the People’s Republic of China was founded. Through the lens of the personal stories of some of these people, Zia shines a light on the bigger picture of the mass departure of wealthy and middle class Chinese and foreigners from Shanghai. She does so in a very captivating way – a pleasure to read.

In the They Call us Bruce podcast, Helen Zia talked about her book (link) and the tumultuous forces of history and migration. Helan Zia is also on Twitter here @HelenZiaReal.

Get: Last Boat Out of Shanghai: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Fled Mao’s Revolution

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#16 ● The Last Kings of Shanghai – The Rival Jewish Dynasties That Helped Create Modern China

By Jonathan Kaufman, Penguin Random House 2020

Shanghai’s Jewish history is a fascinating one, and over the past few years there’s been increased attention on the Jewish community of Shanghai and the history of Jews in China (also see our article on this, Memories of a Nearly Forgotten Community). In this book, author Jonathan Kaufman, journalist & director of the Northeastern University’s School of Journalism, tells the epic multigenerational stories of two Jewish families: Shanghai’s famous Sassoon family, who had been doing business in China for a century, and the Kadoorie family, another business dynasty that rivaled the Sassoons. Both the Sassoons and Kadoeries were originally from Baghdad, and these wealthy families accumulated great influence and played a role in Chinese business and politics for more than 175 years. This well-researched book provides intriguing insights into a history that few people know of.

In Northwestern University Library’s What’s New podcast, Kaufman recently discussed his book, link. Jonathan is on Twitter here @jkaufman617.

Get: The Last Kings of Shanghai: The Rival Jewish Dynasties That Helped Create Modern China

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#17 ● Forbidden Memory: Tibet during the Cultural Revolution

By Tsering Woeser, translated by Susan T Chen, edited by Robert Barnett, photographs by Tsering Dorje, Potomac Books 2020 (2006)

The story behind the making of the Forbidden Memory book is an extraordinary one. It begins with Tibetan writer and activist Tsering Woeser finding rare photos taken by her father, who passed away in 1991, of the Cultural Revolution period in Tibet. Woeser’s father, Tsering Dorje, was with the People’s Liberation Army when it entered Tibet in the 1950s. In 1999, Woeser sent these photos to Chinese writer and scholar Wang Lixiong, who had written on Tibet in his book Sky Burial: The Destiny of Tibet. Wang, realizing how precious these photographs were, wrote back to Woeser saying the history told through the photos needed to be told by herself and those on the inside of the history. Six years later, Woeser completed her research and writing, including interviews with over seventy people connected to the history captured in the photographs, and published an edition of Forbidden Memory for the Taiwanese market. Brought together by her father’s photos, Woeser and Wang ended up getting married in 2004. Now, in 2020, Forbidden Memory is finally translated into a revised English edition. Through text and photos, this 400-page book tells the horrible story of the violence of the Cultural Revolution in Tibet. With this work, Woeser uncovers the stories of a past that was previously erased.

Read more on this work here. Woeser is on Twitter here @degewa

Get: Forbidden Memory: Tibet during the Cultural Revolution

CHINESE SOCIETY AND FOCUS TOPICS

#18 ● Wuhan Diary: Dispatches from a Quarantined City

By Fang Fang, translated by Michael Berry, HarperCollins 2020

Wuhan Diary is written by the 65-year-old acclaimed Chinese author Wang Fang, better known as Fang Fang, and it is an important book documenting China’s COVID19 outbreak. Wuhan Diary is an online account of the 2020 Hubei lockdown, originally published on WeChat and Weibo. Throughout the lockdown period in January, February, and March, Fang Fang wrote about life in quarantine in province capital Wuhan, the heart of the epicenter, documenting everything from the weather to the latest news and the personal stories and tragedies behind the emerging crisis. Fang’s 60-post diary was published on her Weibo account from late January shortly after the lockdown began, until late March when the end of the lockdown was announced. Although Fang was originally praised as a ‘voice of the people’ in China, she was later bashed for being a ‘traitor’ once it became known that her book would be published in the US and Europe.

Read more about Wuhan Diary and its controversy here.

Get: Wuhan Diary: Dispatches from a Quarantined City

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#19 ● Eat the Buddha: Life and Death in a Tibetan Town

By Barbara Demick, Random House 2020

American journalist Barbara Demick previously wrote a book on North Korea (Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea) (2010), and with this book she explores another closed-off area; that of Sichuan’s Ngaba, a place that is usually a no-go area for foreign journalists due to the many anti-government demonstrations and self-immolation protesters. During the years she lived in China, Demick managed to travel to Ngaba on several occasions and conducted interviews. This book is a result of these interviews and spans decades of modern Tibetan and Chinese history and closely examines the relationships between the Chinese Communist Party and Tibet.

Demick is on Twitter @BarbaraDemick.

Get: Eat the Buddha: Life and Death in a Tibetan Town

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#20 ● City on Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong

By Antony Dapiran, Scribe 2020

This list obviously needs a focus book on Hong Kong, as 2020 came with great restrictions on Hong Kong freedom as the National Security Law came into effect – causing alarm among the people that have protested for greater freedom, democracy, and independence from the political influences of Beijing since 2019. In this book, Hong Kong-based lawyer and author Antony Dapiran provides a concise account of the Hong Kong’s 2019 anti-government protests that grew into a pro-democracy movement that engulfed the city for months. This book is for everyone who wants to understand what has happened and is happening in Hong Kong and grasp the protesters’ tactics and how their movement fits into the city’s history of dissent.

Listen to more on this book in the Intelligence Squared podcast here. Anthony is on Twitter here @antd.

Get: City on Fire: the fight for Hong Kong

#21 ● The Myth of Chinese Capitalism: The Worker, the Factory, and the Future of the World

By Dexter Roberts, St Martin’s Press 2020

There are many complicated stories behind all the headlines on China’s economic success and its rise on the world stage. This book by award-winning journalist Dexter Robers sheds critical light on the serious problems that China and its people face today; (reverse) migration, an aging society, income inequality, an unfair hukou system, and rising social unrest. Roberts tells the stories of the people behind these huge issues, focusing on the small village of Binghuacun in Guizhou and on Dongguan town in Guangdong.

Roberts and his work recently came on the Sinica podcast, listen here. Dexter Roberts is on Twitter here @dtiffroberts.

Get the book: The Myth of Chinese Capitalism: The Worker, the Factory, and the Future of the World

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#22 ● The Chile Pepper in China: A Cultural Biography

By Brian Dott, Columbia University Press 2020

The Chile Pepper in China is just too hot to exclude from this list. In this book, Brian Dott, associate professor of history at Whitman College, explores the evolution of the chile pepper from an obscure foreign import to a ubiquitous plant regarded by most Chinese as native to the land. In doing so, we learn many new things. Such as that there were no chiles anywhere in China prior to the 1570s – which is surprising when you know how firmly chile is ingrained in China’s national and local gastronomic traditions. The chile serves as a lens through with Dott explains more about Chinese history and the changing components of Chinese culture.

Brian Dott and his recent work were previously featured on the Sinica podcast here.

#23 ● Beijing from Below: Stories of Marginal Lives in the Capital’s Center

By Harriet Evans, Duke University Press 2020

Anyone who has been to Beijing pre-Olympics and after will understand the major transformation some parts of the city have undergone during and since that time. This book by Harriet Evans, Emeritus Professor of Chinese Cultural Studies at the University of Westminster, focuses on the disadvantaged residents of ‘Dashalar’, a small popular neighborhood just steps away from Tiananmen. It is the result of years-long research between 2007-2014 and conversations with its old residents, and captures how the rapid pace of Beijing’s transformation is affecting local families and individuals.

Listen to Harriet Evans speak about her work and Beijing in this podcast by New Books in Anthropology.

Get this book: Beijing from Below: Stories of Marginal Lives in the Capital’s Center

#24 ● China’s New Red Guards: The Return of Radicalism and the Rebirth of Mao Zedong

By Jude Blanchette, Oxford University Press 2019

China’s neo-Maoists are those who place their belief in that the philosophy and strategies of Mao Zedong can help China navigate the 21st century. In this book, Blanchette zooms in on neo-Maoism as a political movement born out of discontent with China’s current-day political and economic route. Besides shedding light on China’s political system and how the political agenda has shifted since Mao’s death, China’s New Red Guards explores key questions of who speaks for ‘authentic socialism’ and Marxism, “and who the true political inheritors of Mao’s legacy are.”

Kaiser Kuo sat down with Jude Blanchette for the Sinica podcast here.

Get: China’s New Red Guards: The Return of Radicalism and the Rebirth of Mao Zedong

# 25 ● Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister: Three Women at the Heart of Twentieth-Century China

By Jung Chang, Vintage Digital 2019

Jung Chang is most famous for her work Wild Swans, a classic book that virtually anyone who is interested in China will probably have in their book collection. Although Jung Chang previously drew criticism over Mao: The Untold Story, with people questioning the factual accuracy, this new book needs to be here due to its fascinating topic of three sisters who part of a defining moment in China’s modern history as sisters, wives, and mothers. The Song sisters, born between 1888 and 1898, were all powerful and influential women, with each choosing their own unique path. Ailing became a successful businesswoman in cooperation with her husband (a director of the Bank of China), Qingling married Sun Yat-sen, and Meiling married Chiang Kai-shek. In Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister, Jung Chang goes beyond the popular generalizations about the Song sisters (“one loves power, one loves money, one loves the people”), and tells their stories in an absorbing way and highlights the tensions between them. Fun fact: Jung Chang initially planned to write a book about Sun Yat-sen but then decided his wife and her sisters were far more interesting.

For more on Jung Chang’s latest work, check out this episode of the Spectator Books podcast.

Get: Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister: Three Women at the Heart of Twentieth-Century China

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

CHINA TECH & DIGITAL

#26 ● Attention Factory: The Story of TikTok and China’s ByteDance

By Matthew Brennan, 2020

China’s ‘old’ tech giants Baidu, Alibaba en Tencent are often at the center of books that focus on China’s flourishing tech scene, but it is high time that the newer giants get the attention they deserve. Brennan’s book focuses on Bytedance, the company behind super-popular apps such as TikTok, Toutiao, and Xigua. He tells the story of the company’s rise to international fame, with TikTok becoming the most downloaded app in the world in 2020. Brennan explains both the ‘back end’ and the ‘front end’ – shining a light on TikTok’s algorithms, business growth stages, telling the story of Bytedance founder Zhang Yiming and the early years of the company. In doing so, Brennan clearly illustrates the road that has led to TikTok’s emergence as a global hit.

Listen to the FYI Podcast with Brennan here. Follow Matthew Brennan on Twitter here @mbrennanchina.

Get the book here: Attention Factory: The Story of TikTok and China’s ByteDance

(Also available on BookDepository)

#27 ● Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in China’s Countryside

By Xiaowei Wang, Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2020

China’s rapid technological developments are impacting virtually every corner of society. While mainstream media generally solely focus on how China’s urban people and environments are influenced by high-tech innovation, Blockchain Chicken Farm puts a spotlight on how the lives of China’s rural and poor are changed by technology. In this book, technologist and writer Xiaowei Wang challenges metronormativity and shows that China’s countryside is not just adapting to the rapid technological developments – it is fuelling the technology that’s used every day. From AI farming systems to e-commerce villages and blockchain food projects, Wang provides new insights into China’s tech world, its urban-rural dynamics, and globalization.

Xiaowei Wang talks about their book in a recent episode of the ChinaTalk podcast with Jordan Schneider. Wang is also on Twitter @xrw.

Get: Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in China’s Countryside (FSG Originals x Logic)

#28 ● Censored: Distraction and Diversion Inside China’s Great Firewall

By Margaret E. Roberts, Princeton University Press 2020 (2018)

We can’t talk about China’s internet or digital environment at large without discussing its censorship apparatus. This work by Roberts zooms in on the dynamics of censorship in the Chinese digital environment and shows that China’s online censorship is not as black and white of an issue as it is sometimes made out to be. Censorship in China is ‘porous’, it is often circumventable, it includes some things and leaves out others. Roberts argues that there is a clear strategy behind this specific kind of censorship and how it differently affects different segments of the population.

Roberts talked about her work on the Sinica Podcast, listen here. Margaret Robers is also on Twitter @mollyeroberts.

Get the book: Censored: Distraction and Diversion Inside China’s Great Firewall

#29 ● The Great Firewall of China: How to Build and Control an Alternative Version of the Internet

By James Griffith, Zed Books 2019

This book by Griffith, reporter and producer for CNN International, is a great introduction to the background and history of the ‘Great Firewall of China’ and China’s online environment in general. Jumping from pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong and at Tiananmen to discussing Falun Gong and online Uyghur voices, Griffith narrates the story of China’s censorship machine in a compelling way.

Check The Wire China for more on this work, or check out ABC with Marc Fenell here. James is on Twitter here @jgriffiths.

Get the book: The Great Firewall of China: How to Build and Control an Alternative Version of the Internet

By Rebecca Fannin, Nicholas Brealey Publishing 2019

It is always a bit hard to recommend books on the ongoing tech developments in China, since they tend to be outdated from the moment they are published. Still, this book by Rebecca Fannin (who previously wrote Silicon Dragon) is an informative starting point for those who need an introduction to China’s tech environment, its main players, and most important startups. It explains how and why Chinese tech players and products have become more innovative than their American counterparts, and how they quickly invest and commercialize.

The Inside Asia podcast previously featured Fannin and her book in this episode. Rebecca Fannin is also on Twitter @rfannin.

Get the book here: Tech Titans of China: How China’s Tech Sector is challenging the world by innovating faster, working harder, and going global

#31 ● AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order

By Kai-Fu Lee, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2018

This best-selling book by computer scientist and businessman Kai-Fu Lee is often highly recommended within China’s tech book category because it gives a clear overview of the country’s artificial intelligence industry and how China’s status-quo as AI superpower and ongoing ‘AI fever’ will have dramatic implications for global economics and governance. Informative and engaging, this book provides valuable insights into China and AI in general, and the challenges that lie ahead.

Listen to Kai-fu Lee talk about his book on the Lex Fridman podcast here. Kai-Fu Lee is also on Twitter @kaifulee.

Get the book: AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#32 ● China, Africa, and the Future of the Internet

By Iginio Gagliardone, Zed Books 2020

Chinese presence in Africa is an important focus topic that definitely needs to be included on this list, and Gagliardone’s book provides an original and relevant perspective. It examines the extent to which China is influencing information societies in Africa, where the Internet, in various ways, is still taking shape. Gagliardone explores the existing assumption that China is influencing other media systems and is actively promoting its own model of a controlled Internet environment outside of the PRC. Gagliardone makes it clear that African states are not passive recipients of Chinese influence and highlights the complex dynamics of Chinese-African relations and the Internet.

Check out this episode of the China in Africa podcast featuring this author on this latest book. Iginio Gagliardone is also on Twitter @iginioe.

Get the book: China, Africa, and the Future of the Internet

IN CHINA STUDIES

#33 ● The Chinese Communist Party in Action: Consolidating Party Rule

By Zheng Yongnian and Lance L.P. Gore (eds), Routledge 2020

There is a lot of talk about China’s ‘One Party system’ and the Communist Party, with many being unaware of the systems and dynamics behind the CCP. This edited volume explores the role of the Chinese Communist Party as an institution in China today; its strategies, its campaigns, transformations, the interaction between party members, and its policymaking. These thirteen chapters are written by different scholars from various parts of the world.

Get this book: The Chinese Communist Party in Action: Consolidating Party Rule (China Policy Series)

#34 ● Afterlives of Chinese Communism: Political Concepts from Mao to Xi

Christian Sorace, Ivan Francescini, Nicholas Loubere (eds), Verso Book 2019

What is the legacy of the Mao era? There is no straightforward answer to this question. This edited volume is a collection of essays discussing the history and contemporary relevance of key concepts from the Mao era. It focuses on the political thoughts and discourse in China from 1949-1976 and revisits the complicated and contested legacies of Chinese communism, with each author in this work writing about this topic from their own critical perspective.

Get: Afterlives of Chinese Communism: Political Concepts from Mao to Xi

#35 ● Anxious China – Inner Revolution and Politics of Psychotherapy

By Li Zhang, University of California Press 2020

We first learned about this book via the New Books in East Asian Studies podcast and wanted to include it here due to its original and relevant research on how Chinese middle-class urbanites are more and more turning to Western-style counseling to deal with psychological distress in a rapidly changing China. Li Zhang is a Professor of Anthropology at the University of California at Davis. She argues that China’s profound economic reforms have not just generated transformations in China’s society and urban landscape, but have also generated changes the inner landscape of people in China. Li speaks of ‘a new kind of revolution’ unfolding in postsocialist China, which she terms “the inner revolution.” This book provides valuable insights into the field of psychology in China today and contextualizes the emergence of a new language entering China – allowing people to talk about their emotional distress despite the existing stigmas on mental health.

Listen to the New Books Network here.

Get this book: Anxious China: Inner Revolution and Politics of Psychotherapy

#36 ● China and the World

By David Shambaugh (ed), Oxford University Press 2020

This well-organized volume edited by Professor David Shambaugh consists of sixteen chapters by renowned China scholars from various countries with different academic specialties to describe China’s developments to date, focusing on its foreign relations and role on the world stage today. Some examples: renowned Norwegian historian Odd Arne Westad provides an insightful chapter of how China’s past matters to its present-day foreign affairs (chapter 2); founding director of the Manchester China Institute Peter Gries ties Chinese foreign policy to nationalism and social influences in chapter 4; Robert Sutter, one of America’s most respected scholars of Chinese foreign policy, writes about Sino-US relations in chapter 10.

Get this book: China and the World

#37 ● Securing China’s Northwest Frontier: Identity and Insecurity in Xinjiang

By David Tobin, Cambridge University Press 2020

Analysis of Chinese nationalism is often focused on the construction of the West and Japan as threats, but in this work, Tobin argues that the position of ‘domestic strangers’ is crucial to understanding nationalism in present-day China. Tobin analyzes how nation-building in China’s western Xinjiang region had shaped and is shaping insecurity and ethnic boundaries between Han and Uyghur populations.

While we’re here, we’d like to sneak another recommendation, namely Land of Strangers: The Civilizing Project in Qing Central Asia by Eric Schluessel, social historian of China and Central Asia (Twitter @EricTSchluessel). Land of Strangers explores the ‘civilizing mission’ in Xinjiang undertaken in the last decades of the Qing to transform Xinjiang’s Turkic-speaking Muslims into Chinese-speaking Confucian.

Listen to the New Books Network podcast with Tobin here. David Tobin is on Twitter @ReasonablyRagin.

Get the book: Securing China’s Northwest Frontier: Identity and Insecurity in Xinjiang

And also: Land of Strangers: The Civilizing Project in Qing Central Asia

#38 ● Staging China: The Politics of Mass Spectacle

By Florian Schneider, Leiden University Press 2019

Florian Schneider, social scientist and China-scholar at the Leiden University Institute of Area Studies and director of the Leiden Asian Center, previously published Visual Political Communication in Popular Chinese Television Series and China’s Digital Nationalism. This book deals with large-scale staged events in mainland China and dives deeper into the discourse of power and media politics behind them. The Shanghai Expo, the Beijing Olympics opening ceremony and the PRC anniversary parade are among the high-profile spectacles analyzed by Schneider as vehicles through which China’s leadership communicates its ideologies to the people. This work is interesting for anyone in China studies interested in media, propaganda, and politics, but also for those outside of China studies who would like to get a better understanding of visual political communication and discourse analysis.

Florian Schneider is on Twitter @schneiderfa77.

Get this book: Staging China: The Politics of Mass Spectacle

#39 ● The Other Digital China: Nonconfrontational Activism on the Social Web

By Jing Wang, Harvard University Press 2019

In present-day China, there is a large group of social media users and agents who are finding ways to express discontent online without directly confronting state authority. Jing Wang, a scholar at MIT and an activist in China, argues that there are many ways in which online activism is taking place in China’s social media environment – yet there is often a onedimensional of Chinese activism and social media users as if they’re either ‘brainwashed’ or ‘dissidents.’ In this work, Jing shows the multidimensionality of activism on the Chinese internet and tracks its transformations.

Get via Amazon: The Other Digital China: Nonconfrontational Activism on the Social Web

CHINESE FICTION

#40 ● A Hero Born: The Definitive Edition (Legends of the Condor Heroes 1)

By Jin Yong, translated by Anna Holmwood,

Hong Kong martial arts novelist Louis Cha ‘Jin Yong’ (1924-2018) is probably the world’s most popular Chinese writer. His success is often compared to that of writers such as JRR Tolkien. His wuxia novels gave rise to their own entertainment industry, generating movies, TV adaptations, video games, and graphic novels. A Hero Born is the first book of Jin’s 12-volume epic Legends of the Condor Heroes, originally published in the late 1950s. Blending history and fantasy, the story is set in 13th-century China and follows the trials and tribulations of its hero, Guo Jing, from birth to adolescence.

Now – after just two of Jin Yong’s works were previously released in English translation – the entire Legends of the Condor Heroes series is being translated and published by MacLehose Press. A Hero Born is the first to have come out.

Get the book: A Hero Born: The Definitive Edition (Legends of the Condor Heroes, 1)

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#41 ● Stories of the Sahara

By Sanmao, translated by Mike Fu, 2020

The iconic author ‘Sanmao’ (real name Chen Maoping 陈懋平) was born in Chongqing, moved to Taiwan, studied in Spain, and settled in the Sahara. Decades after her death, Sanmao still has major appeal to social media users, who still post her quotes, photos, and audio segments on a daily basis. Although San Mao published her first book at the of 19, she did not really gain fame until the release of The Stories of the Sahara (撒哈拉的故事) in 1976, which became her most famous work. The book revolves around San Mao’s personal experiences in the Sahara desert together with her Spanish husband Jose Maria Quero Y Ruiz, whom San Mao lovingly called ‘He Xi’ (荷西) and with whom she spent six years in the desert.

Despite Sanmao’s celebrity status in China, none of her works had appeared in English translation. Until early 2020, when The Stories of the Sahara finally came out in English. The book consists of various essays, jumping back and forth over Sanmao’s time in the desert. Read more about Sanmao in our feature article here.

Get the book: Stories of the Sahara

#42 ● To Hold Up The Sky (Short Stories)

By Liu Cixin, 2020

This is a collection of over ten short stories by Liu Cixin, the same author as The Wandering Earth and The Three-Body Problem – the award-winning science fiction work that became a worldwide sensation and was called a “milestone in Chinese science-fiction” by The New York Times. Over the past few years, Liu has gained international fame for introducing “Chinese science fiction” to the world.

“What makes Chinese science fiction Chinese?”, Liu writes in his foreword: “For my part, I have never consciously or deliberately tried to make my sci-fi more Chinese. The stories in this anthology touch on a variety of sci-fi themes, but they all have something in common: They are about things that concern all of humanity, and the challenges and crises they depict are all things humanity faces together.”

Get the book: To Hold Up the Sky

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#43 ● Braised Pork

An Yu was born and raised in Beijing, and she left at the age of 18 to study at New York University. Braised Pork is her first novel, which revolves around Jia Jia who finds her husband drowned in their bathroom tub. The young window then sets out on a journey of self-discovery that takes her from whiskey bars to the high plains of Tibet. Along the way, she crosses paths with people experiencing losses of their own, including someone who may be able to offer her the love she had long thought impossible.

Braised Pork is an original debut, which Time called an “engrossing portrait of isolation.”

Get the book: Braised Pork: A Novel

★ Also available as audiobook (iTunes) here / or via Audible here

#44 ● Broken Wings

By Jia Pingwa, translated by Nicky Harman, 2019

Jia Pingwa is one of the most prominent names in contemporary Chinese literature. In Broken Wings, he focuses on rural China and the problem of human trafficking – China has one of the highest rates of human trafficking in the world. The novel centers on Butterfly, a young woman abducted and sold into a “marriage” in a mountainous village. The story follows her struggle to keep herself together while being imprisoned and abused.

Get: Broken Wings by Jia Pingwa

#45 ● Strange Beasts of China

By Yan Ge, translated by Jeremy Tiang, Tilted Axis Press 2020

In a fictional industrial Chinese town called Yong’an, an amateur cryptozoologist goes in search of marvelous spirits and monsters, some strongly resembling humans. Each chapter of Yan Ge’s novel introduces a new creature. While documenting the stories of the beasts of Yong’an, the cryptozoologist discovers more about herself.

#46 ● China Dream

By Ma Jian, translated by Flora Drew, 2018

Exiled author Ma Jian has written great works, including Red Dust, Stick Out Your Tongue, and Beijing Coma. His latest satirical work China Dream is about a corrupt senior official in a provincial Chinese city who struggles with his memories of the Cultural Revolution.

Get: China Dream

#47 ● Broken Stars: Contemporary Chinese Science Fiction in Translation

By Ken Liu (ed), Tor Books 2019

This volume contains sixteen short stories with a wide variety of styles from China’s groundbreaking science fiction writers, edited and translated by award-winning author Ken Liu.

Buy here: Broken Stars: Contemporary Chinese Science Fiction in Translation

FOR THE KIDS

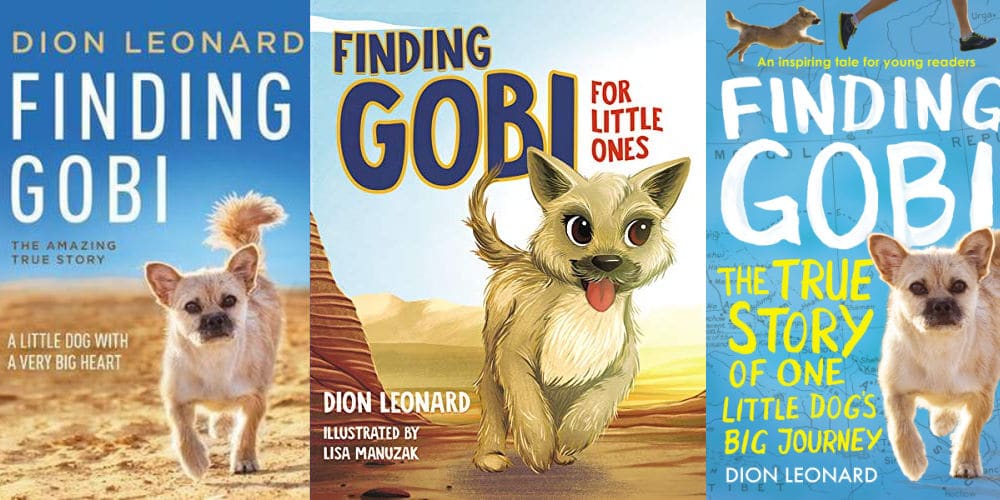

#48 ● Gobi: A Little Dog with a Big Heart

by Dion Leonard, illustrations by Liza Manuzak, 2017

In 2016, What’s on Weibo covered the story of the Australian runner Dion Leonard who found a best friend in a stray dog who joined him on his 155-mile marathon across China; the dog even stayed with the runner at night and never left his side. Determined to bring his loyal friend back home with him to the UK (Leonard is based in Edinburgh), Gobi started his lengthy quarantine process when the heartwarming story took a new turn for the worse: the little dog suddenly went missing in Urumqi. What followed was an intense search that was covered by all international media, and with dozes of Chinese volunteers ready to help and find this little dog in a city of 3,5 million people.

In Finding Gobi, Leonard tells the incredible story of this mission impossible that eventually had a happy ending that had everyone cheering. The book Finding Gobi – The True Story of a Little Dog and an Incredible Journey was published in 2017, and now there is also a children’s version and a picture board book for the littlest ones which makes a nice gift for kids who can read and then the youngest kids. (Tip for those studying Chinese! Finding Gobi was also translated into Chinese and came out in 2018. This book, 寻找 Gobi, is a fun read and suitable for upper-intermediate and advanced learners of Chinese.)

Get the book: Gobi: A Little Dog with a Big Heart (picture book)

Young Reader’s Edition (2017): Finding Gobi: Young Reader’s Edition: The True Story of One Little Dog’s Big Journey

Get the original edition (2017): Finding Gobi: A Little Dog with a Very Big Heart

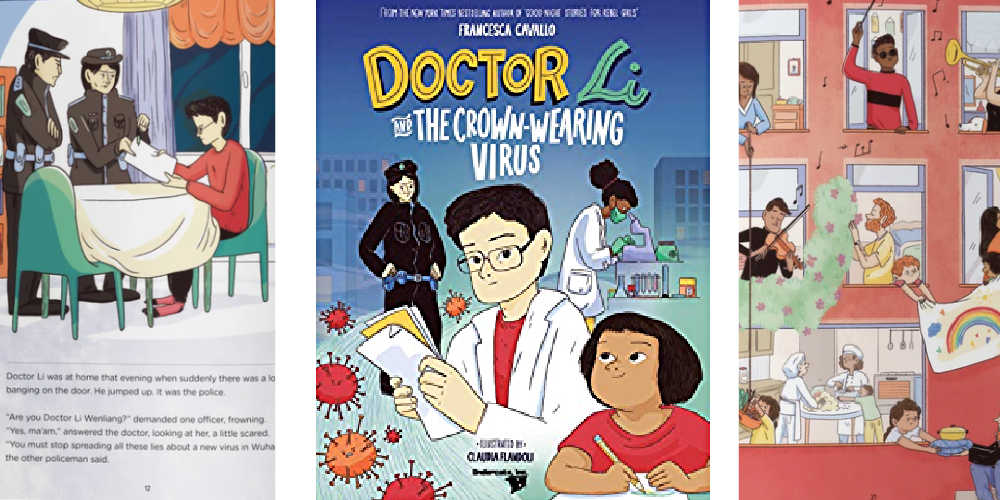

#49 ● Doctor Li and the Crown-Wearing Virus

By Francesca Cavallo, Undercats 2020

This children’s book was created to combat the rising Anti-Asian sentiment at the start of the pandemic. Writer Francesco Cavallo wanted to let kids around the world know that the first hero of the pandemic was a Chinese doctor named Doctor Li Wenliang who first raised the alarm that a novel coronavirus was spreading in Wuhan. This beautifully illustrated book is about a smart 7-year-old, May, who learns about Doctor Li’s courage and, inspired by his example, takes action in her community to cultivate hope, resilience and positivity through a difficult time.

Get: Doctor Li and the Crown-wearing Virus

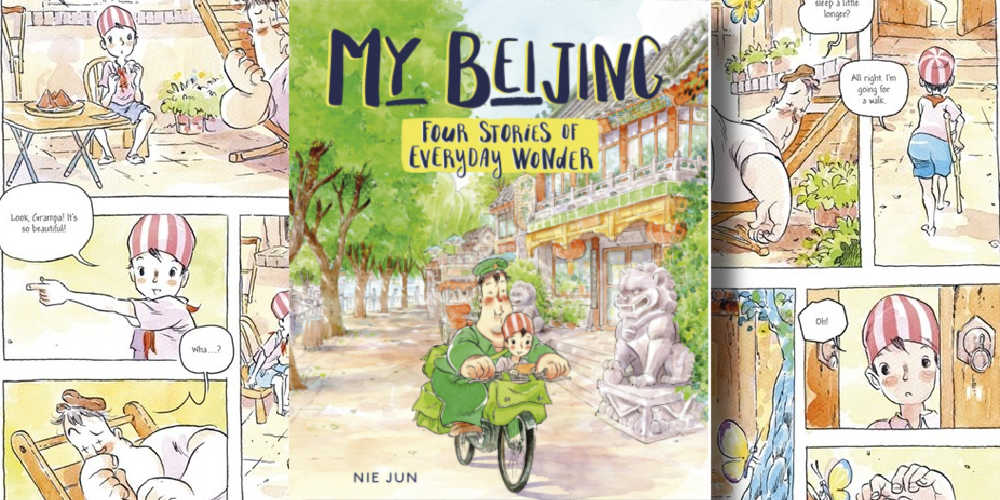

#50 ● My Beijing: Four Stories of Everyday Wonder

Story and illustration by Nie Jun, translation by Edward Gauvin, 2018

This is a graphic novel, a manga-style illustrated storybook, that follows little Beijing girl Yu’er and her grandpa. They live in a Beijing hutong neighborhood full of big personalities. There’s a story around every corner, and each day has a hint of magic. The book has some beautiful sketches that anyone who loves Beijing will appreciate – more than a comic book, this is a piece of art. Although the book is suitable for kids (age 7 and older), adults with a love for Beijing and its charming old neighborhoods will definitely also love this cute book.

Get it here: My Beijing: Four Stories of Everyday Wonder

There’s so much reading to do! Where to start?

There are many books in the list above focusing on many different topics, so it all depends on the areas you want to explore the most.

We’ll share some of our personal favorites.

They include Rana Mitter’s Good War and Helen Zia’s Last Boat out of Shanghai in the history section; Wang’s Blockchain Chicken Farm and Brennan’s Attention Factory in the tech category; Strangio’s In the Dragon’s Shadow and Roberts’ The Myth of Chinese Capitalism in the popular/focus sections, and lastly, Schneider’s Staging China and Wang’s The Other Digital China in the China Studies section.

EXTRA MENTIONS

We can’t fit them all in one list but we’d also really like to point out the following new books since they’re worth it!

● Inconvenient Memories – A Personal Account of the Tiananmen Square Incident and the China Before and After by Anna Wang, Purple Pegasus Inc 2019

● Hidden Hand: Exposing How the Chinese Communist Party is Reshaping the World, by Clive Hamilton and Mareike Ohlberg, Oneworld Publications 2020

● Mao’s Third Front: The Militarization of Cold War China by Covell F. Meyskens, Cambridge University Press 2020

● China’s Revolutions in the Modern World: A Brief Interpretive History by Rebecca E. Karl, Verso 2020

● Champions Day: The End of Old Shanghai, by James Carter, WW Norton & Co 2020

● The Book of Shanghai: A City in Short Fiction, Jin Li & Dai Congrong (eds), Comma Press 2020

● An American Bum in China: Featuring the Bumblingly Brilliant Escapades of Expatriate Matthew Evans, by Tom Carter, illustrations John Dobson, Camphor Press 2019

And lastly, we did not include travel books here, but for those planning to travel to China and looking for the right travel book:

● Travel to China: Everything You Need to Know Before You Go, by Josh Summers, edited by Leeanne Hendrick, Go West Media 2019

Happy reading!

By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

Enjoy this article and like to help keep What’s on Weibo going? Please consider donating to the site.

This is not a sponsored post. When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn a very small affiliate commission at zero extra cost to you – it helps us in maintaining this site. Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2020 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Backgrounder

“Oppenheimer” in China: Highlighting the Story of Qian Xuesen

Qian Xuesen is a renowned Chinese scientist whose life shares remarkable parallels with Oppenheimer’s.

Published

10 months agoon

September 16, 2023By

Zilan Qian

They shared the same campus, lived in the same era, and both played pivotal roles in shaping modern history while navigating the intricate interplay between science and politics. With the release of the “Oppenheimer” movie in China, the renowned Chinese scientist Qian Xuesen is being compared to the American J. Robert Oppenheimer.

In late August, the highly anticipated U.S. movie Oppenheimer finally premiered in China, shedding light on the life of the famous American theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904-1967).

Besides igniting discussions about the life of this prominent scientist, the film has also reignited domestic media and public interest in Chinese scientists connected to Oppenheimer and nuclear physics.

There is one Chinese scientist whose life shares remarkable parallels with Oppenheimer’s. This is aerospace engineer and cyberneticist Qian Xuesen (钱学森, 1911-2009). Like Oppenheimer, he pursued his postgraduate studies overseas, taught at Caltech, and played a pivotal role during World War II for the US.

Qian Xuesen is so widely recognized in China that whenever I introduce myself there, I often clarify my last name by saying, “it’s the same Qian as Qian Xuesen’s,” to ensure that people get my name.

Some Chinese blogs recently compared the academic paths and scholarly contributions of the two scientists, while others highlighted the similarities in their political challenges, including the revocation of their security clearances.

The era of McCarthyism in the United States cast a shadow over Qian’s career, and, similar to Oppenheimer, he was branded as a “communist suspect.” Eventually, these political pressures forced him to return to China.

Although Qian’s return to China made his later life different from Oppenheimer’s, both scientists lived their lives navigating the complex dynamics between science and politics. Here, we provide a brief overview of the life and accomplishments of Qian Xuesen.

Departing: Going to America

Qian Xuesen (钱学森, also written as Hsue-Shen Tsien), often referred to as the “father of China’s missile and space program,” was born in Shanghai in 1911,1 a pivotal year marked by a historic revolution that brought an end to the imperial dynasty and gave rise to the Republic of China.

Much like Oppenheimer, who pursued further studies at Cambridge after completing his undergraduate education, Qian embarked on a journey to the United States following his bachelor’s studies at National Chiao Tung University (now Shanghai Jiao Tong University). He spent a year at Tsinghua University in preparation for his departure.

The year was 1935, during the eighth year of the Chinese Civil War and the fourth year of Japan’s invasion of China, setting the backdrop for his academic pursuits in a turbulent era.

Qian in his office at Caltech (image source).

One year after arriving in the U.S., Qian earned his master’s degree in aeronautical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Three years later, in 1939, the 27-year-old Qian Xuesen completed his PhD at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), the very institution where Oppenheimer had been welcomed in 1927. In 1943, Qian solidified his position in academia as an associate professor at Caltech. While at Caltech, Qian helped found NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

When World War II began, while Oppenheimer was overseeing the Manhattan Project’s efforts to assist the U.S. in developing the atomic bomb, Qian actively supported the U.S. government. He served on the U.S. government’s Scientific Advisory Board and attained the rank of lieutenant colonel.

The first meeting of the US Department of the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board in 1946. The predecessor, the Scientific Advisory Group, was founded in 1944 to evaluate the aeronautical programs and facilities of the Axis powers of World War II. Qian can be seen standing in the back, the second on the left (image source).

After the war, Qian went to teach at MIT and returned to Caltech as a full-time professor in 1949. During that same year, Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Just one year later, the newly-formed nation became involved in the Korean War, and China fought a bloody battle against the United States.

Red Scare: Being Labeled as a Communist

Robert Oppenheimer and Qian Xuesen both had an interest in Communism even prior to World War II, attending communist gatherings and showing sympathy towards the Communist cause.

Qian and Oppenheimer may have briefly met each other through their shared involvement in communist activities. During his time at Caltech, Qian secretly attended meetings with Frank Oppenheimer, the brother of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Monk 2013).

However, it was only after the war that their political leanings became a focal point for the FBI.

Just as the FBI accused Oppenheimer of being an agent of the Soviet Union, they quickly labeled Qian as a subversive communist, largely due to his Chinese heritage. While the government did not succeed in proving that Qian had communist ties with China during that period, they did ultimately succeed in portraying Qian as a communist affiliated with China a decade later.

During the transition from the 1940s to the 1950s, the Cold War was underway, and the anti-communist witch-hunts associated with the McCarthy era started to intensify (BBC 2020).

In 1950, the Korean War erupted, with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) joining North Korea in the conflict against South Korea, which received support from the United States. It was during this tumultuous period that the FBI officially accused Qian of communist sympathies in 1950, leading to the revocation of his security clearance despite objections from Qian’s colleagues. Four years later, in 1954, Robert Oppenheimer went through a similar process.

The 1950’s security hearing of Qian (second left). (Image source).

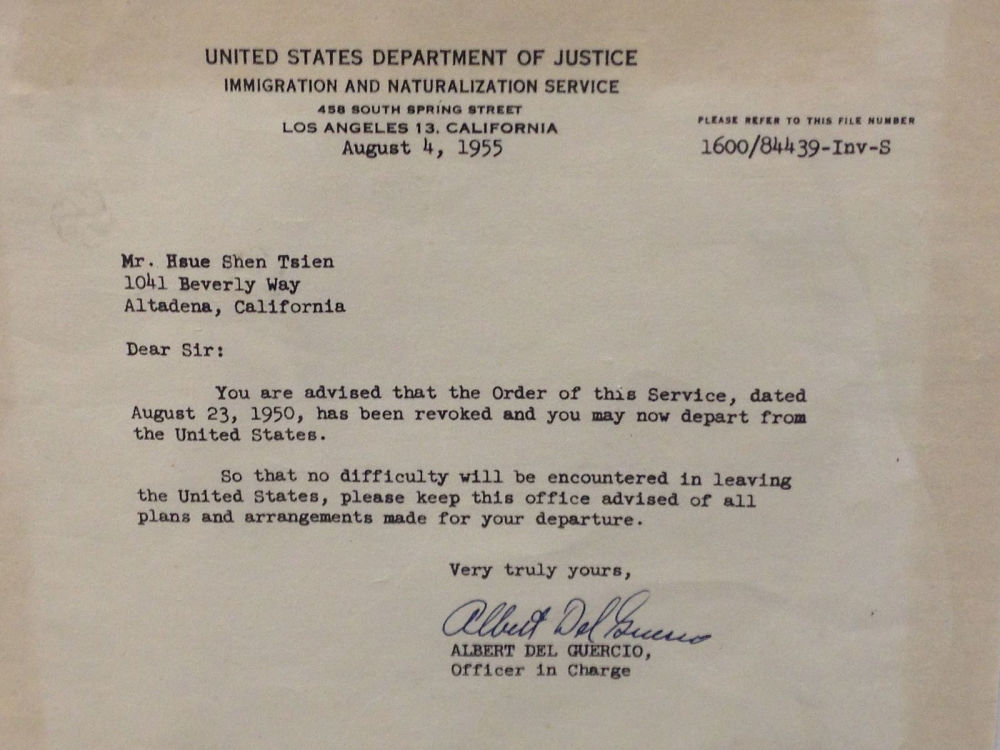

After losing his security clearance, Qian began to pack up, saying he wanted to visit his aging parents back home. Federal agents seized his luggage, which they claimed contained classified materials, and arrested him on suspicion of subversive activity. Although Qian denied any Communist leanings and rejected the accusation, he was detained by the government in California and spent the next five years under house arrest.

Five years later, in 1955, two years after the end of the Korean War, Qian was sent home to China as part of an apparent exchange for 11 American airmen who had been captured during the war. He told waiting reporters he “would never step foot in America again,” and he kept his promise (BBC 2020).

A letter from the US Immigration and Naturalization Service to Qian Xuesen, dated August 4, 1955, in which he was notified he was allowed to leave the US. The original copy is owned by Qian Xuesen Library of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, where the photo was taken. (Caption and image via wiki).

Dan Kimball, who was the Secretary of the US Navy at the time, expressed his regret about Qian’s departure, reportedly stating, “I’d rather shoot him dead than let him leave America. Wherever he goes, he equals five divisions.” He also stated: “It was the stupidest thing this country ever did. He was no more a communist than I was, and we forced him to go” (Perrett & Bradley, 2008).

Kimball may have foreseen the unfolding events accurately. After his return to China, Qian did indeed assume a pivotal role in enhancing China’s military capabilities, possibly surpassing the potency of five divisions. The missile programme that Qian helped develop in China resulted in weapons which were then fired back on America, including during the 1991 Gulf War (BBC 2020).

Returning: Becoming a National Hero

The China that Qian Xuesen had left behind was an entirely different China than the one he returned to. China, although having relatively few experts in the field, was embracing new possibilities and technologies related to rocketry and space exploration.

Within less than a month of his arrival, Qian was welcomed by the then Vice Prime Minister Chen Yi, and just four months later, he had the honor of meeting Chairman Mao himself.

Qian and Mao (image source).

In China, Qian began a remarkably successful career in rocket science, with great support from the state. He not only assumed leadership but also earned the distinguished title of the “father” of the Chinese missile program, instrumental in equipping China with Dongfeng ballistic missiles, Silkworm anti-ship missiles, and Long March space rockets.

Additionally, his efforts laid the foundation for China’s contemporary surveillance system.

By now, Qian has become somewhat of a folk hero. His tale of returning to China despite being thwarted by the U.S. government has become like a legendary narrative in China: driven by unwavering patriotism, he willingly abandoned his overseas success, surmounted formidable challenges, and dedicated himself to his motherland.

Throughout his lifetime, Qian received numerous state medals in recognition of his work, establishing him as a nationally celebrated intellectual. From 1989 to 2001, the state-launched public movement “Learn from Qian Xuesen” was promoted throughout the country, and by 2001, when Qian turned 90, the national praise for him was on a similar level as that for Deng Xiaoping in the decade prior (Wang 2011).

Qian Xuesen remains a celebrated figure. On September 3rd of this year, a new “Qian Xuesen School” was established in Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, becoming the sixth high school bearing the scientist’s name since the founding of the first one only a year ago.

In 2017, the play “Qian Xuesen” was performed at Qian’s alma mater, Shanghai Jiaotong University. (Image source.)

Qian Xuesen’s legacy extends well beyond educational institutions. His name frequently appears in the media, including online articles, books, and other publications. There is the Qian Xuesen Library and a museum in Shanghai, containing over 70,000 artefacts related to him. Qian’s life story has also been the inspiration for a theater production and a 2012 movie titled Hsue-Shen Tsien (钱学森).2

Unanswered Questions

As is often the case when people are turned into heroes, some part of the stories are left behind while others are highlighted. This holds true for both Robert Oppenheimer and Qian Xuesen.

The Communist Party of China hailed Qian as a folk hero, aligning with their vision of a strong, patriotic nation. Many Chinese narratives avoid the debate over whether Qian’s return was linked to problems and accusations in the U.S., rather than genuine loyalty to his homeland.

In contrast, some international media have depicted Qian as a “political opportunist” who returned to China due to disillusionment with the U.S., also highlighting his criticism of “revisionist” colleagues during the Cultural Revolution and his denunciation of the 1989 student demonstrations.

Unlike the image of a resolute loyalist favored by the Chinese public, Qian’s political ideology was, in fact, not consistently aligned, and there were instances where he may have prioritized opportunity over loyalty at different stages of his life.

Qian also did not necessarily aspire to be a “flawless hero.” Upon returning to China, he declined all offers to have his biography written for him and refrained from sharing personal information with the media. Consequently, very little is known about his personal life, leaving many questions about the motivations driving him, and his true political inclinations.

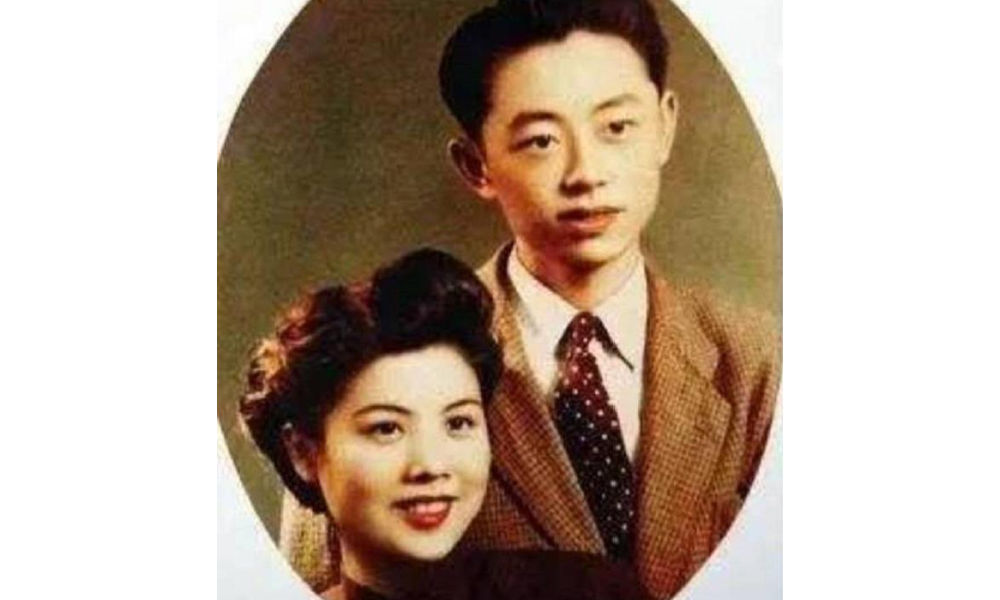

The marriage photo of Qian and Jiang. (Image source).

We do know that Qian’s wife, Jiang Ying (蒋英), had a remarkable background. She was of Chinese-Japanese mixed race and was the daughter of a prominent military strategist associated with Chiang Kai-shek. Jiang Ying was also an accomplished opera singer and later became a professor of music and opera at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing.

Just as with Qian, there remain numerous unanswered questions surrounding Oppenheimer, including the extent of his communist sympathies and whether these sympathies indirectly assisted the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Perhaps both scientists never imagined they would face these questions when they first decided to study physics. After all, they were scientists, not the heroes that some narratives portray them to be.

Also read:

■ Farewell to a Self-Taught Master: Remembering China’s Colorful, Bold, and Iconic Artist Huang Yongyu

■ “His Name Was Mao Anying”: Renewed Remembrance of Mao Zedong’s Son on Chinese Social Media

By Zilan Qian

Follow @whatsonweibo

1 Some sources claim that Qian was born in Hangzhou, while others say he was born in Shanghai with ancestral roots in Hangzhou.

2The Chinese character 钱 is typically romanized as “Qian” in Pinyin. However, “Tsien” is a romanization in Wu Chinese, which corresponds to the dialect spoken in the region where Qian Xuesen and his family have ancestral roots.

This article has been edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

References (other sources hyperlinked in text)

BBC. 2020. “Qian Xuesen: The man the US deported – who then helped China into space.” BBC.com, 27 October https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-54695598 [9.16.23].

Monk, Ray. 2013. Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center, First American Edition. New York: Doubleday.

Perrett, Bradley, and James R. Asker. 2008. “Person of the Year: Qian Xuesen.” Aviation Week and Space Technology 168 (1): 57-61.

Wang, Ning. 2011. “The Making of an Intellectual Hero: Chinese Narratives of Qian Xuesen.” The China Quarterly, 206, 352-371. doi:10.1017/S0305741011000300

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Backgrounder

Farewell to a Self-Taught Master: Remembering China’s Colorful, Bold, and Iconic Artist Huang Yongyu

Renowned Chinese artist and the creator of the ‘Blue Rabbit’ zodiac stamp Huang Yongyu has passed away at the age of 98. “I’m not afraid to die. If I’m dead, you may tickle me and see if I smile.”

Published

1 year agoon

June 15, 2023

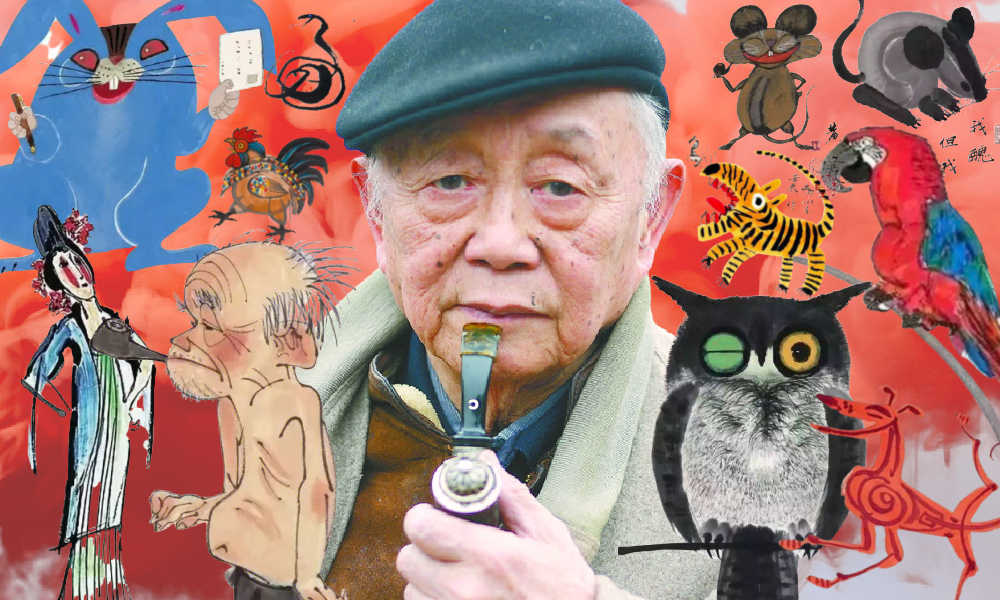

The famous Chinese painter, satirical poet, and cartoonist Huang Yongyu has passed away. Born in 1924, Huang endured war and hardship, yet never lost his zest for life. When his creativity was hindered and his work was suppressed during politically tumultuous times, he remained resilient and increased “the fun of living” by making his world more colorful.

He was a youthful optimist at old age, and will now be remembered as an immortal legend. The renowned Chinese painter and stamp designer Huang Yongyu (黄永玉) passed away on June 13 at the age of 98. His departure garnered significant attention on Chinese social media platforms this week.

On Weibo, the hashtag “Huang Yongyu Passed Away” (#黄永玉逝世#) received over 160 million views by Wednesday evening.

Huang was a member of the China National Academy of Painting (中国国家画院) as well as a Professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (中央美术学院).

Huang Yongyu is widely recognized in China for his notable contribution to stamp design, particularly for his iconic creation of the monkey stamp in 1980. Although he designed a second monkey stamp in 2016, the 1980 stamp holds significant historical importance as it marked the commencement of China Post’s annual tradition of releasing zodiac stamps, which have since become highly regarded and collectible items.

Huang’s famous money stamp that was issued by China Post in 1980.

The monkey stamp designed by Huang Yongyu has become a cherished collector’s item, even outside of China. On online marketplaces like eBay, individual stamps from this series are being sold for approximately $2000 these days.

Huang Yongyu’s latest most famous stamp was this year’s China Post zodiac stamp. The stamp, a blue rabbit with red eyes, caused some online commotion as many people thought it looked “horrific.”

Some thought the red-eyed blue rabbit looked like a rat. Others thought it looked “evil” or “monster-like.” There were also those who wondered if the blue rabbit looked so wild because it just caught Covid.

Huang’s (in)famous blue rabbit stamp.

Nevertheless, many people lined up at post offices for the stamps and they immediately sold out.

In light of the controversy, Huang Yongyu spoke about the stamps in a livestream in January of 2023. The 98-year-old artist claimed he had simply drawn the rabbit to spread joy and celebrate the new year, stating, “Painting a rabbit stamp is a happy thing. Everyone could draw my rabbit. It’s not like I’m the only one who can draw this.”

Huang’s response also went viral, with one Weibo hashtag dedicated to the topic receiving over 12 million views (#蓝兔邮票设计者直播回应争议#) at the time. Those defending Huang emphasized how it was precisely his playful, light, and unique approach to art that has made Huang’s work so famous.

A Self-Made Artist

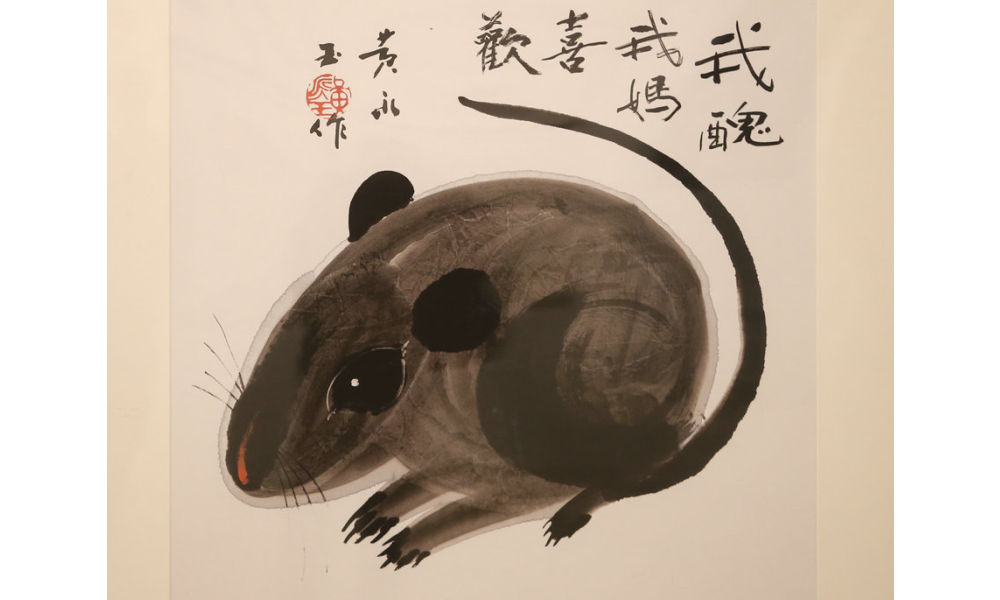

“I’m ugly, but my mum likes me”

‘Ugly Mouse’ by Huang Yongyu [Image via China Daily].

Huang Yongyu was born on August 9, 1924, in Hunan’s Chengde as a native of the Tujia ethnic group.

He was born into an extraordinary family. His grandfather, Huang Jingming (黄镜铭), worked for Xiong Xiling (熊希齡), who would become the Premier of the Republic of China. His first cousin and lifelong friend was the famous Chinese novelist Shen Congwen (沈从文). Huang’s father studied music and art and was good at drawing and playing the accordion. His mother graduated from the Second Provincial Normal School and was the first woman in her county to cut her hair short and wear a short skirt (CCTV).

Born in times of unrest and poverty, Huang never went to college and was sent away to live with relatives at the age of 13. His father would die shortly after, depriving him of a final goodbye. Huang started working in various places and regions, from porcelain workshops in Dehua to artisans’ spaces in Quanzhou. At the age of 16, Huang was already earning a living as a painter and woodcutter, showcasing his talents and setting the foundation for his future artistic pursuits.

When he was 22, Huang married his first girlfriend Zhang Meixi (张梅溪), a general’s daughter, with whom he shared a love for animals. He confessed his love for her when they both found themselves in a bomb shelter after an air-raid alarm.

Huang and Zhang Meixi [163.com]

In his twenties, Huang Yongyu emerged as a sought-after artist in Hong Kong, where he had relocated in 1948 to evade persecution for his left-wing activities. Despite achieving success there, he heeded Shen Congwen’s advice in 1953 and moved to Beijing. Accompanied by his wife and their 7-month-old child, Huang took on a teaching position at the esteemed Central Academy of Fine Arts (中央美术学院).

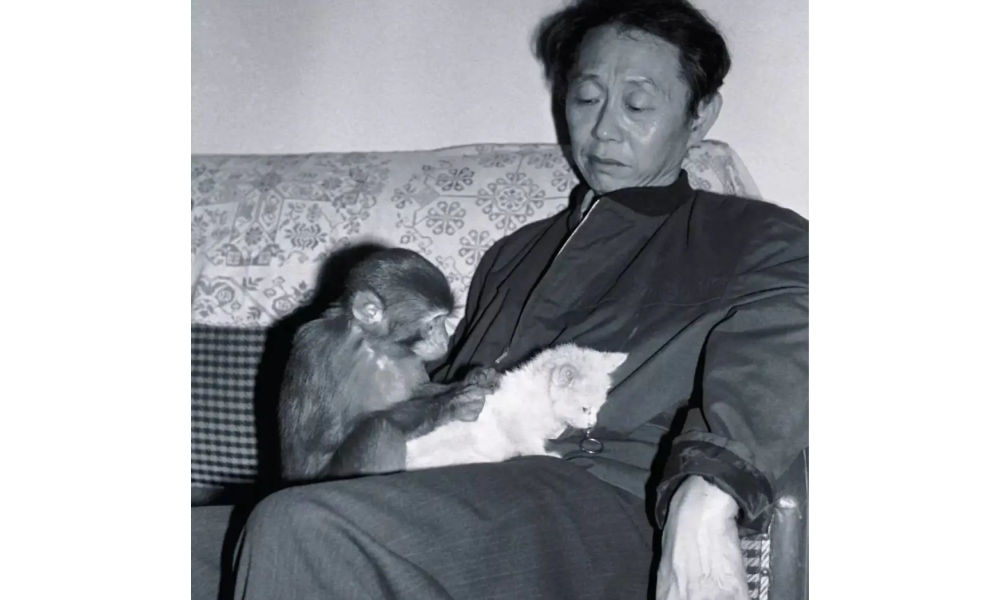

The couple raised all kinds of animals at their Beijing home, from dogs and owls to turkeys and sika deers, and even monkeys and bears (Baike).

Throughout Huang’s career, animals played a significant role, not only reflecting his youthful spirit but also serving as vehicles for conveying satirical messages.

One recurring motif in his artwork was the incorporation of mice. In one of his famous works, a grey mouse is accompanied by the phrase ‘I’m ugly, but my mum likes me’ (‘我丑,但我妈喜欢’), reinforcing the notion that regardless of our outward appearance or circumstances, we remain beloved children in the eyes of our mothers.

As a teacher, Huang liked to keep his lessons open-minded and he, who refused to join the Party himself, stressed the importance of art over politics. He would hold “no shirt parties” in which his all-male studio students would paint in an atmosphere of openness and camaraderie during hot summer nights (Andrews 1994, 221; Hawks 2017, 99).

By 1962, creativity in the classroom was limited and there were far more restrictions to what could and could not be created, said, and taught.

Bright Colors in Dark Times

“Strengthen my resolve and increase the fun of living”

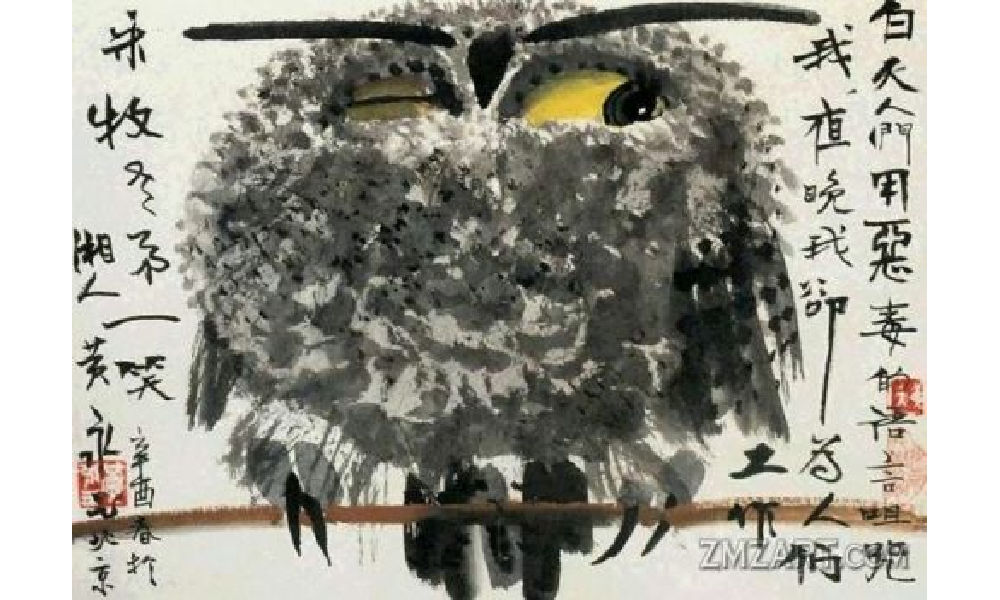

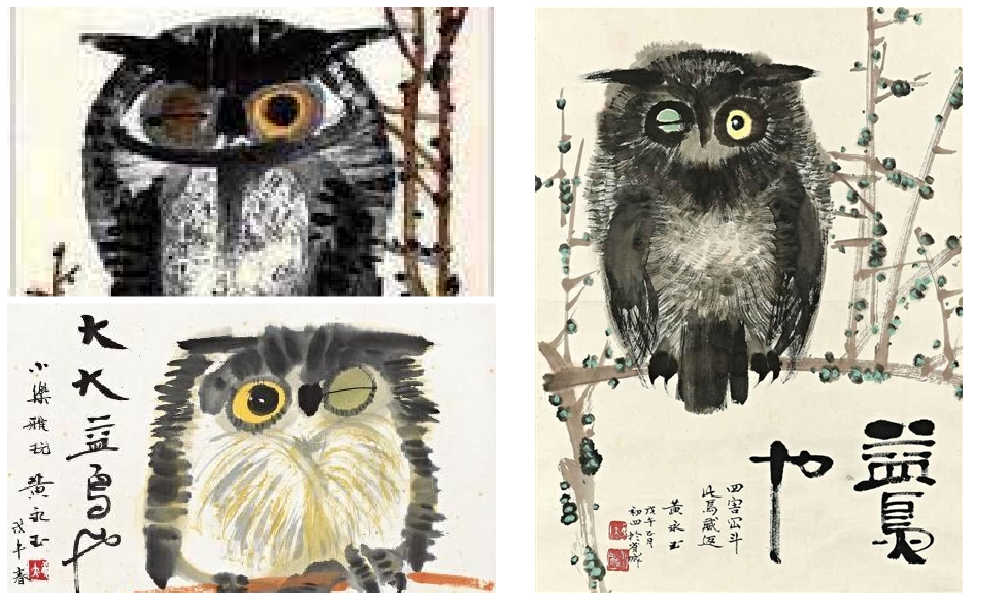

Huang Yongyu’s winking owl, 1973, via Wikiart.

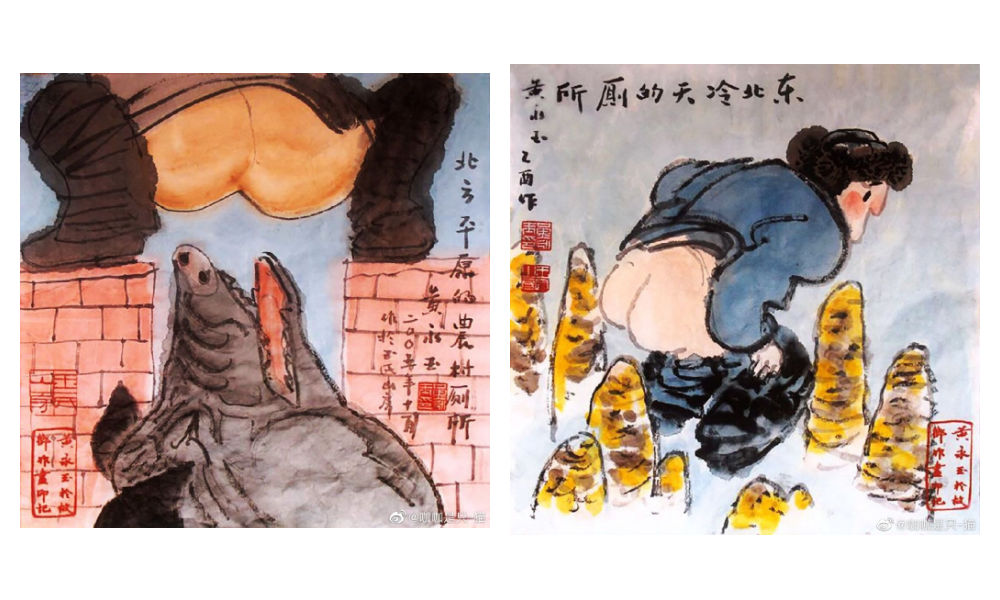

In 1963, Huang was sent to the countryside as part of the “Four Cleanups” movement (四清运动, 1963-1966). Although Huang cooperated with the requirement to attend political meetings and do farm work, he distanced himself from attempts to reform his thinking. In his own time, and even during political meetings, he would continue to compose satirical and humorous pictures and captions centered around animals, which would later turn into his ‘A Can of Worms’ series (Hawks 2017, 99; see Morningsun.org).

Three years later, at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, many Chinese major artists, including Huang, were detained in makeshift jails called ‘niupeng‘ (牛棚), cowsheds. Huang’s work was declared to be counter-revolutionary, and he was denounced and severely beaten. Despite the difficult circumstances, Huang’s humor and kindness would remind his fellow artist prisoners of the joy of daily living (2017, 95-96).

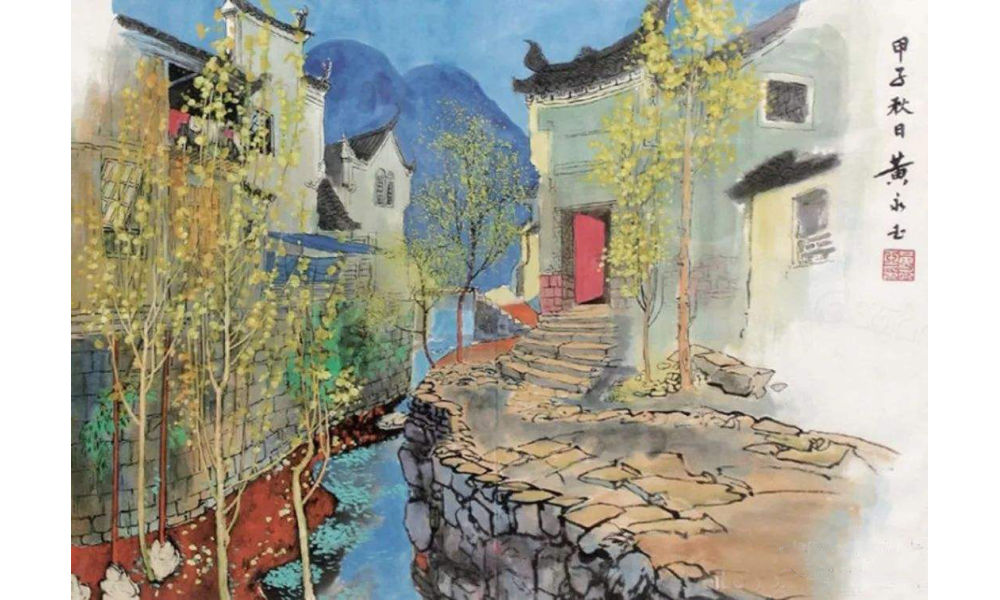

After his release, Huang and his family were relocated to a cramped room on the outskirts of Beijing. The authorities, thinking they could thwart his artistic pursuits, provided him with a shed that had only one window, which faced a neighbor’s wall. However, this limitation didn’t deter Huang. Instead, he ingeniously utilized vibrant pigments that shone brightly even in the dimly lit space.

During this time, he also decided to make himself an “extra window” by creating an oil painting titled “Eternal Window” (永远的窗户). Huang later explained that the flower blossoms in the paining were also intended to “strengthen my resolve and increase the fun of living” (Hawks 2017, 4; 100-101).

Huang Yongyu’s Eternal Window [Baidu].

In 1973, during the peak of the Cultural Revolution, Huang painted his famous winking owl. The calligraphy next to the owl reads: “During the day people curse me with vile words, but at night I work for them” (“白天人们用恶毒的语言诅咒我,夜晚我为他们工作”) (Matthysen 2021, 165).

The painting was seen as a display of animosity towards the regime, and Huang got in trouble for it. Later on in his career, however, Huang would continue to paint owls. In 1977, when the Cultural Revolution had ended, Huang Yongyu painted other owls to ridicules his former critics (2021, 174).

According to art scholar Shelly Drake Hawks, Huang Yongyu employed animals in his artwork to satirize the realities of life under socialism. This approach can be loosely compared to George Orwell’s famous novel Animal Farm.

However, Huang’s artistic style, vibrant personal life, and boundary-pushing work ethic also draw parallels to Picasso. Like Picasso, Huang embraced a colorful life, adopted an innovative approach to art, and challenged artistic norms.

An Optimist Despite All Hardships

“Quickly come praise me, while I’m still alive”

Huang Yongyu will be remembered in China with love and affection for numerous reasons. Whether it is his distinctive artwork, his mischievous smile and trademark pipe, his unwavering determination to follow his own path despite the authorities’ expectations, or his enduring love for his wife of over 75 years, there are countless aspects to appreciate and admire about Huang.

One things that is certainly admirable is how he was able to maintain a youthful and joyful attitude after suffering many hardships and losing so many friends.