China Insight

Twists and Turns in the Tragic Story of the Xuzhou Chained Mother

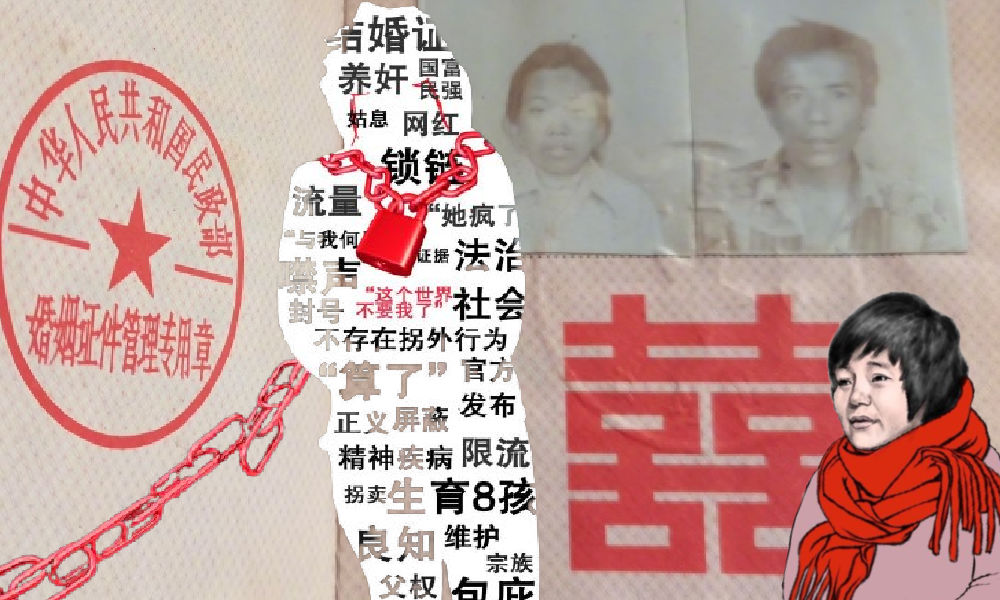

There are still many questions about the Xuzhou woman, but what is clear is that she now has come to represent many women like her.

Published

2 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

It’s been three weeks and there were four official statements, but the story of the Xuzhou mother-of-eight is still seeing new developments, and it is sparking even more anger on Chinese social media.

While the Beijing Olympics are still in full swing, many on Chinese social media are focused on developments taking place some 430 miles south of the capital. Three weeks after the story of a mother of eight children being chained up in a hut next to the family home first sent shockwaves across Chinese social media, the Xuzhou chained mother is still one of the biggest topics discussed on Weibo.

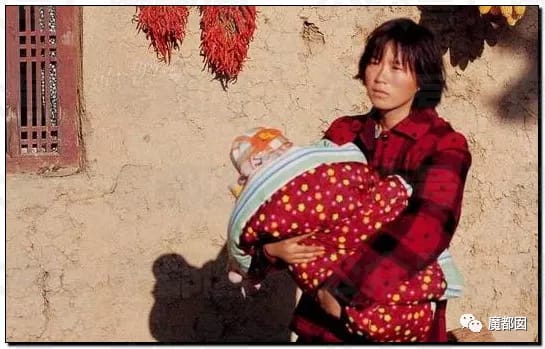

The ball started rolling in late January of this year when a video of the woman, filmed by a local TikTok user, went viral online and triggered massive outrage with thousands of people demanding answers about the woman’s circumstances. The woman, who seemed confused, was kept in a dirty shed without a door in the freezing cold – she did not even wear a coat. Videos showed how her husband Dong Zhimin (董志民) and their eight children were playing and talking in the family home right next to the hut. These videos were all filmed in the village of Huankou.

What’s on Weibo first reported this trending topic on January 29, and after BBC also reported the story on January 31st, the Xuzhou mother also started making international headlines. Meanwhile, on Chinese social media, updates to new developments in the story continued to go viral.

A Douyin vlogger exposed the living conditions of this mother of eight in a small village in Xuzhou. Heartbreaking and inhumane – she was literally chained up and left out in the cold. Full story here: https://t.co/AzCHwBU6mU pic.twitter.com/WLLhjpd4Zr

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) January 29, 2022

Local authorities in Xuzhou, the largest city of northern Jiangsu, and the Feng county-level division, where the village of Huankou is located, started looking into the case after the video went trending. The first statement by Feng County was issued on January 28 and it said that the woman, named Yang (杨), married her husband Dong Zhimin in 1998 and that there was no indication that she was a victim of human trafficking, which was a concern raised by so many netizens.

The woman was dealing with mental problems and would display sudden violent outbursts, beating children and older people. The family allegedly thought it was best to separate her from the family home during these episodes, letting her stay chained up in a small hut next to the house.

The first statement raised more questions than it answered. Many people on Weibo were angry and drew comparisons to the 2007 movie Blind Mountain (盲山). That movie, directed by Li Yang (李杨), tells the story of a woman named Bai who is kidnapped and sold to a villager in the mountains, leaving Bai completely trapped.

Scene from Blind Mountain.

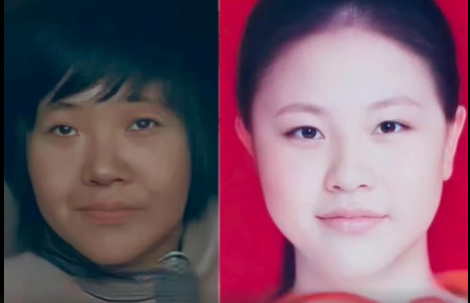

Netizens started to do their own research and suggested that ‘Yang’ could actually be Li Ying (李莹), a woman who went missing in Sichuan’s Nanchong 26 years ago. Online, many people called for DNA research to see if Yang was indeed related to Li Ying’s family.

The mother of eight in Xuzhou compared to the missing woman Li Ying.

While netizens were speculating about the case, it became clear that the husband Dong Zhimin was giving more interviews about his eight children (seven sons, one daughter), spoke of how his sons would become providers for the family in the future, and even promoted local companies. This only led to more speculation and online anger, and Weibo shut down some of the hashtags dedicated to this topic.

More Statements

On January 30, Feng County local officials responded to the controversy in a second statement, in which the Xuzhou mother was identified as Yang *Xia (杨某侠) who allegedly once was “a beggar on the streets” in the summer of 1998 when she was taken in by Dong family and ended up marrying their 30-something son Dong Zhimin.

Local officials did not properly check and verify Yang’s identity information when registering the marriage certificate and the local family planning department also made errors in implementing birth control measures and following up with the family.

Yang did have mental problems before, but her condition allegedly worsened in June of 2021 when she displayed more aggressive behavior and was tied up in the shed. The statement said that Yang had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and was receiving treatment.

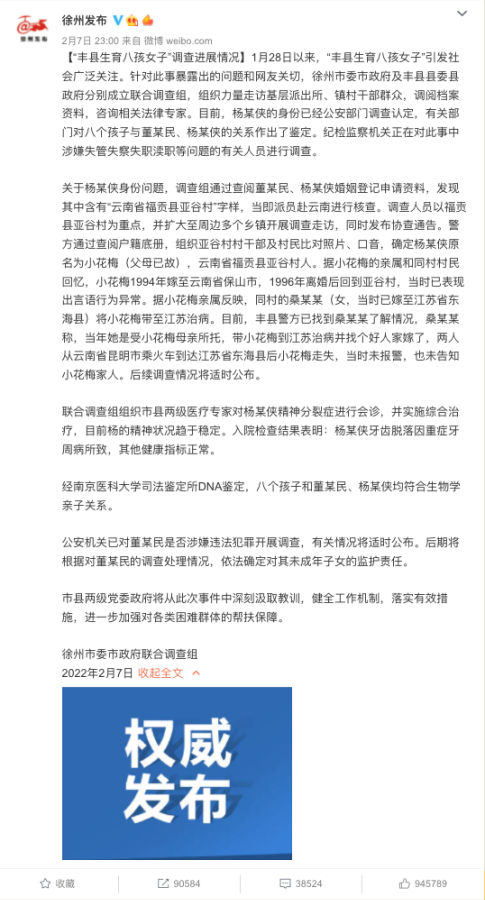

On February 7th, Xuzhou authorities released a third statement with an update of their investigation, which had brought them to the village of Yagu (亚谷村) in Yunnan – a place that was mentioned on Yang’s marriage certificate.

With the help of local authorities, villagers, and household registers, they were able to determine Yang’s identity and stated that she was actually Xiao Huamei (小花梅) who was born and raised in Yagu, Fugong county. In 1994, she married and moved to the city of Baoshan, but she divorced and returned to her village two years later.

Her parents, now deceased, ordered a female fellow villager who had married someone from Jiangsu to take Xiao with her to receive treatment and look for a suitable partner for marriage. Although the woman took Xiao with her on a train from Yunnan’s Kunming city to Jiangsu’s Donghai, Xiao allegedly went missing shortly after arrival. The woman, named Sang (桑), never reported Xiao Huamei missing to the police and she also did not notify Xiao’s family.

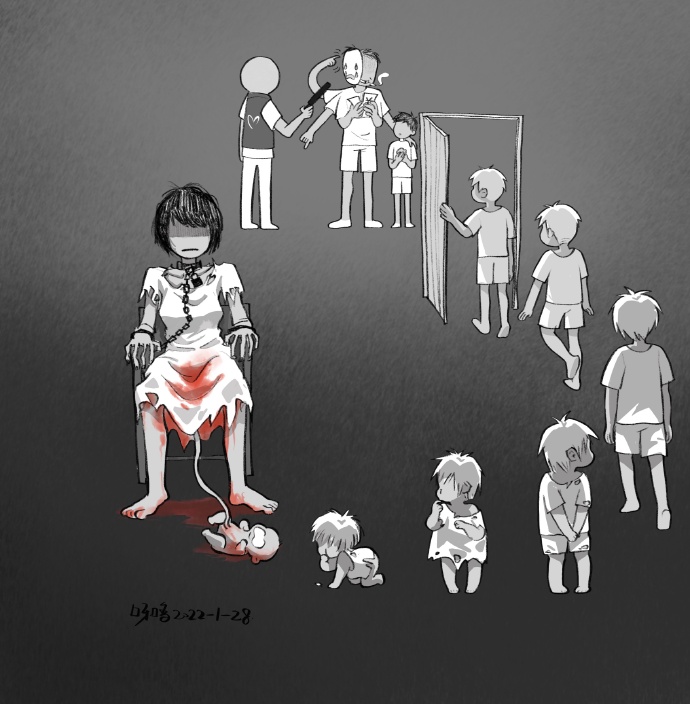

The Xuzhou authorities further write that DNA research has confirmed that all of the eight children are the parents’ biological children.

A fourth statement was issued on February 10th through the Xuzhou official Weibo channel (@徐州发布). According to that statement, Yang’s DNA had been compared to that of the family of Xiao Huamei and it was determined that Yang and Xiao Huamei were definitely the same person.

The statement further said that three persons were held criminally responsible for illegal detainment and human trafficking in the case of Xiao Huamei: Sang, her husband, and Dong Zhimin, the father of the eight children.

Meanwhile, Chinese news outlet The Paper reported that the family of Li Ying, the missing woman who resembled Yang so much, received official confirmation that there was no DNA match between Li Ying and Yang.

Weibo Detectives and Journalists

Following the last statement, online anger did not subside. Was Yang’s husband only accused of ‘illegal detention’? What about rape and abuse?

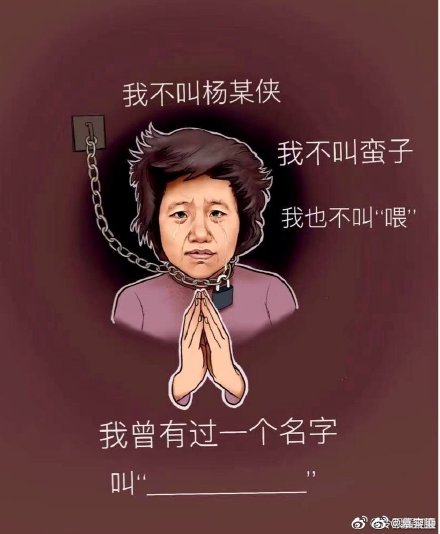

By now, there are multiple stories going around the Chinese internet of other women living in Xuzhou who might have also been a victim of human trafficking. What about them? What are their names? Who cares about them? Who is still out there looking for them?

Another issue raised by Weibo users was that of the age of Xiao Huamei, which was never mentioned in the official statement. Was Xiao Huamei underage when she was trafficked? How old is the Xuzhou mother of eight?

Determined to find out the truth, some investigative journalists and concerned netizens decided to do their own research.

Two Weibo users (using the accounts @小梦姐姐小拳拳, @乌衣古城, and @我能抱起120斤) drove to Feng County, Xuzhou, with the goal of verifying the information disclosed by the local government and pressuring them to arrest husband Dong for his crime. The women, who had been sharing all details of their trip on Weibo, were planning on visiting Yang and talking to other people in the area.

After they arrived in Feng County, the local police allegedly removed the slogans they had written on their own car, calling for Dong’s arrest. They were denied entrance at the facility where Yang supposedly is treated and someone tried to take their phone. When the two women went to the police station to report the attempted phone robbery, the police detained them for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” (“寻衅滋事罪”). A supertopic on Weibo dedicated to helping the two women was taken offline.

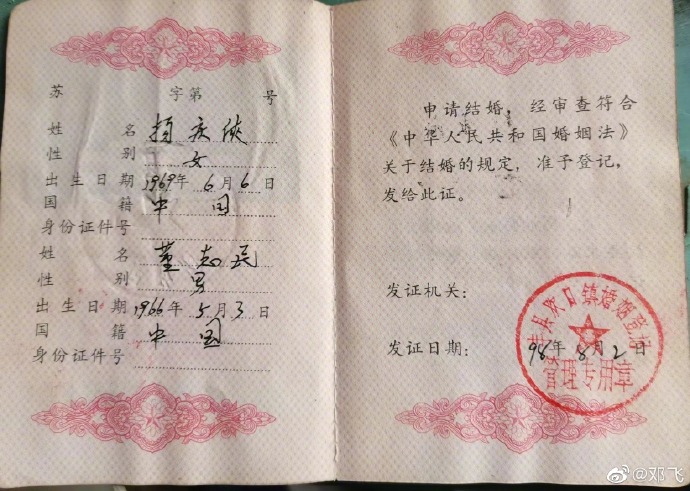

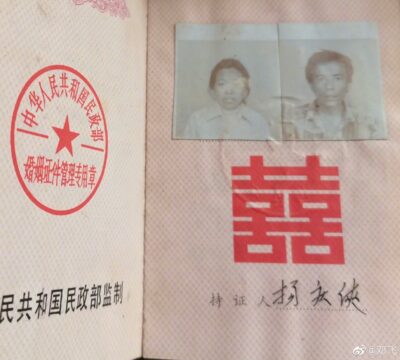

One other important person dedicated to this case is the Chinese investigative journalist Deng Fei (邓飞), who has over five million followers on his Weibo account. On February 13, Deng said that according to Yang’s verified ID card, which he obtained via online channels, her date of birth is June 6, 1969. This means Yang’s age would be 52.

The photo on Yang’s ID card, which says she was born in 1969.

Deng and others questioned Yang’s age, especially considering their youngest baby just turned two. Would a woman in her mid and late 40s, living in such harsh conditions, still be able to have multiple babies? Why was her hair not greying at all? Were authorities lying about her age?

Deng Fei later obtained and published a photo of the marriage certificate of ‘Yang Qingxiang’ and ‘Dong Zhimin,’ which shows their marriage was registered in August of 1998 and was approved by the Huankou township. Here, Yang’s date of birth is also said to be June of 1969. However, what struck Deng and many others is that the photo on the marriage certificate seems to be a different woman from Yang.

The well-known screenwriter and author Li Yaling (@李亚玲) also researched the Xuzhou case, and she claimed that according to her sources, Xiao Huamei was born in 1977 and was initially sold to another man by Sang for 6000 yuan ($950) before she ended up marrying Dong. Li also claims that the vlogger who filmed the first viral video put the chains around the woman’s neck himself. The chains were already there, and were in fact used to sometimes tie up the mother, but they were allegedly only put on her to help get more attention for the woman and her impoverished family.

The account of the vlogger who originally posted the viral video has since been deleted.

After three weeks of developments and four statements later, there are still so many questions, and there are still many doubts about whether or not Xiao Huamei from Yagu village is really Yang from Huankou village, and who the woman in the photo is.

Another issue raised is that the oldest son of the family, Dong *gang (董某港) was born in March of 1997, but according to one of the earlier statements issued in this case, Dong Zhimin’s father took in Yang in the summer of 1998 and their marriage certificate was issued in August of that year. So whose child is the oldest kid?

Many people think that perhaps Xiao Huamei – who was trafficked in 1996 – was actually once married to Dong and is the mother of the oldest child, but that the chained mother in Xuzhou is another woman. Since Xiao Huamei was married before in 1994, the ex-husband could surely confirm if Yang in Xuzhou is indeed the woman he was once married to, but so far his identity has not been disclosed.

The Women in the Dark Rooms

While details surrounding the case of the ‘chained Xuzhou mother of eight’ are still being discussed a lot, it has become clear that by now, Yang has come to represent many more women like her.

Since early February, more stories have surfaced of other women like Yang, often suffering from a mental or physical handicap. One of these stories involved a disabled woman also from Xuzhou, Feng County – a video that showed her lying on the floor also went viral on social media including a second video showing the woman living in terrible conditions, although there has not been a follow-up on her specific situation.

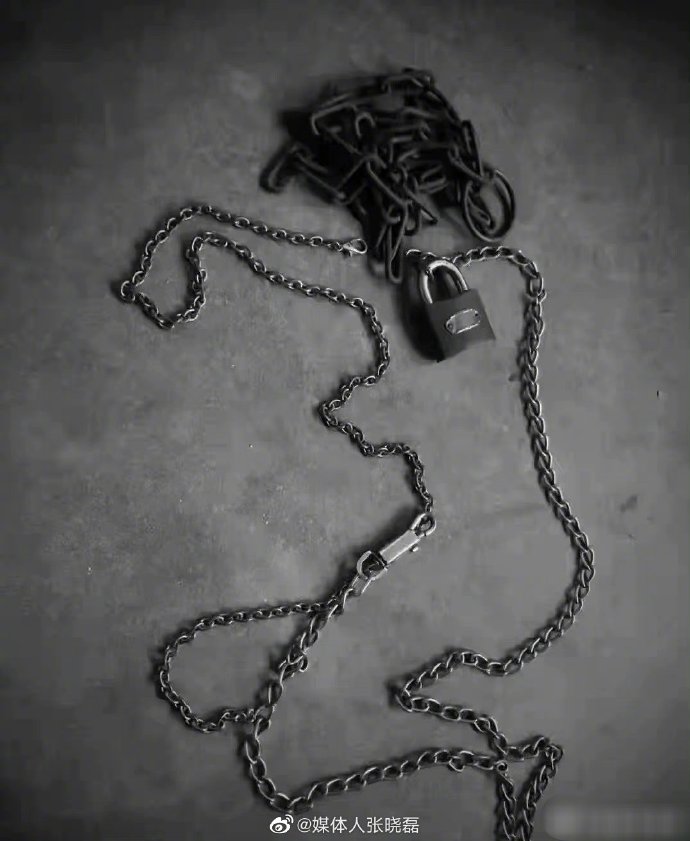

In light of the recent developments, media insider Zhang Xiaolei (@媒体人张晓磊) posted a segment of a TV documentary from ten years ago on Weibo titled “The Woman Leaving the Dark Room” (走出黑屋的女人), in which a naked and confused middle-aged woman was kept locked in a hut in a village in Shandong province, just a one-hour drive from Huankou village. Zhang wrote that the reporter, with the help of local authorities, was able to rescue the woman and eventually succeeded in locating her family.

Still from the decade-old documentary (走出黑屋的女人) about a woman kept in a small house, just 40 kilometers away from where the Xuzhou mother of eight lived.

Zhang’s post was taken offline, as were other initiatives to raise more awareness. On Valentine’s Day, a group of people from Yueyang, Hunan, spoke up for the Xuzhou mother and posted a group photo in which they carried banners and hashtagged the post “stand up for human rights.” That post was also soon deleted, along with a letter signed by 10 graduates of Peking University to call for an investigation of local officials involved in the case, changes to the law, and more details on the Xuzhou woman’s identity.

Despite censorship, netizens keep posting about the case and putting pressure on authorities to do more research and take more action. How could Yang have been so neglected? Why didn’t authorities do more to prevent such a tragedy from happening?

Their calls do seem to have some impact, as the higher authorities of Jiangsu provincial government have reportedly now also decided to set up an investigation team to conduct an investigation into the Xuzhou case.

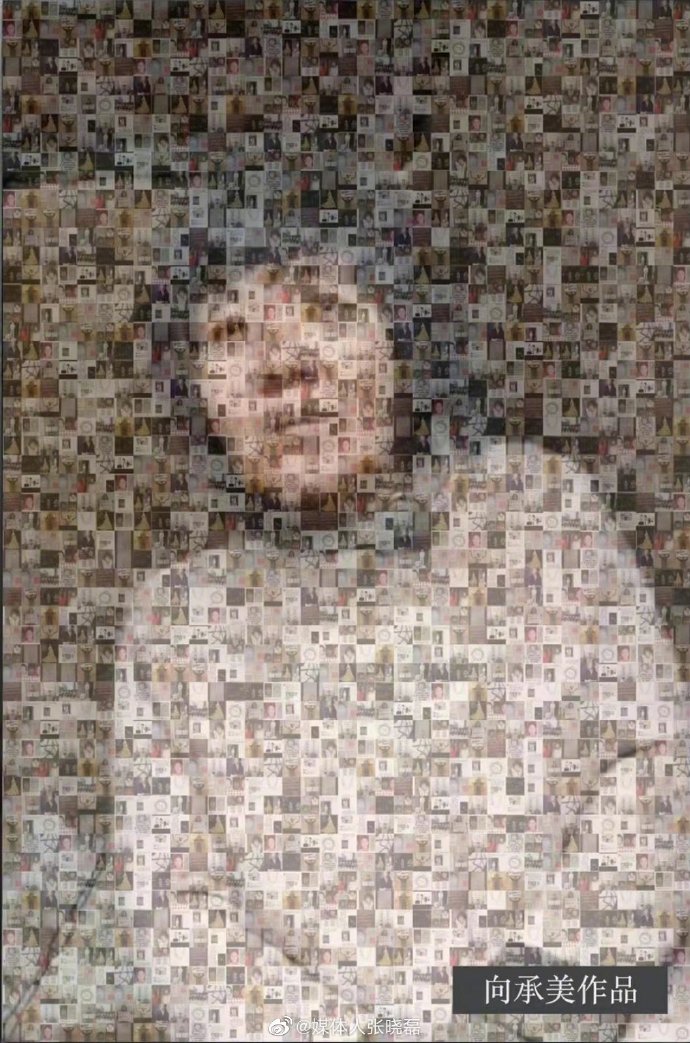

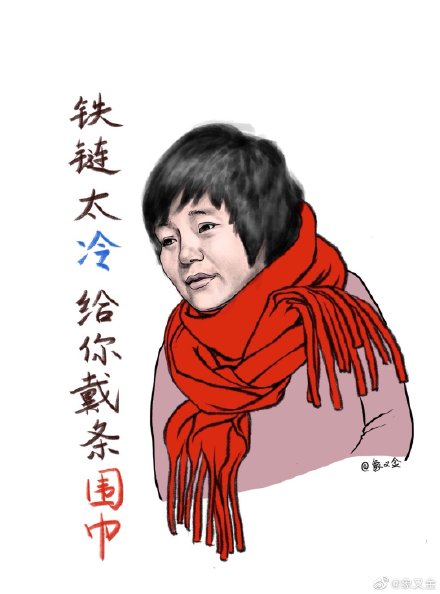

Meanwhile, there are many artists who are using their artwork, from sculptures to graphic design, to express their feelings about the case and condemn how local authorities have dealt with this case.

They also pay their respects to the chained-up woman in the video. Regardless of who she is, and how she got there, there is one thing everyone agrees on; her story is a tragic one, and no matter who gets punished for what happened to her, there are no winners here.

By Manya Koetse

With contributions by Miranda Barnes.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy.

Published

1 day agoon

May 3, 2024

It seemed like such a good idea. For this year’s World Book Day, Chinese tea brand LELECHA (乐乐茶) put a spotlight on Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881-1936), one of the most celebrated Chinese authors the 20th century and turned him into the the ‘brand ambassador’ of their special new “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙) milk tea.

LELECHA is a Chinese chain specializing in new-style tea beverages, including bubble tea and fruit tea. It debuted in Shanghai in 2016, and since then, it has expanded rapidly, opening dozens of new stores not only in Shanghai but also in other major cities across China.

Starting on April 23, not only did the LELECHA ‘Smoky Oolong” paper cups feature Lu Xun’s portrait, but also other promotional materials by LELECHA, such as menus and paper bags, accompanied by the slogan: “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” (“老烟腔,新青年”). The marketing campaign was a joint collaboration between LELECHA and publishing house Yilin Press.

Lu Xun featured on LELECHA products, image via Netease.

The slogan “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” is a play on the Chinese magazine ‘New Youth’ or ‘La Jeunesse’ (新青年), the influential literary magazine in which Lu’s famous short story, “Diary of a Madman,” was published in 1918.

The design of the tea featuring Lu Xun’s image, its colors, and painting style also pay homage to the era in which Lu Xun rose to prominence.

Lu Xun (pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a leading figure within China’s May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1915-24) is also referred to as the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance. It was the cultural revolution brought about by the political demonstrations on the fourth of May 1919 when citizens and students in Beijing paraded the streets to protest decisions made at the post-World War I Versailles Conference and called for the destruction of traditional culture[1].

In this historical context, Lu Xun emerged as a significant cultural figure, renowned for his critical and enlightened perspectives on Chinese society.

To this day, Lu Xun remains a highly respected figure. In the post-Mao era, some critics felt that Lu Xun was actually revered a bit too much, and called for efforts to ‘demystify’ him. In 1979, for example, writer Mao Dun called for a halt to the movement to turn Lu Xun into “a god-like figure”[2].

Perhaps LELECHA’s marketing team figured they could not go wrong by creating a milk tea product around China’s beloved Lu Xun. But for various reasons, the marketing campaign backfired, landing LELECHA in hot water. The topic went trending on Chinese social media, where many criticized the tea company.

Commodification of ‘Marxist’ Lu Xun

The first issue with LELECHA’s Lu Xun campaign is a legal one. It seems the tea chain used Lu Xun’s portrait without permission. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s great-grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation, quickly demanded an end to the unauthorized use of Lu Xun’s image on tea cups and other merchandise. He even hired a law firm to take legal action against the campaign.

Others noted that the image of Lu Xun that was used by LELECHA resembled a famous painting of Lu Xun by Yang Zhiguang (杨之光), potentially also infringing on Yang’s copyright.

But there are more reasons why people online are upset about the Lu Xun x LELECHA marketing campaign. One is how the use of the word “smoky” is seen as disrespectful towards Lu Xun. Lu Xun was known for his heavy smoking, which ultimately contributed to his early death.

It’s also ironic that Lu Xun, widely seen as a Marxist, is being used as a ‘brand ambassador’ for a commercial tea brand. This exploits Lu Xun’s image for profit, turning his legacy into a commodity with the ‘smoky oolong’ tea and related merchandise.

“Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you in an article. ”

On April 29, LELECHA finally issued an apology to Lu Xun’s relatives and the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation for neglecting the legal aspects of their marketing campaign. They claimed it was meant to promote reading among China’s youth. All Lu Xun materials have now been removed from LELECHA’s stores.

Statement by LELECHA.

On Chinese social media, where the hot tea became a hot potato, opinions on the issue are divided. While many netizens think it is unacceptable to infringe on Lu Xun’s portrait rights like that, there are others who appreciate the merchandise.

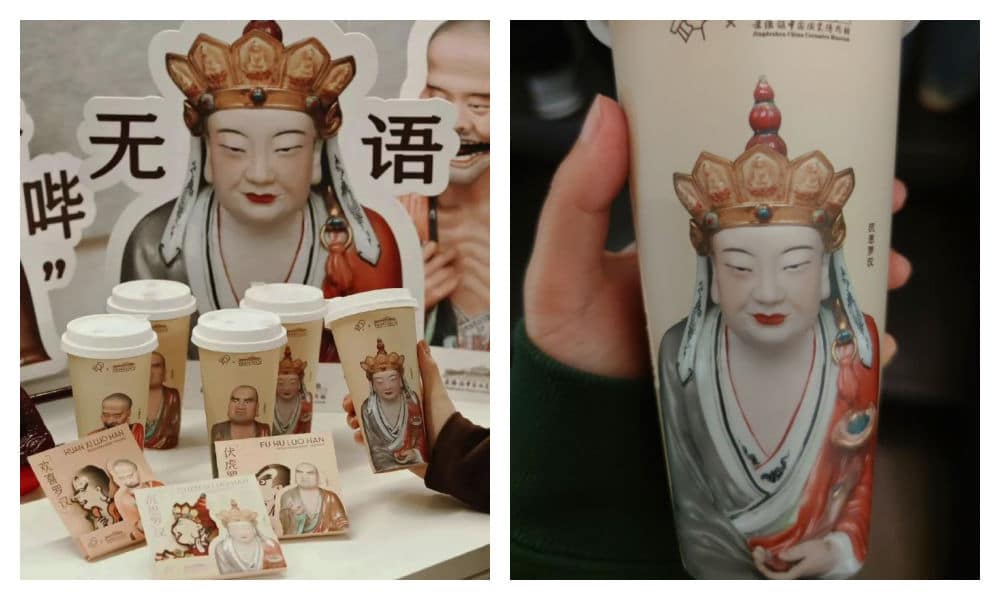

The LELECHA controversy is similar to another issue that went trending in late 2023, when the well-known Chinese tea chain HeyTea (喜茶) collaborated with the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum to release a special ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ (佛喜) latte tea series adorned with Buddha images on the cups, along with other merchandise such as stickers and magnets. The series featured three customized “Buddha’s Happiness” cups modeled on the “Speechless Bodhisattva” (无语菩萨), which soon became popular among netizens.

The HeyTea Buddha latte series, including merchandise, was pulled from shelves just three days after its launch.

However, the ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ success came to an abrupt halt when the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Shenzhen intervened, citing regulations that prohibit commercial promotion of religion. HeyTea wasted no time challenging the objections made by the Bureau and promptly removed the tea series and all related merchandise from its stores, just three days after its initial launch.

Following the Happy Buddha and Lu Xun milk tea controversies, Chinese tea brands are bound to be more careful in the future when it comes to their collaborative marketing campaigns and whether or not they’re crossing any boundaries.

Some people couldn’t care less if they don’t launch another campaign at all. One Weibo user wrote: “Every day there’s a new collaboration here, another one there, but I’d just prefer a simple cup of tea.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Schoppa, Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia UP, 159.

[2]Zhong, Xueping. 2010. “Who Is Afraid Of Lu Xun? The Politics Of ‘Debates About Lu Xun’ (鲁迅论争lu Xun Lun Zheng) And The Question Of His Legacy In Post-Revolution China.” In Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China, 257–284, 262.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Zibo had its BBQ moment. Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine with its special take on malatang. Tourism marketing in China will never be the same again.

Published

1 month agoon

April 1, 2024

Since the early post-pandemic days, Chinese cities have stepped up their game to attract more tourists. The dynamics of Chinese social media make it possible for smaller, lesser-known destinations to gain overnight fame as a ‘celebrity city.’ Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine.

During this Qingming Festival holiday, there is one Chinese city that will definitely welcome more visitors than usual. Tianshui, the second largest city in Gansu Province, has emerged as the latest travel hotspot among domestic tourists following its recent surge in popularity online.

Situated approximately halfway along the Lanzhou-Xi’an rail line, this ancient city wasn’t previously a top destination for tourists. Most travelers would typically pass through the industrial city to see the Maiji Shan Grottoes, the fourth largest Buddhist cave complex in China, renowned for its famous rock carvings along the Silk Road.

But now, there is another reason to visit Tianshui: malatang.

Gansu-Style Malatang

Málàtàng (麻辣烫), which literally means ‘numb spicy hot,’ is a popular Chinese street food dish featuring a diverse array of ingredients cooked in a soup base infused with Sichuan pepper and dried chili pepper. There are multiple ways to enjoy malatang.

When dining at smaller street stalls, it’s common to find a selection of skewered foods—ranging from meats to quail eggs and vegetables—simmering in a large vat of flavorful spicy broth. This communal dining experience is affordable and convenient for solo diners or smaller groups seeking a hotpot-style meal.

In malatang restaurants, patrons can usually choose from a selection of self-serve skewered ingredients. You have them weighed, pay, and then have it prepared and served in a bowl with a preferred soup base, often with the option to choose the level of spiciness, from super hot to mild.

Although malatang originated in Sichuan, it is now common all over China. What makes Tianshui malatang stand out is its “Gansu-style” take, with a special focus on hand-pulled noodles, potato, and spicy oil.

An important ingredient for the soup base is the somewhat sweet and fragrant Gangu chili, produced in Tianshui’s Gangu County, known as “the hometown of peppers.”

Another ingredient is Maiji peppercorns (used in the sauce), and there are more locally produced ingredients, such as the black fungi from Qingshui County.

One restaurant that made Tianshui’s malatang particularly famous is Haiying Malatang (海英麻辣烫) in the city’s Qinzhou District. On February 13, the tiny restaurant, which has been around for three decades, welcomed an online influencer (@一杯梁白开) who posted about her visit.

The vlogger was so enthusiastic about her taste of “Gansu-style malatang,” that she urged her followers to try it out. It was the start of something much bigger than she could have imagined.

Replicating Zibo

Tianshui isn’t the first city to capture the spotlight on Chinese social media. Cities such as Zibo and Harbin have previously surged in popularity, becoming overnight sensations on platforms like Weibo, Xiaohongshu, and Douyin.

This phenomenon of Chinese cities transforming into hot travel destinations due to social media frenzy became particularly noteworthy in early 2023.

During the Covid years, various factors sparked a friendly competition among Chinese cities, each competing to attract the most visitors and to promote their city in the best way possible.

The Covid pandemic had diverse impacts on the Chinese domestic tourism industry. On one hand, domestic tourism flourished due to the pandemic, as Chinese travelers opted for destinations closer to home amid travel restrictions. On the other hand, the zero-Covid policy, with its lockdowns and the absence of foreign visitors, posed significant challenges to the tourism sector.

Following the abolition of the zero-Covid policy, tourism and marketing departments across China swung into action to revitalize their local economy. China’s social media platforms became battlegrounds to capture the attention of Chinese netizens. Local government officials dressed up in traditional outfits and created original videos to convince tourists to visit their hometowns.

Zibo was the first city to become an absolute social media sensation in the post-Covid era. The old industrial and mining city was not exactly known as a trendy tourist destination, but saw its hotel bookings going up 800% in 2023 compared to pre-Covid year 2019. Among others factors contributing to its success, the city’s online marketing campaign and how it turned its local BBQ culture into a unique selling point were both critical.

Zibo crowds, image via 163.com.

Since 2023, multiple cities have tried to replicate the success of Zibo. Although not all have achieved similar results, Harbin has done very well by becoming a meme-worthy tourist attraction earlier in 2024, emphasizing its snow spectacle and friendly local culture.

By promoting its distinctive take on malatang, Tianshui has emerged as the next city to captivate online audiences, leading to a surge in visitor numbers.

Like with Zibo and Harbin, one particular important strategy used by these tourist offices is to swiftly respond to content created by travel bloggers or food vloggers about their cities, boosting the online attention and immediately seizing the opportunity to turn online success into offline visits.

A Timeline

What does it take to become a Chinese ‘celebrity city’? Since late February and early March of this year, various Douyin accounts started posting about Tianshui and its malatang.

They initially were the main reason driving tourists to the city to try out malatang, but they were not the only reason – city marketing and state media coverage also played a role in how the success of Tianshui played out.

Here’s a timeline of how its (online) frenzy unfolded:

- July 25, 2023: First video on Douyin about Tianshui’s malatang, after which 45 more videos by various accounts followed in the following six months.

- Feb 5, 2024: Douyin account ‘Chuanshuo Zhong de Bozi’ (传说中的波仔) posts a video about malatang streetfood in Gansu

- Feb 13, 2024: Douyin account ‘Yibei Liangbaikai’ (一杯梁白开) posts a video suggesting the “nationwide popularization of Gansu-style malatang.” This video is an important breakthrough moment in the success of Tianshui as a malatang city.

- Feb – March ~, 2024: The Tianshui Culture & Tourism Bureau is visiting sites, conducting research, and organizing meetings with different departments to establish the “Tianshui city + malatang” brand (文旅+天水麻辣烫”品牌) as the city’s new “business card.”

- March 11, 2024: Tianshui city launches a dedicated ‘spicy and hot’ bus line to cater to visitors who want to quickly reach the city’s renowned malatang spots.

- March 13-14, 2024: China’s Baidu search engine witnesses exponential growth in online searches for Tianshui malatang.

- March 14-15, 2024: The boss of Tianshui’s popular Haiying restaurant goes viral after videos show him overwhelmed and worried he can’t keep up. His facial expression becomes a meme, with netizens dubbing it the “can’t keep up-expression” (“烫不完表情”).

The worried and stressed expression of this malatang diner boss went viral overnight.

- March 17, 2024: Chinese media report about free ‘Tianshui malatang’ wifi being offered to visitors as a special service while they’re standing in line at malatang restaurants.

- March 18, 2024: Tianshui opens its first ‘Malatang Street’ where about 40 stalls sell malatang.

- March 18, 2024: Chinese local media report that one Tianshui hair salon (Tony) has changed its shop into a malatang shop overnight, showing just how big the hype has become.

- March 21, 2024: A dedicated ‘Tianshui malatang’ train started riding from Lanzhou West Station to Tianshui (#天水麻辣烫专列开行#).

- March 21, 2024: Chinese actor Jia Nailiang (贾乃亮) makes a video about having Tianshui malatang, further adding to its online success.

- March 30, 2024: A rare occurrence: as the main attraction near Tianshui, the Maiji Mountain Scenic Area announces that they’ve reached the maximum number of visitors and don’t have the capacity to welcome any more visitors, suspending all ticket sales for the day.

- April 1, 2024: Chinese presenter Zhang Dada was spotted making malatang in a local Tianshui restaurant, drawing in even more crowds.

A New Moment to Shine

Fame attracts criticism, and that also holds true for China’s ‘celebrity cities.’

Some argue that Tianshui’s malatang is overrated, considering the richness of Gansu cuisine, which offers much more than just malatang alone.

When Zibo reached hype status, it also faced scrutiny, with some commenters suggesting that the popularity of Zibo BBQ was a symptom of a society that’s all about consumerism and “empty social spectacle.”

There is a lot to say about the downsides of suddenly becoming a ‘celebrity city’ and the superficiality and fleetingness that comes with these kinds of trends. But for many locals, it is seen as an important moment as they see their businesses and cities thrive.

Even after the hype fades, local businesses can maintain their success by branding themselves as previously viral restaurants. When I visited Zibo a few months after its initial buzz, many once-popular spots marketed themselves as ‘wanghong’ (网红) or viral celebrity restaurants.

For the city itself, being in the spotlight holds its own value in the long run. Even after the hype has peaked and subsided, the gained national recognition ensures that these “trendy” places will continue to attract visitors in the future.

According to data from Ctrip, Tianshui experienced a 40% increase in tourism spending since March (specifically from March 1st to March 16th). State media reports claim that the city saw 2.3 million visitors in the first three weeks of March, with total tourism revenue reaching nearly 1.4 billion yuan ($193.7 million).

There are more ripple effects of Tianshui’s success: Maiji Shan Grottoes are witnessing a surge in visitors, and local e-commerce companies are experiencing a spike in orders from outside the city. Even when they’re not in Tianshui, people still want a piece of Tianshui.

By now, it’s clear that tourism marketing in China will never be the same again. Zibo, Harbin, and Tianshui exemplify a new era of destination hype, requiring a unique selling point, social media success, strong city marketing, and a friendly and fair business culture at the grassroots level.

While Zibo’s success was largely organic, Harbin’s was more orchestrated, and Tianshui learned from both. Now, other potential ‘celebrity’ cities are preparing to go viral, learning from the successes and failures of their predecessors to shine when their time comes.

By Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

The Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight2 months ago

China Insight2 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

-

China Arts & Entertainment2 weeks ago

China Arts & Entertainment2 weeks ago“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

-

China Media2 months ago

China Media2 months agoParty Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

reader

February 18, 2022 at 9:59 pm

Menanwhile -> meanwhile

Great, enlightening yet concise write-up

thank you

goed gedaan

Admin

February 20, 2022 at 6:36 pm

Thanks so much for noticing, adjusted!

Sam

February 19, 2022 at 6:46 pm

No one believes this still happen in a 21st century in China, and I am extremely outrageous after reading this story, and can not find word for this kind of cruelty, immoral and illegal behavior in rural area. Everyone need to keep following this for answers and steps to complete saving of thousands of similar women in China. The gender imbalance due to the one cold policy has resulted in this kind of human trafficking of women in China’s rural areas.