China Arts & Entertainment

Watching ‘Chunwan’ 2023: Liveblog CMG Spring Festival Gala by What’s on Weibo

Culture meets commerce, Party propaganda meets pop culture, it’s time for the annual Spring Festival Gala! Watch it with What’s on Weibo.

Published

2 years agoon

As we bid the Year of the Tiger farewell, and welcome the Year of the Rabbit, it is time for the annual CMG Spring Festival show. Watch the Gala together with What’s on Weibo here and follow our liveblog to keep up with what’s happening on screen and the latest on social media.

It is that time of the year again! It is time for the CMG Spring Festival Gala, better known as Chunwan (春晚), one of the world’s most-watched live televised events. Lasting a total of four hours, from 8pm to 1am Beijing time, the Chunwan is annually broadcasted since 1983 and has become a part of the Chinese New Year’s Eve.

The show usually consists of some 30-40 different acts. Although there was a time when the Gala was mostly considered corny and old-fashioned by most young people, the show has now also become ingrained in China’s social media environment. Besides traditionally being broadcasted via CCTV, it can now also be live-streamed through social apps such as WeChat, TikTok, and Kuaishou. This has also helped to boost viewership. The 2021 Gala reached a record 1.14 billion viewers around the globe, and in 2022, another record was broken after some 1.29 billion viewers tuned in at home and abroad.

But while viewer ratings of the Gala in the 21st century have skyrocketed, so has the critique on the show – which seems to be growing year on year. According to many viewers, the spectacle generally is often “way too political” with its display of communist nostalgia and nationalistic songs. This has also led to an increase in censorship. Last year, Weibo issued an indirect warning to netizens criticizing the festive annual Chinese New Year Galas by suspending 21 Weibo users spreading “negativity” regarding broadcasted festival programs and their performances. A few years earlier, Weibo even shut down entire comment sections.

Nevertheless, complaining about the show is part of the tradition now, with the sentence “there will never be a worse, just worse than last year” (中央春晚,没有最烂,只有更烂) always showing up in comment sections. At the same time, many viewers and fans are also looking forward to seeing some of their favorite idols and performers appear on the show.

You might also know the Festival as the ‘CCTV Gala,’ but since 2020, it was rebranded to CMG Gala. CMG stands for China Media Group, which is the predominant state broadcaster in China and was founded in 2018 as a fusion of, among others, CCTV (China Central Television), CNR (China National Radio), and CRI (China Radio International).

CMG is under the direct control of the Central Propaganda Department of the Chinese Communist Party, and the show is an important moment for the Party to communicate its official ideology, highlight traditional culture, and showcase the nation’s top performers. Although the CCTV Gala is also a commercial event, it is still highly political and mixes official propaganda with entertainment.

Since recent years, it has also become a platform to showcase China’s innovative digital technologies. In 2015 the show first featured the exchange of virtual hongbao, red envelopes with money, which WeChat users could obtain while shaking their phones during specific moments in the show. Such marketing strategies have drawn in much younger viewer audiences than before. In 2021, the Gala explicitly presented itself as a “tech innovation event” by using 8K ultra high-tech definition video and AI+VR studio technologies and super high definition cloud communication technology to coordinate performances on stage.

This year, official media also present the event as a “technological innovation” show, which makes extensive use of new technologies such as 5G/4K/8K, AI, VR, and XR to promote China’s digital innovation developments.

The Gala will be broadcast on TV and will be live-streamed via various channels on January 21st, 20.00 pm China Standard Time. So turn on your TV and tune into CCTV or watch on YouTube, or head to the CCTV website. We have also embedded the live stream on this page. We will be live-blogging on this page here and you can scroll & watch at the same time from this page.

This is the 8th time for What’s on Weibo to do a liveblog of the Spring Festival Gala. If you want to know more about the previous editions, we also live-blogged

– 2022: Chunwan 2022: The CMG Spring Festival Gala Liveblog by What’s on Weibo

– 2021: The Chunwan Liveblog: Watching the 2021 CMG Spring Festival Gala

– 2020: CCTV New Year’s Gala 2020

– 2019: The CCTV Spring Festival Gala 2019 Live Blog

– 2018: CCTV Spring Festival Gala 2018 (Live Blog)

– 2017: CCTV New Year’s Gala 2017 Live Blog

– 2016: CCTV’s New Year’s Gala 2016 Liveblog

Liveblog CMG Spring Festival Gala 2023

Underneath here you will see our liveblog being updated. Leave the page open and you’ll see the new posts coming in, there should be a ‘ping’ too with every update.

There will also be some social media updates via Twitter at @manyapan here.

Update: this liveblog is now closed, check below for an overview of the entire show.

——–

The original liveblog was done via a third-party app. The original texts and images are copied below for reference. If there are links to particular segments of the show, they have been added later. The timestamp (in Beijing time) refers to the last moment that post was updated.

——–

What Can We Expect Tonight?

Jan 21 19:41

So, what can we expect for this 41st edition of the Gala? Although the official program list of the show is always leaked days before the event, it is never 100% correct until just one or two days before the actual show. This year, the program was issued on January 20, just a day before the Gala.

This year, the show’s main director is the female director Yu Lei (于蕾). The Gala has had a male chief director for many consecutive years, so it’s nice to see a female director for a change (and “Change” is actually one of the main themes for the night). Yu Lei has an impressive resume with a lot of experience at CCRV, where she is a senior program producer. She’s been closely involved in the production of the Spring Festival Gala since 2013, and also played a role in the production of the G20 performance in Hangzhou and the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics.

Tonight’s show has been completely rehearsed a total of five times before tonight. These rehearsals are recorded and almost nothing ever goes wrong during the live show – perhaps some bad lipsyncing here and there – since the recording is running at the same time so that producers can always switch to a pre-recorded act.

Over the next few hours, we will see a variety of acts, including song and dance, comedy, sketches, opera, martial arts, acrobatics, and more.

● The song “Hello Stranger” (你好,陌生人) will be performed later tonight by Mao Buyi and it was released prior to the show as one of the theme songs about people helping each other out in times of need. The song hints at the difficult times of the past months in which China faced local Covid outbreaks before a major Covid wave hit the country after the ‘zero Covid’ policy was let go in early December of 2022.

● There’s also a Belt and Road Song – a classic Spring Festival Gala element to highlight China’s importance in the world today.

● There will also be a “mini-film” (微电影), which is the first time this genre appears on the show.

● We will see loads of young people tonight. Last year there were also quite some young performers, but there was actually more focus on honoring China’s recognized, elderly performers at the time. We’re gonna see a lot more singers and performers born after the 1990s and 2000s tonight, which suits the Gala’s “New China” theme.

Also: the show’s ending will be different this year as the super famous singer Li Guyi (李谷一) won’t be there. Her absence has gone trending on Weibo, where one related hashtag received 360 million views at time of writing (#李谷一回应缺席春晚#). Li is at the hospital, recovering from Covid.

——–

Tu Yuanyuan, the Mascot

Jan 21 20:02

Ah, what a cute start to the show. The mascot of the show this year is Tu Yuanyuan (兔圆圆). The mascot was created by a special visual arts team, and it took a total of four months to make Tu Yuanyuan come to life through 3D technology.

The rabbit’s chief designer is Mr. Chen Xiangbo, the director of Guan Shanyue Art Museum, and it’s been well-received on Chinese social media.

That is actually quite special at a time when so many rabbits got roasted over their design. Perhaps you read about the Chongqing rabbit lantern getting so much criticism that it was taken down before the New Year even started.

China’s Post blue rabbit stamp was also deemed ugly, and a dedicated mascot was thrown out.

But the Nanning rabbit probably got the most criticism. “You can’t please everyone,” some commenters wrote: “But it is possible to displease everyone.”

——–

Opening Act

Jan 21 20:07

We’ve officially started now! Tonight, so many famous people appear on stage.

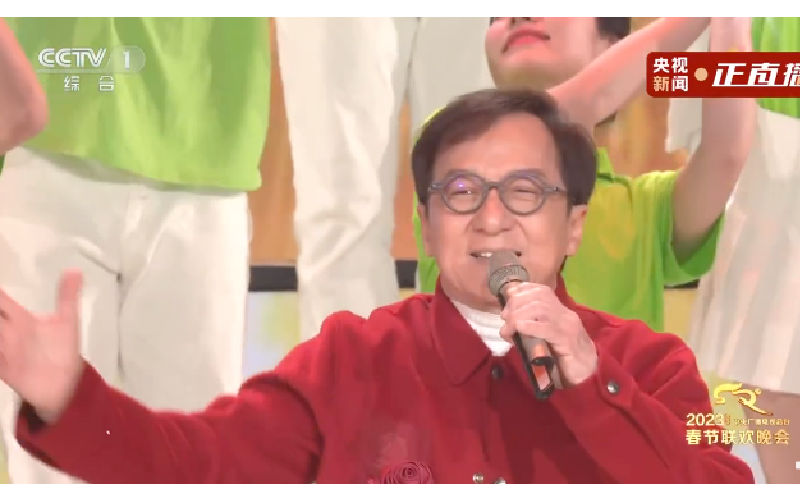

First and foremost, Jackie Chan will return to the stage. Jackie Chan (成龙) has become an annually returning performer at the Spring Festival Gala. The last time he performed at the Gala, in 2021, he sang “Tomorrow Will Be Better” (明天会更好), which was about the epidemic situation. Last year, Jackie Chan wasn’t in the show, so it’s good to see he’s still alive & kicking because it’s become tradition to have him at the Gala.

We will then see some of China’s celebrated Olympic athletes. There’s short track speed skater Wu Dajing (武大靖) who won gold for the 2000m mixed relay at the Winter Olympics in Beijing in 2022; there’s Xu Mengtao (徐梦桃), who won China’s first Olympic gold medal in the women’s freestyle skiing aerials; there’s also Gao Tingyu (高停宇) who won the men’s 500m speed skating gold medal with an Olympic record of 34.32 seconds at the Beijing Winter Olympics (he became China’s first-ever male Olympic gold medalist in speed skating).

But Gu Ailing (Eileen Gu) wasn’t listed, despite being one of the stars of the Beijing Olympics in 2022. Despite her popularity, she also triggered some controversy after the Olympics after some online discussions focused on her alleged privileged position. At the time of the Gala, Gu is competing at the Freestyle Ski World Cup in Calgary.

We will also see a bunch of very famous actors and actresses on stage. We see Qin Hailu (秦海璐), Taiwanese actor Alec Su (苏有朋), Chinese actress Yang Zi (杨紫 aka Andy Yang), actor Sha Yi (沙溢), Wu Lei (吴磊), Zhao Liying (赵丽颖), Bai Yu (白宇), Oho Ou (欧豪), Song Zu’er (宋祖儿), Song Yi (宋轶)Wan Qian (万茜), Wang Baoqiang (王宝强), Rayzha Alimjan (熱依扎), Qin Lan (秦岚) and Josie Ho (祖丝), and many others, accompanied by different choir and dance groups, who are all from various places, from Beijing to Nanjing and beyond.

——–

Tonight’s Hosts

Jan 21 20:08

The line-up of hosts was previously released.

Ren Luyu 任鲁豫 (1978)

Chinese television host from Henan, who has also presented the Gala multiple times (2010, 2016, 2018, 2019, 2021). Familiar face to the show.

Sa Beining 撒贝宁 (1976)

Also known as Benny Sa, Sa presented the Gala in 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016 and in 2022. He is a famous Chinese television host known for his work for CCTV.

Nëghmet Raxman尼格买提 (1983)

Nëghmet is a Chinese television host of Uyghur heritage who also is not a newcomer; he hosted the Gala since 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, and in 2021.

Long Yang 龙洋(1989)

She was the youngest presenter hosting the CCTV Gala in 2021. Born in Hunan’s Chenzhou, she’s been working in Chinese state media for years. As a host, she’s done various big events before, but 2021 was the first time for her to host the CMG Spring Festival Gala.

Ma Fanshu 马凡舒 (1993)

Ma Fanshu was the youngest and newest host in the 2022 Gala. She is a sports program host who has also been called “the most beautiful host of CCTV.”

Wang Jianing 王嘉宁 (1992)

The Beijing-born Wang Jianing, born in Beijing, is a Chinese actress and, unless we’re mistaken, this is the first time she is a host at the Gala. She graduated from the New York Film Academy with a performance and directing major and has since starred in many Chinese television dramas, movies, and TV shows.

——–

“Let’s Eat, Let’s Have Fun”

Jan 21 20:12

This song (“开饭!开FUN!”) has some happy vibes. Uncoincidentally, Da Zhangwei (大张伟) – better known as Wowkie Zhang – also performed a song titled “Happy Vibes” in 2022. Singing with him is the TV star and singer Zhang Ruoyun (张若昀).

On stage with them are four different dance troupes, including the China Post Art Troupe.

Meanwhile, on social media, some wonder if everyone on stage had agreed to wear red without Yang Zi being informed about it.

——–

“Hundred Birds Return to the Nest”

Jan 21 20:14

This song is titled “Homing Birds” (百鸟归巢) and it’s sung by Tan Weiwei (谭维维) who is also known as Sitar Tan. She is a singer from Sichuan who rose to fame when she became a runner-up in the Super Girl talent show.

This is her third appearance on the show, as she also performed at the Spring Festival Gala in both 2016 and in 2022. In 2020, she released a noteworthy album titled 3811 which focused on the struggles women in China are facing, with each of the eleven songs on the album telling the different stories of women from diverse backgrounds.

——–

No More Masks!

Jan 21 20:19

Something we already wondered about: would the audience be wearing masks for this year’s Gala or not? They are not! Last year’s Gala in 2022 was the second year the audience was wearing a face mask. In 2020, when Wuhan was first facing the Covid19 outbreak, the audience was not wearing face masks yet. 2021 was the first year.

By the way, something unrelated; it’s noteworthy that renowned CCTV host Zhu Jun (朱军) still has not returned to the Gala. The presenter was accused of sexually assaulting an intern in 2018 and hasn’t been a host at the Gala since. Although the intern lost the sexual harassment lawsuit against Zhu Jun, he still hasn’t reappeared and it seems he has really lost his spot on the show now.

——–

Time for Some Crosstalk

Jan 21 20:22

This is the first xiangsheng (相声) act or crosstalk act of the night. Xiangsheng is a traditional Chinese comedic performance that involves a dialogue between two performers, using rich language and many puns.

This act is performed by Yue Yunpeng (岳云鹏, 1985), who is particularly known for his xiangsheng performances. He is part of a famous duo together with well-known Beijing-born comedian Sun Yue (孙越1979). They’ve previously also performed together at the Gala in 2020 and 2021.

The participating poker magician is Jian Lunting (简纶廷) from Taiwan.

——–

Theme: “China’s New Era and a Better Life”

Jan 21 20:28

Every year, the Gala has a special theme or a recurring narrative. This year’s theme is not particularly original, but it does make sense in the context of what happened over the past year. After previous themes such as “New China”, “Chinese Dream”, “National Unity”, “Family Affinity”, and “Chinese values, Chinese power,” this 2023 year’s theme is all about “China’s Flourishing New Era” and “A Better Life amid Rapid Changes” (“欣欣向荣的新时代中国,日新月异的更美好生活”).

“China’s New Era and a Better Life” should be seen in the context of China’s reopening, rapid changes over the past months, and the continuance of China’s road to rejuvenation, which was also strongly reiterated during the 20th Party Congress in October 2022. The themes that were highlighted there (read more here) also play an important part during the Gala, such as Chinese-style modernization, building a strong socialist modern country, being united in struggle, and building beautiful China with a focus on green development. We’ll see these themes come up throughout the show.

Another clear theme is homecoming, as this year will be the first time many families can finally reunite since the start of the Covid outbreak (people were previously discouraged from traveling home, doing a ‘staycation’ instead for the new year).

As noted by Andrew Methven @ Slow Chinese, the language and visuals used throughout the show are also a lot about flowers and blossoming, with some of these titles purposely sounding like “growing flowers”, which sounds the same as “China” (种花 / 中华 / 中华民族 / 以花为名). This resonates with the theme of a New China.

——–

“Good Luck Will Come”

Jan 21 20:31

Popsong with traditional influences. On stage, we see Deng Chao (邓超, 1979), who is a Chinese actor, comedian, director, and singer. He is known for his work in multiple box-office hit films such as The Mermaid (2016) and Duckweed (2017). He also appeared as a singer in last year’s Gala, when he performed together with Jackson Yee and Li Yuchun.

Tonight, Deng is on stage with Wang Erni (王二妮, 1985), the famous singer from Shaanxi who had her major breakthrough in 2007 with her Northern Shaanxi folk songs.

——–

Acrobatics (“龙跃神州”)

Jan 21 20:33

Yang Hao (杨浩), Li Yifan (李一凡), and Zhang Haozheng (张浩正) perform in tonight’s fist acrobatics act with, among others, the Cangzhou Acrobatics Troupe.

——–

“Clear waters and green mountains” (“绿水青山”)

Jan 21 20:40

“Clear Waters and Green Mountains” (绿水青山) is the title of this song, which refers to a political slogan on environmental policy formulated by Xi Jinping and is all about emphasizing the harmony between people and nature.

This song is sung by Huang Xiaoyun (黄霄雲, 1998), a singer/actress of Bouyei ethnicity who mostly became known due to the talent show The Voice of China in 2015. Also on stage is Shan Yichun (单依纯), who was the Voice of China winner in 2020.

Song Yi (宋轶, 1989) and Song Zu’er (宋祖儿, 1998) are both well-known actresses, mostly known for starring in various hit TV dramas.

This performance includes Chinese traditional Huangmei opera, one of the five major opera genres in China, by performers Pan Ningjing (潘柠静) and Zhang Xiaowei (张小威).

See a link to this performance here.

——–

Zhang Ruoyun eating the chicken

Jan 21 20:44

During an earlier performance (the xiangsheng one), actor Zhang Ruoyun (张若昀) got the roasted chicken that magically appeared during the magic trick performed by magician Jian Lunting. The fact that he actually ATE the chicken while sitting in the audience is something that is causing some giggles on social media.

Maybe he was just really hungry!

——–

Xiaopin: “First Look Photo Studio”

Jan 21 20:57

This is the first sketch comedy or short play of the night, called xiaopin 小品 in Chinese. Traditionally, the xiaopin is both the best-received and most-condemned type of performance of the Gala for evoking laughter among the audiences or triggering controversies for reinforcing (gender) stereotypes.

In 2017, for example, the sketch “Long Last Love” was about a woman who wanted to divorce her husband because she was not able to conceive children and wanted her husband to move on to another wife. The show was criticized for depicting women as “breeding machines” and viewers later demanded an apology from CCTV via social media.

Xiaopin sketches are usually not so deep though – they’re filled with puns, funny lines, and plot twists to entertain the viewers.

In this sketch, titled “First Look Photo Studio” (初见照相馆) we see Yu Zhen (于震), Sun Xi (孙茜), Bai Yufan (白宇帆), Zhang Jianing (张佳宁), Ma Xudong (马旭东), Lu Tengfei (吕腾飞), Li Hongjia (李红佳).

It’s about a couple who lost their marriage certificate and came to make new photos. Two couples meet in the photo studio, showing the contrast between the older and the younger generation. The younger couple still has some natural innocence and cuteness about them as a couple (all dressed in matching outfits), while the older couple has a lot of complaints about their marriage. In the end, the older couple also turns out to be very loving and encourage the younger generation to pull through, even if times are hard. The message of this sketch seems to be: get married, stay married – an important message at a time of falling marriage and birth rates!?

——–

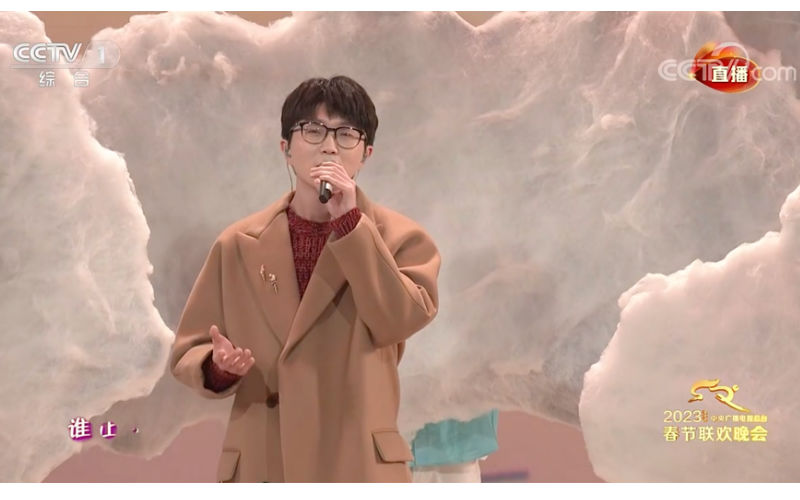

“Hello Stranger”

Jan 21 21:01

“Hello Stranger” (“你好, 陌生人”) is a song that was released prior to the Gala by CMG as one of the theme songs for the night. Performed by the 28-year-old Chinese singer-songwriter Mao Buyi (毛不易), the song is all about helping each other and it already received some praise on Weibo prior to the show (hashtag: #毛不易春晚唱你好陌生人#).

Mao Buyi rose to fame in 2017 thanks to the all-male singing competition “The Coming One” show. At the time, he was a 23-year-old nursing graduate. As previously described by Sixth Tone, Mao stood out in the show due to his “sheer normality.”

We also spotted the first creepy rabbit of the night, although online opinions vary on this.

Another rabbit that is attracting attention is actually very cute; it’s the one on the jacket of Ren Luyu, one of the hosts.

——–

Martial Arts Spectacle!

Jan 21 21:06

This spectacular martial arts show is performed by Vincent Zhao Wenzhuo, the Shaolin Martial Arts Group, and the Shaolin Tagou Martial Arts School from Henan.

Vincent Zhao Wenzhuo (1972) is a famous Chinese actor and martial artist, best known for starring in the Once Upon a Time in China action film and television series.

——–

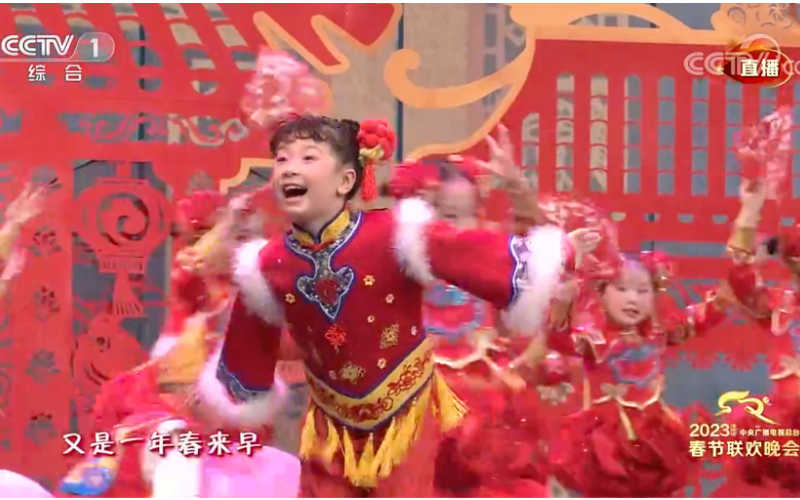

Me and My Grandpa

Jan 21 21:11

We just saw the first public service ad of the night; these are short videos in between the show containing a propaganda message. The title of this video was “Village Night” (“村晚”), a word play on the Chunwan, the Spring Festival Gala Night, as it sounds similar.

This next act is a performance for the kids, titled “Me and my Granddad Walk on Stilts” (我和爷爷踩高跷). There’s a special kid’s show every year, and they’re often quite popular for being so cute.

——–

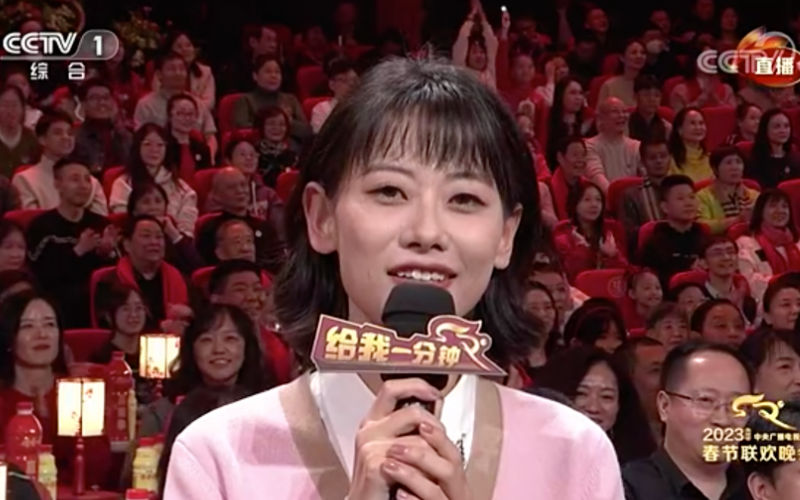

“Give Me A Minute”

Jan 21 21:16

This is a stand-up comedy-like part of the show titled “Give Me a Minute” featuring Zhao Xiaohui (赵晓卉), Qiu Rui (邱 瑞), He Yanzhi (何广智), and Xu Zhisheng (徐志胜).

Last year, a similar performance (which came as a new kind of performance genre) received a lot of criticism, as people do not find the format of the ‘talk show + singing’ suitable for the Chunwan.

By the way, did you notice that the rabbit in the background interacts with the content of the show? It is displayed at all times and laughs about jokes and looks around in the audience. It is the first time for the Gala to have such a mascot, and if you see its 3D design and how interactive it is, you can understand why the development project of ‘Tu Yuanyuan’ (the rabbit’s name) took four months in total, involving an entire team!

——–

“Toast to the Past”

Jan 21 21:22

This song, performed by Taiwan singers Chiang Yu-Heng (姜育e) and Alec Su (苏有朋), together with Reno Wang (王铮亮) and Silence Wang (汪苏拢), is meant as a romantic, nostalgic “Toast to the Past” (跟往事干了好几杯).

Silence Wang (Wang Sulong) is an ethnic Manchu, whose first album came out in 2010 when he was 20 years old.

——–

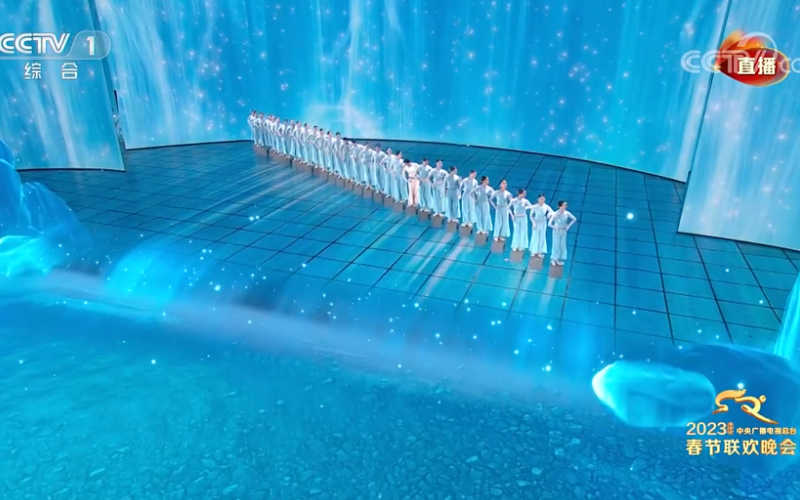

Beautiful Dance

Jan 21 21:29

In this dance performance (碗步桥), we see Shanghai Dance School’s Zhu Jiejing (朱洁静, 1985).

Zhu was selected from a group of 3,000 applicants to attend the Shanghai Dance School at the age of nine. She later rose to fame with her roles in productions such as Farewell My Concubine, and became the vice chairman of the Shanghai Dancers’ Association.

——–

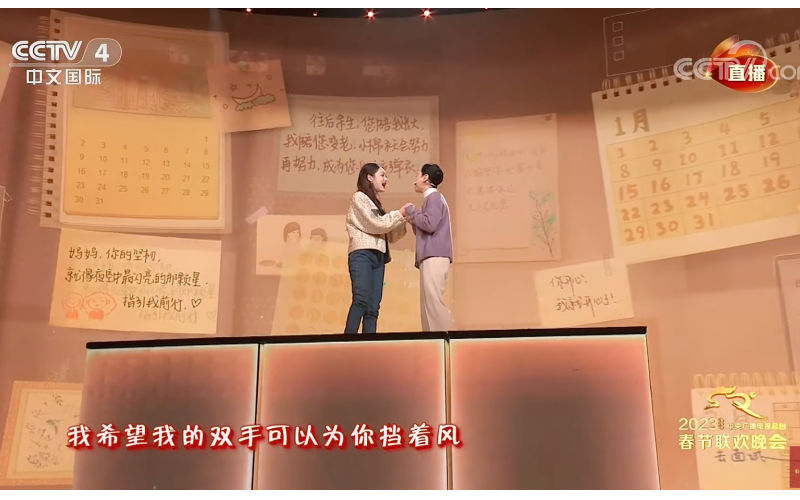

“Mini Film” – “Me and My Chunwan”

Jan 21 21:37

This ‘mini-film’ features some of China’s super famous actors, such as Jacky Wu, Huang Bo, Sandra Ma Sichun, Fan Wei, and others. It is the first time for the Gala to introduce such a film, which is different from the short public service ads that pop up two or three times during the show.

This mini film, titled “Me and my Spring Festival Night” (我和我的春晚) is meant to highlight the personal stories of ordinary people watching the Gala and was inspired by actual letters sent in by viewers. The presenter just mentioned that even in these digital times, people still write letters to the show.

——–

Goodmorning Sunshine

Jan 21 21:43

Multiple people from all kinds of professions and social groups are represented in “Good Morning, Sunshine,” including medical workers.

What is really remarkable is that the topic of the epidemic and Covid have not been explicitly mentioned at all yet. There’s been some hinting at “difficult times” and “change”, but Covid and the many infections throughout the country have not been addressed. This song is an indirect reference to the epidemic situation, singing about sunshine always coming after rainstorms.

——–

“I’m Coming”

Jan 21 21:52

Another xiaopin, a comical skit, this time featuring Chinese celebrity performers Wang Baoqian, Yang Zi, and Wang Ning.

Yang Zi is also known as Andy Yang, and she is a well-known Chinese actress and singer. She was previously named one of the ‘Four Dan Actresses’ (top actresses) of the post-90s Generation.

Wang Baoqiang is also very popular, perhaps also due to his humble background. At the age of 8, the actor left his family to study kung fu and later went to Beijing to play small roles as an actor in film and TV while doing construction jobs on the side. Wang made his big break when major director Feng Xiaogang chose him to play in A World Without Thieves (2003). Wang later became a critically acclaimed actor, known for his roles in films like Blind Shaft (2003) and A Touch of Sin (2013).

——–

Little Brother

Jan 21 22:01

This song, performed by Huang Bo, is about all those delivery drivers across China. It suits the comical sketch that just preceded it, as the message was also to have more understanding for other people in tough jobs like the delivery staff.

The host Nëghmet Raxman 尼格买提 also just mentioned the epidemic for the first time when introducing this song, as he said that especially the ‘kuaidi’ and food delivery drivers have been struggling and working a lot to keep society going in Covid times.

——–

Garden Full of Flowers

Jan 21 22:04

This stunning performance is called “Garden Full of Flowers/”National Colors”(满庭芳·国色) [translated by CCTV as C”ourtyard of Beauty, Colors of A Nation”], performed by Chinese actress Zhao Liying (赵丽颖) and others. It uses a lot of the special technologies (VR, XR) that were already promoted by the show’s directors beforehand.

——–

Forget Your Worries

Jan 21 22:10

After a second public service ad of the night, we’ve already arrived at the 20th performance of the night.

Zhou Shen (周深) is singing this song (“花开忘忧”), with performances by Li Guangfu (李光复) and Sun Guitian (孙桂田). As previously mentioned in another post here, flowers are really a recurring theme throughout the night as they represent blossoming (main theme is “flourishing new China”) and new beginnings.

——–

Treadmill

Jan 21 22:14

Some netizens have noticed how during the performance of the “Little Brother” song, an actual treadmill appeared on stage to make the performers walk. Some people find it funny: Huang Bo didn’t come to the Gala to perform, he came there to work out!

——–

Beautiful Pear Garden (华彩梨园)

Jan 21 22:21

The first major Chinese opera performance of the night! These kinds of performances are generally well-liked among viewers, much more than comical sketches, which many people do not find that funny.

The actors on stage are all of different ages: the youngest performer is only 4 years old!

In this performance, you can also see the use of some cool effects made possible by the show’s integration of new technologies such as 4K/8K, AI, and XR.

——–

How’s this show different from other years thus far?

Jan 21 22:35

There are some ways in which this show is different thus far. Over previous years, the Gala partnered with Tencent, Kuaishou, Baidu, Bytedance, JD, etc to allow various ‘media moments’ during which viewers can ‘catch’ red envelopes. Actually, the Gala became especially linked to social media since it first featured this kind of exchange of ‘hongbao’, red envelopes with money, which is a Chinese New Year’s tradition. In 2015, for the first time, viewers were able to receive virtual ‘hongbao’ as part of a cooperation between CCTV and WeChat. WeChat users shook their phones 11 billion times that night in order to ‘grab’ the money. These kinds of campaigns drew in many more young viewers – the Gala was previously viewed as something for older audiences (– although it still might be, social media has helped get the younger viewers involved, too).This year, we haven’t seen any kind of ‘shake your phone’ or ‘grab hongbao’ media activities.

Another difference is that the show is normally held across several locations besides the main studio in Beijing, which is a great opportunity for other places to boost tourism and attract attention to their region or city. In light of Covid, the Gala was also only held in Beijing’s CCTV studio 1 in 2021 and 2022. Perhaps the choice to again have just one location for the Gala is also related to the current Covid situation. This also still makes the Gala a bit less ‘spectacular’ and festive than the earlier versions before 2020, probably because it would not be appropriate at this time.

——–

Local authorities not doing their job

Jan 21 22:48

The name of the comical skit we just saw was “Hole” or “Pit” (抗), and it was about local authorities not properly doing their job to fix a hole in the street, despite it being dangerous for people.

This skit is among the most well-received ones tonight, as many people recognize the scene as part of everyday realities. The actors in this skit are Shen Teng (沈腾), Ma Li (马丽), Ai Lun (艾伦), Chang Yuan (常远), Song Yuan (宋阳), and Yu Jian (于健).

——–

Mother and Daughter

Jan 21 22:50

This is a really sweet song about the bond between mother and daughter. Perhaps this is the influence of having a female director? Huang Qishan (Susan Huang) is a 54-year-old Chinese musician who has also been referred to as the “number one female voice in Asia.”

The song is also performed by the Beijing-born Curley Gao (希林娜依·高). The 24-year-old singer has a Uighur first name because her mum is from Xinjiang (her dad is Han Chinese from Beijing). Although she is known as ‘Curley’ in English, her actual first name is transcribed as Shirinay (Xilinnayi). She rose to fame due to her participation in the “Sing! China” talent show.

This song is striking a chord among the people in the audience, and a little boy and an older woman were filmed as they got a bit teary-eyed.

——–

High-tech song

Jan 21 22:52

This act, focused on kids, uses new VR + 3D technologies to let the mystic animals of the ancient past meet with Chinese children the present-day.

——–

Future, I’m Coming

Jan 21 22:58

The future is always an important topic during the Gala, and this song is comparable to songs that were featured on previous Gala nights. It’s titled “Future I’m Coming” and it is performed by Ou Hao, Bai Yu, Wei Chen, and Wu Lei. It even includes some rap..

——–

“I Made It to the Hot Search List!”

Jan 21 23:08

This sketch is about a social media video unexpectedly going viral and causing problems between husband and wife as the husband said things he did not mean in order to get more clicks.

One discussion that has come up prior to this show is that the popular Chinese comedian actress Jia Ling is not performing today. She is known for her annual Spring Festival Gala performances together with Zhang Xiaofei.

——–

Everything is going to be ok

Jan 21 23:18

The hosts just addressed Covid for the first time this show. It also looked as if Ren Luyu was tearing up.

The song that follows is a classic pop song performed by a group of artists (Xiao Ke, Sha Yi, Qin Hailu, Hu Xia, Hui Yuanmeng, and Li Guangjie), and they are bringing a positive message about things taking a change for the better.

——–

As Beautiful as Brocade (锦绣)

Jan 21 23:23

This beautiful dance featuring main dancer Li Qian (李倩) and the Beijing Art Troupe is inspired by the Han Dynasty.

See a link to this performance here.

——–

“One Belt, One Beautiful Road Song” (一带繁花一路歌)

Jan 21 23:29

In this most international song of the night, we see a compilation of songs and performers from Indonesia, Greece, Serbia, Egypt Pakistan, New Zealand, Tanzania, Argentina, Kazakhstan, and then the last song, the famous Chinese “Mo Li Hua” [Jasmine Flower] song, is sung by a group of singers from various ‘Belt and Road’ countries.

Lang Lang is on stage playing the piano!

Over the past few years, the Belt and Road Initiative wasn’t really featured very much at the Gala during the closed, Covid era. Now that the borders have reopened, there is room for more international focus again, even if the performers are joining via video.

——–

“My Hometown”

Jan 21 23:37

After the third public service announcement of the night, we’re on to the song “Hometown,” performed by Tibetan singer Alan Dawa Dolma (阿兰·达瓦卓玛), ethnic Mongol singer Daiqing Tana (黛青塔娜), Kashgar singer Air (艾热), Gansu singer Zhang Gasong (张尕怂), and Wu Tong (吴彤) from Liaoning. There’s always a song during the Gala that has different minorities from all over the country. This time, this is it, and they tried to do it a bit different this time by also integrating some modern rock and pop music.

——–

Exemplary Persons

Jan 21 23:40

Like every year, this is the part of the show where some ‘exemplary persons’ get honored for their accomplishments. This special segment recognizes people for their exceptional service and contributions to the Party and the country.

——–

“Youth to the Sun” (青春向太阳)

Jan 21 23:44

Ah, here’s Jackie Chan again after being absent during last year’s performance. Jackie Chan (成龙) has become an annually returning performer at the CCTV Gala. Although his performances are always much-anticipated, they’ve sometimes also been pretty cringe-worthy. In 2017, the song performed by Jackie was simply titled “Nation” and was met with criticism for being overly political. In 2018, the Hong Kong martial artist sang a song that was called “China” and in 2019 he performed ‘My Struggle, My Happiness.’ In 2021 he sang “Tomorrow Will Be Better” (明天会更好) which was about the epidemic situation and that song was actually received very well and made many viewers tear up.

He is now performing a song dedicated to China’s youth, together with Peng Yuchang (1994), Jiang Yiyi (2001), Guo Junchen (1997), Chen Linong (2000, from Taiwan), Yan Mingxi (2005, from Hong Kong) and Josie Ho (1989, from Macao).

——–

A Song for All My Friends

Jan 21 23:46

Sun Nan is here! Sun Nan (孙楠) is a famous Chinese Mandopop singer who performed at the Gala multiple times over the past year, including the iconic 2016 performance where he danced together with 540 robots. In 2022 he was on stage with Tan Weiwei.

This time he is on stage with Hacken Lee (李克勤).

Just before this song started, the host addressed the difficulties so many in China faced over the past year. Although Covid is barely mentioned, the Gala has definitely hinted at the epidemic several times. Instead of some sad songs, the program is mostly filled with songs that are about positivity, hope, friendship, and “better times” – which is also one of the show’s main themes.

——–

Homeland

Jan 21 23:52

We actually thought the main “minority song” was already featured, but “Homeland” (家园) turns out to be the true “minority song” of the night, featuring dancers and singers from various minority groups, holding hands together in unity and singing about love.

——–

Nearing Countdown, Expedition

Jan 21 23:55

It’s almost time for the countdown! First, we are seeing the song “Expedition” (远征) performed by Liao Changyong, Wu Bixia, Wang Kai, and Yisa Yu.

——–

Countdown! Happy New Year!

Jan 21 0:05

Countdown! Happy New Year to you! All the hosts have just expressed their well-wishes to the viewers, wishing everybody blessings for the Year of the Rabbit. The countdown was started with everybody on stage, and there were even some well-wishes from out of space! [Added comment: although we didn’t immediately notice during the show, many social media users later commented that the countdown moment saw some delay and was not exactly times at 0:00.]

“New Year Hopping” (新春蹦蹦) is performed by Phoenix Legend, Chinese rapper Dong Baoshi, and Chinese actress/singer Angel Zhao. Phoenix Legend is a Chinese popular music duo of female vocalist Yangwei Linghua and male rapper Zeng Yi. The duo was also part of the CCTV Gala in 2016 and in 2018.

All the performers are joined on stage by Tu Yuanyuan, the little rabbit that undoubtedly is the star of the 2023 Gala. It danced right there with them.

——–

Last Performances of the Night

Jan 21 0:20

After the comical skit performed by Jin Jing, Zhou Tienan, Yan Peirun (a romantic one about couples), we are now moving on to the “Group Photo” song.

This song is performed by Xu Song aka Vae, an independent musician from Hefei who is super popular on social media.

——–

“To Advance Bravely”

Jan 21 0:22

This is the 38th act of tonight and also the last acrobatics one featuring performers Shi Renqi, Li Songlin, and Yang Jinhao together with the China Acrobatic Group.

——–

Our Field and Dreams in Spring

Jan 21 0:28

The final dance of the night, titled “Our Field” (我们的田野) is a beautiful performance by the Liaoning Ballet.

The performance, all set in golden colors, is about harvesting wheat.

The performance is followed up by “Dreams in Spring.”

“Dreams in Spring” (梦在春天如愿) is performed by Wei Song, Huo Yong, Mo Hong, and Wang Li – among so many young performers this night, they represent the older generation of artists.

——–

Unforgettable Night

Jan 21 0:35

This is a very unusual ending to the Gala. Ever since the 1980s, the last song of the night was “Unforgettable Night” (难忘今宵) sung by Li Guyi (李谷一). As Li is now recovering from Covid at the hospital, all the performers are gathered on stage and sing the song together.

The song was composed in 1984 when CCTV was preparing for its second Spring Festival Gala.

That’s a wrap! Thank you so much for joining, and we wish you a very happy Year of the Rabbit.

By Manya Koetse , with contributions by Miranda Barnes, and Zilan Qian

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

Also Read

China Arts & Entertainment

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

“I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like listening to Alicia Keys.” Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers.

Published

2 months agoon

May 17, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

Besides memes and jokes, Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers on Chinese social media.

In May, while the whole of Europe was gripped by the Eurovision Song Contest frenzy, Chinese audiences were eagerly anticipating the return of their own beloved singing competition, Singer 2024 (@湖南卫视歌手), formerly known as I Am a Singer (我是歌手).

The show, introduced from South Korea’s MBC Television and popular in China since 2013, only features professional singers who have already made a name for themselves.

Rather than watching unknown aspiring singers who are hoping to be discovered in many singing competitions, such as Sing! China, Singer 2024 gives audiences a show filled with professional and often stunning show performances by established names in the entertainment industry.

Since 2013, renowned singers from China and abroad have appeared on the show, including Chinese vocalist Tan Jing (谭晶), British pop singer Jessie J, and the late Hong Kong pop diva Coco Lee. However, no season managed to create as many waves as the 2024 season did, dominating all social media trending topics overnight.

So, what exactly happened?

COMPETING WITH FOREIGNERS

“The difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival”

In early May, the pre-show promotion of Singer 2024 was already buzzing on Chinese social media after a list of featured singers appeared on Weibo, including big names such as American singer-songwriter Bruno Mars, Korean-New Zealand singer Rosé from Blackpink, and Japanese diva LiSA.

Although Singer previously had many foreign singers on the show, this international celebrity lineup still caused a stir.

On the day of the first episode, only two foreign singers were announced to appear on the show: young Moroccan-Canadian singer Faouzia and the Grammy-nominated American singer-songwriter Chanté Moore. The other contestants were all Chinese singers who are already well-known among Chinese audiences. Because many people were unfamiliar with the two foreign singers, they joked that the winner of this season was already set in stone; surely it would be the famous Chinese singer Na Ying (那英), known for her beautiful voice.

However, that first episode surprised everyone as the two foreign singers, Faouzia and Chanté Moore, showed outstanding vocal skills. This not only startled many viewers but also made the Chinese contestants uneasy. Several experienced Chinese singers apparently were so unnerved after watching Faouzia and Chanté Moore’s performance that their voices trembled when singing.

Since the show was broadcast live – without post-production editing or autotune – audiences got to hear the actual vocal capabilities and see performers’ genuine reactions. It seemed undeniable that the foreign contestants did much better in terms of vocals and stage presence than the Chinese ones. Some online commenters even said that the gap between Chinese and foreign singers’ levels was like “the difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival” [a local Chinese music festival].

Chinese online influencer Yongkai (@陈咏开165) shared screenshots of Chanté Moore’s backstage reactions during the show. The American celebrity seemed puzzled when hearing the somewhat underwhelming performance by Chinese singer Yang Chenglin (楊丞琳), and she appeared much more positive when Na Ying sang.

This noteworthy scene, coupled with Chanté’s comments during an interview saying that she thought the Chinese production team had invited her on the show to be a judge, turned the entire show into a display of foreign singers outshining the Chinese contestants.

By the end of the first episode, Chanté Moore and Faouzia unsurprisingly ranked first and second, with Na Ying in third place.

After the show, some online commenters jokingly pointed out that Na Ying, being of Manchu descent like the rulers of China during the Qing Dynasty, showed some similarities to Empress Dowager Cixi’s defiance against Western colonizers in the way she “single-handedly took up against on foreigners” on the show.

They humorously turned Na Ying’s expressions into memes resembling Empress Dowager Cixi from an old Chinese TV show, with captions like “I want the foreigners dead” (“我要洋人死”).

Others suggested finding better Chinese singers for the show who could compete with Faouzia and Moore.

“SINGING WELL” CULTURALLY COLONIZED?

“I’m in Zibo eating BBQ, I really don’t want to listen to Alicia Keys.”

Initially, discussions about the show were light-hearted and humorous, until some netizens who couldn’t appreciate the jokes began to dampen the mood and made online discussions more serious.

Zou Xiaoying (@邹小樱), a music critic with nearly two million followers, posted on social media after the show, stating that he would have never voted for Chanté Moore or Faouzia. Not only did Zou question their vocal talent, he also wondered if the aesthetic of Chinese listeners had been influenced by Western music taste to such an extent that it has been “culturally colonized” (“文化殖民”). Meanwhile, he praised the members of Beijing rock band Second Hand Rose as “national heroes” (“民族英雄”).

He wrote:

If I had three votes for the first episode of “Singer 2024,” I’d vote for Second Hand Rose, Na Ying, and Silence Wang [note: Chinese singer-songwriter and record producer Wang Sushuang 汪苏泷]. The reason I wouldn’t vote for Chanté Moore or Faouzia is because — do they actually sing so well?

Has our definition of “singing well” perhaps been colonized? Just as our modern-day use of Chinese has little to do with our classical Chinese poems, with the foundation of modern Chinese actually being translations from the 20th century, is this also a form of ‘cultural colonization’?

You must think I’m talking nonsense again. But when I listen to Chanté Moore singing “If I Ain’t Got You,” I find it too boring. I know her singing is “good,” but this “good” has nothing to do with me. If, for Chinese listeners, Chanté Moore’s “good” is the standard, then is that what we in the music industry should be working towards? Isn’t that funny? When you open QQ Music or NetEase Cloud Music, and it recommends these songs to you every day, won’t you be convinced to practice again?

Of course, I know Chanté Moore is in good shape, very relaxed. Actually all of the Chinese singers tonight were very nervous. Yang Chenglin (杨丞琳) was nervous, Na Ying was also nervous. Even a seemingly carefree band like Second Hand Rose, if you listened to the introduction of their song, [you’ll find] they were so nervous that Yao Lan, supposedly “China’s No.1 Guitarist”, was so nervous that he hit the wrong note. It was not even a fast-paced solo (…), how nervous could he be? When everyone’s so tense, the confidence of Chanté Moore and Faouzia is indeed something that East Asia can’t match. In East-Asian [entertainment] circles, represented by China/Japan/Korea, our different cultural habits, upbringing, and ethnic characteristics have made it so that we don’t possess these kinds of singing abilities, even including our ways of emotional expression. I don’t know from which season it started with ‘Singer’ – and if it’s some kind of Catfish Effect (鲶鱼效应 ) – that they brought international singers with different cultural backgrounds into the competition. But this isn’t the Olympics, it’s not like Liu Xiang [刘翔, Chinese gold medal hurdler] is going to defeat opponents from the United States or Cuba. “I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like Alicia Keys.” (This line is not mine, I stole it from my WeChat friend).

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Anyway, no matter if they’re strong or not, I would never vote for the foreigner.

The comment about ‘I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like [listening to] Alicia Keys’ refers to the craze surrounding China’s ‘BBQ town’ Zibo. In Zibo, Chinese visitors like to sing, drink beer, and enjoy food together; it’s a simple and modest way of appreciating life and music, which contrasts with slick and smooth American or foreign styles of performing and singing.

Whether Zou’s criticism was for attention or genuine sentiment, it shifted the focus of the discussion from music to patriotism.

CHINESE SINGERS WITH MILITARISTIC UNDERTONES

“I volunteer to join the battle”

Amidst all this, some netizens, easily swayed by nationalist sentiments, began to seek help from the “national team” (国家队) of singers — musicians employed by national-level arts troupes — to “bring glory to the nation” and teach the foreigners a lesson. Some even questioned the intentions of the Singer 2024 TV show in inviting foreign singers to participate.

On May 12th, renowned Chinese singer and philanthropist Han Hong (韩红) posted on Weibo, fueling a wave of sentiment and support. In her post, Han Hong declared, “I am Chinese singer Han Hong, and I volunteer to join the battle,” tagging the production team of the TV show. Her invitation to join the battle quickly went viral.

Han Hong meme: “Who called for me?”

Han Hong has significant influence in the Chinese music industry and society as a whole. Her usual serious demeanor and avoidance of internet pop culture made netizens unsure whether she was joking or serious. Nevertheless, regardless of her intentions, a group of well-known singers began to volunteer via Weibo, emphasizing their identity as “Chinese singers” and using phrases with strong militaristic undertones like “fighting for the country” and “answering the call.”

Although many enjoyed this new wave of national pride in Chinese music and performers, some netizens criticized the trend of transforming an entertainment show into a nationalistic competition.

Film critic He Xiaoqin (何小沁) stated, “It’s okay to take the Qing-Dynasty-fighting-foreigners comparison as a joke, but taking it too seriously in today’s context is absurd.”

Others expressed fatigue with how quickly topics on Chinese internet platforms escalate to patriotic sentiments. To bring the focus back to entertainment, they turned “I volunteer to join the battle” (#我请战#) into a new internet catchphrase.

In response, the production team of Singer 2024 released a statement on Weibo, thanking all the singers for their self-recommendations. They emphasized the show’s competitive structure but clarified that “winning” is just one part of a singer’s journey..but that the love of music goes beyond all in connecting people, no matter where they’re from.

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Online reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among Chinese netizens.

Published

3 months agoon

April 18, 2024

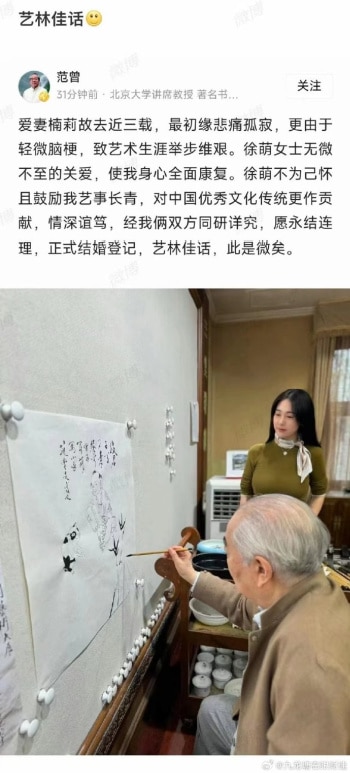

The recent marriage announcement of the renowned Chinese calligrapher/painter Fan Zeng and Xu Meng, a Beijing TV presenter 50 years his junior, has sparked online discussions about the life and work of the esteemed Chinese artist. Some netizens think Fan lacks the integrity expected of a Chinese scholar-artist.

Recently, the marriage of a 86-year-old Chinese painter to his bride, who is half a century younger, has stirred conversations on Chinese social media.

The story revolves around renowned Chinese artist, calligrapher, and scholar Fan Zeng (范曾, 1938) and his new spouse, Xu Meng (徐萌, 1988). On April 10, Fan announced their marriage through an online post accompanied by a picture.

In the picture, Fan is seen working on his announcement in calligraphic form.

Fan Zeng announces his marriage on Chinese social media.

In his writing, Zeng shares that the passing of his late wife, three years ago, left him heartbroken, and a minor stroke also hindered his work. He expresses gratitude for Xu Meng’s care, which he says led to his physical and mental recovery. Zeng concludes by expressing hope for “everlasting harmony” in their marriage.

Fan Zeng is a calligrapher and poet, but he is primarily recognized as a contemporary master of traditional Chinese painting. Growing up in a well-known literary family, his journey in art began at a young age. Fan studied under renowned mentors at the Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, including Wu Zuoren, Li Keran, Jiang Zhaohe, and Li Kuchan.

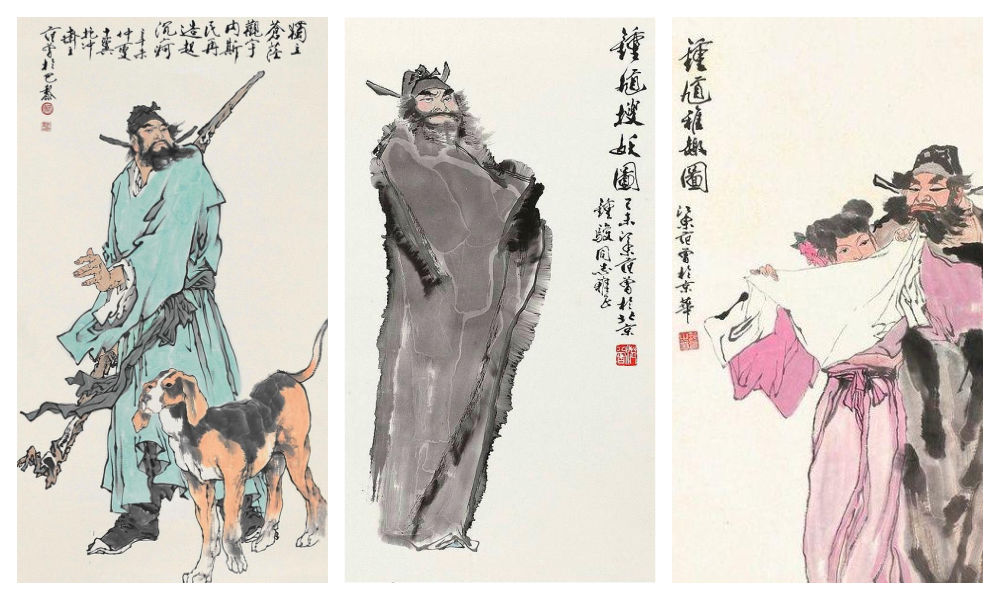

Fan gained global acclaim for his simple yet vibrant painting style. He resided in France, showcased his work in numerous exhibitions worldwide, and his pieces were auctioned at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in the 1980s.[1] One of Fan’s works, depicting spirit guardian Zhong Kui (钟馗), was sold for over 6 million yuan (828,000 USD).

Zhong Kui in works by Fan Zeng.

In his later years, Fan Zeng transitioned to academia, serving as a lecturer at Nankai University in Tianjin. At the age of 63, he assumed the role of head of the Nankai University Museum of Antiquities, as well as holding various other positions from doctoral supervisor to honorary dean.

By now, Fan’s work has already become part of China’s twentieth-century art history. Renowned contemporary scholar Qian Zhongshu once remarked that Fan “excelled all in artistic quality, painting people beyond mere physicality.”

A questionable “role model”

Fan’s third wife passed away in 2021. Later, he got to know Xu Meng, a presenter at China Traffic Broadcasting. Allegedly, shortly after they met, he gifted her a Ferrari, sparking the beginning of their relationship.

A photo of Xu and her Hermes Birkin 25 bag has also been making the rounds on social media, fueling rumors that she is only in it for the money (the bag costs more than 180,000 yuan / nearly 25,000 USD).

On Weibo, reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among netizens. Despite Fan’s reputation as a prominent philanthropist, many perceive his recent marriage as yet another instance of his lack of integrity and shamelessness.

Fan Zeng and Xu Meng. Image via Weibo.

One popular blogger (@好时代见证记录者) sarcastically wrote:

“Warm congratulations to the 86-year-old renowned contemporary erudite scholar and famous calligrapher Fan Zeng, born in 1938, on his marriage to Ms Xu Meng, a 50 years younger 175cm tall woman who is claimed to be China’s number one golden ratio beauty. Mr Fan Zeng really is a role model for us middle-aged greasy men, as it makes us feel much less uncomfortable when we’re pursuing post-90s youngsters as girlfriends and gives us an extra shield! Because if contemporary Confucian scholars [like yourself] are doing this, then we, as the inheritors of Confucian culture, can surely do the same!“

Various people criticize the fact that Xu Meng is essentially just an aide to Fan, as she can often be seen helping him during his work. One commenter wrote: “Couldn’t he have just hired an assistant? There’s no need to turn them into a bed partner.”

Others think it’s strange for a supposedly scholarly man to be so superficial: “He just wants her for her body. And she just wants him for his inheritance.”

“It’s so inappropriate,” others wrote, labeling Fan as “an old bull grazing on young grass” (lǎoniú chī nèncǎo 老牛吃嫩草).

Fan is not the only well-known Chinese scholar to ‘graze on young grass.’ The famous Chinese theoretical physicist Yang Zhenning (杨振宁, 1922), now 101 years old, also shares a 48-year age gap with his wife Weng Fen (翁帆). Fan, who is a friend of Yang’s, previously praised the love between Yang and Weng, suggesting that she kept him youthful.

Older photo posted on social media, showing Fan attending the wedding ceremony of Yang Zhenning and his 48-year-younger partner Weng Fen.

Some speculate that Fan took inspiration from Yang in marrying a significantly younger woman. Others view him as hypocritical, given his expressions of heartbreak over his previous wife’s passing, and how there’s only one true love in his lifetime, only to remarry a few years later.

Many commenters argue that Fan Zeng’s conduct doesn’t align with that of a “true Confucian scholar,” suggesting that he’s undeserving of the praise he receives.

“Mr. Wang from next door”

In online discussions surrounding Fan Zeng’s recent marriage, more reasons emerge as to why people dislike him.

Many netizens perceive him as more of a money-driven businessman rather than an idealistic artist. They label him as arrogant, critique his work, and question why his pieces sell for so much money. Some even allege that the only reason he created a calligraphy painting of his marriage announcement is to profit from it.

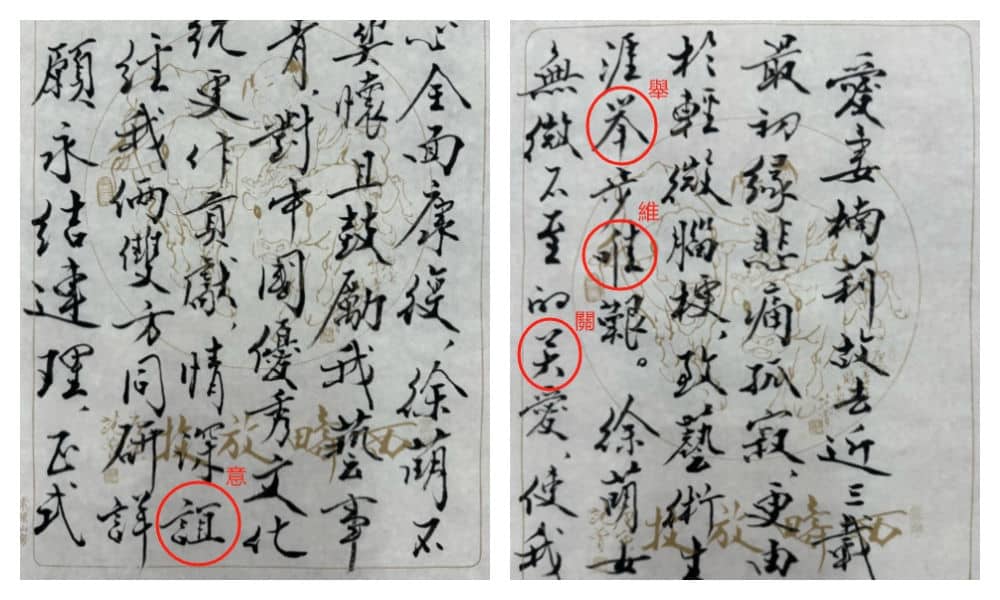

Others cast doubt on his status as a Chinese calligraphy ‘grandmaster,’ noting that his calligraphy style is not particularly impressive and may contain typos or errors. His wedding announcement calligraphy appears to blend traditional and simplified characters.

Netizens have pointed out what looks like errors or typos in Fan’s calligraphy.

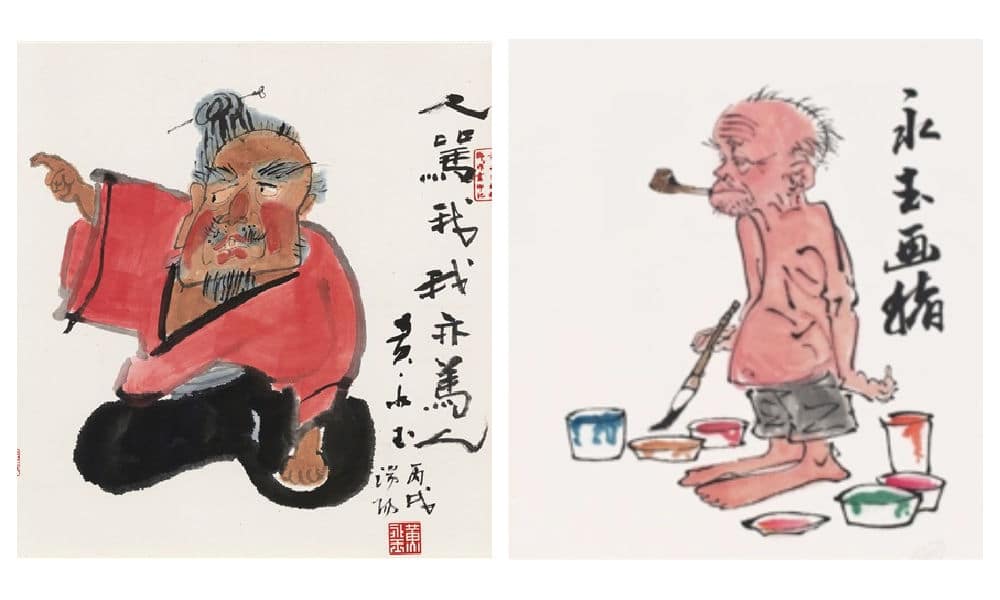

Another source of dislike stems from his history of disloyalty and his feud with another prominent Chinese painter, Huang Yongyu (黄永玉). Huang, who passed away in 2023, targeted Fan Zeng in some of his satirical paintings, including one titled “When Others Curse Me, I Also Curse Others” (“人骂我,我亦骂人”). He also painted a parrot, meant to mock Fan Zeng’s unoriginality.

Huang Yongyu made various works targeting Fan Zeng.

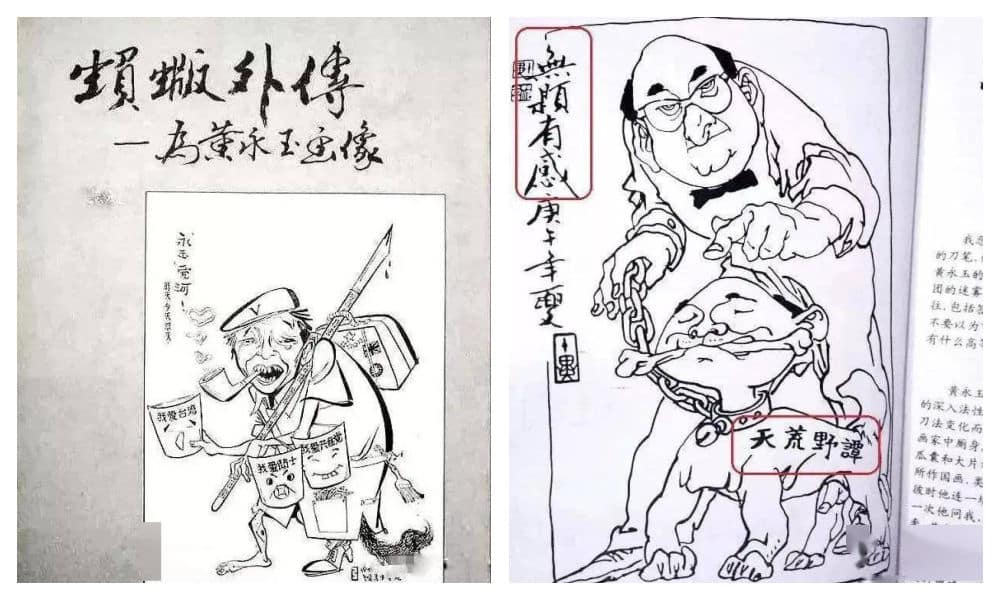

In retaliation, Fan produced his own works mocking Huang, sparking an infamous rivalry in the Chinese art world. The two allegedly almost had a physical fight when they ran into each other at the Beijing Hotel.

Fan Zeng mocked Huang Yongyu in some of his works.

Fan and Huang were once on good terms though, with Fan studying under Huang at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Through Huang, Fan was introduced to the renowned Chinese novelist Shen Congwen (沈从文, 1902-1988), Huang’s first cousin and lifelong friend. As Shen guided Fan in his studies and connected him with influential figures in China’s cultural circles, their relationship flourished.

However, during the Cultural Revolution, when Shen was accused of being a ‘reactionary,’ Fan Zeng turned against him, even going as far as creating big-character posters to criticize his former mentor.[2] This betrayal not only severed the bond between Shen and Fan but also ended Fan’s friendship with Huang, and it is still remembered by people today.

Fan Zeng’s behavior towards another former mentor, the renowned painter Li Kuchan (李苦禪, 1899-1983), was also controversial. Once Fan gained fame, he made it clear that he no longer respected Li as his teacher. Li later referred to Fan as “a wolf in sheep’s clothes,” and apparently never forgave him. Although the exact details of their falling out remain unclear, some blame Fan for exploiting Li to further his own career.

There are also some online commenters who call Fan Zeng a “Mr Wang from next door” (隔壁老王), a term jokingly used to refer to the untrustworthy neighbor who sleeps with one’s wife. This is mostly because of the history of how Fan Zeng met his third wife.

Fan’s first wife was the Chinese female calligrapher Lin Xiu (林岫), who came from a wealthy family. During this marriage, Fan did not have to worry about money and focused on his artistic endeavours. The two had a son, but the marriage ended in divorce after a decade. Fan’s second wife was fellow painter Bian Biaohua (边宝华), with whom he had a daughter. It seems that Bian loved Fan much more than he loved her.

It is how he met his third wife that remains controversial to this day. Nan Li (楠莉), formerly named Zhang Guiyun (张桂云), was married to performer Xu Zunde (须遵德). Xu was a close friend of Fan, and helped him out when Fan was still poor and trying to get by while living in Beijing’s old city center.

Wanting to support Fan’s artistic talent, Xu let Fan Zeng stay over, supported him financially, and would invite him for meals. Little did he know that while Xu was away to work, Fan enjoyed much more than meals alone; Fan and Xu’s wife engaged in a secret decade-long affair.

When the affair was finally exposed, Xu Zunde divorced his wife. Still, they would use his house to meet and often locked him out. Three years later, Nan Li officially married Fan Zeng. Xu not only lost his wife and friend but also ended up finding his house emptied, his two sons now bearing Fan’s surname.

When Nan Li passed away in 2021, Fan Zeng published an obituary that garnered criticism. Some felt that the entire text was actually more about praising himself than focusing on the life and character of his late wife, with whom he had been married for forty years.

Fan Zeng and his four wives

An ‘old pervert’, a ‘traitor’, a ‘disgrace’—there are a lot of opinions circulating about Fan that have come up this week.

Despite the negativity, a handful of individuals maintain a positive outlook. A former colleague of Xu Meng writes: “If they genuinely like each other, age shouldn’t matter. Here’s to wishing them a joyful marriage.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Song, Yuwu. 2014. Biographical Dictionary of the People’s Republic of China. United Kingdom: McFarland & Company, 76.

[2]Xu, Jilin. 2024. “Xu Jilin: Are Shen Congwen’s Tears Related to Fan Zeng?” 许纪霖:沈从文的泪与范曾有关系吗? The Paper, April 15. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_27011031. Accessed April 17, 2024.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?