China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Editorial: Behind SK-II’s China’s “Change Destiny” Campaign

Some call the recent ad campaign of skincare brand SK-II hypocritical. Is it?

Published

8 years agoon

The ad campaign of skin care brand SK-II has been all over the news, both in and outside China, since it was launched on April 7 – triggering much discussion on the phenomenon of China’s ‘leftover women’ and the ad itself, with some calling it ‘hypocritical’. But is it?

Japanese skin care brand SK-II has caused quite a stir in China with its latest ad campaign that focuses on unmarried women over the age of 25 in China, who have been labeled ‘leftover women’ by Chinese media for years. The video, that is part of the brand’s worldwide ‘Change Destiny’ campaign, has been watched over 10 million times within ten days of its release.

“A wrinkled past in China”

It’s not the first time SK-II has caused commotion in China, where the brand has a somewhat of a wrinkled past. In 2005, the company was suspected of deceiving consumers with its anti-wrinkle products, according to Chinese state media. Even before this news, Chinese netizens were already calling for a boycott of the Japanese SK-II in 2004.

In 2006, SK-II producer Procter & Gamble (宝洁) stopped the import of all SK-II products in China after the use of banned substances was detected by Chinese inspectors, followed by much controversy and media attention. According to an 2006 Ad Age article, the manufacturer defended the chemicals in SK-II as the same traces were found in other comparable products by companies such as Lancome or Estee Lauder – yet they suffered no consequences in their China sales. This left some industry observers wondering whether or not the brand was purposely picked on by the Chinese government for its Japanese origin, linking it to anti-Japanese sentiment that has existed in China since World War II.

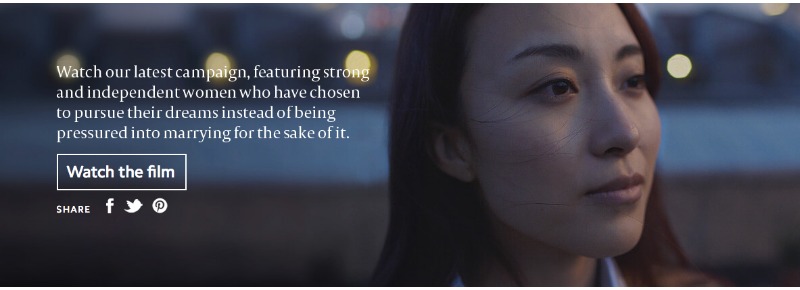

A decade later, SK-II has launched its major ‘Change Destiny’ (#改写命运#) brand campaign that features, according to the brand: “(..) strong and independent women who have chosen to pursue their dreams instead of being pressured into marrying for the sake of it” (SK-II website).

SK-II ‘change destiny’ campaign. See the video here.

SK-II ‘change destiny’ campaign. See the video here.

“I won’t be happy if I marry for the sake of marrying”

The company chose the successful Swedish ad company Fordman & Bodenfors to produce their campaign video. This ad agency also produced the video for H&M’s world recycle week featuring MIA, that received nearly a million views on Youtube within a week after its release.

The SK-II 4-minute-video titled ‘Marriage Market Takeover‘ features several unmarried Chinese women who talk about the pressure they experience from their family and society at large to get married, and the stigmatization they face for being single.

(1) “You are a leftover woman”, (2) “You become a subject people talk about”, (3) “And you get so much social pressure”.

After talking about their current situation, the women go to a so-called ‘marriage market’ – a well-known event in China that is generally held on Sundays in urban parks. This is a place where parents stand with ‘ads’ that tell the age, profession, income, and other details about their son or daughter, in the hopes of finding a suitable match for them.

Shot of the ‘marriage market’ in th Shanghai Park in the video.

Shot of the ‘marriage market’ in th Shanghai Park in the video.

Instead of coming to the market in search of a partner, they come there to see their own ‘ad’. The park in Shanghai where the ‘marriage market’ is normally held now has a wall of ads that are likely placed there for the SK-II campaign film. These ‘ads’ show the portraits of the different women, with an accompanying text saying things like: “I won’t be happy if I marry for the sake of marrying”.

Their parents then arrive at the market and see their daughter’s picture and read her message to them. They are seemingly moved, and then express their understanding for their daughter’s situation.

“There is a word for advertising like this, and that word is ‘hypocrisy’.”

The SK-II campaign video proved to be a huge success – it had already hit 1.2 million views on Youku within the first day of launching. The reactions on Chinese social media were overall very positive, as mainly female netizens recognized their own experiences in the video. Some exemplary netizens’ reactions were: “Whether I’m married or not is nobody’s business,” or: “I won’t stop pursuing my dreams because of pressure from society,” and: “Marriage is about feeling, not about age.”

But the ad also had critics. Although women’s rights activist Zheng Churan generally welcomed the ad despite its commercial motives, she did criticize how it focused on the stereotype of the “leftover woman”, ignoring “the struggles of poor, less-educated women”. As she said: “We only see white-collar, elite women in this ad, but an 18-year-old factory girl pressed into marriage still has no voice” (Japan Times).

State media outlet Xinhua news quoted online female writer Gu Yingying saying that the ad “splashes a bottle of dirty water onto (women’s) independence and confidence”, and that it was “full of sentiments of depression and messages about society’s intolerance and conservatism”.

China’s state broadcaster CCTV reported on the video being “welcomed across China”, but also called it an ad for “pro-singledom”.

Outside the China media sphere, Quartz writer Annalisa Merelli responded to the campaign with an article titled “Another viral ad tries to “empower” women while selling them products to look young forever“. In this article, Merelli writes: “There is a word for advertising like this, and that word is “hypocrisy”. To this, she adds:

“No matter the amount of moving music and public displays of support, there is simply no way a beauty brand should be able to both profit from a growing huge market ($191.7 billion projected globally for anti-aging alone) that feeds off the idea that you look too dark-skinned and too old, and also play fairy godmother of female empowerment” (Quartz, April 12).

“The exclusion of the ’18-year-old factory girl’ is understandable: she is not SK-II’s target audience.”

But how ‘hypocritical’ is this ad for addressing China’s ‘leftover women’ phenomenon while having commercial interests? First, the brand does not hide the video’s commercial aspect. On the contrary, the SK-II brand logo is clearly marked in the ad and the video was released from official SK-II channels. Second, the women represented in the video are the brand’s intended consumers. Within China, it’s mostly the highly educated and urban women who buy SK-II kinds of brands and suffer pressure from society for being unmarried- in that way, there simply and very apparently is a way that a beauty brand can profit from a huge market while encouraging their “female empowerment”.

The exclusion of the ’18-year-old factory girl’ is understandable from a commercial perspective: she is not SK-II’s target audience. An SK-II moisturizer currently is priced around 1370 RMB (±211 US$) on Tmall. According to China Labour Bulletin, the minimum wages in China vary across China, from 850 RMB per month (131 US$ )to 2030 RMB (313 US$). SK-II products simply are an unattainable luxury for many women in China, except for those women who generally have a solid educational background, a blossoming career, and the access to high-end stores that sell SK-II – which are often the same women facing the ‘leftover’ pressure.

Commercial motives aside, the pressure China’s unmarried women suffer is real. About 80% of China’s bachelorettes over the age of 24 experience pressure by their families to get married, whilst a Zhenai survey pointed out that 50% of Chinese men think women are already ‘leftover’ when they are unmarried by the age of 25.

The pressure, being both familial and societal, comes from all angles. Parents, coming from a completely different generation, often lack the understanding that their daughter is waiting for ‘the one’. As the dad in the video says: “In our days, matchmaking was simple: you got matched, you got married.” They then suffer extra pressure because those born after 1978 were children of China’s one-child policy, which means they are often their parents’ only child able to give them a grandchild.

In society at large, the pressure is also double-faced. Besides deeply-rooted Confucian ideas about respecting one’s parents by getting married and fulfilling one’s role as “good wife and wise mother”, there is also an existing unbalance in male/female ratio. With millions of men left without an eligible partner and an aging China, there is ample societal need for single women to settle down and get married – which makes being ‘leftover’ all the more difficult. The fact that there are Chinese writers and academics calling on women to set some of their personal happiness aside to get married “for the country and for society” does not make things easier.

“By choosing the ‘leftover’ issue and turning it into a positive message, SK-II has rebranded itself in the PRC as a progressive and empowering brand name.”

SK-II was not hypocritical in being a commercial company releasing an empowering message, nor is the pressure on women it pictures unrealistic. The parents’ swift transformation after seeing their daughter’s ad, however, could be said to be somewhat starry-eyed; their sudden understanding for their daughter’s situation is unlikely to change traditional perceptions on China’s unmarried women overnight. This does not make SK-II hypocritical; it just makes the video the commercial that it is. Luxury brands are supposed to give consumers a mental connection to positivity, confidence, and bright possibilities; not leave us pessimistic about the future.

The brand’s choice for the topic of ‘leftover women’ is a strategic one. SK-II had to make up for some of its wrinkled past in China. The consumers it mainly needs to win over are also the women who often face pressure in everyday China. By choosing the ‘leftover’ issue and turning it into a positive message, SK-II has rebranded itself in the PRC as a progressive and empowering brand name. It also profits from one of the world’s most important markets by doing so. Through this video, SK-II has won the sympathy of an audience of millions who have cash to spend on the luxury items SK-II promotes.

An additional reason why SK-II’s campaign focus is a smart strategic move, is that the phenomenon of ‘leftover women’ is also a popular recurring topic internationally; the struggles of single Chinese women have captured the interest of the mainstream Western media for some years now. The ad campaign therefore went viral both in and outside – killing two birds in one stone.

All in all, Forsman & Bodenfors have done a great job at what they do: SK-II’s brand name is all over the web, the majority of Chinese netizens welcomed the ‘change destiny’ message with open arms, and they have reiterated what the product behind the campaign is all about. After all, who doesn’t want a pressure-free life, a wrinkle-free face, and a happy end to a troubled story?

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy.

Published

8 hours agoon

May 3, 2024

It seemed like such a good idea. For this year’s World Book Day, Chinese tea brand LELECHA (乐乐茶) put a spotlight on Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881-1936), one of the most celebrated Chinese authors the 20th century and turned him into the the ‘brand ambassador’ of their special new “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙) milk tea.

LELECHA is a Chinese chain specializing in new-style tea beverages, including bubble tea and fruit tea. It debuted in Shanghai in 2016, and since then, it has expanded rapidly, opening dozens of new stores not only in Shanghai but also in other major cities across China.

Starting on April 23, not only did the LELECHA ‘Smoky Oolong” paper cups feature Lu Xun’s portrait, but also other promotional materials by LELECHA, such as menus and paper bags, accompanied by the slogan: “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” (“老烟腔,新青年”). The marketing campaign was a joint collaboration between LELECHA and publishing house Yilin Press.

Lu Xun featured on LELECHA products, image via Netease.

The slogan “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” is a play on the Chinese magazine ‘New Youth’ or ‘La Jeunesse’ (新青年), the influential literary magazine in which Lu’s famous short story, “Diary of a Madman,” was published in 1918.

The design of the tea featuring Lu Xun’s image, its colors, and painting style also pay homage to the era in which Lu Xun rose to prominence.

Lu Xun (pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a leading figure within China’s May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1915-24) is also referred to as the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance. It was the cultural revolution brought about by the political demonstrations on the fourth of May 1919 when citizens and students in Beijing paraded the streets to protest decisions made at the post-World War I Versailles Conference and called for the destruction of traditional culture[1].

In this historical context, Lu Xun emerged as a significant cultural figure, renowned for his critical and enlightened perspectives on Chinese society.

To this day, Lu Xun remains a highly respected figure. In the post-Mao era, some critics felt that Lu Xun was actually revered a bit too much, and called for efforts to ‘demystify’ him. In 1979, for example, writer Mao Dun called for a halt to the movement to turn Lu Xun into “a god-like figure”[2].

Perhaps LELECHA’s marketing team figured they could not go wrong by creating a milk tea product around China’s beloved Lu Xun. But for various reasons, the marketing campaign backfired, landing LELECHA in hot water. The topic went trending on Chinese social media, where many criticized the tea company.

Commodification of ‘Marxist’ Lu Xun

The first issue with LELECHA’s Lu Xun campaign is a legal one. It seems the tea chain used Lu Xun’s portrait without permission. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s great-grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation, quickly demanded an end to the unauthorized use of Lu Xun’s image on tea cups and other merchandise. He even hired a law firm to take legal action against the campaign.

Others noted that the image of Lu Xun that was used by LELECHA resembled a famous painting of Lu Xun by Yang Zhiguang (杨之光), potentially also infringing on Yang’s copyright.

But there are more reasons why people online are upset about the Lu Xun x LELECHA marketing campaign. One is how the use of the word “smoky” is seen as disrespectful towards Lu Xun. Lu Xun was known for his heavy smoking, which ultimately contributed to his early death.

It’s also ironic that Lu Xun, widely seen as a Marxist, is being used as a ‘brand ambassador’ for a commercial tea brand. This exploits Lu Xun’s image for profit, turning his legacy into a commodity with the ‘smoky oolong’ tea and related merchandise.

“Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you in an article. ”

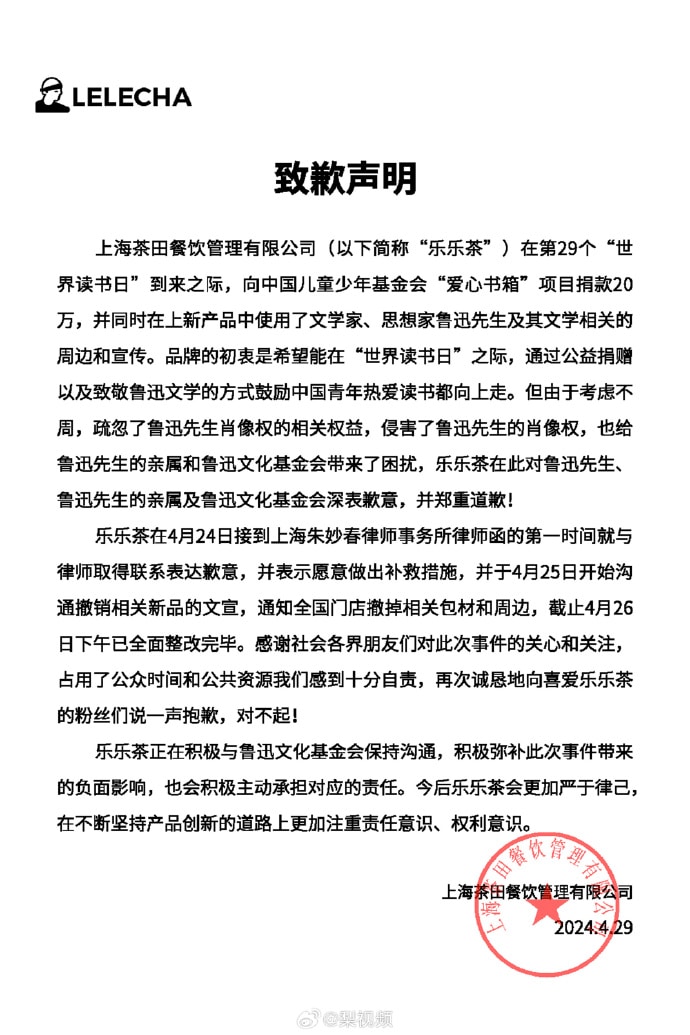

On April 29, LELECHA finally issued an apology to Lu Xun’s relatives and the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation for neglecting the legal aspects of their marketing campaign. They claimed it was meant to promote reading among China’s youth. All Lu Xun materials have now been removed from LELECHA’s stores.

Statement by LELECHA.

On Chinese social media, where the hot tea became a hot potato, opinions on the issue are divided. While many netizens think it is unacceptable to infringe on Lu Xun’s portrait rights like that, there are others who appreciate the merchandise.

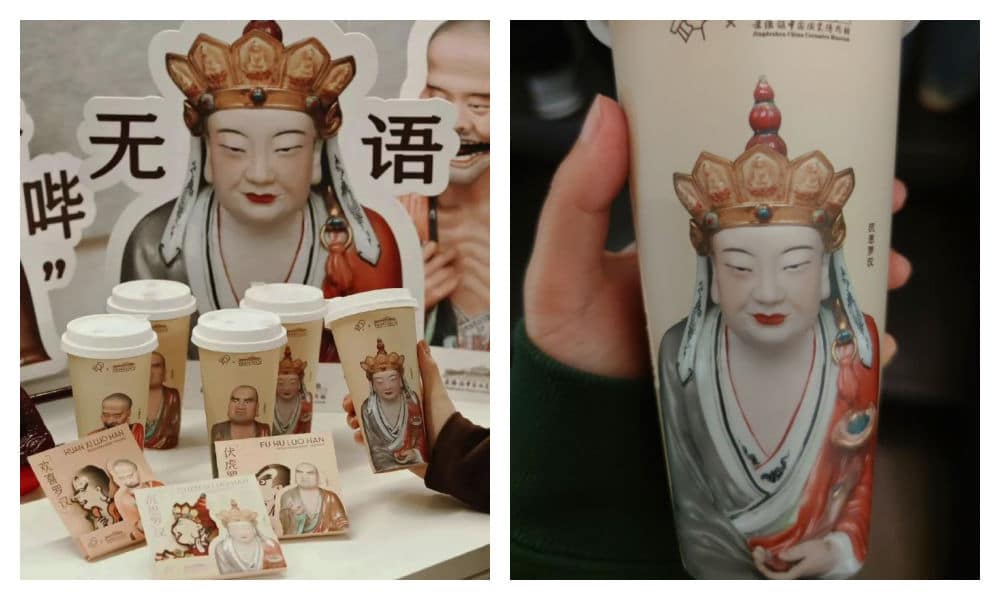

The LELECHA controversy is similar to another issue that went trending in late 2023, when the well-known Chinese tea chain HeyTea (喜茶) collaborated with the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum to release a special ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ (佛喜) latte tea series adorned with Buddha images on the cups, along with other merchandise such as stickers and magnets. The series featured three customized “Buddha’s Happiness” cups modeled on the “Speechless Bodhisattva” (无语菩萨), which soon became popular among netizens.

The HeyTea Buddha latte series, including merchandise, was pulled from shelves just three days after its launch.

However, the ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ success came to an abrupt halt when the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Shenzhen intervened, citing regulations that prohibit commercial promotion of religion. HeyTea wasted no time challenging the objections made by the Bureau and promptly removed the tea series and all related merchandise from its stores, just three days after its initial launch.

Following the Happy Buddha and Lu Xun milk tea controversies, Chinese tea brands are bound to be more careful in the future when it comes to their collaborative marketing campaigns and whether or not they’re crossing any boundaries.

Some people couldn’t care less if they don’t launch another campaign at all. One Weibo user wrote: “Every day there’s a new collaboration here, another one there, but I’d just prefer a simple cup of tea.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Schoppa, Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia UP, 159.

[2]Zhong, Xueping. 2010. “Who Is Afraid Of Lu Xun? The Politics Of ‘Debates About Lu Xun’ (鲁迅论争lu Xun Lun Zheng) And The Question Of His Legacy In Post-Revolution China.” In Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China, 257–284, 262.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Who’s gonna buy this Zara dress in China? “I’m afraid that someone will say I stole the apron from Haidilao.”

Published

2 weeks agoon

April 19, 2024

A short dress sold by Zara has gone viral in China for looking like the aprons used by the popular Chinese hotpot chain Haidilao.

“I really thought it was a Zara x Haidialo collab,” some customers commented. Others also agree that the first thing they thought about when seeing the Zara dress was the Haidilao apron.

The “original” vs the Zara dress.

The dress has become a popular topic on Xiaohongshu and other social media, where some images show the dress with the Haidilao logo photoshopped on it to emphasize the similarity.

One post on Xiaohongshu discussing the dress, with the caption “Curious about the inspiration behind Zara’s design,” garnered over 28,000 replies.

Haidilao, with its numerous restaurants across China, is renowned for its hospitality and exceptional customer service. Anyone who has ever dined at their restaurants is familiar with the Haidilao apron provided to diners for protecting their clothes from food or oil stains while enjoying hotpot.

These aprons are meant for use during the meal and should be returned to the staff afterward, rather than taken home.

The Haidilao apron.

However, many people who have dined at Haidilao may have encountered the following scenario: after indulging in drinks and hotpot, they realize they are still wearing a Haidilao apron upon leaving the restaurant. Consequently, many hotpot enthusiasts may have an ‘accidental’ Haidilao apron tucked away at home somewhere.

This only adds to the humor of the latest Zara dress looking like the apron. The similarity between the Zara dress and the Haidilao apron is actually so striking, that some people are afraid to be accused of being a thief if they would wear it.

One Weibo commenter wrote: “The most confusing item of this season from Zara has come out. It’s like a Zara x Haidilao collaboration apron… This… I can’t wear it: I’m afraid that someone will say I stole the apron from Haidilao.”

Funnily enough, the Haidilao apron similarity seems to have set off a trend of girls trying on the Zara dress and posting photos of themselves wearing it.

It’s doubtful that they’re actually purchasing the dress. Although some commenters say the dress is not bad, most people associate it too closely with the Haidilao brand: it just makes them hungry for hotpot.

By Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

The Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight2 months ago

China Insight2 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

-

China Media2 months ago

China Media2 months agoParty Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

-

China Arts & Entertainment2 weeks ago

China Arts & Entertainment2 weeks ago“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng