China Insight

35 Facts About Chinese New Year

Chinese New Year has arrived. We are saying goodbye to the year of the Horse, and welcome the year of the Goat. Did you know that New Year was once cancelled by the government? Or that Xinjiang people receive “anti-extremist” New Year’s calendars? What’s on Weibo brings you 35 facts about Chinese New Year.

Published

9 years agoon

Chinese New Year has arrived. It is the most important Chinese festival of the year, and the anticipation starts weeks before it starts. Trending topics on Sina Weibo during this period include “going home”, “not able to go home”, “meeting the family-in-law” or “red envelope” (hongbao, monetary gifts during festivities). Did you know that Chinese New Year was once cancelled by the government? Or that Xinjiang people receive “anti-extremist” New Year’s calendars? What’s on Weibo brings you 35 facts about Chinese New Year.

1 * Chinese New Year has been celebrated for over 3000 years (Li 2006, ch.1).

2 * Chinese New Year is based on the lunar calendar, and begins on a different date every year; always in January or February. It lasts for fifteen days, until the night of the full moon. It usually falls near the first day of spring, hence it is also called the Spring Festival (Smith 2000).

3 * ‘Spending New Year’ in Chinese is ‘guo nian‘ (过年, nian meaning ‘year’). According to Chinese legend, the origins of Spring Festival can be found in the battle against the Nian, a fierce and hungry man-eating beast. Except for ‘spending New Year’, ‘guo nian‘ hence also means the ‘passing of the beast’.

4 * Except for the Han (China’s greatest ethnic group) Spring Festival is also celebrated by 38 other minorities (Li 2006, ch.1).

5 *Gong Xi Fa Cai (Mandarin) or Kung Hei Fat Choy (Cantonese) are the most common ways to say ‘Happy New Year’ in Chinese (恭喜发财).

6 * Fireworks are an integral part of Chinese New Year. Traditionally, the noise and fire is supposed to ward off evil spirits and bad luck.

7 * Due to worsening air pollution in China’s big cities over the past years, the enthusiasm for fireworks has curbed as the government has started anti-firework campaigns.

8 * 2015 is the Year of the Goat. It starts on February 19th and lasts until February 7th, 2016. Those with birth years 1907, 1919, 1931, 1943, 1955, 1967, 1979, 1991, 2003 and 2015 are said to have been born in the year of the Goat (Sabin 2015).

9 * The Chinese character for goat 羊 (yang) can mean either ram, sheep or goat- leading to much confusion on what kind of year this actually is. According to one Chinese linguist, the only right translation is goat: it is the goat that belongs in the Chinese zodiac, as it was one of the animals that was commonly eaten in ancient China, along with other zodiac signs such as horses, cows, dogs, pigs and chickens.

10 * The Year of the Goat is marked by positive changes. In terms of culture and arts it promises cool fashion, new styles and bright colors. In terms of politics, reconciliation plays an important role in the Year of the Goat. This will be a year for peace, dialogue and understanding (Sommerville 2014).

11 * The dragon dance is a form of traditional performance seen during the Chinese New Year. The dragon is believed to bring good luck. The Beijing Aquarium even holds underwater dragon dances.

12 * Ahead of the festivities, there is a mass exodus within China: 2.8 billion trips are made across the country so that people can go back to their hometowns to see friends and families to celebrate Chinese New Year together (Sabin 2015).

13 * Before the festival, people clean their house. They should not clean their house on the first two days of the New Year, as it is considered bad luck to “sweep away good luck” (Sabin 2015). Similarly, people also should not wash their hair during the first two days of the new year.

14 * The color red is the central color of Spring Festival: red is believed to bring good luck and scare away evil spirits. Red is a dominant color in clothing and paper decoration during the festivities (Smith 2000).

15 * During the festivities, there are many traditional snacks and dishes. Sticky cakes and dumplings are commonly eaten throughout these days. If you’re lucky, you might find a coin in your dumpling.

16 * Besides all kinds of delicacies, long noodles are also often eaten during Chinese New Year as they represent longevity.

“Preparing for New Year dinner with the family,” says one Weibo user, posting this picture.

“Preparing for New Year dinner with the family,” says one Weibo user, posting this picture.

17 * Mao Zedong was praised for celebrating Chinese New Year together with the common people (see image).

18 * In 1986,high-ranking official Hu Yaobang celebrated Chinese New Year in the southern province of Yunnan. In the featured image, Hu Yaobang dances traditional ethnic dance together with locals (360doc).

19 * The year-end bonus (年终奖金) is an important issue during Chinese New Year. Some employees receive large amounts of money from their companies, others are disappointed with what they get.

20 * Most text messages are sent during Chinese New Year. The current record stands at 19 billion.

21 * If you mention ‘Chinese New Year’ on Weixin, small moneybags fall drop down in the screen.

22 * The best-watched television show during New Year’s is the Spring Festival Eve television gala by CCTV. With an estimated 800 million viewers, this show has the largest audience for any entertainment show in the world, surpassing the Super Bowl.

23 * The first Spring Festival Eve television gala took place in 1983. The show consists of different acts, including comedy sketches (Bin 1998, 220).

24 * This year, Weibo users can watch the live broadcasting of the television gala while commenting and interacting with other Weibo users without switching screens.

25 * Before New Year’s, Hong Kong hospitals filled up with expecting mothers waiting for a caesarean section in order to make sure their babies were still born in the Year of the Horse, as it is considered a good year to have children.

26 * It is tradition to burn paper money or ‘ghost money’ during the festivities as offerings to the spirits and deceased. The paper money is sometimes made from rice paper, but silver or gold metallic paper is also common.

27 * Doctors have warned people to wear face masks when burning metallic money, as the substances that are produced when burning this money are a potential health risk.

28 * For many young single men and women, Chinese New Year is the period when they receive the most pressure from their parents to get married. Over recent years, a trend has come up where single women rent a date to take home to their parents in order to avoid critical questions on their single status.

29 * The pressure to get married is especially difficult for Chinese gays who have not come out. A Chinese gay rights organisation has therefore launched a video titled ‘Coming Home‘, urging gays to talk to their families and telling parents to be supportive during Spring Festival.

30 * A new year means a new calendar. Giving a calendar is tradition during Chinese New Year.

31 * This year, the government is giving away “anti-extremism” calendars in Urumqi in the northwestern region of Xinjiang, home to China’s Muslim Uighur population (also read: Islam in China).

32 * You might see a lot of people eating oranges and pomelo’s during New Year. The Chinese words for oranges and tangerines (橘, 桔: ju) sound like ‘luck’ (吉, ji), while pomelo (柚, you) sounds like ‘to have’ (有 you). Eating pomelo’s and oranges is thus considered to bring good luck.

33 * The Year of the Goat has a ‘mascot’ this year. Yangyang the Goat was revealed on the Weibo account of CCTV’s Spring Festival television gala. It is the first time the Spring Festival gala has a mascot.

34 * Chinese New Year was officially cancelled in 1967 at the time of the Cultural Revolution, as it was believed that the festivities would distract the people from their “revolutionary duties”.

35 * Besides all the do’s, there are also specific don’ts during Spring Festival: do not give clocks as presents, because they symbolise time running out, avoid the use of sharp objects, as they might cut off good fortune, and do not wear black or tell ghost stories, as it might bring about negative energy (John 2015).

– by Manya Koetse

[button link=”http://www.twitter.com/whatsonweibo” type=”icon” icon=”heart” newwindow=”yes”] Follow us on Twitter[/button]

References

Bin, Zhao. 1998. “Popular Family Television and Party Ideology: The Spring Festival Eve Happy Gathering.” Journal of Composite Materials 33: 928–40.

Chey, Ong Siew. 2011. China Condensed: 5,000 Years of History & Culture. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd.

John, Simi. 2015. “Chinese New Year 2015: Top ten superstitions.” International Business Times, February 17 http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/chinese-new-year-2015-top-ten-superstitions-1488173 [18.02.15].

Sabin, Lamiat. 2015. “Chinese New Year 2015: When is it, how is it celebrated – and what does the Goat signify?” The Independent, Feb 17 http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/chinese-new-year-2015-when-is-it-how-is-it-celebrated–and-what-does-the-goat-signify-10049702.html [17.02.15].

Smith, Christine. 2000. Chinese New Year Activities. Teacher Created Resources. https://books.google.com/books?id=whFBVSNN_ZkC&pgis=1.

Somerville, Neil. 2014. The Goat in 2015: Your Chinese Horoscope. HarperCollins Publishers. https://books.google.com/books?id=lrzpAgAAQBAJ&pgis=1.

Xing, Li. 2006. Festivals of China’s Ethnic Minorities. China Intercontinental Press 中信出版社.

©2015 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy.

Published

1 day agoon

May 3, 2024

It seemed like such a good idea. For this year’s World Book Day, Chinese tea brand LELECHA (乐乐茶) put a spotlight on Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881-1936), one of the most celebrated Chinese authors the 20th century and turned him into the the ‘brand ambassador’ of their special new “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙) milk tea.

LELECHA is a Chinese chain specializing in new-style tea beverages, including bubble tea and fruit tea. It debuted in Shanghai in 2016, and since then, it has expanded rapidly, opening dozens of new stores not only in Shanghai but also in other major cities across China.

Starting on April 23, not only did the LELECHA ‘Smoky Oolong” paper cups feature Lu Xun’s portrait, but also other promotional materials by LELECHA, such as menus and paper bags, accompanied by the slogan: “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” (“老烟腔,新青年”). The marketing campaign was a joint collaboration between LELECHA and publishing house Yilin Press.

Lu Xun featured on LELECHA products, image via Netease.

The slogan “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” is a play on the Chinese magazine ‘New Youth’ or ‘La Jeunesse’ (新青年), the influential literary magazine in which Lu’s famous short story, “Diary of a Madman,” was published in 1918.

The design of the tea featuring Lu Xun’s image, its colors, and painting style also pay homage to the era in which Lu Xun rose to prominence.

Lu Xun (pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a leading figure within China’s May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1915-24) is also referred to as the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance. It was the cultural revolution brought about by the political demonstrations on the fourth of May 1919 when citizens and students in Beijing paraded the streets to protest decisions made at the post-World War I Versailles Conference and called for the destruction of traditional culture[1].

In this historical context, Lu Xun emerged as a significant cultural figure, renowned for his critical and enlightened perspectives on Chinese society.

To this day, Lu Xun remains a highly respected figure. In the post-Mao era, some critics felt that Lu Xun was actually revered a bit too much, and called for efforts to ‘demystify’ him. In 1979, for example, writer Mao Dun called for a halt to the movement to turn Lu Xun into “a god-like figure”[2].

Perhaps LELECHA’s marketing team figured they could not go wrong by creating a milk tea product around China’s beloved Lu Xun. But for various reasons, the marketing campaign backfired, landing LELECHA in hot water. The topic went trending on Chinese social media, where many criticized the tea company.

Commodification of ‘Marxist’ Lu Xun

The first issue with LELECHA’s Lu Xun campaign is a legal one. It seems the tea chain used Lu Xun’s portrait without permission. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s great-grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation, quickly demanded an end to the unauthorized use of Lu Xun’s image on tea cups and other merchandise. He even hired a law firm to take legal action against the campaign.

Others noted that the image of Lu Xun that was used by LELECHA resembled a famous painting of Lu Xun by Yang Zhiguang (杨之光), potentially also infringing on Yang’s copyright.

But there are more reasons why people online are upset about the Lu Xun x LELECHA marketing campaign. One is how the use of the word “smoky” is seen as disrespectful towards Lu Xun. Lu Xun was known for his heavy smoking, which ultimately contributed to his early death.

It’s also ironic that Lu Xun, widely seen as a Marxist, is being used as a ‘brand ambassador’ for a commercial tea brand. This exploits Lu Xun’s image for profit, turning his legacy into a commodity with the ‘smoky oolong’ tea and related merchandise.

“Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you in an article. ”

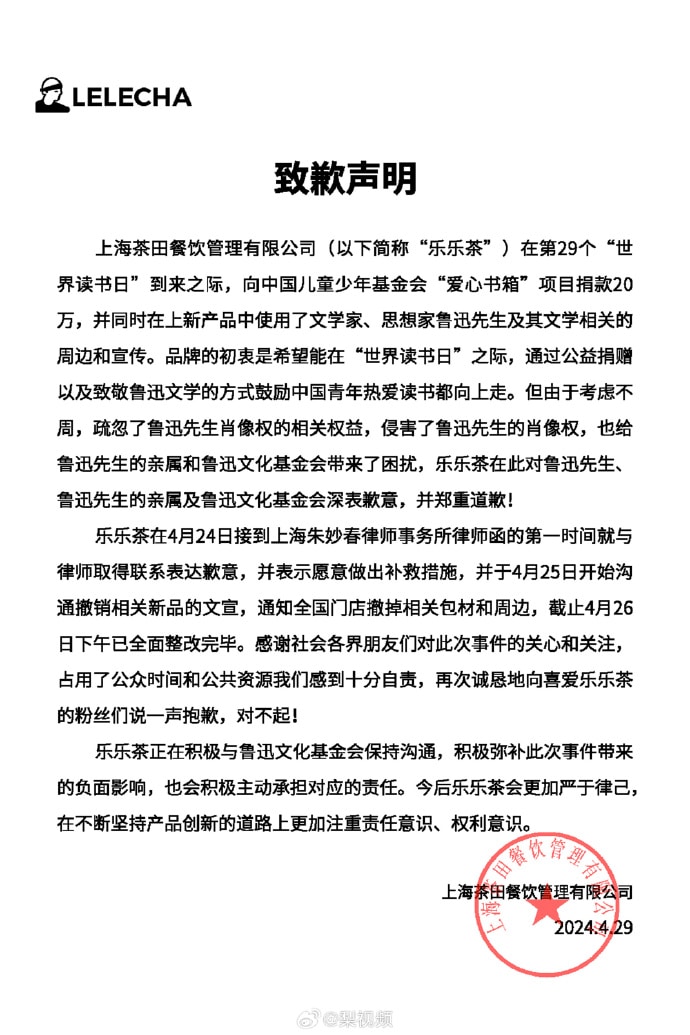

On April 29, LELECHA finally issued an apology to Lu Xun’s relatives and the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation for neglecting the legal aspects of their marketing campaign. They claimed it was meant to promote reading among China’s youth. All Lu Xun materials have now been removed from LELECHA’s stores.

Statement by LELECHA.

On Chinese social media, where the hot tea became a hot potato, opinions on the issue are divided. While many netizens think it is unacceptable to infringe on Lu Xun’s portrait rights like that, there are others who appreciate the merchandise.

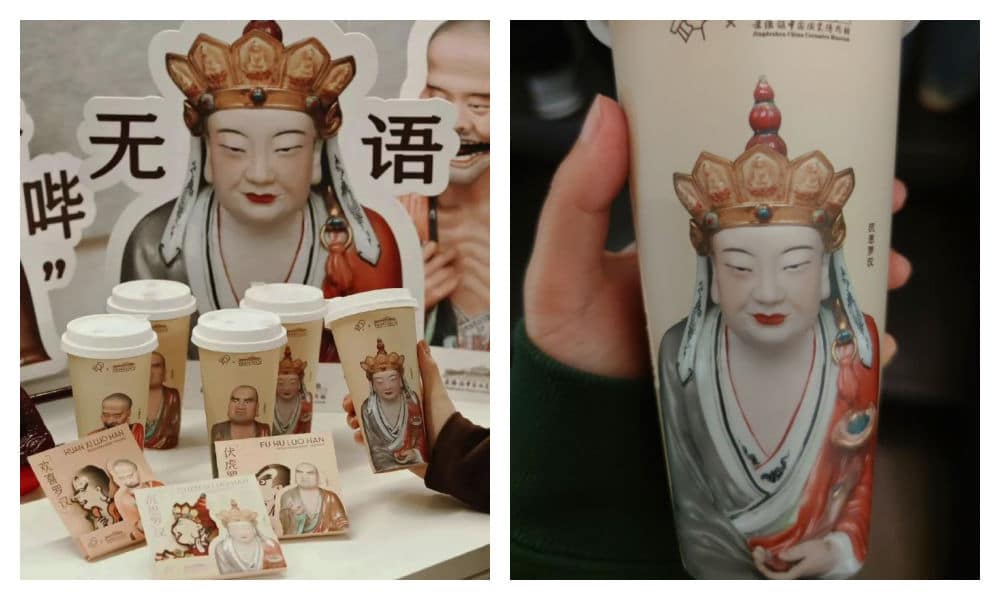

The LELECHA controversy is similar to another issue that went trending in late 2023, when the well-known Chinese tea chain HeyTea (喜茶) collaborated with the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum to release a special ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ (佛喜) latte tea series adorned with Buddha images on the cups, along with other merchandise such as stickers and magnets. The series featured three customized “Buddha’s Happiness” cups modeled on the “Speechless Bodhisattva” (无语菩萨), which soon became popular among netizens.

The HeyTea Buddha latte series, including merchandise, was pulled from shelves just three days after its launch.

However, the ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ success came to an abrupt halt when the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Shenzhen intervened, citing regulations that prohibit commercial promotion of religion. HeyTea wasted no time challenging the objections made by the Bureau and promptly removed the tea series and all related merchandise from its stores, just three days after its initial launch.

Following the Happy Buddha and Lu Xun milk tea controversies, Chinese tea brands are bound to be more careful in the future when it comes to their collaborative marketing campaigns and whether or not they’re crossing any boundaries.

Some people couldn’t care less if they don’t launch another campaign at all. One Weibo user wrote: “Every day there’s a new collaboration here, another one there, but I’d just prefer a simple cup of tea.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Schoppa, Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia UP, 159.

[2]Zhong, Xueping. 2010. “Who Is Afraid Of Lu Xun? The Politics Of ‘Debates About Lu Xun’ (鲁迅论争lu Xun Lun Zheng) And The Question Of His Legacy In Post-Revolution China.” In Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China, 257–284, 262.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Zibo had its BBQ moment. Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine with its special take on malatang. Tourism marketing in China will never be the same again.

Published

1 month agoon

April 1, 2024

Since the early post-pandemic days, Chinese cities have stepped up their game to attract more tourists. The dynamics of Chinese social media make it possible for smaller, lesser-known destinations to gain overnight fame as a ‘celebrity city.’ Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine.

During this Qingming Festival holiday, there is one Chinese city that will definitely welcome more visitors than usual. Tianshui, the second largest city in Gansu Province, has emerged as the latest travel hotspot among domestic tourists following its recent surge in popularity online.

Situated approximately halfway along the Lanzhou-Xi’an rail line, this ancient city wasn’t previously a top destination for tourists. Most travelers would typically pass through the industrial city to see the Maiji Shan Grottoes, the fourth largest Buddhist cave complex in China, renowned for its famous rock carvings along the Silk Road.

But now, there is another reason to visit Tianshui: malatang.

Gansu-Style Malatang

Málàtàng (麻辣烫), which literally means ‘numb spicy hot,’ is a popular Chinese street food dish featuring a diverse array of ingredients cooked in a soup base infused with Sichuan pepper and dried chili pepper. There are multiple ways to enjoy malatang.

When dining at smaller street stalls, it’s common to find a selection of skewered foods—ranging from meats to quail eggs and vegetables—simmering in a large vat of flavorful spicy broth. This communal dining experience is affordable and convenient for solo diners or smaller groups seeking a hotpot-style meal.

In malatang restaurants, patrons can usually choose from a selection of self-serve skewered ingredients. You have them weighed, pay, and then have it prepared and served in a bowl with a preferred soup base, often with the option to choose the level of spiciness, from super hot to mild.

Although malatang originated in Sichuan, it is now common all over China. What makes Tianshui malatang stand out is its “Gansu-style” take, with a special focus on hand-pulled noodles, potato, and spicy oil.

An important ingredient for the soup base is the somewhat sweet and fragrant Gangu chili, produced in Tianshui’s Gangu County, known as “the hometown of peppers.”

Another ingredient is Maiji peppercorns (used in the sauce), and there are more locally produced ingredients, such as the black fungi from Qingshui County.

One restaurant that made Tianshui’s malatang particularly famous is Haiying Malatang (海英麻辣烫) in the city’s Qinzhou District. On February 13, the tiny restaurant, which has been around for three decades, welcomed an online influencer (@一杯梁白开) who posted about her visit.

The vlogger was so enthusiastic about her taste of “Gansu-style malatang,” that she urged her followers to try it out. It was the start of something much bigger than she could have imagined.

Replicating Zibo

Tianshui isn’t the first city to capture the spotlight on Chinese social media. Cities such as Zibo and Harbin have previously surged in popularity, becoming overnight sensations on platforms like Weibo, Xiaohongshu, and Douyin.

This phenomenon of Chinese cities transforming into hot travel destinations due to social media frenzy became particularly noteworthy in early 2023.

During the Covid years, various factors sparked a friendly competition among Chinese cities, each competing to attract the most visitors and to promote their city in the best way possible.

The Covid pandemic had diverse impacts on the Chinese domestic tourism industry. On one hand, domestic tourism flourished due to the pandemic, as Chinese travelers opted for destinations closer to home amid travel restrictions. On the other hand, the zero-Covid policy, with its lockdowns and the absence of foreign visitors, posed significant challenges to the tourism sector.

Following the abolition of the zero-Covid policy, tourism and marketing departments across China swung into action to revitalize their local economy. China’s social media platforms became battlegrounds to capture the attention of Chinese netizens. Local government officials dressed up in traditional outfits and created original videos to convince tourists to visit their hometowns.

Zibo was the first city to become an absolute social media sensation in the post-Covid era. The old industrial and mining city was not exactly known as a trendy tourist destination, but saw its hotel bookings going up 800% in 2023 compared to pre-Covid year 2019. Among others factors contributing to its success, the city’s online marketing campaign and how it turned its local BBQ culture into a unique selling point were both critical.

Zibo crowds, image via 163.com.

Since 2023, multiple cities have tried to replicate the success of Zibo. Although not all have achieved similar results, Harbin has done very well by becoming a meme-worthy tourist attraction earlier in 2024, emphasizing its snow spectacle and friendly local culture.

By promoting its distinctive take on malatang, Tianshui has emerged as the next city to captivate online audiences, leading to a surge in visitor numbers.

Like with Zibo and Harbin, one particular important strategy used by these tourist offices is to swiftly respond to content created by travel bloggers or food vloggers about their cities, boosting the online attention and immediately seizing the opportunity to turn online success into offline visits.

A Timeline

What does it take to become a Chinese ‘celebrity city’? Since late February and early March of this year, various Douyin accounts started posting about Tianshui and its malatang.

They initially were the main reason driving tourists to the city to try out malatang, but they were not the only reason – city marketing and state media coverage also played a role in how the success of Tianshui played out.

Here’s a timeline of how its (online) frenzy unfolded:

- July 25, 2023: First video on Douyin about Tianshui’s malatang, after which 45 more videos by various accounts followed in the following six months.

- Feb 5, 2024: Douyin account ‘Chuanshuo Zhong de Bozi’ (传说中的波仔) posts a video about malatang streetfood in Gansu

- Feb 13, 2024: Douyin account ‘Yibei Liangbaikai’ (一杯梁白开) posts a video suggesting the “nationwide popularization of Gansu-style malatang.” This video is an important breakthrough moment in the success of Tianshui as a malatang city.

- Feb – March ~, 2024: The Tianshui Culture & Tourism Bureau is visiting sites, conducting research, and organizing meetings with different departments to establish the “Tianshui city + malatang” brand (文旅+天水麻辣烫”品牌) as the city’s new “business card.”

- March 11, 2024: Tianshui city launches a dedicated ‘spicy and hot’ bus line to cater to visitors who want to quickly reach the city’s renowned malatang spots.

- March 13-14, 2024: China’s Baidu search engine witnesses exponential growth in online searches for Tianshui malatang.

- March 14-15, 2024: The boss of Tianshui’s popular Haiying restaurant goes viral after videos show him overwhelmed and worried he can’t keep up. His facial expression becomes a meme, with netizens dubbing it the “can’t keep up-expression” (“烫不完表情”).

The worried and stressed expression of this malatang diner boss went viral overnight.

- March 17, 2024: Chinese media report about free ‘Tianshui malatang’ wifi being offered to visitors as a special service while they’re standing in line at malatang restaurants.

- March 18, 2024: Tianshui opens its first ‘Malatang Street’ where about 40 stalls sell malatang.

- March 18, 2024: Chinese local media report that one Tianshui hair salon (Tony) has changed its shop into a malatang shop overnight, showing just how big the hype has become.

- March 21, 2024: A dedicated ‘Tianshui malatang’ train started riding from Lanzhou West Station to Tianshui (#天水麻辣烫专列开行#).

- March 21, 2024: Chinese actor Jia Nailiang (贾乃亮) makes a video about having Tianshui malatang, further adding to its online success.

- March 30, 2024: A rare occurrence: as the main attraction near Tianshui, the Maiji Mountain Scenic Area announces that they’ve reached the maximum number of visitors and don’t have the capacity to welcome any more visitors, suspending all ticket sales for the day.

- April 1, 2024: Chinese presenter Zhang Dada was spotted making malatang in a local Tianshui restaurant, drawing in even more crowds.

A New Moment to Shine

Fame attracts criticism, and that also holds true for China’s ‘celebrity cities.’

Some argue that Tianshui’s malatang is overrated, considering the richness of Gansu cuisine, which offers much more than just malatang alone.

When Zibo reached hype status, it also faced scrutiny, with some commenters suggesting that the popularity of Zibo BBQ was a symptom of a society that’s all about consumerism and “empty social spectacle.”

There is a lot to say about the downsides of suddenly becoming a ‘celebrity city’ and the superficiality and fleetingness that comes with these kinds of trends. But for many locals, it is seen as an important moment as they see their businesses and cities thrive.

Even after the hype fades, local businesses can maintain their success by branding themselves as previously viral restaurants. When I visited Zibo a few months after its initial buzz, many once-popular spots marketed themselves as ‘wanghong’ (网红) or viral celebrity restaurants.

For the city itself, being in the spotlight holds its own value in the long run. Even after the hype has peaked and subsided, the gained national recognition ensures that these “trendy” places will continue to attract visitors in the future.

According to data from Ctrip, Tianshui experienced a 40% increase in tourism spending since March (specifically from March 1st to March 16th). State media reports claim that the city saw 2.3 million visitors in the first three weeks of March, with total tourism revenue reaching nearly 1.4 billion yuan ($193.7 million).

There are more ripple effects of Tianshui’s success: Maiji Shan Grottoes are witnessing a surge in visitors, and local e-commerce companies are experiencing a spike in orders from outside the city. Even when they’re not in Tianshui, people still want a piece of Tianshui.

By now, it’s clear that tourism marketing in China will never be the same again. Zibo, Harbin, and Tianshui exemplify a new era of destination hype, requiring a unique selling point, social media success, strong city marketing, and a friendly and fair business culture at the grassroots level.

While Zibo’s success was largely organic, Harbin’s was more orchestrated, and Tianshui learned from both. Now, other potential ‘celebrity’ cities are preparing to go viral, learning from the successes and failures of their predecessors to shine when their time comes.

By Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

The Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight2 months ago

China Insight2 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

-

China Arts & Entertainment2 weeks ago

China Arts & Entertainment2 weeks ago“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

-

China Media2 months ago

China Media2 months agoParty Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”