China and Covid19

These Were the Biggest Trends on Chinese Social Media in 2022 from A to Z

Oh dear, what a year. Here’s an overview of the 26 biggest trending topics on Chinese social media in 2022.

Published

2 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

What were the most discussed topics on Weibo in 2022? As we’re entering 2023, here is an overview of the top stories on Chinese social media from A to Z: a look back at the biggest trends on Chinese social media of the past year (please note that this is content for premium members only, subscribe here to read)

The year 2022 has been an eventful one on Chinese social media. Especially in times of lockdown, many people turned to social media to vent their feelings of frustration and anger, and some of the biggest topics were those that mostly played out in the online environment while the streets were empty.

2022 was initially also called ‘2020 too’, since the major lockdowns in cities such as Xi’an and Shanghai brought back memories of Wuhan in 2020.

But the year turned out to be very different from 2020 in many ways. While strict Covid regulations dominated many of the trending topics lists for a long time, the sudden shift in measures and the end of ‘zero Covid’ meant a huge break from everything that happened in 2020.

This year was also very different from 2021. Last year, major events such as the 100th anniversary of the Communist Party, heightened tensions with the U.S., and the Henan flood disaster, brought people together and there was a clear sense of unity. That also changed this year, when people protested against local Covid lockdowns, against excessive measures, and also disagreed with each other about the future of Covid in China and whether to keep fighting the virus or to live with it.

To give you more insight into the topics that went trending this year and which were most discussed by Chinese netizens, we have compiled this list of Weibo trends for you, from A-Z.

A is for: A4 Protests

A big fire that occurred in Urumqi on November 24th killed ten residents and injured nine others. The fire took place in the city’s Tianshan District, an area that had seen local outbreaks and lockdowns since August of 2022.

The tragic fire led to more public attention to the Covid lockdown situation in Urumqi and while people across China mourned the victims, they also expressed anger over how the last 100 days of their lives were spent in (semi)lockdown.

In the days after the fire, protests started erupting in various places across the country. Students in Nanjing and Xi’an gathered on campus grounds to make their voices heard, people also came together in Beijing, in the streets of Shanghai, in Wuhan, Chengdu, and in other places. Because people took to the streets holding up white papers, some dubbed this the “A4 Revolution.” The blank sheets were used as a sign of protest against censorship and stringent Covid measures.

Just days after the protests, Chinese health officials announced that changes were coming and on December 7th ten new Covid rules were introduced that basically ended China’s Zero Covid era (read more).

B is for: Barbie Hsu vs Wang Xiaofei

It’s the messy divorce drama that was one of the biggest celebrity topics of the year: Taiwanese actress Barbie Hsu (‘Big S’) and mainland Chinese businessman Wang Xiaofei got divorced and aired their dirty laundry (or actually, their dirty mattress) on Chinese social media. The ongoing drama started after ‘Big S’ accused her ex-husband of failing to pay alimony, the accumulated amount allegedly being over $160,000.

Wang Xiaofei publicly and angrily responded to Hsu’s accusations via multiple emotional posts on his Weibo account, where he has over seven million followers. Everyone and everything got dragged into the drama, from Wang’s mother to Barbie Hsu’s sister, her brother-in-law and new partner. One of Wang’s posts mentioned an incredibly expensive custom-made mattress that Barbie Hsu was still sleeping on with her new husband.

November 23rd became ‘Mattress D-day’ after it became known that Barbie Hsu had delivered the much-talked-about mattress to the S Hotel in Taipei, which Wang owns. The mattress was then publicly destroyed, with cameras and reporters standing by to see it being cut open and it was later burnt – ‘mattress gate’ was even live-streamed by Taiwanese media. With the mattress incident going viral, many netizens soon guessed that if it was such an expensive mattress, it must have been one by the Swedish Hästens company. Hästens (海丝腾) itself then responded to the drama via Weibo claiming that their mattresses are of such good quality that they would never go up in flames (read more).

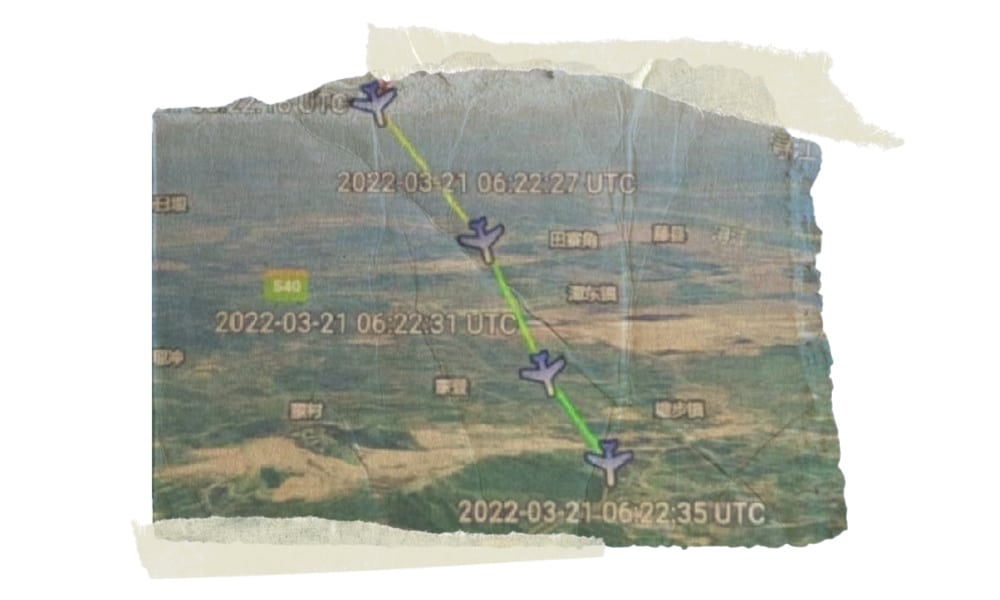

C is for: China Eastern Airlines Flight MU5735

Flight MU5735 became the number one news topic on Chinese social media on March 21st of 2022 after it was confirmed that the flight, carrying 132 people, had crashed in Guangxi province. The Boeing 737 was scheduled to fly from the southwestern city of Kunming to Guangzhou, but the plane dropped from the radar near the city of Wuzhou, Teng county, shortly before 14:30 local time, approximately half an hour before it was scheduled to land at Guangzhou.

The flight had already attracted attention on social media because the real-time flight tracking map Flightradar24 had shown the flight dropped some 7000 meters within 120 seconds. Some people tracking the flight thought it must have been a bug. Shocking footage later showed how the flight nosedived, plunging from the sky.

While rescue workers were still searching for the second black box, Chinese state media confirmed that all passengers and crew members were killed in the crash. Although a preliminary report about the crash stated that there were no unusual weather circumstances nor abnormal communications before the crash occurred, a final report on the crash still has not come out (#东航mu5735坠毁最新消息#).

D is for: Dabai

Chinese anti-epidemic workers dressed in hazmat suits have come to be nicknamed ‘dabai’ (dàbái 大白), which literally means ‘big white’ but is also a reference to the big white medical assistant robot Baymax in Disney’s Big Hero 6. Although the dàbái have been around ever since Wuhan 2020, they become a social media phenomenon in 2022, when it temporarily became all the rage for people to dance and sing for Covid-19 frontline healthcare workers in China.

What started as a cute gesture to show appreciation turned into a major hype, and the phenomenon of dancing for dabai was criticized by many who deemed this trend was not actually about gratitude but about attracting clicks and attention.

In 2022, there has been a shift in public views on dabai. Although people initially praised them and posted cute memes and videos about anti-epidemic workers, sentiments changed as frustrations over Covid measures grew in light of increasing outbreaks throughout the country and more viral videos showed altercations between local residents and the dabai working in their communities.

E is for: Excessive Measures

Excessive Covid measures received a lot of attention on Chinese social media this year. Although there was polarization between two epidemic ‘camps’ – namely those advocating opening up and those supporting zero Covid policies -, the majority of people agreed that excessive Covid measures were a big problem in many Chinese cities and counties in 2022.

Excessive Covid measures caused a significant delay when one toddler in Lanzhou needed emergency medical help after a carbon monoxide poisoning. The little boy passed away and the incident became a major story on Weibo. Excessive Covid measures also led to anger in Heilongjiang when local officials went around shops seeing if shopkeepers wore their masks at all times and asked for Health Codes before welcoming customers (more here).

Another time when excessive Covid measures particularly became a trending topic on Chinese social media is when local anti-epidemic workers at the harbor in Xiamen started testing fish, fresh off the boat, for Covid by swabbing their mouths. “I thought fish didn’t any lungs?” a popular comment said, with other commenters suggesting that this news made it clear that Covid “doesn’t affect the lungs but the brain instead.”

F is for: Foxconn Unrest

An exodus of Foxconn workers in Zhengzhou became a major topic on Chinese social media in October of 2022. A mismanagement of a big Covid outbreak at the huge ‘factory city’ – the world’s largest iPhone factory – led employees to leave the locked-down campus, starting their long journey home on foot.

Over a month after that initial exodus and unrest, protests broke out within the factory city as new workers had been recruited and were allegedly promised different things than the situation they faced at the ground. Foxconn was said to have promised that new workers and original workers would live separately, but in reality they were all sent to live in the same dorm buildings where employees with Covid were also staying. When the new workers also discovered that subsidy policies they agreed to were different from what they actually got, it caused panic and anger, and protests ensued. Because it was the second big wave of unrest at Foxconn Zhengzhou, the protest was also referred to as the “Foxconn Workers Movement 2.0” (富士康2.0工人运动) (read more).

G is for: Guizhou Bus Crash

Tragic accidents involving buses have happened in China before, but this year one bus accident particularly attracted the public’s attention because it involved a bus taking people to a mandatory quarantine facility. After the bus crashed in Guizhou province and fell into a deep ditch by the side of the road in the middle of the night on 18 September, 27 people died and 20 were left with injuries. The bus reportedly was taking people to a quarantine hotel in Qiannan prefecture for medical observation and isolation.

The incident triggered anger at a time when frustrations were already building over lockdowns and mandatory quarantines. Why was the bus taking people away in the middle of the night? Why were social media posts about the incident taken offline? Although local authorities later apologized for the accident, this incident – together with a number of other tragic incidents that happened around the same time – contributed to more dissatisfaction and a sense of despair over China’s zero Covid policies.

H is for: Homecoming

The Chinese movie Home Coming (万里归途) was the National Holiday film hit of the year. The movie is inspired by China’s overseas citizens protection response during the 2011 Libya crisis, and sparked waves of nationalistic sentiments among moviegoers. After its cinema debut, the film recurringly became a trending topic, especially after the movie’s box office sales went through the roof.

Home Coming was directed by Rao Xiaozhi (饶晓志) and features major Chinese actors such as Zhang Yi (张译), Wang Junkai (王俊凯) and Yin Tao (殷桃). The film tells the story of Chinese diplomats Zong Dawei (大伟与) and Cheng Lang (成朗), who are ordered to assist in the evacuation of overseas Chinese when war breaks out in North Africa in 2011. Just when they think they’ve successfully completed their mission, they learn they have to return to save a group of 125 compatriots who are still left behind.

I is for: IP Address

In 2022, Sina Weibo introduced a new function that displays the IP location of users posting on the platform. Weibo experimented with the function since 22 March of this year before completely rolling it out on 28 April. According to Sina Weibo, the function was introduced to ensure a “healthy and orderly discussion atmosphere” on the platform and to reduce the spread of fake news and invidious rumors by people pretending to be part of an issue or city that they are actually not part of. The function can not be turned off by users.

The new function became a trending topic and also led to some banter as the account of Bill Gates unexpectedly turned out to be located in Henan province, and Lionel Messi’s location showed up as Shanghai (read more).

J is for: Jiang Zemin

Former Chinese leader Jiang Zemin passed away at the age of 96 in November 2022. Until 2002, Jiang was a Party leader for thirteen years during which a lot happened for China when it comes to economic developments and international relations. After Jiang’s death was made public, social media flooded with posts and videos commemorating him.

Over the past decade, and especially since his 90th birthday, the former leader became somewhat of a social media phenomenon among younger Chinese internet users who showed their appreciation for Jiang, mainly due to his particular way of dressing, his flamboyant but nuanced media appearances, his knowledge of languages, and perhaps especially due to the fact that he often showed emotions during interviews and public appearances – which all poses a stark contrast to current leader Xi Jinping.

K is for: Kris Wu

The Chinese-Canadian superstar Kris Wu, better known as Wu Yifan (吴亦凡), previously dominated Chinese social media in the summer of 2021, when news of his detainment over rape allegations lead to an explosion of comments on Weibo. The 19-year-old student Meizhu Du (都美竹) was the first to accuse Wu of predatory behavior online, with at least 24 more women also coming forward claiming the celebrity showed inappropriate behavior and luring young women into sexual relationships. Wu was formally arrested on suspicion of rape in mid-August 2021.

In November of 2022, a preliminary court ruling came out in the criminal case in which Wu was accused of rape and other sex crimes. The Beijing Chaoyang district court found Wu guilty of raping three women in his home in 2020 and of “gathering people to commit adultery.” He was sentenced to 13 years in prison followed by deportation (read more).

L is for: Liu Xuezhou

The story of Liu Xuezhou was overshadowed by all the Covid-related topics that went top trending this year, but nevertheless, his account made a deep impression on many Chinese netizens in 2022.

Liu Xuezhou was just a teenager when he posted a video on social media in late 2021 asking for help in finding his biological parents. This video would be the start of a story followed by millions of Chinese netizens. Many people supported Liu and wanted to help the teenage boy, who was thought to have been kidnapped as a baby and then bought by his adoptive parents through an intermediary.

Thanks to the internet and some external help, Liu ended up finding his biological parents. But what was supposed to be a happy reunion turned out to be a bitter disappointment. Liu soon learned that he had not been abducted as a child, but that he had been sold on purpose by his father. Liu later shared how heartbroken he was to learn about how he was sold to pay for his mother’s bride price and how his parents never searched for him.

It was all too much for the teenage boy. In an online farewell letter, he expressed the hope that his traffickers and biological parents would be punished for their deeds. Liu was later found to have committed suicide within a month after meeting his biological parents at the age of just 15 years old (read more).

M is for: Mother of Eight

In late January of 2022, right around the same time when Liu Xuezhou was one of the biggest topics on Chinese social media, a TikTok video showing a woman chained up in a shed went viral online and triggered massive outrage with thousands of people demanding answers about the woman’s circumstances. The video showed how the woman was kept in a dirty hut without a door in the freezing cold. She did not even wear a coat, and she seemed confused and unable to express herself.

The video, which concerned a woman from Xuzhou who was a mother of eight children, caused a storm on social media. Many netizens worried about the woman’s circumstances. Why was she chained up? Was she a victim of human trafficking? Was she being abused? How could she have had eight babies? While netizens were speculating about the case and venting their anger, Weibo shut down some of the hashtags dedicated to this topic, but the topic soon popped up everywhere, and people started making artworks and writing essays in light of the case.

Thanks to the ongoing social media attention surrounding the woman, and with the help of local authorities, it was eventually determined that the woman was indeed a victim of human trafficking and she was identified as Xiao Huamei (小花梅) from Yagu, Fugong county, who went missing (without anyone reporting her missing) in 1996. Although still many questions linger around the case of Xiao Huamei, what is clear is that she now has come to represent many women like her (read more).

N is for: Nancy Pelosi

“The Old Witch has landed” was a much recurring phrase on Chinese social media on 2 August 2022. The so-called “Old Witch” was US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and for the entire day, anyone who was online was closely following the latest developments regarding her potential visit to Taiwan. Up to the moment the plane touched down, Chinese bloggers and political commentators came up with different prediction scenarios as to whether Pelosi would really arrive in Taipei, how Chinese military would respond, and what such a visit might mean at a time of already strained US-China relations.

Shortly after Pelosi indeed arrived in Taiwan, online livestreams covering the event stopped, and the local servers for China’s leading social media platform Weibo temporarily went down. Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan was not just one of the biggest social media topics in China of 2022, it was also certainly one of the most-watched flight radar events ever.

Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan was highly controversial and was seen as provocative. A new wave of national pride and expressions of nationalism flooded social media after China announced countermeasures in response to Pelosi’s visit and began live-fire military drills around Taiwan (read more).

O is for: Olympics

At 20:00 o’clock China time on 4 February, the much-anticipated Opening Ceremony of the Winter Olympics took place at the National Stadium in the Chinese capital. In early 2022, Beijing 2022 mascots ‘Bing Dwen Dwen’ and ‘Shuey Rhon Rhon’ popped up everywhere amid the spectacle that went trending all over Chinese social media. On social media, there was a sense of pride about China successfully organizing the Olympics in epidemic times.

But the one who really stole the limelight from Bing Dwen Dwen and Shuey Rhon Rhon was the 18-year-old Chinese American freestyle skier Gu Ailing (谷爱凌 Eileen Gu), who became an absolute social media sensation in China. After grabbing the medals for China, the “snow princess” was widely celebrated for her athletic talent and disarming smile.

For many, Gu turned out to be an inspiration, not just for being hard-working and smart – she was admitted to Stanford, – but also for not being afraid to speak her mind when reporters asked her tricky questions. Nevertheless, Gu’s popularity later also backfired when some felt that her comments on internet censorship in China showed how utterly unaware she was of her privileged position.

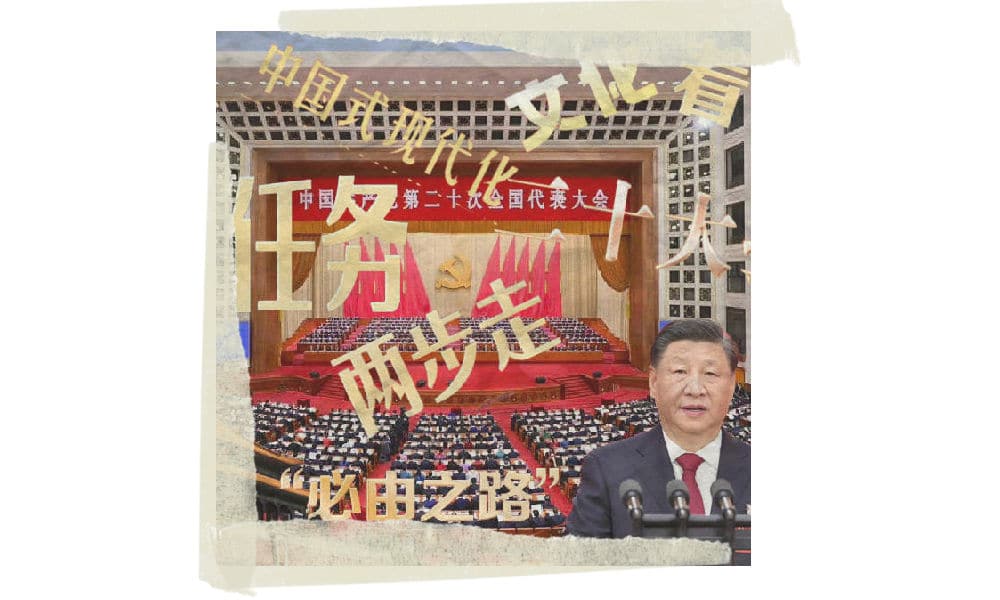

P is for: Party Congress

The 20th CPC National Congress is without a doubt one of the biggest topics in China’s 2022 online media sphere. In the weeks leading up to the event, online discussions saw stricter controls and the propaganda machine went into full swing in October of 2022 to make sure every single Chinese netizen would be aware of the main messages that were sent out to the public during the event.

Throughout his address at the opening ceremony of the Party Congress at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, Xi Jinping spoke about various issues relating to the past five years and the future of China and the Party’s mission, including the challenges faced by the Chinese people and the CPC over the past years in an increasingly “complex international situation,” explicitly mentioning the Covid-19 pandemic, the unrest in Hong Kong, and the Taiwan independence movement, emphasizing that the Chinese state and Party have managed to stand strong in hard times and are still on the journey of China’s ‘New Era’ – building China into a modern socialist country. In this context, terms such as ‘national security’ and the ‘Chinese people’ were important recurring themes (read more).

Q is for: QR Code Controversy

Since 2020, China’s Health Code apps became utterly ingrained in everyday life as a pivotal tool in the country’s ongoing fight against Covid-19. The system gave individuals colored QR codes based on their exposure risk to Covid-19 and served as an electronic ticket to enter and exit public spaces, restaurants, offices buildings, etc. Do you get a Green, Yellow, or Red QR code? That all depends on personal information, self-reported health status, Covid-19 test results, travel history, and more – the health code system operated by accessing numerous databases. The Green color means you’re safe (low-risk) and have free movement, the Yellow code (mid-risk) requires self-isolation and the Red color code is the most feared one: it means you either tested positive or are at high risk of infection. With a red code, you won’t have access to any public places and will have to go into mandatory quarantine.

In June of 2022, the story of a Henan banking scandal and depositors’ Health Codes suddenly turning red triggered online discussions in China and even made international headlines. Thousands of duped depositors who had been fighting to recover their savings came to Zhengzhou to protest and many of them saw their Health Codes turn red without any logical reason. This raised suspicions that the duped depositors were specifically targeted, and that their Health Codes were being manipulated by authorities.

“Who is in charge of changing the Health Code colors?” became a much-asked question on Weibo, with many blaming local Henan authorities for abusing their powers to try and stop protesters from raising their voices in Zhengzhou. Although Henan authorities claimed they did “not understand” what had happened, five local officials were later punished for their involvement in assigning red codes to bank depositors without authorization (read more).

R is for: Russia’s War in Ukraine

In February of 2022, a new word surfaced on Chinese social media: wū xīn gōngzuò (乌心工作), meaning people were so concerned with what was happening in Ukraine, that they could not focus on work.

At the start of the 2022 Russian invasion, most people expressed worry about the situation of the Chinese students and other Chinese citizens who were still stuck in Ukraine. There were also many anti-war messages and those siding with the victims in this conflict.

Later on, the Chinese online media discourse shifted along with a heightened international media focus on Chinese responses to the war. Within that news narrative, emphasis was placed on the role of the United States, its Western allies, and Chinese resistance against the ‘Cold War mentality’ that allegedly fueled the current crisis. Some themes were recurring in the Chinese media, where the violent conflict in Ukraine was also used to reflect on the past and future of China-West relations. In light of the recent developments, NATO’s bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade (1999) became a topic of focus again, together with discussions on what the Ukraine war could mean for Taiwan (read more).

S is for: Shinzo Abe

In the morning of July 8, 2022, Japan’s former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was shot twice during a speech for an election campaign event in the Japanese city of Nara. On Chinese social media, the incident immediately became a trending news topic and shortly after, seven of the ten top trending Weibo topics were about Shinzo Abe, with the topic “Abe Shinzo Passes Away” receiving over 1,4 billion views.

Many commenters on Chinese social media seemed to gloat over Abe’s death. Some of the comments called the shooter a ‘hero,’ saying he would not just go into Japanese history, but that he would also be remembered in Chinese history books.

Chinese commentator Hu Xijin later wrote about the difference in how Shinzo Abe is perceived in the West and in China, where he is blamed for the deterioration in Sino-Japanese relations due to his rightwing nationalist and pro-military stance, including his visits to the controversial Yasukuni Shrine during and after his time in office. Hu Xijin expressed that it was “normal” for ordinary netizens to speak their minds about Shinzo Abe, just as foreign social media users also speak their minds whenever something happens in China. Hu condemned how some foreign media allegedly used these public sentiments as if it was the Chinese standard, smearing China in doing so.

T is for: Tangshan BBQ Restaurant Violence

In June of 2022, an outburst of violence against female customers at a restaurant in Tangshan sent shockwaves across Chinese social media. Surveillance videos from the restaurant showed how at least four women were brutally attacked by a group of men. The incident, now known as the ‘6.10 Tangshan Beating Incident’ (6·10唐山打人案件) sparked national outrage and its aftermath lasted for many weeks, with people demanding more answers on what exactly happened and how authorities dealt with it.

The Tangshan incident led to online discussions about gang-related crimes. The fact that at least five of the suspects had criminal records was a cause of anger among those who felt that they should not have been allowed to be out and about at all and that they were covered by authorities.

A total of 28 people were later prosecuted for their involvement in the incident. As Hebei authorities investigated the issue, they found that some local officers protected the gangs and basically allowed them to commit more crimes by not strictly enforcing laws. At least fifteen local officials were investigated, and eight of them were later taken into custody on suspicion of abusing power, taking bribes, and forming a ‘shield’ for gang-related violence (read more).

U is for: Uncle Carpenter

2022 really needed a heart-warming story. This story about ‘Uncle Carpenter’ came just at the right time. The Chinese vlogger Yige Caixiang (衣戈猜想) posted a short film on Bilibili about his disabled uncle living in a poor rural area in China. This portrait of his resilient and resourceful ‘Uncle’ touched the hearts of many netizens, and went viral overnight.

The short video tells the story of a resilient villager who became disabled as a teenager due to medical mistakes. He was inspired to become a carpenter after seeing one at work in the family courtyard, and so he also started doing the same work, and was able to make a living by going around and doing carpentry jobs for villagers. Despite his disability, he turned out to become a crucial part of village life, with so many people depending on him.

‘Uncle Carpenter’ struck a chord with many people in difficult times. Many were inspired by the short film because of the life lessons it contains regarding perseverance and not looking back on the things that might have been different (read more).

V is for: Voices of April

Although the ‘A4 protests’ mentioned in this list might have been more visible for many in the West due to the pictures of crowds gathering in the streets, there was another kind of protest in 2022 that arguably was even bigger yet played out at a time when the streets were empty.

The ‘Voices of April’ was a video that contained edited audio snippets that showed the reality of a Covid-stricken Shanghai where residents struggled with feelings of powerlessness. The video seeped into every corner of WeChat and other social media platforms, and kept popping up in various ways despite censorship.

Voices of April told the reality of lockdown through the words of those who experienced it during the Shanghai lockdown. Food supplies going to waste due to mismanagement and failing logistics; parents and children being separated in quarantine facilities; people unsuccessfully trying to get urgent care for a medical emergency in their family; cancer patients being unable to return to their homes after getting chemotherapy at the hospital; Covid patients arriving at centralized quarantine locations that have no supplies nor beds; a desperate mother who finds herself calling out to neighbors to get medicine for her sick child in the middle of the night; pet owners in tears over their dog being killed by anti-epidemic workers.

Not long after the video went viral, Wechat and Weibo users discovered they were no longer able to forward the file, and soon all links to the video ended up leading to a ‘404’ deleted message. The censorship only added fuel to fire. “[You want] war? War it is!”, some said, with others posting images protesting the censorship: “You can’t censor the unity of the people of Shanghai!” (read more)

W is for: Want Want

You might remember the underdog brand that was a real winner in 2021 China (ERKE). In 2022, the 60-year-old Taiwanese brand Want Want – you probably know their rice crackers with the cute kid icon – become all the rage again.

In light of Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, the brand saw a revival. What really became an essential point in Want Want’s regained success this year is the brand’s consistency in delivering a patriotic message to mainland consumers through multiple channels that resonated with Chinese netizens at a time of deteriorating US-China relations and more focus on cross-strait relations.

In October of 2022, Want Want celebrated China’s National Day by using drones to project netizens’ hopes and wishes for the future all over the Great Wall, including a projection of a giant Want Want drink. Rice crackers have never been more popular (read more).

X is for: Xi’an Lockdown

What a difference twelve months make. For many living in the city of Xi’an, the New Year of 2022 did not start off bright and joyful, but dark and filled with anxiousness as millions of residents were ordered to stay at home during a lockdown amid a new wave of Covid19 infections.

During the Xi’an lockdown, Weibo saw an outpouring of anger and disbelief from sleepless netizens who expressed their shock over the way in which local authorities were managing the Covid19 outbreak and the lockdown itself. With most offline and takeout stores being closed and residents not allowed the leave their compounds, getting food supplies and other essentials became a serious problem for many.

A heartbreaking story went viral about a woman who lost her baby on January 1st when she did not receive medical care in time and was left waiting outside of the hospital, and there was an outpour of anger online from those who had been seriously impacted by the restrictions and hurdles they faced in times of a lockdown that was mismanaged by local authorities (read more).

Y is for: Yang le ge Yang

‘Sheep a Sheep’ (Yang le ge Yang 羊了个羊) is a WeChat tile-matching puzzle game that became all the rage in 2022. The rather simple game’s success became somewhat of a mystery in China, which has a vibrant online gaming market. The game’s success came at a time when people tried to avoid getting Covid, with the word for ‘turning positive’ sounding the same as ‘sheep’ (yang).

At a time of boredom, lockdowns, and a lively social media atmosphere, people become hooked on the game where players can add more sheep to their province as they go on to the next level, getting ranked based on how many sheep they have (read more about the game’s rise and fall here).

Z is for: Zero Covid: The End

We end this list with the topic that is at the center of Chinese social media trending discussions of 2022: the zero Covid policy. The ‘zero Covid strategy,’ also known as ‘dynamic zero Covid,’ is all about the speedy detection of new cases, followed by a quick response to curb the spread of the virus immediately. It was trending in early 2022 for the incredible impact it made on cities, counties, villages across China throughout 2022, and then it was trending due to the fact that the measures were changed so suddenly in December of 2022.

In October of 2022, Party newspaper People’s Daily published an article titled “Dynamic Zero Is Sustainable and Must Be Adhered To” (link), and many other media sources kept propagating this policy until a sudden policy shift.

Now, there are various views on this sudden shift. Nevertheless, many people are happy that – despite the Covid outbreaks – the era of ‘zero Covid’ with excessive measures is finally over.

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China and Covid19

Sick Kids, Worried Parents, Overcrowded Hospitals: China’s Peak Flu Season on the Way

“Besides Mycoplasma infections, cases include influenza, Covid-19, Norovirus, and Adenovirus. Heading straight to the hospital could mean entering a cesspool of viruses.”

Published

8 months agoon

November 22, 2023

In the early morning of November 21, parents are already queuing up at Xi’an Children’s Hospital with their sons and daughters. It’s not even the line for a doctor’s appointment, but rather for the removal of IV needles.

The scene was captured in a recent video, only one among many videos and images that have been making their rounds on Chinese social media these days (#凌晨的儿童医院拔针也要排队#).

One photo shows a bulletin board at a local hospital warning parents that over 700 patients are waiting in line, estimating a waiting time of more than 13 hours to see a doctor.

Another image shows children doing their homework while hooked up on an IV.

Recent discussions on Chinese social media platforms have highlighted a notable surge in flu cases. The ongoing flu season is particularly impacting children, with multiple viruses concurrently circulating and contributing to a high incidence of respiratory infections.

Among the prevalent respiratory infections affecting children are Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections, influenza, and Adenovirus infection.

The spike in flu cases has resulted in overcrowded children’s hospitals in Beijing and other Chinese cities. Parents sometimes have to wait in line for hours to get an appointment or pick up medication.

According to one reporter at Haibao News (海报新闻), there were so many patients at the Children’s Hospital of Capital Institute of Pediatrics (首都儿科研究所) on November 21st that the outpatient desk stopped accepting new patients by the afternoon. Meanwhile, 628 people were waiting in line to see a doctor at the emergency department.

Reflecting on the past few years, the current flu season marks China’s first ‘normal’ flu peak season since the outbreak of Covid-19 in late 2019 / early 2020 and the end of its stringent zero-Covid policies in December 2022. Compared to many other countries, wearing masks was also commonplace for much longer following the relaxation of Covid policies.

Hu Xijin, the well-known political commentator, noted on Weibo that this year’s flu season seems to be far worse than that of the years before. He also shared that his own granddaughter was suffering from a 40 degrees fever.

“We’re all running a fever in our home. But I didn’t dare to go to the hospital today, although I want my child to go to the hospital tomorrow. I heard waiting times are up to five hours now,” one Weibo user wrote.

“Half of the kids in my child’s class are sick now. The hospital is overflowing with people,” another person commented.

One mother described how her 7-year-old child had been running a fever for eight days already. Seeking medical attention on the first day, the initial diagnosis was a cold. As the fever persisted, daily visits to the hospital ensued, involving multiple hours for IV fluid administration.

While this account stems from a single Weibo post within a fever-advice community, it highlights a broader trend: many parents swiftly resort to hospital visits at the first signs of flu or fever. Several factors contribute to this, including a lack of General Practitioners in China, making hospitals the primary choice for medical consultations also in non-urgent cases.

There is also a strong belief in the efficacy of IV infusion therapy, whether fluid-based or containing medication, as the quickest path to recovery. Multiple factors contribute to the widespread and sometimes irrational use of IV infusions in China. Some clinics are profit-driven and see IV infusions as a way to make more money. Widespread expectations among Chinese patients that IV infusions will make them feel better also play a role, along with some physicians’ lacking knowledge of IV therapy or their uncertainty to distinguish bacterial from viral infections (read more here)

To prevent an overwhelming influx of patients to hospitals, Chinese state media, citing specialists, advise parents to seek medical attention at the hospital only for sick infants under three months old displaying clear signs of fever (with or without cough). For older children, it is recommended to consult a doctor if a high fever persists for 3 to 5 days or if there is a deterioration in respiratory symptoms. Children dealing with fever and (mild) respiratory symptoms can otherwise recover at home.

One Weibo blogger (@奶霸知道) warned parents that taking their child straight to the hospital on the first day of them getting sick could actually be a bad idea. They write:

“(..) pediatric departments are already packed with patients, and it’s not just Mycoplasma infections anymore. Cases include influenza, Covid-19, Norovirus, and Adenovirus. And then, of course, those with bad luck are cross-infected with multiple viruses at the same time, leading to endless cycles. Therefore, if your child experiences mild coughing or a slight fever, consider observing at home first. Heading straight to the hospital could mean entering a cesspool of viruses.”

The hashtag for “fever” saw over 350 million clicks on Weibo within one day on November 22.

Meanwhile, there are also other ongoing discussions on Weibo surrounding the current flu season. One topic revolves around whether children should continue doing their homework while receiving IV fluids in the hospital. Some hospitals have designated special desks and study areas for children.

Although some commenters commend the hospitals for being so considerate, others also remind the parents not to pressure their kids too much and to let them rest when they are not feeling well.

Opinions vary: although some on Chinese social media say it's very thoughtful for hospitals to set up areas where kids can study and read, others blame parents for pressuring their kids to do homework at the hospital instead of resting when not feeling well. pic.twitter.com/gnQD9tFW2c

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) November 22, 2023

By Manya Koetse, with contributions from Miranda Barnes

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China and Covid19

Repurposing China’s Abandoned Nucleic Acid Booths: 10 Innovative Transformations

Abandoned nucleic acid booths are getting a second life through these new initiatives.

Published

1 year agoon

May 19, 2023

During the pandemic, nucleic acid testing booths in Chinese cities were primarily focused on maintaining physical distance. Now, empty booths are being repurposed to bring people together, serving as new spaces to serve the community and promote social engagement.

Just months ago, nucleic acid testing booths were the most lively spots of some Chinese cities. During the 2022 Shanghai summer, for example, there were massive queues in front of the city’s nucleic acid booths, as people needed a negative PCR test no older than 72 hours for accessing public transport, going to work, or visiting markets and malls.

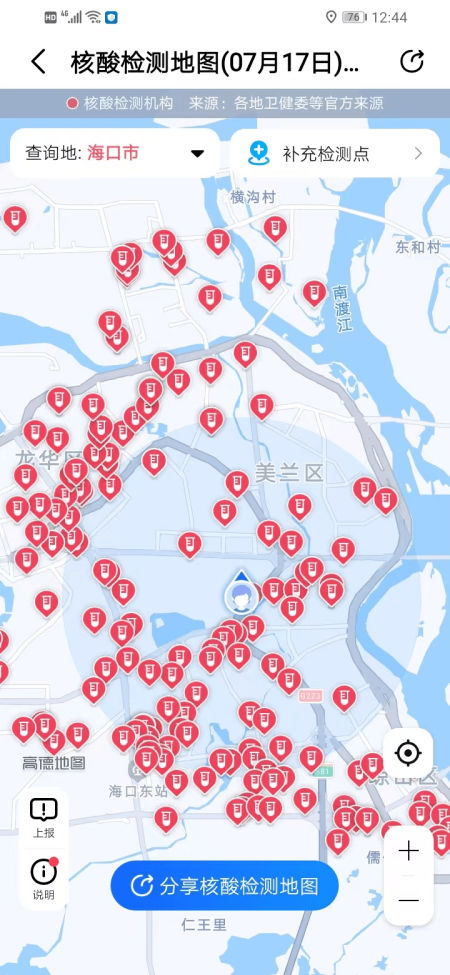

The word ‘hésuān tíng‘ (核酸亭), nucleic acid booth (also:核酸采样小屋), became a part of China’s pandemic lexicon, just like hésuān dìtú (核酸地图), the nucleic acid test map lauched in May 2022 that would show where you can get a nucleic test.

Example of nucleic acid test map.

During Halloween parties in Shanghai in 2022, some people even came dressed up as nucleic test booths – although local authorities could not appreciate the creative costume.

Halloween 2022: dressed up as nucliec acid booths. Via @manyapan twitter.

In December 2022, along with the announced changed rules in China’s ‘zero Covid’ approach, nucleic acid booths were suddenly left dismantled and empty.

With many cities spending millions to set up these booths in central locations, the question soon arose: what should they do with the abandoned booths?

This question also relates to who actually owns them, since the ownership is mixed. Some booths were purchased by authorities, others were bought by companies, and there are also local communities owning their own testing booths. Depending on the contracts and legal implications, not all booths are able to get a new function or be removed yet (Worker’s Daily).

In Tianjin, a total of 266 nucleic acid booths located in Jinghai District were listed for public acquisition earlier this month, and they were acquired for 4.78 million yuan (US$683.300) by a local food and beverage company which will transform the booths into convenience service points, selling snacks or providing other services.

Tianjin is not the only city where old nucleic acid testing booths are being repurposed. While some booths have been discarded, some companies and/or local governments – in cooperation with local communities – have demonstrated creativity by transforming the booths into new landmarks. Since the start of 2023, different cities and districts across China have already begun to repurpose testing booths. Here, we will explore ten different way in which China’s abandoned nucleic test booths get a second chance at a meaningful existence.

1: Pharmacy/Medical Booths

Via ‘copyquan’ republished on Sohu.

Blogger ‘copyquan’ recently explored various ways in which abandoned PCR testing points are being repurposed.

One way in which they are used is as small pharmacies or as medical service points for local residents (居民医疗点). Alleviating the strain on hospitals and pharmacies, this was one of the earliest ways in which the booths were repurposed back in December of 2022 and January of 2023.

Chongqing, Tianjin, and Suzhou were among earlier cities where some testing booths were transformed into convenient medical facilities.

2: Market Stalls

In Suzhou, Jiangsu province, the local government transformed vacant nucleic acid booths into market stalls for the Spring Festival in January 2022, offering them free of charge to businesses to sell local products, snacks, and traditional New Year goods.

The idea was not just meant as a way for small businesses to conveniently sell to local residents, it was also meant as a way to attract more shoppers and promote other businesses in the neighborhood.

3: Community Service Center

Small grid community center in Shizhuang Village, image via Sohu.

Some residential areas have transformed their local nucleic acid testing booths into community service centers, offering all kinds of convenient services to neighborhood residents.

These little station are called wǎnggé yìzhàn (网格驿站) or “grid service stations,” and they can serve as small community centers where residents can get various kinds of care and support.

4: “Refuel” Stations

In February of this year, 100 idle nucleic acid sampling booths were transformed into so-called “Rider Refuel Stations” (骑士加油站) in Zhejiang’s Pinghu. Although it initially sounds like a place where delivery riders can fill up their fuel tanks, it is actually meant as a place where they themselves can recharge.

Delivery riders and other outdoor workers can come to the ‘refuel’ station to drink some water or tea, warm their hands, warm up some food and take a quick nap.

5: Free Libraries

image via sohu.

In various Chinese cities, abandoned nucleic acid booths have been transformed into little free libraries where people can grab some books to read, donate or return other books, and sit down for some reading.

Changzhou is one of the places where you’ll find such “drifting bookstores” (漂流书屋) (see video), but similar initiatives have also been launched in other places, including Suzhou.

6: Study Space

Photos via Copyquan’s article on Sohu.

Another innovative way in which old testing points are being repurposed is by turning them into places where students can sit together to study. The so-called “Let’s Study Space” (一间习吧), fully airconditioned, are opened from 8 in the morning until 22:00 at night.

Students – or any citizens who would like a nice place to study – can make online reservations with their ID cards and scan a QR code to enter the study rooms.

There are currently ten study booths in Anji, and the popular project is an initiative by the Anji County Library in Zhejiang (see video).

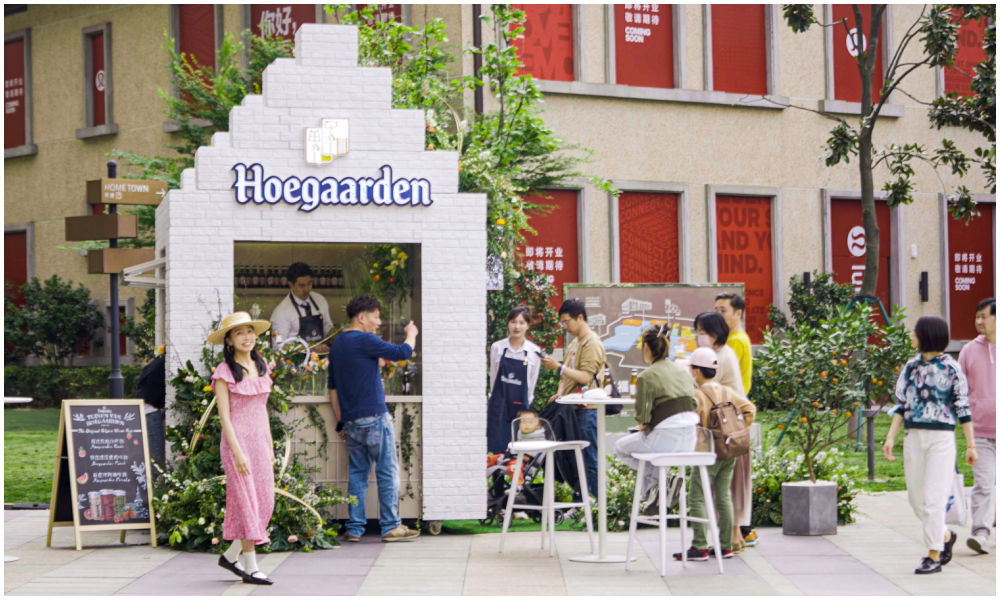

7: Beer Kiosk

Hoegaarden beer shop, image via Creative Adquan.

Changing an old nucleic acid testing booth into a beer bar is a marketing initiative by the Shanghai McCann ad agency for the Belgium beer brand Hoegaarden.

The idea behind the bar is to celebrate a new spring after the pandemic. The ad agency has revamped a total of six formr nucleic acid booths into small Hoegaarden ‘beer gardens.’

8: Police Box

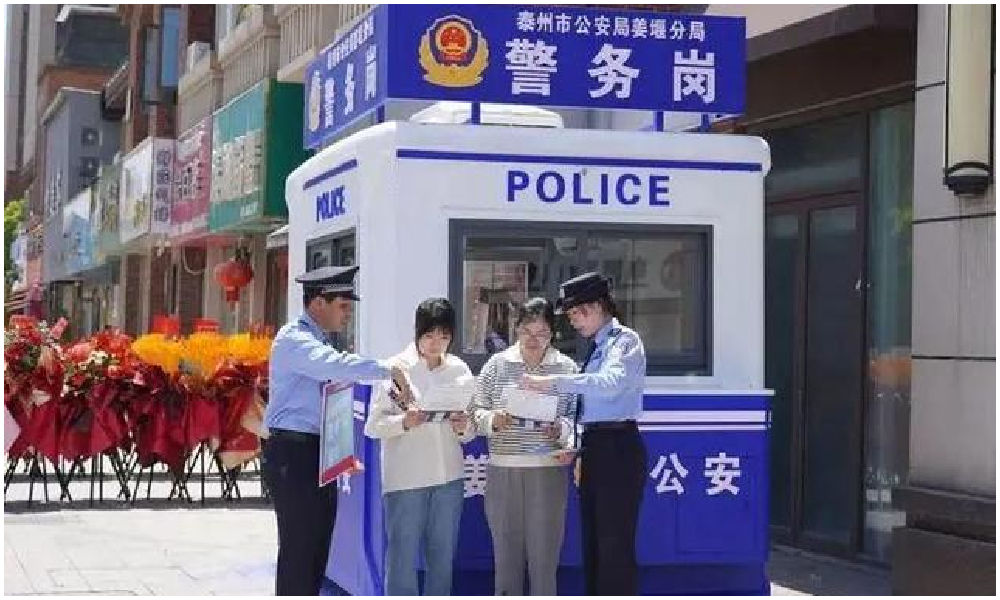

In Taizhou City, Jiangsu Province, authorities have repurposed old testing booths and transformed them into ‘police boxes’ (警务岗亭) to enhance security and improve the visibility of city police among the public.

Currently, a total of eight vacant nucleic acid booths have been renovated into modern police stations, serving as key points for police presence and interaction with the community.

9: Lottery Ticket Booths

Image via The Paper

Some nucleic acid booths have now been turned into small shops selling lottery tickets for the China Welfare Lottery. One such place turning the kiosks into lottery shops is Songjiang in Shanghai.

Using the booths like this is a win-win situation: they are placed in central locations so it is more convenient for locals to get their lottery tickets, and on the other hand, the sales also help the community, as the profits are used for welfare projects, including care for the elderly.

10: Mini Fire Stations

Micro fire stations, images via ZjNews.

Some communities decided that it would be useful to repurpose the testing points and turn them into mini fire kiosks, just allowing enough space for the necessary equipment to quickly respond to fire emergencies.

Want to read more about the end of ‘zero Covid’ in China? Check our other articles here.

By Manya Koetse,

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?