Weiblog

Chinese Government Declares New National Holiday

The year 2015 has a special meaning for Chinese People, as it has been 70 years since the end of the war. The Chinese Government Declares New National Holiday.

Published

9 years agoon

The year 2015 has a special meaning for Chinese People, as it has been 70 years since the end of the war.

The Chinese government has therefore declared a new national holiday on September 3th this year, commemorating the 70th Anniversary of the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War, that merged into WWII when China joined the Allies in 1941. This war, that is also called the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japan (中国人民抗日战争), ended in September 1945.

September 3th has been made into a holiday for the public to participate in the commemorations held by the central government and those organized by local departments in different cities around China. It follows directly after Victory over Japan Day on September 2.

According to the new schedule, Thursday, September 3th, will be observed as a national holiday, followed by two more days of vacation on Friday, September 4, and Saturday, September 5. Sunday, September 6, will be a make-up work day.

The State Council of China has pointed out that departments working in duty, security and safeguarding fields must be arranged well by in all places; they must prepare for unexpected big incidents, and proper measures must be taken to ensure all commemorations across the nation can be held smoothly.

The topic became trending on Sina Weibo (#9月3日全国放假#), with many netizens expressing their support for the commemoration and their joy with an extra free day. For some netizens, however, one day of commemoration is not enough: “I think that one day of commemoration is not enough to express our joy with the victory of war (..),” one netizens says*: “Aren’t August 15th [Japan’s surrender to the Allies in 1945] and September 18th [the Mukden Incident] also important dates? Won’t we commemorate them? I think we should have a holiday from August 15 until September 18, then we can really enjoy the happiness of peace..”

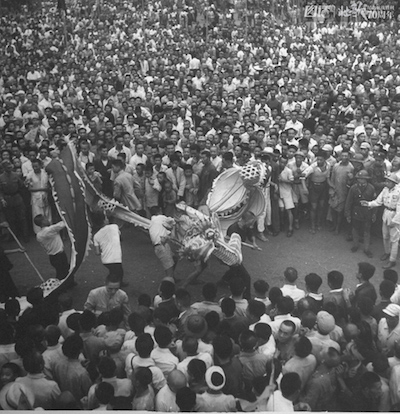

Tencent News published some historical pictures from the end of the war in 1945 China in the light of the news of the national commemorations this year.

Chinese crowds celebrating surrender of Japan on Victory over Japan Day in Chongqing (Photo by Jack Wilkes, Getty Images).

The celebrations of the end of the Second World War did not last long everywhere, as the nation erupted in civil war. On this picture, you can see the army troops entering Guangzhou after the Japanese have left.

Chinese Americans on Mott and Pell Streets in New York’s Chinatown celebrate after learning that the Japanese have surrendered to the Allies, on Victory over Japan Day, Aug. 14, 1945 (AP Photo/Tom Fitzsimmons).

Crowds of joyous Chinese make a sea of hands as they wave their during Chongqing victory celebrations, after receiving the news that the Japanese in Chongqing surrendered (August 29, 1945). Many of them can be seen making the V- sign (AP Photo).

Celebrations in Shanghai: teahouses gave out free tea, merchants gave out free flags to celebrate the Japanese surrender (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images).

War correspondent Palmer Hoyt and his girlfriend Barbara Stephens, celebrating in Chongqing, October 1945. (Photo by Jack Wilkes/Getty Images)

Chinese crowds celebrate Victory over Japan Day in 1945, with some performing the Dragon Dance. (Photo by Jack Wilkes/Getty Images).

Featured Image:

Parade in Chongqing, Celebrations in China of Victory over Japan Day September 3, 1945: http://news.qq.com/original/tuhua/shengliri.html

*”我觉得吧,九月三日胜利纪念日当天放假并不足以表达我们对胜利的喜悦,以及对和平的祈愿,日本也很慢再着短短一天里吸取什么教训。而八月十五日和九月十八日难道不也是重要的日子吗?难道就不去铭记了?所以应该从八月十五日放到九月十八日,让我们在这一个月里好好感受和平的幸福与来之不易不更好吗~”

[box] This is Weiblog: the What’s on Weibo short-blog section. Brief daily updates on our blog and what is currently trending on China’s biggest social medium, Sina Weibo.[/box]

©2015 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

Newsletter

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

The future is here, but it looks different than we expected. This Weibo Watch covers driverless taxis and other noteworthy, popular topics.

Published

4 days agoon

July 23, 2024

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #33

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – The future is here

◼︎ 2. What’s New and Noteworthy – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s Remarkable – A panicked mum goes to extremes

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – The passing of Cheng Peipei

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Virtual news anchors

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – Bye bye, Biden

Dear Reader,

The future is here, and it is all unfolding so much differently than we could have imagined.

Scrolling through Douyin and Weibo’s video feeds recently, there are hundreds of videos about China’s self-driving taxi revolution. The wonder and excitement over the unmanned cabs is not surprising – it is the biggest thing happening in China’s taxi industry since ride-hailing apps Didi, Kuaidi, and Uber first entered the Chinese market over a decade ago.

Luobo Kuaipao (萝卜快跑) by Baidu, called ‘Apollo Go’ in English, is the ‘robotaxi’ ride-hailing platform that is now generating the most attention online. The concept is simple: customers order the taxi via the app and enter their destination, it arrives at the meeting point, and via a panel on the side of the car, the customer inserts the last four digits of their phone number. The door then automatically opens, and they can get in the car, which will take them to where they want to go. The car is private, and the price is comparable to ride-sharing fees, but then cheaper.

There is an additional benefit: the cars are equipped with a “smart cockpit”, allowing passengers to start their journey by tapping the screen in front of them, selecting a podcast or their favorite music, controlling the air-conditioning, and watching the traffic while en route.

Currently, Luobo Kuaipao has some 500 robotaxis operating without safety drivers in Wuhan, now the world’s largest city for driverless taxis. Baidu plans to expand this fleet with an additional 1,000 robotaxis soon. Shanghai will also launch a public testing program for driverless taxi services by SAIC in the upcoming week.1

Across China, at least 16 cities are now testing self-driving vehicles, with at least 19 Chinese car manufacturers competing for global leadership. Nationwide, 20 provinces have already released policies and regulations for autonomous driving.23

In many bigger Chinese cities, smart autonomous vehicles are already part of daily life. For years now, autonomous cleaning cars have been a common sight in popular tourist spots. I remember seeing a cute little car working hard to clean the area around the Terracotta Warrior museum in Xi’an in 2019. There are also self-driving tourist shuttles, driverless trucks operating between Beijing and Tianjin, and AI-driven service carts that precisely know where crowds gather during lunch breaks, stop when people wave, and process mobile payments for hamburgers or chicken salads on the spot.

So far, so ‘futuristic.’

But it’s not all roses. Besides the many enthusiastic videos taken by Chinese riders posting their experiences of taking an unmanned, self-driving taxi for the very first time, the emergence and rising popularity of robotaxis is also leading to worries, complaints, and aggravation.

A commonly heard objection to the unmanned taxis is that they are taking away jobs in the taxi industry. Perhaps even more so than when ChatGPT first emerged, the question of AI replacing people rather than serving them is frequently popping up, with taxi drivers fearing they’ll lose their jobs as robotaxis spread throughout China. These worries can still be countered by the numbers. After all, Wuhan has more than 100,000 registered ride-hailing cars, and Luobo Kuaipao holds just around 0.40% of the market – an insignificant number. 4 But with the rise of the industry, including its competitive prices, that number is bound to change.

Another far more unexpected concern about the rise of China’s robotaxis is that they’re causing chaos in the streets by being ‘too polite.’ These autonomous taxis are trained to follow the traffic rules and act civilized in traffic – something that seems out of place in some areas, where not following the rules almost seems like a rule.

By staying in the right lane, stopping for red lights, and giving priority to other cars, pedestrians, and animals, Chinese robotaxis are causing road congestion and sometimes accidents. They often struggle with complex traffic situations; for example, a viral video showed two Luobo Kuaipao cars waiting for each other to move, holding up traffic. In Wuhan, where drivers are known for their aggressive driving style, these autonomous cars face additional challenges. They strictly follow traffic laws and are not accustomed to pushing their way into traffic, which can lead to long waits for simple turns or merges, causing delays for other drivers.

This behavior has earned them the nickname ‘Sháo Luóbo’ (勺萝卜, “silly radish”), suggesting they are sluggish, or dumb. Although Luobo Kuaipao translates to ‘Radish Runs Fast’ or ‘Carrot Run,’ implying speed and efficiency, the reality is quite different.

Also unexpected is how ‘driverless’ is not what you might have thought it is; because every car still has a “safety operator” who is remotely monitoring it from another location. One person can monitor 10 cars or even more, but they’re allegedly penalized if they close their eyes for more than three seconds.5 Videos and pictures from these robotaxi headquarters sometimes look like old-fashioned game halls or internet cafes.

Complaints about Luobo Kuaipao not being as modern as people hoped and not being as assertive as they thought ultimately boil down to a clash of cultures. Luobo Kuaipao is made in China, but it’s not programmed with the personality and ways of a Wuhan taxi driver. In the end, Wuhan drivers will need to learn from Luobo Kuaipao, and Luobo Kuaipao will need to learn from Wuhan traffic. One side will learn to become more ‘polite,’ while the other will need to add some ‘aggression’ in order to mix in with traffic.

As ‘silly’ as Luobo Kuaipao may seem now, let’s not forget that everything starts small – we all began in diapers. Nothing significant ever came without humble beginnings. The future is here, but what we consider truly ‘futuristic’ will perhaps always be a vision for the days to come.

Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang have contributed to the compilation and interpretation of some topics featured in this week’s newsletter. As always, if you have any observations or ideas you’d like to share, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me.

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

References:

1 Wu Qingqing 吴青青. 2024. “The Luobo Kuaipao Versus Tesla War”[萝卜快跑,与特斯拉终有一战].” Auto Business Review (汽车商业评论), July 18 https://inabr.com/news/19693 [Accessed July 22, 2024].

2 Bradsher, Keith. 2014. “China Is Testing More Driverless Cars Than Any Other Country.” New York Times, June 14 https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/13/business/china-driverless-cars.html [Accessed July 22, 2024].

3 Qi Xu 齐旭. 2024. “Which City is China’s First City for Autonomous Driving? [谁是中国自动驾驶“第一城”?]” China Electronics News 中国电子报, July 16 https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20240716A00W2N00?suid=&media_id= [Accessed July 22, 2024].

4 Wu Qingqing 吴青青. “The Luobo Kuaipao Versus Tesla War.”

5 Jones, Phil. 2014. “Behind Driverless Cars – The Safety Operators Who Can’t Close Their Eyes[无人驾驶车背后,是无法闭眼的安全员].” The Paper, July 19 https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_28124126 [Accessed July 22, 2024].

What’s New

“As smooth as a flying bullet” | The assassination attempt on former US President Trump at a Pennsylvania campaign event also became a major topic on Chinese social media, where Trump’s swift reaction and defiant gesture after the shooting have not only sparked discussions but also fueled the “Comrade Trump” meme machine.

Park with a view | “The ‘sea in Ditan Park’ is a perfect example of how Xiaohongshu netizens use their imagination to change the world,” a recent viral post on Weibo said. This seaview spot in the Beijing public park has become a new ‘check-in spot’ among Chinese Xiaohongshu users and influencers.

From Hollywood to Beijing | For the Dutch national broadcaster’s summer series ‘From Hollywood to Bollywood,’ I spoke about the Chinese blockbuster Battle at Lake Changjin (2021) this week. This spectacular war film depicts the story of Chinese troops during the massive Battle of the Chosin Reservoir in the Korean War, where they encircled and pushed back American forces. The film is an impressive visual spectacle, but it’s a landmark movie in other aspects as well. Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, China is striving to become a global powerhouse in the film industry. At the same time, this film also helped shape new narratives of the Korean War that foster patriotism. Dutch readers can listen to or watch the entire conversation via the link. If you’re interested in learning more about this topic but not that good at understanding Dutch—nobody’s blaming you—check out this article on WoW from our archive.

What’s Trending

JULY 11

🛢️🍳 Cooking Oil Scandal | A major news topic that’s been fermenting over the past month is the revelation that some cooking oil transport trucks in China are also being used for transporting industrial oil. The issue went trending after a publication by Beijing News authored by investigative journalist Han Futao (韩福涛) on July 2, which detailed how the same tanks were used for transporting both edible oils like soybean oil and chemical oils like kerosene without any cleaning process. The food safety scandal sparked outrage online and led to people meticulously tracking the whereabouts of oil tankers and how they operate, while various tanker companies came forward to provide clarity on their procedures. The incident has raised significant awareness about the potential misuse of tankers and intensified concerns about food safety in China.

JULY 15

🚗 Trump Photo Copyrights | After the Trump rally shooting went viral across Chinese media, another trending hashtag emerged regarding the copyright of the iconic ‘raised fist photo,’ shot by award-winning photographer Evan Vucci. Chinese online sources attributed the photo’s rights to the photo agency “Visual China” (视觉中国), allegedly charging 2100 yuan ($288) per use on social media, with threats of lawsuits for unauthorized use. This sparked debates over copyright ownership, as Evan Vucci was not mentioned. In the past, the same company triggered controversy for claiming copyright for an image of the Chinese national flag. They were also sued by a Chinese photographer for claiming ownership of 173 of his photos. Visual China later clarified that they, as a partner of AP, only have distribution rights but do not own the Trump photo.

JULY 16

🌧️ Floods | Thousands of households across China have been affected by floods recently, from Sichuan to Hunan, from Henan to Shaanxi. The city of Xiangyang in Hubei is one such affected area, which experienced its strongest rainfall since the start of the flood season. Some areas nearby broke single day rainfall records, with cars in the streets being swept away by the water. In Henan, floods forced over 100,000 people to evacuate their homes, according to state media. The floods have been catastrophic, especially for farmers, leaving widespread devastation.

JULY 19

🏥 Wenzhou Doctor Killed | A vicious attack on a doctor at the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University has gone viral this week, sending shockwaves across Chinese social media. The incident occurred on the afternoon of July 19, when a man suddenly attacked and stabbed Dr. Li Sheng (李晟), who was on duty in the hospital’s cardiology department. The attacker subsequently jumped off the building. Despite extensive rescue efforts, Li succumbed to his injuries that night. The incident has sparked outrage, particularly in light of several recent stabbing incidents and the ongoing issue of patient-doctor violence, leading many netizens to call for improved security measures in hospitals. Tributes to Dr. Li Sheng online describe him as a man fully dedicated to his work and patients. China’s National Health Commission condemned the attack, stating there is zero tolerance for any form of violence against medical personnel.

JULY 20

🌉 Collapsed Bridge | After heavy rain and flash floods, a highway bridge that had been in use for less than six years in Shangluo, Shaanxi Province, collapsed on July 19th, causing 25 vehicles to fall into the river. While rescue efforts were still underway, the incident has resulted in 12 known deaths and 31 missing. The past weekend, two missing vehicles were found downstream, 4 kilometers from the collapse site. More than 700 professionals from various emergency services, along with over 1,500 local officials and residents, have been mobilized for search and rescue operations.

JULY 17

🔥🚒 Shopping Mall Fire | Videos of a terrible fire at the 14-story Jiuding Department Store in Zigong, Sichuan, spread on Chinese social media on Wednesday night. Initially, the death toll stood at 8, but it later emerged that at least 16 people lost their lives in the flames despite extensive rescue efforts by firefighters. Thirty-nine people were hospitalized. The fire, now known as the “7·17 major fire accident” (“7·17重大火灾事故”), is suspected to be linked to ongoing construction work.

JULY 21

🏅🧳 Olympic Suitcase Fever | Just a few days before the start of the Olympic Games in Paris, and the Olympic fever is noticeable on Chinese social media. Chinese state media have issued phone wallpaper featuring Olympic athletes. However, what recently attracted the most attention are the suitcases used by Chinese athletes traveling to Paris. These suitcases, called “Ying Yong” (英俑), were designed exclusively for the Chinese sports delegation by a company in Hangzhou. The design is themed around the Terracotta Warriors, using red and black and featuring other details inspired by the Terracotta Army.

JULY 22

🏫 Professor Mi | A story about renowned Chinese professor Wang Guiyan (王贵元) has been blowing up on Chinese social media after he was accused of sexual misconduct by a former female doctoral student. She made these allegations through an online video against the professor, who also served as the Party Secretary and Vice Dean of the School of Liberal Arts at Renmin University of China. On July 22, the university responded to the allegations and stated that their investigations found them to be true. As a result, Wang has been expelled from the Party, his professorship has been revoked, his qualification as a graduate supervisor has been canceled, he has been removed from his teaching position at Renmin University, and his employment has been terminated.🔚

What’s Noteworthy

A mother who lost her child while shopping in a mall in Shiyan, Hubei, went to extreme measures to get her child back as soon as possible. On July 19, the panicked woman triggered the mall alarm by smashing the displays at a jewelry store with a fire extinguisher. This caused the mall to shut all its doors and prompted a police squad to arrive within minutes. A viral video of the incident showed the mother shouting for help as she broke glass displays. The child was soon located.

In the past, there have been various stories about children being kidnapped and having their appearances changed quickly, making it much more challenging to find them. One such story from 2018 showed the speed at which human traffickers work: a 5-year-old girl went missing from a local playground at 14:41, and it later became clear that the little girl, taken away in a minivan with a middle-aged woman and another child, departed her city by train just fifteen minutes later. She got off at a station some 60 miles away with changed clothes and a shaved head (read here).

Although the mother may have thought she did the right thing by smashing the displays to get help to locate her child as soon as possible, she is also receiving a lot of criticism online. Commenters argue that the woman should have never lost sight of her child in the first place, let alone vandalized mall property. The jewelry store also had nothing to do with the child going missing. The local police stated that the woman’s actions would be handled according to public security regulations, so she can expect to pay a fine and compensation to the store.

Meanwhile, there are also people who sympathize with the mother, as they don’t want to imagine what could have happened to the child if standard, slower procedures were followed. However, state media outlets warn others not to take the woman as an example.

What’s Popular

She was known as the heroine and villain of Wuxia movies, the queen of the swords, and a martial arts diva. Hong Kong actress Cheng Pei-pei (郑佩佩) trended all day on Chinese social media after news broke that she had died at the age of 78.

The Shanghai-born Cheng had a background in ballet and modern dance—skills she incorporated into the fight choreographies of the martial arts films she made for the Shaw Brothers in the 1960s and 70s. She later moved to the United States. Cheng gained international fame when she starred as Jade Fox in Ang Lee’s “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” in 2000. Cheng suffered from Corticobasal degeneration (CBD), which shares some similarities with Parkinson’s disease.

On social media, Cheng is remembered not only by other actors and celebrities but also by many regular netizens who see her passing as a major loss to the Chinese film industry. (To read more about the Shaw Brothers & Chinese cinema, check our article here.)

What’s Memorable

For this pick from the archive, and in the context of the future being here, we revisit a 2023 article about Chinese state media introducing a virtual news anchor. While the first virtual presenter was introduced in 2019, People’s Daily introduced Ren Xiaorong (任小融) as a virtual presenter/news anchor in 2023. Although virtual news presenters are not yet the norm, this is a trend that is still developing. For example, this week, China’s Military News Agency also launched their virtual anchor to improve communication efficiency.

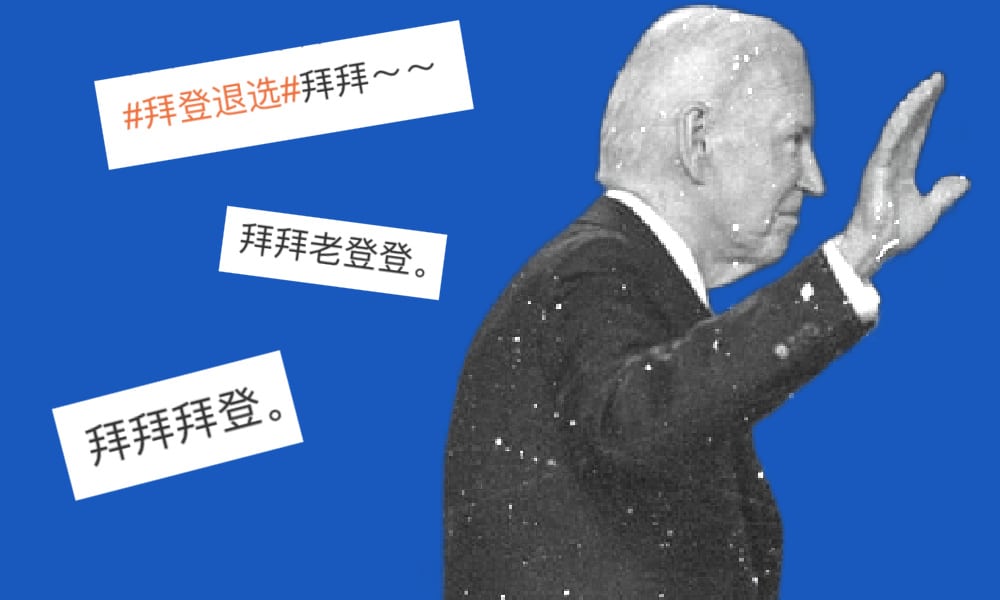

Weibo Word of the Week

Bye Bye Biden | Our Weibo phrase of the week is Bye Bye Biden (bài bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登).

As news of Biden dropping out of the presidential race went viral on Weibo early Monday local time, it’s time to reflect on some of the popular nicknames and phrases given to US President Joe Biden on Chinese social media.

🔹 Biden in Chinese: Bàidēng 拜登

Biden in Chinese is generally written pronounced and written as Bàidēng 拜登. Although the character 拜 (bài) means “to pay respect, to worship” and 登 (dēng) means “to ascend, to climb,” they’re used here primarily for their phonetic similarity. The characters chosen are neutral to avoid any negative implications in the official translation of Biden’s name.

Why are non-Chinese names translated into Chinese at all? With English and Chinese being vastly different languages with entirely different phonetics and scripts, most Chinese people find it difficult to pronounce a foreign name written in English. Writing foreign names in Chinese not only standardizes them but also makes pronunciation and memorization easier for Chinese speakers.

🔹 Bye Biden: Bài Bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登

Because Biden is Bàidēng, and the Chinese for ‘bye bye’ is written as bài bài 拜拜, some netizens quickly created the wordplay “bài bài Bàidēng” 拜拜拜登 (“bye bye Biden”) upon hearing that Biden would not seek reelection. Try saying it out loud—it almost sounds like you’re stammering.

🔹 Old Joe: Lǎo Dēng Dēng 老登登

Another common farewell greeting to Biden seen online is “bài bài lǎo dēng dēng” 拜拜老登登, which sounds cute due to the repetition of sounds.

“Old Biden” or “lǎo dēng dēng” 老登登 is a common online nickname for Biden in Chinese. The reduplication of the 登 (dēng) makes it sound playful and affectionate, while the “old” prefix is commonly used when referring to someone older. It’s similar to calling someone “Old Joe” in English.

🔹 Biden Variations: 拜灯, 白等, 败蹬

Let’s look at some other ways Biden is nicknamed online:

Besides the official way of writing Biden with the 拜登 Bàidēng characters, there are also other variations:

拜灯: bài dēng

白等: bái děng

败蹬: bài dèng

These alternative ways of writing Biden’s name are not neutral. Although the first variation is not necessarily negative (using the formal Biden 拜 bài character but with ‘Light’ 灯 dēng instead of the other 登 ‘dēng’), the other two variations are usually used in more negative contexts.

In 白等 (bái děng), the first character 白 (bái) means “white,” which can evoke associations with old age due to white hair (白发). The character 等 (děng) means “to wait,” and the combination can imply being old and sluggish.

败蹬 (bài dèng) is typically used by netizens to reflect negative sentiments towards the American president. The characters separately mean 败 (bài): “to be defeated,” “to fail,” and 蹬 (dèng): “to step on,” “to kick.” This would never be used by official media and is also often used by netizens to circumvent censorship around a Biden-related topic.

🔹 Revive the Country Biden: Bài Zhènhuá 拜振华

Then there is 拜振华 Bài Zhènhuá: revive the country Biden

In recent years, Biden has come to be referred to with the Chinese nickname “Revive the Country Biden,” also translatable as ‘Thriving China Biden’. This nickname has circulated online since 2020 and matches one previously given to former President Trump, namely “Build the Country Trump” (Chuān Jiànguó 川建国).

The idea behind these humorous monikers is that both Trump and Biden are seen as benefitting China by doing a poor job in running the United States and dealing with China.

🔹 Sleepy King: Shuì wáng 睡王

Shuì wáng 睡王, Sleepy King, is another common nickname, similar to the English “Sleepy Joe.” During and after the 2020 American presidential elections, there were numerous discussions on Chinese social media about ‘Trump versus Biden.’ Many saw it as a contest between the ‘King of Knowing’ (懂王) and the ‘Sleepy King’ (睡王).

These nicknames were attributed to Trump, who frequently boasted about his unparalleled understanding of various matters, and Biden, who gained notoriety for being older and tired. Viral videos, some manipulated, showed him nodding off or seemingly disoriented. The name ‘Sleepy King’ then stuck.

🔹 Grandpa Biden: Bài Yéyé 拜爷爷

Throughout the years, Biden has also been nicknamed Bài yéyé 拜爷爷, “Grandpa Biden.” This is usually more affectionate, though it emphasizes his age—Trump is not much younger than Biden and is not nicknamed ‘Grandpa Trump.’

Another similar nickname is lǎo bái 老白, “Old White,” referring to Biden’s age and white hair. 白 (bái, white) can also be a surname in Chinese. This nickname makes it seem like Biden is an old, familiar friend.

On Weibo, many speculate that American Vice President Kamala Harris will be the new candidate for the Democrats, especially since she’s been endorsed by Biden. Many have little confidence that she can compete against Trump. Her Chinese name is Kǎmǎlā Hālǐsī 卡玛拉·哈里斯, commonly referred to as ‘Harris’ (Hālǐsī).

In light of the latest developments, some netizens jokingly write: “Bye bye Biden, Ha ha ha, Harris.” (Bài bài, Bàidēng. Hā hā hā, Hālǐsī 拜拜,拜登。 哈哈哈,哈里斯). With a new Democratic candidate entering the presidential race, we can expect a fresh batch of creative nicknames to join the mix on Chinese social media.

Want to read more? Also read: Why Trump has Two Different Names in Chinese.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

China Memes & Viral

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Throughout the years, Biden has received many nicknames on Chinese social media.

Published

5 days agoon

July 22, 2024

Our Weibo phrase of the week is Bye Bye Biden (bài bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登). As news of Biden dropping out of the presidential race went viral on Weibo early Monday local time, it’s time to reflect on some of the popular nicknames and phrases given to US President Joe Biden on Chinese social media.

🔹 Biden in Chinese: Bàidēng 拜登

Biden in Chinese is generally written pronounced and written as Bàidēng 拜登. Although the character 拜 (bài) means “to pay respect, to worship” and 登 (dēng) means “to ascend, to climb,” they’re used here primarily for their phonetic similarity. The characters chosen are neutral to avoid any negative implications in the official translation of Biden’s name.

Why are non-Chinese names translated into Chinese at all? With English and Chinese being vastly different languages with entirely different phonetics and scripts, most Chinese people find it difficult to pronounce a foreign name written in English. Writing foreign names in Chinese not only standardizes them but also makes pronunciation and memorization easier for Chinese speakers.

🔹 Bye Biden: Bài Bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登

Because Biden is Bàidēng, and the Chinese for ‘bye bye’ is written as bài bài 拜拜, some netizens quickly created the wordplay “bài bài Bàidēng” 拜拜拜登 (“bye bye Biden”) upon hearing that Biden would not seek reelection. Try saying it out loud—it almost sounds like you’re stammering.

🔹 Old Joe: Lǎo Dēng Dēng 老登登

Another common farewell greeting to Biden seen online is “bài bài lǎo dēng dēng” 拜拜老登登, which sounds cute due to the repetition of sounds.

“Old Biden” or “lǎo dēng dēng” 老登登 is a common online nickname for Biden in Chinese. The reduplication of the 登 (dēng) makes it sound playful and affectionate, while the “old” prefix is commonly used when referring to someone older. It’s similar to calling someone “Old Joe” in English.

🔹 Biden Variations: 拜灯, 白等, 败蹬

Let’s look at some other ways Biden is nicknamed online:

Besides the official way of writing Biden with the 拜登 Bàidēng characters, there are also other variations:

拜灯: bài dēng

白等: bái děng

败蹬: bài dèng

These alternative ways of writing Biden’s name are not neutral. Although the first variation is not necessarily negative (using the formal Biden 拜 bài character but with ‘Light’ 灯 dēng instead of the other 登 ‘dēng’), the other two variations are usually used in more negative contexts.

In 白等 (bái děng), the first character 白 (bái) means “white,” which can evoke associations with old age due to white hair (白发). The character 等 (děng) means “to wait,” and the combination can imply being old and sluggish.

败蹬 (bài dèng) is typically used by netizens to reflect negative sentiments towards the American president. The characters separately mean 败 (bài): “to be defeated,” “to fail,” and 蹬 (dèng): “to step on,” “to kick.” This would never be used by official media and is also often used by netizens to circumvent censorship around a Biden-related topic.

🔹 Revive the Country Biden: Bài Zhènhuá 拜振华

Then there is 拜振华 Bài Zhènhuá: revive the country Biden

In recent years, Biden has come to be referred to with the Chinese nickname “Revive the Country Biden,” also translatable as ‘Thriving China Biden’. This nickname has circulated online since 2020 and matches one previously given to former President Trump, namely “Build the Country Trump” (Chuān Jiànguó 川建国).

The idea behind these humorous monikers is that both Trump and Biden are seen as benefitting China by doing a poor job in running the United States and dealing with China.

🔹 Sleepy King: Shuì wáng 睡王

Shuì wáng 睡王, Sleepy King, is another common nickname, similar to the English “Sleepy Joe.” During and after the 2020 American presidential elections, there were numerous discussions on Chinese social media about ‘Trump versus Biden.’ Many saw it as a contest between the ‘King of Knowing’ (懂王) and the ‘Sleepy King’ (睡王).

These nicknames were attributed to Trump, who frequently boasted about his unparalleled understanding of various matters, and Biden, who gained notoriety for being older and tired. Viral videos, some manipulated, showed him nodding off or seemingly disoriented. The name ‘Sleepy King’ then stuck.

🔹 Grandpa Biden: Bài Yéyé 拜爷爷

Throughout the years, Biden has also been nicknamed Bài yéyé 拜爷爷, “Grandpa Biden.” This is usually more affectionate, though it emphasizes his age—Trump is not much younger than Biden and is not nicknamed ‘Grandpa Trump.’

Another similar nickname is lǎo bái 老白, “Old White,” referring to Biden’s age and white hair. 白 (bái, white) can also be a surname in Chinese. This nickname makes it seem like Biden is an old, familiar friend.

On Weibo, many speculate that American Vice President Kamala Harris will be the new candidate for the Democrats, especially since she’s been endorsed by Biden. Many have little confidence that she can compete against Trump. Her Chinese name is Kǎmǎlā Hālǐsī 卡玛拉·哈里斯, commonly referred to as ‘Harris’ (Hālǐsī).

In light of the latest developments, some netizens jokingly write: “Bye bye Biden, Ha ha ha, Harris.” (Bài bài, Bàidēng. Hā hā hā, Hālǐsī 拜拜,拜登。 哈哈哈,哈里斯). With a new Democratic candidate entering the presidential race, we can expect a fresh batch of creative nicknames to join the mix on Chinese social media.

Want to read more? Also read: Why Trump has Two Different Names in Chinese.

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?