Chinese New Year

Single Female Blogger Dreads Parental Pressure, Collects Stories to Highlight Dangers of Rushing into Marriage

A recent initiative by a Weibo blogger aims to prove that nothing good comes from marriage pressure.

Published

5 years agoon

First published

Rushed marriages may not end well, so do not pressure your child to get married – this is the message one so-called “leftover woman” wants to get out there, as she has been collecting the stories of women who rushed into marriage as a result of family pressure.

It is a recurring topic every year when Chinese New Year is about to start: the pressure China’s bachelors and bachelorettes face when they return home to spend time with their families, who will inevitably ask them when they will settle down and get married.

This pressure is especially real for China’s unmarried daughters; those who are single in their late twenties and early thirties are soon labeled as ‘leftover women’ (剩女 shèngnǚ), which became a catchphrase ever since the Chinese Ministry of Education listed it as one of the newest additions to the Chinese vocabulary in 2007.

The shengnü label is mainly applied to unmarried (urban) women in their late twenties or early thirties who are generally well-educated and goal-oriented, but who came to be associated with ‘leftover food’ because of their single status and long-standing prevailing beliefs about the right age to marry.

One 2015 survey by Chinese dating site ‘Zhenai’ showed that 50% of Chinese men think that women who are still single at the age of 25 are ‘leftovers,’ and many Chinese parents urge their daughters to get married before that happens.

“She returned home to visit her parents, and then committed suicide there by jumping off a building.”

This year, some single ladies, while planning their upcoming trip to their hometowns to celebrate the Spring Festival, are already mentally preparing for the nagging questions they will be confronted with once they come home.

One of them is the Chinese blogger nicknamed ‘Little Deer-Loving Forest’ (@爱麋鹿的小森林), who recently asked her followers for help in convincing her relatives that nothing good comes from rushing into marriage; she asked them to share the (news) stories of women who were pushed to get married, and then experienced hardships and suffering because of it.

By mid-January, within three days after she first posted her request, Weibo users had already shared dozens of news links and stories detailing the horrific accounts of women who had married to escape the pressure put on them by their families. By now, the blogger’s post itself has been reposted nearly 70,000 times.

One of the many stories was that of a young woman in Linquan county in Fuyuan, who attempted to commit suicide in the summer of 2018 after being pressured into marriage. The woman was so burdened by the pressure she faced, that she had jumped into a river. A bystander was able to alert the authorities, who were able to rescue her.

Some also share stories from their own social circles, with one commenter from Guangdong writing that a friend of her friend was also pushed to get married: “He had money, a house, and a car, but he was working night shifts in a convenience store. Turned out he was actually gay and that she ended up in a ‘fake marriage.'”

“A girl in my hometown was in her thirties and single. Her parents insisted she had to marry a man who had been married before [it was his second marriage]. I’m not sure if it was three weeks or three months after the wedding, but she returned home to visit her parents, and then committed suicide there by jumping off a building. Don’t blindly get married.”

“You are all my comrades in this campaign!”

‘Little Deer’ shared her plans on keeping a collection of these stories to post on her ‘WeChat Moments’ page every day during the Chinese New Year, to show her family what could potentially happen when women are rushed into marriage.

Many commenters praised the blogger’s initiative, writing: “I need to save this post!! It’ll be very useful during Chinese New Year!” “Exactly what I needed, thank you, everyone! You are all my comrades in this campaign, I feel very supported with all of you out there. Let’s go square dancing together when we are old!”

Others, however, were less enthusiastic and pointed out that they had tried this method before, but that their parents weren’t buying it, saying that these type of “irrelevant stories” had “nothing to do with them.”

Single men also joined the debate with many requesting the original poster to gather news stories detailing the negative outcomes for men who had been pressured to get married.

One of these stories is that of a 26-year-old man from Wuhan, who was diagnosed with severe depression after his mother had continuously urged him to marry.

By now, Little Deer’s post has also inspired people to discuss other subjects involving family pressure, asking: “Are there any stories about being pushed to have kids?” This request led to some expressing concerns about the post itself being censored: “Will this be deleted by Sina, as it’s against our current national policy of encouraging people to get married and have kids?”

“Why are you sending me these useless things?”

In early 2019, China launched a new ‘Individual Income‘ tax deduction method, which, among other things, allows children’s education expenses to be deducted before tax. Because those who are unmarried and without children will pay relatively more taxes, these parts of the personal income tax have been nicknamed ‘single’s tax’ (单身税) and ‘no children’s tax’ (不孕不育税) on social media.

These measures, along with other examples (such as the cancellation of the ‘late marriage leave‘), show the government’s efforts to combat China’s dropping birthrates, indirectly encouraging people to get married and have children.

According to a report released by the Ministry of Civil Affairs in 2018, marriage registration numbers have been dropping in China, showing that more people are putting off marriage or are getting married at a later age – something that is especially visible in the 30-34 age group.

Some analysts believe that a higher level of education and the rising cost of living have contributed to the tendency to marry and have children at a later age.

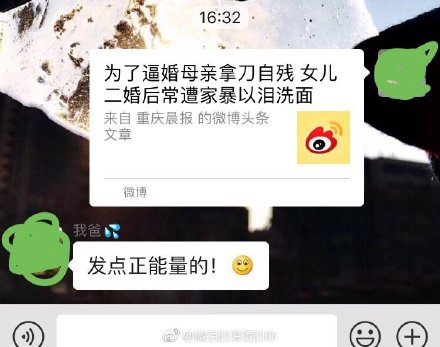

For now, it is not clear if the blogger’s initiative is actually effective for those dreading going home for Chinese New Year. Dozens of commenters are posting their parents’ reaction upon sending them the links to the unfortunate stories of those who were rushed into marriage. “Why are you sending me these useless things,” some parents said, with another chat screenshot showing a parent writing: “Send me something positive!”

By Miranda Barnes and Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know through email.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Miranda Barnes is a Chinese blogger and part-time translator with a strong interest in Chinese media and culture. Born in Shenyang, she used to work and live in Beijing and is now based in London. On www.abearandapig.com she shares news of her travels around Europe and Asia with her husband.

Also Read

Chinese New Year

Weibo Watch: Stealing the Show

About the biggest controversy surrounding the 2024 Spring Festival Gala, ‘Chunshan Studies’, Jia Ling’s peak in popularity, and other must-know Weibo topics.

Published

5 months agoon

February 20, 2024

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #24

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Stealing the show

◼︎ 2. What’s Been Trending – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What More to Know – Five bit-sized trends

◼︎ 4. What’s the Drama – Top TV to watch

◼︎ 5. What Lies Behind – Celebrations and frustrations

◼︎ 6. What’s Noteworthy – Fu Yuanhui’s plea for help

◼︎ 7. What’s Popular – Multi-talented Jia Ling’s peak in popularity

◼︎ 8. What’s Memorable – The micro-film of the Spring Festival

◼︎ 9. Weibo Word of the Week – “Chunshan Studies”

Dear Reader,

It has been several years since I officially paused my PhD studies to dedicate my full attention to What’s on Weibo. My research focus during my studies was centered on the representation of the Second Sino-Japanese War in Chinese and Japanese popular culture, a topic I still find fascinating and relevant. However, one problem I encountered while doing my PhD was the constant allure of equally fascinating trends or topics to explore. The Spring Festival Gala is one such topic that always ranked high on my ‘PhD research wishlist.’

I’m sure you’re all familiar with the Gala by now, but just to recap: the CMG Spring Festival Gala, formerly known as the CCTV Spring Festival Gala, is the state media’s annual live television event broadcasted on the evening of Chinese New Year since 1983. It’s one of the most-watched variety shows globally, attracting an average of 700 million viewers. Over 679 million people tuned in to the live broadcast this year (by comparison, the latest Super Bowl had a viewership of 123 million). The Gala features various acts, including singing, dancing, and comedy, spanning approximately 4 hours.

The Gala holds immense significance for all involved parties, from production teams to performers and sponsors. It’s a convergence of culture and commerce, where the Party meets pop culture. CMG (China Media Group), under the direct control of the Central Propaganda Department of the Communist Party, utilizes the show to communicate official ideology, promote traditional culture, and showcase top national performers. Despite its commercial aspect, the Gala always remains highly political, blending official propaganda with entertainment. Over the years, it has also become a platform to showcase China’s innovative digital technologies.

Given its importance, it’s not surprising that every second of the show is closely examined, analyzed, scrutinized by an audience of millions. This also results in a new controversy surrounding the show virtually every year, whether it’s about a performance that is deemed racist or about jokes that are believed to be sexist, about who appeared and who did not come up, about magic tricks going wrong or an audience member caught on camera while picking their nose.

The controversy you need to know about this year concerns Chinese actor Bai Jingting (白敬亭). Together with Wei Chen (魏晨) and Wei Daxun (魏大勋), he performed the song “Going Up Spring Mountain” (上春山). Although the song itself initially wasn’t particularly noteworthy, the performance attracted major attention due to the positioning of the three singers on a tiered platform, representing a mountain, with Bai standing on the highest pedestal. After Bai sang his part of the song, it seemed like he was supposed to step down but he didn’t, so Wei Daxun sang from a lower step afterward. It was rumored that Bai Jingting may have intentionally vied for a more prominent position to attract more attention on stage, resulting in choreographic asymmetry and some apparent confusion among the performers.

Adding fuel to these rumors is the fact that Bai was the only performer wearing all black, while the other two wore white. After rehearsal videos of the performance were posted online, netizens noticed that in one video Bai initially stepped down after singing his part, and that he also wore white in another. This led to claims that Bai purposely changed his outfit last-minute to black, so that he could ‘steal the show’ while occupying the center position. It would also make it impossible for producers to switch to a rehearsed version of the song. (Although it’s a live show, every year’s Gala has a taped version of the full dress rehearsal that runs together with the live broadcast, so that in the event of a problem or disruption, the producers can seamlessly switch to the taped version without TV audiences noticing anything. A change in position or attire would make this impossible.)

While these are all mere rumors, they triggered widespread criticism of Bai, trending throughout the week. People accused him of having a bad character and wanting to steal the limelight, it even sparked the new term ‘Chunshan Studies’ (see our Weibo Word of the Week) and the video of “Going Up Spring Mountain” (上春山) became the Gala most replayed performance. The title ““Going Up Spring Mountain” took on an entirely different meaning and was even trademarked by a company in Shenzhen. It sparked memes, jokes, and led to people mimicking the song or editing images of the performance.

CCTV made it clear in a popular Weibo hashtag that “Every move in the Spring Festival Gala is carefully designed and precisely presented” (#春晚每一个走位都精心设计并被准确呈现#), suggesting Bai followed directorial instructions and never sought the limelight. It’s quite ironic that while the Gala usually wants to pretend that there is still some spontaneity involved, it now had to stress how there actually is none whatsoever to protect Bai’s reputation.

Also ironic is that while the entire discussion revolved around whether or not Bai was stealing the show, the song “Going Up Spring Mountain” actually did steal the spotlight and became the most-discussed act of the night. This year’s controversy adds to the Gala’s long list of noteworthy moments, each shedding light on the changing dynamics of China’s evolving media landscape, propaganda efforts, nationalism, gender issues, fan culture, and more. Perhaps it’s time for someone to undertake a PhD on that…

Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang contributed to this Weibo Watch newsletter.

Best,

Manya (@manyapan)

PS Is there a China Studies topic that’s on your ‘wishlist’ too? Or have you come across any new trends or online phenomena that piqued your interest? I’m always eager to learn more about what fascinates you. Don’t hesitate to shoot me a message!

What’s Been Trending

1: The CMG Gala | The CMG Spring Festival Gala is not just an essential part of Chinese Lunar New Year celebrations, it is also the biggest televised media spectacle of the year. Over the entire last week, this four-hour extravaganza featuring forty-six performances has dominated social media conversations. In this article, we reflect on the highs and lows of this year’s edition of the world’s most-watched television program. Read all about it here 👇🏼

2: What a Mess | In the summer of 2023, it seemed like Messi’s popularity in China had reached its peak during a friendly match between Argentina and Australia held at Beijing’s Workers’ Stadium when a Chinese fan stormed onto the pitch and embraced Messi. The incident went viral and only garnered more appreciation for the soccer superstar, who extended his arms and reciprocated the hug. Fast forward eight months, and Messi’s reputation in China has plummeted to its lowest point. His highly anticipated appearance in a match in Hong Kong failed to materialize, leaving fans and organizers disappointed. Many suspect political motivations behind his absence, leading to widespread disillusionment among Chinese fans. (Updated with Messi’s response on 2/19).

3: Box Office Peak Season | During the Chinese Spring Festival, along with the National Day Holiday, movies tend to earn around 32.3% more on average. Sci-fi and action films are usually the most successful, followed by comedies. Last year, the Spring Festival box office revenues accounted for about 12.3 percent of the yearly total. This year, it was actually all about comedy and animation. Jia Ling’s latest movie was the most anticipated one. Check the big nine Spring Festival movies in our article below.

What More to Know

◼︎ 🚙 Long Way Home | Sold-out tickets, overcrowded trains, traffic jams, and aggravated travelers – the Chinese New Year travel season has been a hot topic on Chinese social media recently, sparking various discussions. Over the weekend of February 17-18, terms such as ‘way home’ (返程) and ‘traffic jam’ (堵车) dominated Weibo as the eight-day Spring Festival holiday ended, with millions returning home after leisure travel and family visits. The situation was particularly severe in Hainan, where some endured waits of up to fourteen hours for a ferry, despite local authorities predicting a seven-hour clearance for traffic jams. China Daily reported that the provincial government increased the number of flights and ferries in hopes of avoiding mass congestion, but to no avail. As people nationwide faced difficulties returning home by train, boat, or car, more voices on social media called for amendments to the annual leave and public holiday system, advocating for a more staggered return to work to alleviate nationwide travel congestion (related Weibo hashtag: #海南离岛严重拥堵有人排14小时上船#, 130 million views).

◼︎ 👫 Holding Hand Gate Continued | Remember the 2023 so-called ‘Holding Hand Gate’? Chinese social media exploded after a local SOE official was snapped by a street photographer while taking a stroll with his mistress, a co-worker who had joined him on a Chengdu business trip. The viral video showed the woman elegantly dressed in a fitted pink ensemble, adorned with a $5000 Dior purse, walking hand in hand with the official, who sported a coordinated t-shirt and carried shopping bags. The man, PetroChina executive Hu Jiyong, was fired after his extramarital affair was exposed online. The woman, PetroChina employee Ms. Dong, was also dismissed. Now, the affair has again gone trending after Ms. Dong talked about the aftermath in a February 18 Douyin livestream, calling the commotion surrounding the exposed affair a particularly dark moment in her life, which she got through thanks to the help of her loved ones. However, the livestream was cut off halfway and the account was suspended for “violating the platform’s relevant regulations” (related Weibo hashtag #太古里牵手门女当事人直播间被封#, 270 million views).

◼︎ 🤖 OpenAI’s Sora | Since the American AI research company OpenAI introduced its new video generation model ‘Sora’ on February 16, it has become a big topic of discussion in Chinese media and on Weibo. Though not officially launched yet, demo videos released by Sora show what the new text-to-video model is capable of, allowing users to create very realistic, high-quality and detailed videos. In a recent column, Chinese political commenter Hu Xijin called Sora a “groundbreaking development” while also expressing worries over how these new technologies will impact the future of realistic film and the film industry at large. At the same time, Hu also wondered what the rapid progress of American AI companies means for China and its AI ambitions, calling the introduction of Sora a “warning” that China may be lagging behind when it comes to AI. If you’re interested to read more on this, I recently wrote an op-ed for The Guardian about the US-China race for AI supremacy: link. (Related Weibo hashtag #OpenAI首个视频生成模型Sora有多强大#, 28 million views).

◼︎ 🇷🇺 Navalny’s Death | The death of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny shocked the world this week. The 47-year-old anti-corruption activist died in a maximum-security prison in Russia’s far north. A day before his death was announced, Navalny appeared in a court hearing, where he cracked jokes about needing money from the judge. In the years leading up to his death, Navalny endured chemical burns and survived poisoning attempts. In a video message, Navalny’s wife, Yulia Navalnaya, held Putin accountable for her husband’s death. Chinese state media outlets reported Navalny’s death on Weibo, citing Russian statements that he suddenly fell ill after a walk in the prison on Friday, leading to shock and eventual passing. On Weibo, some commenters cynically dubbed his death as “Russia-style modernization,” while others criticized it as “Putin’s way,” labeling Putin as a ‘Czar’ or ‘Emperor.’ There were also remarks suggesting that Navalny’s demise was the foreseeable consequence of Russia’s intolerance toward opposition, and wrote that Navalny himself had opted to return to Russia after being treated in Germany in 2021 (related Weibo hashtag #俄反对派人士纳瓦利内狱中死亡#, 27 million views).

◼︎ 🦒 Giraffes on Weibo| Since I missed one newsletter edition (following the late little rabbit news), I haven’t had the chance to cover the giraffe incident on Weibo yet. Here’s a brief overview: In early February, around the 3rd, Weibo users flooded the US embassy’s account page with complaints about their economic struggles and plummeting stock market worries. The post they were responding to wasn’t related to China’s economy at all; it was about tracking giraffes in Namibia using GPS technology. This seemingly innocent post became a platform for discussing China’s post-pandemic economic issues and also included direct criticism of Chinese leadership. It’s not uncommon for Chinese netizens to use seemingly unrelated hashtags or posts to discuss sensitive topics, hoping to evade censorship. However, the giraffe thread was eventually censored anyway. Despite this, the post still garnered over 20,000 shares and nearly a million likes. Who would’ve thought wildlife conservation could be so popular? 🤡

What’s the Drama

The TV drama “Amidst a Snowstorm of Love” (在暴雪时分) currently ranks number one on Weibo and Baidu’s Top TV drama rankings. The romantic drama tells the love story of snooker player Lin Yiyang (林亦扬, played by Wu Lei 吴磊) and nine-ball player Yin Guo (殷果, played by Zhao Jinmai 赵今麦). It is a genuine love story that showcases the chemistry between the two main stars, and the high ratings for the drama show that audiences were craving a straightforward drama that warms hearts on cold days. The drama premiered on February 2 and has since skyrocketed in popularity. The main hashtag on Weibo has received over 4 billion clicks, with 150 million views on February 19 alone.

▶️ This drama is an adaptation of the novel “Amidst a Snowstorm of Love” (在暴雪时分) by Chinese web novelist and screenwriter Mobao Feibao (墨宝非宝).

▶️ Singer Deng Dian (邓典D.D, b. 1999) performed the theme song for this drama, which has also become an online hit.

▶️ To realistically portray his characters, actor Wu Lei underwent snooker and billiards training before filming the drama. He also learned horse riding, archery, badminton, and tennis for other roles, leading some commentators to joke that he’s getting ready to compete in the “Olympics” of China’s entertainment industry.

You can watch Amidst a Snowstorm of Love with English subtitles via Viki here.

What Lies Behind

Only a few days into the Chinese New Year, China had already registered over 3.5 billion passenger trips. The Spring Festival travel rush is known as the world’s largest annual migration, predominantly journeys back to hometowns and family reunions. And so, over the past ten days or so, social media was flooded with videos showing family members’ emotional reactions when they are surprised by the homecoming of loved ones. Videos showed tears, laughter, hugs, and gentle scoldings for not giving advance notice of arrivals. Many viewers admitted to being moved to tears by these heartfelt moments while scrolling on their phones. But during the Spring Festival, we gradually saw a shift in people’s posts as they reported from their hometowns, where happy family reunions often turned into dinner dramas.

Returning home after prolonged separation from parents often evokes mixed feelings among Chinese younger people. While they look forward to family gatherings and homemade comfort food, they also worry that their family might find out that the idealized portrayal of their lives over the phone doesnt exactly match the reality. The joy of reunion fades with each passing day.

“It’s my fourth day home and I’ve been offering to do all the dishes to nurture our family bond,” some said, “but now, on day five, an argument has finally broke out.” While the immediate triggers for family disputes may vary, underlying reasons are often similar, as shared by Weibo users. Comments like “All you do is stay glued to your phone,” “You can’t even support yourself with your income; do you know how much money your cousin is making?” and “When are you getting married? You’re embarrassing us,” are commonplace. One commenter lamented, “I’m currently locked up in my room after a disagreement with my family. They all say home is a safe haven, but we all know that returning home during Chinese New Year means stepping into the eye of a storm.”

Amid these challenging times, psychologists offer online tips to foster better understanding of the generation gap and improve communication. Nevertheless, many express the difficulty of engaging in equal and respectful conversations with their parents and elders. As one blogger reflected, “It’s always the same emotional cycle during the Spring Festival: a honeymoon phase to start with, followed by numerous arguments, and sadness upon leaving home in the end.”

What’s Noteworthy

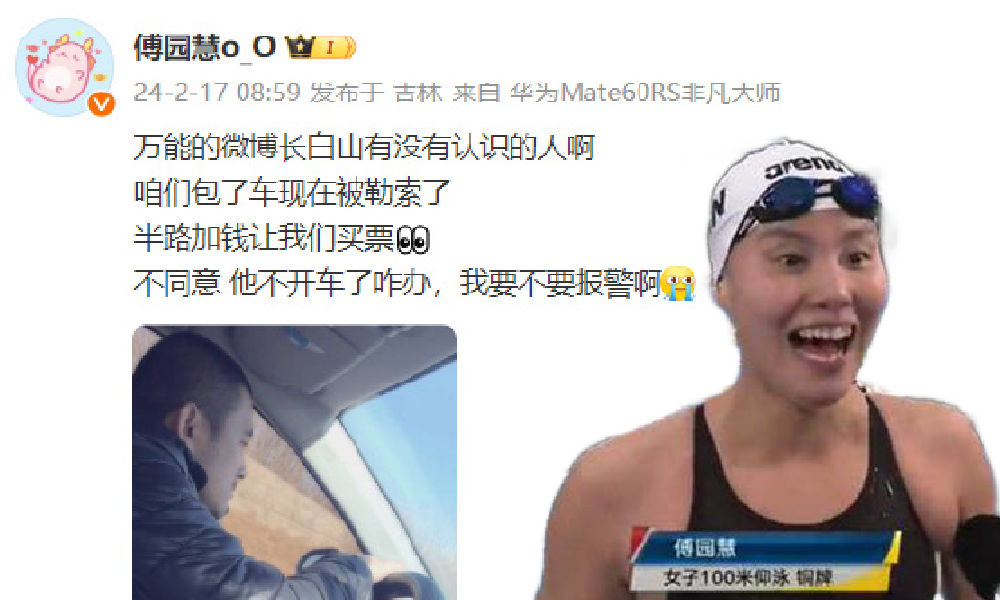

“We hired a car and now we’re being extorted. Halfway through, they wanted us to pay more to buy tickets; we disagreed, so now the driver won’t continue driving. What should I do? Should I call the police?” This was the urgent plea for help that Olympic swimmer Fu Yuanhui (傅园慧) posted on Weibo on Saturday morning, February 17th. Following her post, Fu Yuanhui and the scamming incident quickly went trending on Weibo, and her situation was soon resolved. This also led to criticism, as people argued she only got help so quickly because she is famous. Read more via link below.

What’s Popular

So far, the Year of the Dragon is an especially fruitful one for Chinese actress and director Jia Ling (贾玲). Although the famous comedian had previous major successes with her directorial debut Hi, Mom in 2021, her current popularity is unprecedented: everyone is talking about Jia Ling.

We recently covered Jia Ling’s return to the spotlight after a year-long break from the public eye. Not only did she announce her new film YOLO (热辣滚烫), the actress also lost a staggering 110 lbs (50 kg) for her role.

Her movie turned out to be the biggest box office hit of the season. Of all the different box office premieres during the eight-day Spring Festival holiday, Jia Ling’s YOLO took the lead with 2.7 billion yuan.

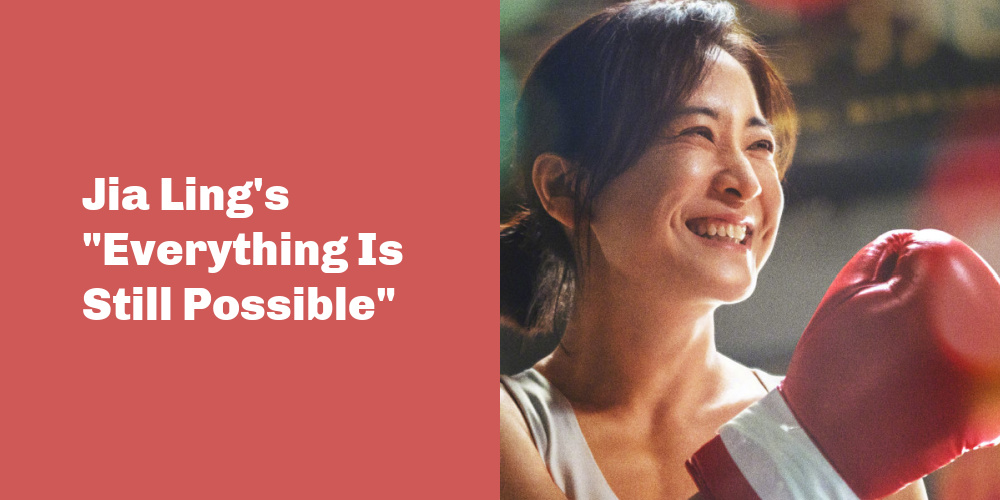

YOLO (热辣滚烫) is an inspirational story about an overweight woman who finds new purpose and becomes fit through boxing. But it’s about more than the movie alone: Jia Ling herself has become a great source of inspiration to others. Besides acting and directing, she is now also singing and composing. This week, the music video for Jia’s song “Everything Is Still Possible” or “Everything Comes in Time” (一切都来得及) was released. In the video, the ‘new’ Jia Ling can be seen singing a duet with her former self, singing about the importance of loving yourself.

Jia Ling singing a duet with her old self.

After her box office success, hit song, and new appearance, it seems that Jia Ling is at the peak of her popularity. She’s become a role model for her talent, dedication, and style – she’s the hottest woman on Weibo.

What’s Memorable

In light of the Spring Festival, we’ve picked this article from our archive from one year ago which explores a new genre that was introduced during the CMG Gala in 2023, namely the ‘micro film.’ While this year’s show also featured another short film by director Zhang Dapeng at the very beginning, the 2023 short film titled “Me and My Spring Festival Night” (“我和我的春晚”) truly captivated audiences. This 7-minute mini-film was a remarkable piece of storytelling with a surprising twist at the end. Many viewers hailed it as the highlight of the Gala, with some even going so far as to call it the best segment of the Gala they’d seen in a decade. Read more about the short film here 👇

Weibo Word of the Week

“Chunshan Studies” | Our Weibo Word of the Week is “Spring Mountain Studies” or “Chunshan Studies” (Chūn Shān Xué 春山学), a phrase which has taken the Chinese internet by storm recently.

“Chunshan Studies” emerged as a result of the controversy surrounding the song “Going Up Spring Mountain” performed at the annual CMG Spring Festival by Bai Jingting (白敬亭), Wei Chen (魏晨), and Wei Daxun (魏大勋). Bai, the only singer of the three dressed in black and standing at the highest pedestal during the live performance, became the subject of online scrutiny when netizens accused him of purposely choosing his position and attire to steal the spotlight.

The incident became a hot topic, almost evolving into a full-fledged study with various related theories, hence netizens humorously started referring to it as “Spring Mountain Studies” or “Chunshan Studies”. Netizens meticulously scrutinized everything from wardrobe details to body language, searching for hidden meanings and subtle clues that may reveal the intentions of those involved and the truth of what happened on stage. On social media platforms Douyin and Bilibili, numerous “Chunshan Studies” videos emerged, providing frame-to-frame analyses of how Bai Jingting may have tried to seize the main position and supposed abnormal stage movements.

Chunshan Studies has become a distinct field of study focusing on the “Going Up Spring Mountain” controversy, but it also intersects with critical analysis, popular media discourse, and social studies. Some commenters believe that the discussions about Bai Jingting’s position on stage are actually about equity and ethical behavior.

Guess we all learned something new this Spring Festival!

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

China Travel

Olympic Swimming Fu Yuanhui Gets Help via Weibo Following Taxi Scam

Olympic champion Fu Yuanhui, known for her ‘mystical powers,’ turned to social media when she faced a tourist scam.

Published

5 months agoon

February 17, 2024

“We hired a car and now we’re being extorted. Halfway through, they wanted us to pay more to buy tickets; we disagreed, so now the driver won’t continue driving. What should I do? Should I call the police?”

This was the plea for help that Olympic swimmer Fu Yuanhui (傅园慧) posted on Weibo on Saturday morning, February 17. The popular athlete informed her followers that she was around the Changbai Mountain Scenic Area, a popular winter tourist destination in China’s Jilin Province, when her driver suddenly demanded more money from her.

Shortly after posting about her predicament, Fu Yuanhui sent out an update: “Thank you all for following, the Jilin Ministry of Culture and Tourism swiftly stepped in, the problem is already solved now. Thanks everyone.”

Following these posts, Fu Yuanhui and the Changbai incident quickly went trending on Weibo, where many people commented that her situation was only resolved so quickly because she is famous.

Fu Yuanhui became a Chinese internet sensation eight years ago, after her performance and interviews during the Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. When talking to reporters, Fu was excited, positive, and refreshingly honest. She introduced the popular phrase “mystical powers” (洪荒之力, literally: power strong enough to change the universe) when explaining that she was swimming extra fast because she was “using all ‘mystical powers'” (read more). She also went viral for expressing genuine delight upon discovering she had won a bronze medal, and for disclosing that she did not swim very well another time because she was on her period.

Fu Yuanhui charmed Chinese audiences after her disarming interviews during the Summer Olympics in 2016.

Following her Olympic success, Fu gained many fans on social media. On Weibo, she has over 7 million followers.

It is clear that her fame and relatively large following played a role in how fast her issue was resolved. Not only did the local authorities step in, the driver who extorted her reportedly was also quickly punished for his actions and received a 30,000 yuan fine (US$4215). A related hashtag, published by state media outlet CCTV, went viral and received over 130 million views on Weibo (#对傅园慧加价黑车司机被罚3万元#).

While most are glad to see the driver get punished so soon, many commenters argue that it’s unfair for someone like Fu Yuanhui to receive swift assistance while many ordinary travelers across China facing scams during this holiday season struggle to get the help they need.

On February 16, a Chinese family of five was kicked off a tour bus during their trip in Lijiang, Yunnan, because they had refused to purchase a bracelet worth 50,000 yuan ($7,025) as instructed by their tour guide during a visit to a jade shop. This incident also went viral on Weibo (#一家人旅游未买5万手镯被赶下车#, 130 million views), sparking outrage over local travel scams and the perceived inaction of tourism authorities.

A significant factor in these discussions is how Chinese local tourism authorities have been ramping up their marketing efforts following the pandemic and China’s zero-Covid policy. Seeking to attract more domestic tourists, they’ve been exploring new strategies to promote their hometowns, particularly among younger generations. Since early 2023, various tourism bureau chiefs from across China have gone viral on platforms like Weibo, Douyin, and beyond for their innovative social media campaigns.

The marketing success of certain destinations, such as ‘BBQ town’ Zibo, has also inspired other cities or regions throughout China to go all out in presenting their best side. Some of them, such as Harbin, have succeeded in becoming yet another holiday hit.

While these kind of campaigns are generally applauded, many believe that actions speak louder than words. They argue that besides focusing on social media campaigns, local tourism authorities should do more to protect common travelers against scams, rip-offs, and fraud.

“What will you do next time this happens?” many ask, and: “what should normal people without a big social media following do when this happens to them?”

“Fu Yuanhui is a public figure, which is why this case was resolved. For regular people, nothing would happen – we don’t get heard,” another person wrote.

While many criticize Jilin authorities for aiding Fu Yuanhui without effectively addressing tourist scams, most people don’t blame Fu Yuanhui at all for seeking the help she needed. “After all,” one commenter wrote, “She does have mystical powers.”

By Manya Koetse

With contributions by Ruixin Zhang

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?