China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Chinese Fashion First: Consumer Nationalism and ‘China Chic’

Consumer sentiments on Western brands and made-in-China fashion are changing.

Published

3 years agoon

WHAT’S ON WEIBO ARCHIVE | PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

At a time when Chinese media, celebrities, and consumers are condemning and boycotting Western brands, Chinese fashion and luxury brands are flourishing in a new era of “proudly made in China.”

This is the “WE…WEI…WHAT?” column by Manya Koetse, original publication in German by Goethe Institut China, see Goethe.de: WE…WEI…WHAT? Manya Koetse erklärt das chinesische Internet.

“The first thing Chinese fashion magazines should do is support the Chinese fashion industry, Chinese domestic brands, and Chinese designers!” In a video that went viral on social media, Hung Huang (洪晃), the famous American-Chinese television host and publisher of fashion magazine iLook, called out for a healthy development of China’s fashion industry that does not rely on Western brands to continue growing.

Hung Huang’s remarks were made in late March of 2021, around the time when a social media storm broke out in China over the Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) and its brand members – including H&M, Nike, and Adidas – for no longer sourcing cotton from China’s Xinjiang region. This boycott generated a huge backlash in mainland China. The online anger was mainly directed at H&M, since the Swedish retailer is a top member of the BCI and had previously released a statement on its site in which the company said it was “deeply concerned” over reports of alleged forced labor in the production of cotton in Xinjiang.

The news developments were followed by a wave of social media boycott campaigns and Chinese brand ambassadors cutting ties with international brands. It also ignited a social media movement in support of domestic brands, ‘made in China,’ and Xinjiang as China’s largest cotton-growing area.

The hashtag “I support Xinjiang cotton” (#我支持新疆棉花#) received a staggering 7.9 billion views on Weibo within a few weeks time. Simultaneously, a rising confidence in national brands became increasingly visible on social media, where the calls for supporting domestic brands are growing louder.

A recent survey by state media outlet Global Times suggests that most Chinese consumers believe that Western brands could be replaced by Chinese ones. The article claims that 75 percent of its survey respondents agree that “national products could fully or partially replace Western products.”

Proudly Made in China

Recent years have not just seen a rise in Chinese fashion brands, but also the emergence of a fashion scene where traditional Chinese elements play a major role. The Hanfu movement, for example, seeks to revitalize the wearing of Han Chinese ethnic clothing. But beyond that, brands are also weaving more Chinese themes into everyday fashion items such as sneakers and t-shirts.

China themed fashion on e-commerce platform Taobao.

The rise in popularity of Chinese fashion brands and styles was dubbed the “China Chic” trend by CGTN in 2020. “China Chic” is a translation of “guócháo” (国潮), which literally means “national tide,” referring to the rise of domestic brands, with their designs often incorporating culturally Chinese elements into the latest trends. In 2021, for the first time ever, the Spring Festival Gala (Chinese state media’s biggest live televised event) also included a fashion show to show the beauty of Chinese costumes to “demonstrate cultural confidence.”

With celebrity endorsements being one of the most important strategies for social media marketing, Chinese celebrities play a crucial role in this trend as guócháo ambassadors. Chinese actor and singer Xiao Zhan (肖战) was praised on social media for becoming the new brand ambassador of the Chinese sportswear brand Lining. When celebrity Wang Yibo became the spokesperson for the domestic brand Anta Sports, one Weibo hashtag page on the topic received over one billion views (#王一博代言安踏#) in late April of 2021. The promotional poster featuring Wang Yibo shows him wearing a t-shirt with “China” on it, including the national flag – profiling Anta as a nation-loving brand.

The rising popularity of ‘made in China’ fashion is noteworthy in a consumer culture where Western brands are often viewed as being of higher quality than domestically produced fashion. The very fact that these foreign brands succeeded in gaining access to China’s market is, in the eyes of many consumers, a reason to believe they must be of higher quality.[1] Those sentiments now seem to be shifting.

A recent Chinese short documentary produced by Tmall titled “Proudly Made in China” (爆款中国) discusses how Western brands have dominated the Chinese fashion and luxury market for years, making it more difficult for Chinese brands to become big players in their own field.

“Why are Chinese brands not as highly accepted by Chinese consumers?”, asks Li Jiaqi (李佳琦), an influencer and new brand recruiter for Tmall who is featured in the short film: “Why do Chinese consumers seem to have a preconceived and biased view that Chinese products are of poor quality?”

In the short film, Li explains that Chinese consumers have since long had worries about buying Chinese brands, and that one slight problem with a product will automatically negatively reflect on the entire brand.

Existing consumer preferences for Western brands have even created the idea that Chinese brands should register abroad and pose as a foreign brand to enlarge their chances to succeed in the Chinese market.

China’s flourishing live-streaming market and domestic e-commerce platforms have provided new opportunities for Chinese brands to shine once their products gain consumer recognition. Especially younger consumers, those born after 1995 or 2000, show more confidence in Chinese brands than the generations before them.

In the “Proudly Made in China” film, this growing trust in domestic brands among Chinese younger generations is linked to a striking confidence and pride in China, its national identity, and its culture. On Weibo, some commenters replied: “This is the era of domestic brands!”

Western Brand Controversies

Although the influence of national pride on China’s young consumers might already have been strong before, there are also changing dynamics in the relation between Chinese consumers and Western brands which seem to have boosted the ‘guócháo’ and domestic brand trend; Chinese brands have been cast in a more positive light over the past few years due to the controversies involving Western brands.

In 2018, Italian fashion house Dolce & Gabbana (D&G) faced consumer outrage in China for publishing a culturally insensitive advertising campaign that showed a Chinese model clumsily using chopsticks to eat Italian dishes such as pizza, cannoli, and spaghetti. The campaign, which was titled “D&G Loves China,” completely backfired with many finding it racist and sexist and vowing to boycott the brand. The controversy became so big that a big D&G fashion show in Shanghai was canceled and the company saw a slump in its business on the mainland.

Still from the promotional D&G video that was deemed racist in China, causing major controversy in 2018 (whatsonweibo).

In 2019, many different international fashion brands, including Versace, Coach, Calvin Klein, Givenchy, and ASICS, were condemned by Chinese netizens for listing Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan as separate countries or regions – not part of China – on their official websites or brand T-shirts. Chinese celebrities cut their collaborations with many of these brands.

When in 2020 the aforementioned Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) announced that it was ceasing all operations in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region amid accusations of “forced labor” there, backlash in China further grew against the organization and the brands affiliated to it. As reported by CGTN, BCI has recently removed its statement on Xinjiang cotton from its website (allegedly this was related to a cyber attack), but the discussions on the position of Western brands in China continue, with both state media and netizens sending out the message that “foreign companies that slander China” are not welcome in the country.

The Future of Fashion Brands in China

“Boycott Nike? Support domestic brands? What are we supposed to do now?” It is a question posed by the Chinese ‘Sneakersbar’ vlogger Fang (@鞋吧Sneakersbar), a sportswear-focused self-media account with over 3,5 million followers on Weibo. The question resonates with many consumers, who are caught between politics, patriotism, and personal preferences for certain brands.

In their latest video, Sneakersbar makes up the balance on where Western brands, especially those affiliated with BCI, stand in the Chinese market today. On the one hand, Fang argues, many foreign brands, including Adidas, Nike, H&M, Uniqlo, and others, have already become part of China’s commercial fashion landscape and many consumers love these brands and their products. On the other hand, these foreign brands are also making political choices that Chinese consumers cannot ignore. But does this mean they should be boycotted forever? Does it mean that you should look down on others buying these products?

The video by popular weibo account Sneakersbar: “Boycott Nike? Support Domestic Brands? What are we supposed to do?”

The answer is that consumers should stay rational in their choices, Fang argues. This means that choosing Chinese brands out of a form of “rational patriotism” is fine, but people should not attack others merely because they wear foreign brands or work in their shops. The same goes for those consumers who only want to buy foreign brands just because they are foreign; they could also consider Chinese products to support domestic brands – especially those brands which refrain from copying foreign ones and have developed their own unique designs and styles.

Many commenters on Weibo support Fang’s message of “reasonable patriotism without blind worship” (“理性爱国,也不盲目崇拜”), supporting the idea that Western and Chinese brands can co-exist and that they can be competitors in a market where Chinese fashion labels are getting more room to grow.

“Nationalism and patriotism offer opportunities for Chinese brands,” one Weibo user writes: “China Chic and China fashion trends are putting more pressure on foreign brands. Because of the speedy rise of Chinese domestic brands, which are producing high-quality products and are applying smart marketing methods, more and more patriotic young people are buying their products.”

It is clear that many consumers in China support domestic brands and hope that Chinese fashion can flourish within its own market. But there are also those voices stressing the importance of consumers’ freedom to buy the brands that suit them, wherever they are from and regardless of politics. One person commented: “Western or Chinese brand, I just want to wear the shoes that are most comfortable for me to walk in.”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

[1] Tian, Kelly and Lily Dong. 2011. Consumer-Citizens of China: The Role of Foreign Brands in the Imagined Future of China. London & New York: Routledge. Page 7.

This text was written for Goethe-Institut China under a CC-BY-NC-ND-4.0-DE license (Creative Commons) as part of a monthly column in collaboration with What’s On Weibo.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Who’s gonna buy this Zara dress in China? “I’m afraid that someone will say I stole the apron from Haidilao.”

Published

7 days agoon

April 19, 2024

A short dress sold by Zara has gone viral in China for looking like the aprons used by the popular Chinese hotpot chain Haidilao.

“I really thought it was a Zara x Haidialo collab,” some customers commented. Others also agree that the first thing they thought about when seeing the Zara dress was the Haidilao apron.

The “original” vs the Zara dress.

The dress has become a popular topic on Xiaohongshu and other social media, where some images show the dress with the Haidilao logo photoshopped on it to emphasize the similarity.

One post on Xiaohongshu discussing the dress, with the caption “Curious about the inspiration behind Zara’s design,” garnered over 28,000 replies.

Haidilao, with its numerous restaurants across China, is renowned for its hospitality and exceptional customer service. Anyone who has ever dined at their restaurants is familiar with the Haidilao apron provided to diners for protecting their clothes from food or oil stains while enjoying hotpot.

These aprons are meant for use during the meal and should be returned to the staff afterward, rather than taken home.

The Haidilao apron.

However, many people who have dined at Haidilao may have encountered the following scenario: after indulging in drinks and hotpot, they realize they are still wearing a Haidilao apron upon leaving the restaurant. Consequently, many hotpot enthusiasts may have an ‘accidental’ Haidilao apron tucked away at home somewhere.

This only adds to the humor of the latest Zara dress looking like the apron. The similarity between the Zara dress and the Haidilao apron is actually so striking, that some people are afraid to be accused of being a thief if they would wear it.

One Weibo commenter wrote: “The most confusing item of this season from Zara has come out. It’s like a Zara x Haidilao collaboration apron… This… I can’t wear it: I’m afraid that someone will say I stole the apron from Haidilao.”

Funnily enough, the Haidilao apron similarity seems to have set off a trend of girls trying on the Zara dress and posting photos of themselves wearing it.

It’s doubtful that they’re actually purchasing the dress. Although some commenters say the dress is not bad, most people associate it too closely with the Haidilao brand: it just makes them hungry for hotpot.

By Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Zibo had its BBQ moment. Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine with its special take on malatang. Tourism marketing in China will never be the same again.

Published

4 weeks agoon

April 1, 2024

Since the early post-pandemic days, Chinese cities have stepped up their game to attract more tourists. The dynamics of Chinese social media make it possible for smaller, lesser-known destinations to gain overnight fame as a ‘celebrity city.’ Now, it’s Tianshui’s turn to shine.

During this Qingming Festival holiday, there is one Chinese city that will definitely welcome more visitors than usual. Tianshui, the second largest city in Gansu Province, has emerged as the latest travel hotspot among domestic tourists following its recent surge in popularity online.

Situated approximately halfway along the Lanzhou-Xi’an rail line, this ancient city wasn’t previously a top destination for tourists. Most travelers would typically pass through the industrial city to see the Maiji Shan Grottoes, the fourth largest Buddhist cave complex in China, renowned for its famous rock carvings along the Silk Road.

But now, there is another reason to visit Tianshui: malatang.

Gansu-Style Malatang

Málàtàng (麻辣烫), which literally means ‘numb spicy hot,’ is a popular Chinese street food dish featuring a diverse array of ingredients cooked in a soup base infused with Sichuan pepper and dried chili pepper. There are multiple ways to enjoy malatang.

When dining at smaller street stalls, it’s common to find a selection of skewered foods—ranging from meats to quail eggs and vegetables—simmering in a large vat of flavorful spicy broth. This communal dining experience is affordable and convenient for solo diners or smaller groups seeking a hotpot-style meal.

In malatang restaurants, patrons can usually choose from a selection of self-serve skewered ingredients. You have them weighed, pay, and then have it prepared and served in a bowl with a preferred soup base, often with the option to choose the level of spiciness, from super hot to mild.

Although malatang originated in Sichuan, it is now common all over China. What makes Tianshui malatang stand out is its “Gansu-style” take, with a special focus on hand-pulled noodles, potato, and spicy oil.

An important ingredient for the soup base is the somewhat sweet and fragrant Gangu chili, produced in Tianshui’s Gangu County, known as “the hometown of peppers.”

Another ingredient is Maiji peppercorns (used in the sauce), and there are more locally produced ingredients, such as the black fungi from Qingshui County.

One restaurant that made Tianshui’s malatang particularly famous is Haiying Malatang (海英麻辣烫) in the city’s Qinzhou District. On February 13, the tiny restaurant, which has been around for three decades, welcomed an online influencer (@一杯梁白开) who posted about her visit.

The vlogger was so enthusiastic about her taste of “Gansu-style malatang,” that she urged her followers to try it out. It was the start of something much bigger than she could have imagined.

Replicating Zibo

Tianshui isn’t the first city to capture the spotlight on Chinese social media. Cities such as Zibo and Harbin have previously surged in popularity, becoming overnight sensations on platforms like Weibo, Xiaohongshu, and Douyin.

This phenomenon of Chinese cities transforming into hot travel destinations due to social media frenzy became particularly noteworthy in early 2023.

During the Covid years, various factors sparked a friendly competition among Chinese cities, each competing to attract the most visitors and to promote their city in the best way possible.

The Covid pandemic had diverse impacts on the Chinese domestic tourism industry. On one hand, domestic tourism flourished due to the pandemic, as Chinese travelers opted for destinations closer to home amid travel restrictions. On the other hand, the zero-Covid policy, with its lockdowns and the absence of foreign visitors, posed significant challenges to the tourism sector.

Following the abolition of the zero-Covid policy, tourism and marketing departments across China swung into action to revitalize their local economy. China’s social media platforms became battlegrounds to capture the attention of Chinese netizens. Local government officials dressed up in traditional outfits and created original videos to convince tourists to visit their hometowns.

Zibo was the first city to become an absolute social media sensation in the post-Covid era. The old industrial and mining city was not exactly known as a trendy tourist destination, but saw its hotel bookings going up 800% in 2023 compared to pre-Covid year 2019. Among others factors contributing to its success, the city’s online marketing campaign and how it turned its local BBQ culture into a unique selling point were both critical.

Zibo crowds, image via 163.com.

Since 2023, multiple cities have tried to replicate the success of Zibo. Although not all have achieved similar results, Harbin has done very well by becoming a meme-worthy tourist attraction earlier in 2024, emphasizing its snow spectacle and friendly local culture.

By promoting its distinctive take on malatang, Tianshui has emerged as the next city to captivate online audiences, leading to a surge in visitor numbers.

Like with Zibo and Harbin, one particular important strategy used by these tourist offices is to swiftly respond to content created by travel bloggers or food vloggers about their cities, boosting the online attention and immediately seizing the opportunity to turn online success into offline visits.

A Timeline

What does it take to become a Chinese ‘celebrity city’? Since late February and early March of this year, various Douyin accounts started posting about Tianshui and its malatang.

They initially were the main reason driving tourists to the city to try out malatang, but they were not the only reason – city marketing and state media coverage also played a role in how the success of Tianshui played out.

Here’s a timeline of how its (online) frenzy unfolded:

- July 25, 2023: First video on Douyin about Tianshui’s malatang, after which 45 more videos by various accounts followed in the following six months.

- Feb 5, 2024: Douyin account ‘Chuanshuo Zhong de Bozi’ (传说中的波仔) posts a video about malatang streetfood in Gansu

- Feb 13, 2024: Douyin account ‘Yibei Liangbaikai’ (一杯梁白开) posts a video suggesting the “nationwide popularization of Gansu-style malatang.” This video is an important breakthrough moment in the success of Tianshui as a malatang city.

- Feb – March ~, 2024: The Tianshui Culture & Tourism Bureau is visiting sites, conducting research, and organizing meetings with different departments to establish the “Tianshui city + malatang” brand (文旅+天水麻辣烫”品牌) as the city’s new “business card.”

- March 11, 2024: Tianshui city launches a dedicated ‘spicy and hot’ bus line to cater to visitors who want to quickly reach the city’s renowned malatang spots.

- March 13-14, 2024: China’s Baidu search engine witnesses exponential growth in online searches for Tianshui malatang.

- March 14-15, 2024: The boss of Tianshui’s popular Haiying restaurant goes viral after videos show him overwhelmed and worried he can’t keep up. His facial expression becomes a meme, with netizens dubbing it the “can’t keep up-expression” (“烫不完表情”).

The worried and stressed expression of this malatang diner boss went viral overnight.

- March 17, 2024: Chinese media report about free ‘Tianshui malatang’ wifi being offered to visitors as a special service while they’re standing in line at malatang restaurants.

- March 18, 2024: Tianshui opens its first ‘Malatang Street’ where about 40 stalls sell malatang.

- March 18, 2024: Chinese local media report that one Tianshui hair salon (Tony) has changed its shop into a malatang shop overnight, showing just how big the hype has become.

- March 21, 2024: A dedicated ‘Tianshui malatang’ train started riding from Lanzhou West Station to Tianshui (#天水麻辣烫专列开行#).

- March 21, 2024: Chinese actor Jia Nailiang (贾乃亮) makes a video about having Tianshui malatang, further adding to its online success.

- March 30, 2024: A rare occurrence: as the main attraction near Tianshui, the Maiji Mountain Scenic Area announces that they’ve reached the maximum number of visitors and don’t have the capacity to welcome any more visitors, suspending all ticket sales for the day.

- April 1, 2024: Chinese presenter Zhang Dada was spotted making malatang in a local Tianshui restaurant, drawing in even more crowds.

A New Moment to Shine

Fame attracts criticism, and that also holds true for China’s ‘celebrity cities.’

Some argue that Tianshui’s malatang is overrated, considering the richness of Gansu cuisine, which offers much more than just malatang alone.

When Zibo reached hype status, it also faced scrutiny, with some commenters suggesting that the popularity of Zibo BBQ was a symptom of a society that’s all about consumerism and “empty social spectacle.”

There is a lot to say about the downsides of suddenly becoming a ‘celebrity city’ and the superficiality and fleetingness that comes with these kinds of trends. But for many locals, it is seen as an important moment as they see their businesses and cities thrive.

Even after the hype fades, local businesses can maintain their success by branding themselves as previously viral restaurants. When I visited Zibo a few months after its initial buzz, many once-popular spots marketed themselves as ‘wanghong’ (网红) or viral celebrity restaurants.

For the city itself, being in the spotlight holds its own value in the long run. Even after the hype has peaked and subsided, the gained national recognition ensures that these “trendy” places will continue to attract visitors in the future.

According to data from Ctrip, Tianshui experienced a 40% increase in tourism spending since March (specifically from March 1st to March 16th). State media reports claim that the city saw 2.3 million visitors in the first three weeks of March, with total tourism revenue reaching nearly 1.4 billion yuan ($193.7 million).

There are more ripple effects of Tianshui’s success: Maiji Shan Grottoes are witnessing a surge in visitors, and local e-commerce companies are experiencing a spike in orders from outside the city. Even when they’re not in Tianshui, people still want a piece of Tianshui.

By now, it’s clear that tourism marketing in China will never be the same again. Zibo, Harbin, and Tianshui exemplify a new era of destination hype, requiring a unique selling point, social media success, strong city marketing, and a friendly and fair business culture at the grassroots level.

While Zibo’s success was largely organic, Harbin’s was more orchestrated, and Tianshui learned from both. Now, other potential ‘celebrity’ cities are preparing to go viral, learning from the successes and failures of their predecessors to shine when their time comes.

By Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Where to Eat and Drink in Beijing: Yellen’s Picks

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

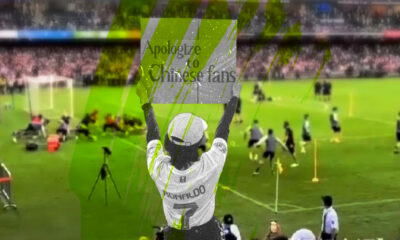

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

In Hot Water: The Nongfu Spring Controversy Explained

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight2 months ago

China Insight2 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

-

China Media2 months ago

China Media2 months agoParty Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

-

China World2 months ago

China World2 months agoFrom Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)