China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Faking Street Photography: Why Staged “Street Snaps” Are All the Rage in China

Staged street photography is the latest “15 minutes of fame” trend on Chinese social media.

Published

5 years agoon

It looks as if they are spontaneously photographed or filmed by one of China’s many street photographers, but it is actually staged. Chinese online influencers – or the companies behind them – are using street photography as part of their social media strategy. And then there are those who are mocking them.

Recently a new trend has popped up on Chinese social media: people posting short videos on their accounts that create the impression that they are being spotted by street fashion photographers. Some look at the camera in a shy way, others turn away, then there are those who smile and cheekily stick out their tongue at the camera.

Although it may appear to be all spontaneous, these people – mostly women – are actually not randomly being caught on camera by one of China’s many street fashion photographers in trendy neighborhoods. They have organized this ‘fashion shoot’ themselves, often showing off their funny poses and special moves, from backward flips to splits, to attract more attention (see example in video embedded below).

These are some examples of the "pretending to be spontaneously spotted by street fashion photographer so gotta do something funny" phenomenon: pic.twitter.com/OUMhGaFG6W

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) 25 juni 2019

In doing so, these self-made models are gaining more fans on their Weibo, Douyin, Xiaohongshu, or WeChat accounts, and are turning their social media apps into their very own stage.

Street Photography in Sanlitun

The real street photography trend has been ongoing in China for years, near trendy areas such as Hangzhou’s Yintai shopping mall, or Chengdu’s Taikoo Li.

One place that is especially known for its many street photographers is Beijing’s see-and-be-seen Sanlitun area, where photographers have since long been gathering around the Apple or Uniqlo stores with their big lens cameras to capture people walking by and their trendy fashion.

A few years ago, Thatsmag featured an article discussing this phenomenon, asking: “Who are these guys and what are they doing with their photos?”

Author Dominique Wong found that many of these people are older men, amateur photographers, who are simply snapping photos of attractive, fashionable, and unique-looking people as their hobby.

But there are also those who are working for street fashion blogs or style magazines such as P1, and are actually making money with their street snaps capturing China’s latest fashion trends.

Image by 新浪博客

People featured in these street snaps can sometimes go viral and become internet celebrities (网红). One of China’s most famous examples of a street photographed internet celebrity is “Brother Sharp.”

‘Brother Sharp’ became an online hit in 2009 (image via Chinasmack).

It’s been ten years since “Brother Sharp” (犀利哥), a homeless man from Ningbo, became an online hit in China for his fashionable and handsome appearance, after his street snap went trending on the Chinese internet.

Staged Street Scenes

But what if nobody’s snapping your pics and you want to go viral with your “Oh, I am being spotted by street fashion photographers” video? By setting up their own “street snap” shoots, online influencers take matters into their own hands.

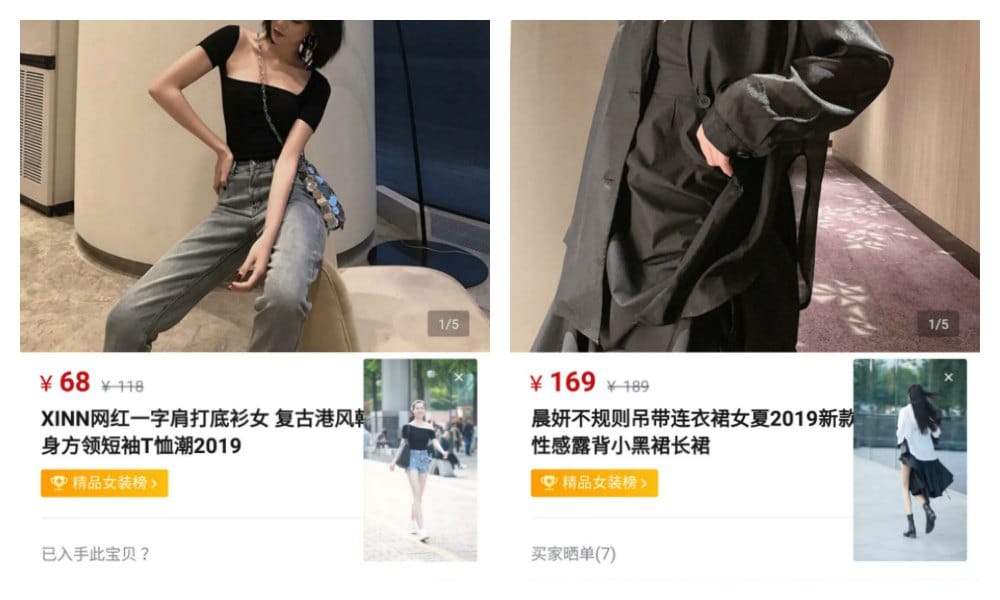

It is not just individuals who are setting up these shoots; there are also companies and brands that do so in order to make their (fashion) products more famous. According to People’s Daily, in Hangzhou alone, there are over 200 photographers for such “street snaps” and hundreds of thousands of models for such “performances.”

The photographers can, supposedly, earn about 20,000 to 30,000 yuan ($2,890-$4,335) per day and the models are well paid.

In this way, the “street snap performance” phenomenon is somewhat similar to another trend that especially became apparent in China around 2015-2016, namely that of ‘bystander videos’ capturing a public scene. Although these videos seem to be real, there are actually staged.

One such example happened in 2017 when a video went viral of a young woman being scolded on a Beijing subway for wearing a revealing cosplay outfit.

The story attracted much attention on social media at the time, with many netizens siding with the young woman and praising her for responding coolly although the woman was attacking her. Later, the whole scene turned out to be staged with the purpose of generating more attention for the ad of a “cool” food delivery platform behind the older lady.

In 2015, photos of a ‘romantic proposal’ made its rounds on social media when a young man asked his pregnant girlfriend to marry him using over 50 packs of diapers in the shape of a giant heart. One bag of diapers carried a diamond ring inside. It was later said the scene was sponsored by Libero Diapers.

Wanghong Economy

Both the latest street snap trend and the staged video trend are all part of China’s so-called “Wanghong economy.” Wǎnghóng (网红) is the Chinese term for internet celebrities, KOL (Key Opinion Leader) or ‘influencer.’ Influencer marketing is hot and booming in China: in 2018, the industry was estimated to be worth some $17.16 billion.

Being a wanghong is lucrative business: the more views, clicks, and fans one has, the more profit they can make through e-commerce and online advertising.

Using Chinese KOLs to boost brands can be an attractive option for advertisers, since their social media accounts have a huge fanbase. Prices vary on the amount of fans the ‘influencer’ has. In 2015, for example, the Chinese stylist Xiao P already charged RMB 76,000 ($11,060) for a one-time product mention on his Weibo account (36 million fans).

According to the “KOL budget Calculator” by marketing platform PARKLU, a single sponsored post on the Weibo account of a famous influencer will cost around RMB 60,000 ($8730).

The current staged street snap hype is interesting for various online media businesses in multiple ways. On short video app Douyin, for example, the hugely popular street snap videos come with a link that allows app users to purchase the exact same outfits as the girls in the videos.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, an online survey by Tencent found that 54% of college-age respondents had the ambition to become an “online celebrity.”

Making Non-Fashion Fashion: The Farm Field as a Catwalk

Although becoming an actual online celebrity used to be a far-fetched dream for many Chinese netizens, the latest staged-street-snap trend creates the possibility for people to experience their “15 minutes of fame” online.

Just as in previous online trends such as the Flaunt Your Wealth Challenge or A4 Waist Challenge, you see that many people soon participate in them, and that they are then followed by an “anti-movement” of people making fun of the trend or using it to promote a different social point-of-view.

The 2018 “Flaunt Your Wealth” challenge, for example, in which Chinese influencers shared pictures of themselves falling out of their cars with their expensive possessions all around them, was followed by an Anti-Flaunt Your Wealth movement, in which ordinary people mocked the challenge by showing themselves on the floor with their diplomas, military credentials, painting tools, or study books around them.

In case of the (staged) “Fashion Street Photography” movement, that now has over 103 million views on Weibo (#全国时尚街拍大赏# and #街拍艺术行为大赏#), you can also see that many people have started to mock it.

“I find [this trend] so embarrassing that I want to toss my phone away, yet I can’t help but watch it,” one Weibo user (@十一点半关手机) writes, with others agreeing, saying: “This is all so awkward, it just makes my skin crawl.”

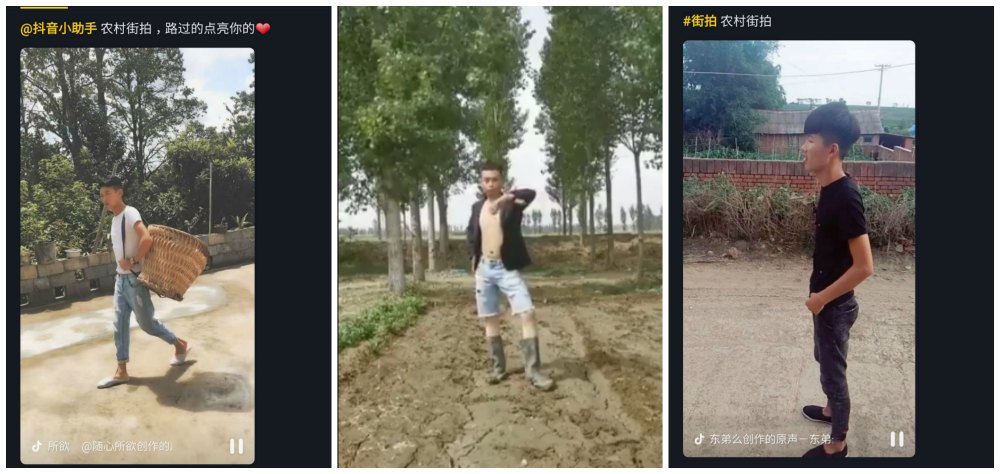

The anti-trend answer to the staged street shoot hype now is that people are also pretending to be doing such a street snap, but ridiculing it by making over-the-top movements, doing it in ‘uncool’ places, wearing basic clothing, or setting up a funny situation (see embedded tweet below).

And then this is other example (there are many) of people mocking this pretending-to-be-spotted-by-street-photographers trend pic.twitter.com/2WBP3F326l

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) 25 juni 2019

Some of these short videos show ‘models’ walking in a rural area, pretending to be photographed by a ‘street fashion photographer’ – it’s an anti-trend that’s become a trend in itself (see videos in embedded tweets below).

There's a recent Chinese social media trend of people mocking the wannabe cool Sanlitun rich kids who are walking the streets like it's their catwalk while pretending to be spotted by street photographers. It's always the anti-cool people who are actually the coolest..👇👏 pic.twitter.com/LnEOEdyzRE

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) 24 juni 2019

Although this ‘anti-trend’ is meant in a mocking way, it is sometimes also a form of self-expression for young people for whom the Sanlitun-wannabe-models life is an extravagant and sometimes unattainable one.

More: pic.twitter.com/WpcDepTcYe

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) 24 juni 2019

They don’t need trendy streets and Chanel bags to pretend to be models: even the farm field can be their catwalk.

In the end, the anti-trend “models” on Chinese social media are arguably much cooler than the influencers pretending to be photographed. Not only do they convey a sense of authenticity, they also have something else that matters the most in order to be truly cool and attractive: a sense of humor.

Also read: Beijing Close-Up: Photographer Tom Selmon Crosses the Borders of Gender in China

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy.

Published

3 days agoon

May 3, 2024

It seemed like such a good idea. For this year’s World Book Day, Chinese tea brand LELECHA (乐乐茶) put a spotlight on Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881-1936), one of the most celebrated Chinese authors the 20th century and turned him into the the ‘brand ambassador’ of their special new “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙) milk tea.

LELECHA is a Chinese chain specializing in new-style tea beverages, including bubble tea and fruit tea. It debuted in Shanghai in 2016, and since then, it has expanded rapidly, opening dozens of new stores not only in Shanghai but also in other major cities across China.

Starting on April 23, not only did the LELECHA ‘Smoky Oolong” paper cups feature Lu Xun’s portrait, but also other promotional materials by LELECHA, such as menus and paper bags, accompanied by the slogan: “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” (“老烟腔,新青年”). The marketing campaign was a joint collaboration between LELECHA and publishing house Yilin Press.

Lu Xun featured on LELECHA products, image via Netease.

The slogan “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” is a play on the Chinese magazine ‘New Youth’ or ‘La Jeunesse’ (新青年), the influential literary magazine in which Lu’s famous short story, “Diary of a Madman,” was published in 1918.

The design of the tea featuring Lu Xun’s image, its colors, and painting style also pay homage to the era in which Lu Xun rose to prominence.

Lu Xun (pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a leading figure within China’s May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1915-24) is also referred to as the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance. It was the cultural revolution brought about by the political demonstrations on the fourth of May 1919 when citizens and students in Beijing paraded the streets to protest decisions made at the post-World War I Versailles Conference and called for the destruction of traditional culture[1].

In this historical context, Lu Xun emerged as a significant cultural figure, renowned for his critical and enlightened perspectives on Chinese society.

To this day, Lu Xun remains a highly respected figure. In the post-Mao era, some critics felt that Lu Xun was actually revered a bit too much, and called for efforts to ‘demystify’ him. In 1979, for example, writer Mao Dun called for a halt to the movement to turn Lu Xun into “a god-like figure”[2].

Perhaps LELECHA’s marketing team figured they could not go wrong by creating a milk tea product around China’s beloved Lu Xun. But for various reasons, the marketing campaign backfired, landing LELECHA in hot water. The topic went trending on Chinese social media, where many criticized the tea company.

Commodification of ‘Marxist’ Lu Xun

The first issue with LELECHA’s Lu Xun campaign is a legal one. It seems the tea chain used Lu Xun’s portrait without permission. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s great-grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation, quickly demanded an end to the unauthorized use of Lu Xun’s image on tea cups and other merchandise. He even hired a law firm to take legal action against the campaign.

Others noted that the image of Lu Xun that was used by LELECHA resembled a famous painting of Lu Xun by Yang Zhiguang (杨之光), potentially also infringing on Yang’s copyright.

But there are more reasons why people online are upset about the Lu Xun x LELECHA marketing campaign. One is how the use of the word “smoky” is seen as disrespectful towards Lu Xun. Lu Xun was known for his heavy smoking, which ultimately contributed to his early death.

It’s also ironic that Lu Xun, widely seen as a Marxist, is being used as a ‘brand ambassador’ for a commercial tea brand. This exploits Lu Xun’s image for profit, turning his legacy into a commodity with the ‘smoky oolong’ tea and related merchandise.

“Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you in an article. ”

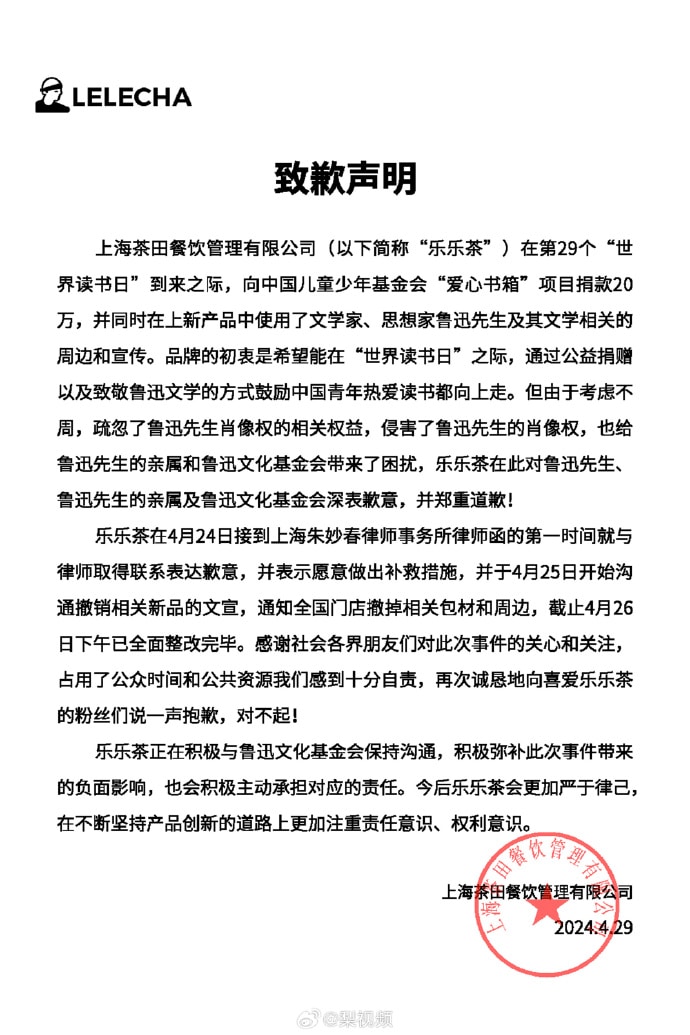

On April 29, LELECHA finally issued an apology to Lu Xun’s relatives and the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation for neglecting the legal aspects of their marketing campaign. They claimed it was meant to promote reading among China’s youth. All Lu Xun materials have now been removed from LELECHA’s stores.

Statement by LELECHA.

On Chinese social media, where the hot tea became a hot potato, opinions on the issue are divided. While many netizens think it is unacceptable to infringe on Lu Xun’s portrait rights like that, there are others who appreciate the merchandise.

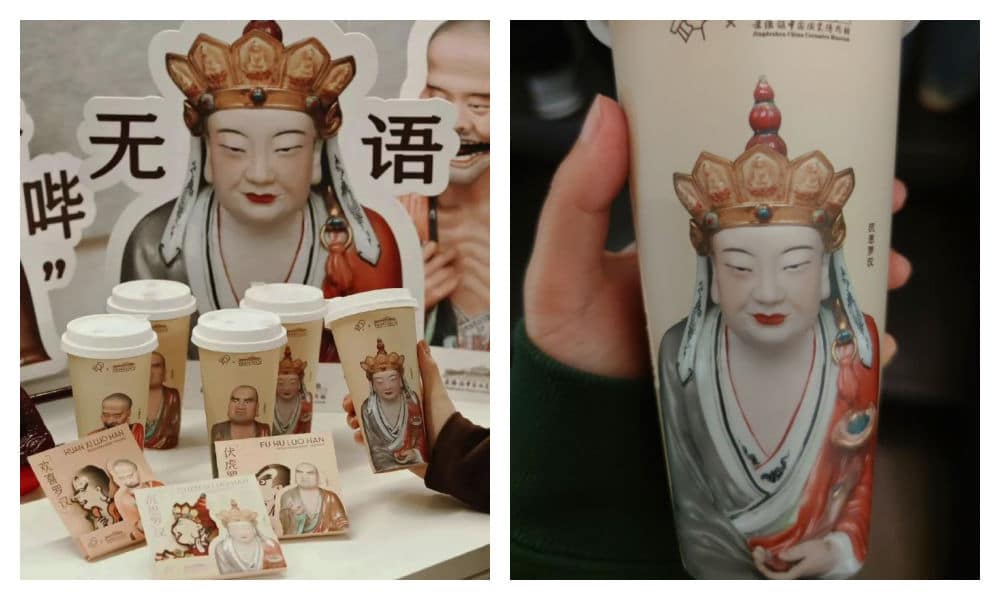

The LELECHA controversy is similar to another issue that went trending in late 2023, when the well-known Chinese tea chain HeyTea (喜茶) collaborated with the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum to release a special ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ (佛喜) latte tea series adorned with Buddha images on the cups, along with other merchandise such as stickers and magnets. The series featured three customized “Buddha’s Happiness” cups modeled on the “Speechless Bodhisattva” (无语菩萨), which soon became popular among netizens.

The HeyTea Buddha latte series, including merchandise, was pulled from shelves just three days after its launch.

However, the ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ success came to an abrupt halt when the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Shenzhen intervened, citing regulations that prohibit commercial promotion of religion. HeyTea wasted no time challenging the objections made by the Bureau and promptly removed the tea series and all related merchandise from its stores, just three days after its initial launch.

Following the Happy Buddha and Lu Xun milk tea controversies, Chinese tea brands are bound to be more careful in the future when it comes to their collaborative marketing campaigns and whether or not they’re crossing any boundaries.

Some people couldn’t care less if they don’t launch another campaign at all. One Weibo user wrote: “Every day there’s a new collaboration here, another one there, but I’d just prefer a simple cup of tea.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Schoppa, Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia UP, 159.

[2]Zhong, Xueping. 2010. “Who Is Afraid Of Lu Xun? The Politics Of ‘Debates About Lu Xun’ (鲁迅论争lu Xun Lun Zheng) And The Question Of His Legacy In Post-Revolution China.” In Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China, 257–284, 262.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Who’s gonna buy this Zara dress in China? “I’m afraid that someone will say I stole the apron from Haidilao.”

Published

2 weeks agoon

April 19, 2024

A short dress sold by Zara has gone viral in China for looking like the aprons used by the popular Chinese hotpot chain Haidilao.

“I really thought it was a Zara x Haidialo collab,” some customers commented. Others also agree that the first thing they thought about when seeing the Zara dress was the Haidilao apron.

The “original” vs the Zara dress.

The dress has become a popular topic on Xiaohongshu and other social media, where some images show the dress with the Haidilao logo photoshopped on it to emphasize the similarity.

One post on Xiaohongshu discussing the dress, with the caption “Curious about the inspiration behind Zara’s design,” garnered over 28,000 replies.

Haidilao, with its numerous restaurants across China, is renowned for its hospitality and exceptional customer service. Anyone who has ever dined at their restaurants is familiar with the Haidilao apron provided to diners for protecting their clothes from food or oil stains while enjoying hotpot.

These aprons are meant for use during the meal and should be returned to the staff afterward, rather than taken home.

The Haidilao apron.

However, many people who have dined at Haidilao may have encountered the following scenario: after indulging in drinks and hotpot, they realize they are still wearing a Haidilao apron upon leaving the restaurant. Consequently, many hotpot enthusiasts may have an ‘accidental’ Haidilao apron tucked away at home somewhere.

This only adds to the humor of the latest Zara dress looking like the apron. The similarity between the Zara dress and the Haidilao apron is actually so striking, that some people are afraid to be accused of being a thief if they would wear it.

One Weibo commenter wrote: “The most confusing item of this season from Zara has come out. It’s like a Zara x Haidilao collaboration apron… This… I can’t wear it: I’m afraid that someone will say I stole the apron from Haidilao.”

Funnily enough, the Haidilao apron similarity seems to have set off a trend of girls trying on the Zara dress and posting photos of themselves wearing it.

It’s doubtful that they’re actually purchasing the dress. Although some commenters say the dress is not bad, most people associate it too closely with the Haidilao brand: it just makes them hungry for hotpot.

By Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

The Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight2 months ago

China Insight2 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 weeks ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 weeks ago“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

-

China Media2 months ago

China Media2 months agoParty Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

Boboy

June 29, 2019 at 8:32 pm

I have a term for people who mocked others “green face”.