Newsletter

Weibo Watch: Shared Roots

The ‘shared roots’ stressed by Wang Yi during the China-Japan-ROK forum are not the kind of roots that matter; it’s the shared memories that connect people.

Published

1 year agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #9

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Shared roots

◼︎ 2. What’s Trending – A closer look at the top stories

◼︎ 3. What to Know – Highlighting 8 hot topics

◼︎ 4. What Lies Behind – Collective shock over Coco Lee’s death

◼︎ 5. What’s Noteworthy – Taiwanese man decapitates mother

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – Jackie Chan’s Weibo page

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – One year since Abe’s assassination

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – “Chunyuan of China’s Entertainment Industry”

Dear Reader,

“No matter how blonde you dye your hair, how sharp you shape your nose, you can never become a European or American, you can never become a Westerner. We must know where our roots lie.”

These words, spoken by Chinese top official Wang Yi during the first China-Japan-ROK forum since the outbreak of COVID-19, were intended to emphasize the power of trilateral relations and the shared Chinese, Japanese, and Korean roots. The remark attracted significant attention this week, both on Chinese social media and in English-language social media spheres, albeit for different reasons.

While many on Twitter criticized Wang’s remarks for emphasizing ethnoracial ideas of the nation, Chinese social media users actually supported his comments, stating that he had “hit the nail on the head.”

However, despite agreeing with him, they interpreted his remarks not as a call for unity among China, Japan, and South Korea to “revitalize Asia,” but rather as a critique. Some suggested that Wang’s words were a form of “high diplomacy,” where it appeared that he was praising the relations between the three countries while subtly criticizing the other two for becoming too Westernized and for deviating from their cultural roots.

The online response to Wang Yi’s remarks demonstrates that stressing these kinds of “shared roots” may not hold much significance in a time where “shared memories” are what truly matters. It is not perceived shared race that counts, but rather perceived shared history.

Two other prominent trends this week revealed that netizens were most united when collectively remembering a shared past. The first trend centered around popular culture, as millions mourned the loss of pop icon Coco Lee, who tragically passed away after an attempted suicide. Netizens shared their personal and collective memories of Coco Lee and what she meant to them, bonding through nostalgia and the vibrant pop culture era that brought them together.

The second trend centered around the memory of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, which occurred on July 7th, 1937, and led to the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). Although today’s netizens did not personally experience this incident, patriotic education campaigns in China during the 1990s and 2000s have stressed the importance of these historical events to such an extent that many feel emotionally connected to this history. This echoes official calls to never forget this incident and how it has shaped the Chinese people. The intensity of the state media campaign surrounding the 86th anniversary of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident highlights the significance of social media platforms as “patriotic education bases.”

In the end, feelings of connection, unity, and belonging are not about the shape of one’s nose or the color of one’s hair. It is about the stories that we grow up with, passed down by our families and reinforced through education, museums, and media. Particularly in the social media age, where a sense of rootedness may not be immediately apparent, it is these kinds of ‘shared roots’ that become most visible through online discourse.

This week’s newsletter includes valuable insights from What’s on Weibo news editor Miranda Barnes and Zilan Qian, who is interning with us this summer.

On a more personal note..,

I’ll be out traveling through China in the coming few weeks. For me, it will be the first occasion to get back to traveling around the country since the outbreak of Covid-19. Since I want to spend as much time as possible exploring new places and seeing the changes around me, you might temporarily see a bit less content on the site. I will share more about my travels on social media (you can follow me on Twitter or on Instagram). We will get back to our usual work flow and newsletters in August.

Having said that, I would also like to take a moment to express my gratitude to you as a subscriber. It has been eight months since we introduced the ‘soft paywall’ and two months since the inception of the Weibo Watch newsletter. As many of you may know, I have been managing What’s on Weibo single-handedly for the past decade, and these changes were necessary to ensure the sustainability of my work. While we still need more subscribers to ensure the long-term viability of our platform, I am immensely grateful to all of you who have reached out with words of encouragement and support over the past few months. Whether it’s a quick heads-up about a typo, sharing ideas, engaging in discussions, spreading the word, or even generously supporting the site through donations, please know that all of your gestures are very much appreciated.

We are dedicated to staying in tune with everyday China, keeping our finger on the pulse of the latest trends, and uncovering the stories behind the hashtags. By doing so, we aim to build a bridge between Western and Chinese online media spheres, fostering a deeper understanding of China’s ever-evolving digital media landscape. I am excited to continue on this journey and further build this community in the times ahead – and I’m happy you’re part of it.

Keep cool in the summer heat!

Best,

Manya

What’s Trending

1: July 7, 1937 | This week, Chinese social media platforms saw active commemoration of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. On significant historical occasions like this, Chinese state media accounts proactively share patriotic and nationalistic content, emphasizing the importance of remembering the history of the Second Sino-Japanese War and China’s ‘century of humiliation.’ These efforts highlight the role of Chinese social media as a prominent platform for patriotic education, reinforcing national consciousness and collective memory among the population.

2: Stressing Shared Roots | During the inaugural China-Japan-ROK forum since the outbreak of COVID-19, Chinese top official Wang Yi emphasized the deep cultural ties between the countries by highlighting their race-based similarities. While there was criticism in English-language social media circles for Wang Yi’s remarks being seen as “playing the race card,” many Chinese social media users supported his comments, stating that he “hit the nail on the head.” Despite agreeing with him, they interpreted his remarks not as a call for unity among Japan, South Korea, and China but rather as a critique of these countries for deviating from their cultural origins.

3: Cai Xukun Responds | The 24-year-old Chinese celebrity Cai Xukun recently became entangled in a scandal when allegations surfaced that he had been involved in a one-night encounter with a young woman who later revealed she was pregnant. It was claimed that Cai had encouraged her to undergo an abortion, which she ultimately did. This week, Cai finally came out and responded, asserting that there was no coercion involved in the decision and that no illegal activities took place. Nevertheless, this revelation has left many of his fans feeling disheartened and disappointed with their idol.

4: Worries over Mpox | This week, reports of several monkeypox (mpox) cases in China have gained significant attention. While the number of reported cases remains limited, and mpox is very different from Covid, netizens have expressed concerns about the possibility of another outbreak and have taken precautions by readying their disinfectant supplies.

What to Know

Showing batch to avoid a drunk driving check? This incident sparked anger on social media this week. Image via China Digital Times.

◼︎ 1. Coco Lee Death. The passing of Coco Lee (李玟, b. 1975), the Hong Kong pop diva and Chinese-American singer, has deeply saddened Chinese social media this week. Coco Lee was an iconic figure in the Asian pop music scene during the 1990s and 2000s. She made history as the first Chinese artist to perform at the Oscars and lent her voice to Disney’s Mulan, as well as singing the movie’s theme song. Her performances at the CCTV Spring Festival Gala were highly anticipated, and she also sang the theme song “Light Up the Dream” (点亮梦) for the Beijing Winter Olympics. Coco Lee battled with depression for many years and tragically took her own life at the age of 48 (Hashtag: “Coco Lee Passed Away” #李玟去世#, 4.37 billion views on Weibo).

◼︎ 2. Yellen in China. US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen visited Beijing this week for two days of meetings with Chinese Premier Li Qiang and other officials, resuming talks with China amid tensions not long after Blinken’s initial visit. While Yellen expressed concerns over China’s recently announced export control on two strategic raw materials, social media users seemed more interested in the Yunnan restaurant in Beijing where she had dinner on her first night. The restaurant, somewhat comically called ‘In and Out’ in English (Chinese name: Yi Zuo Yi Wang 一坐一忘), is a local favorite in Sanlitun. Among other things, Yellen was served spicy potatoes with mint and stir-fried mushrooms, leading to jokes about how the food would affect her and about American budgets being so low that they had to pick such an economical local restaurant. Yellen repeatedly bowing when meeting with China’s He Lifeng also triggered some discussions about American weakness. (Hashtags: “U.S. treasury Secretary First Meal in Beijing” #美财政部长抵京第一餐#; “Yellen Arrives in Beijing” #耶伦抵达北京#)

◼︎ 3. Avoiding DUI with Police Batch. A video went viral on Chinese social media this week showing a driver being let off the hook for a drunk driving check in Pingdingshan, Henan, after a passenger in the back seat presented his police officer’s identification card, demanding special treatment. The man was later identified as Xu, the former head of the Communication Department of the Jia County Public Security Bureau. Xu has reportedly since been dismissed from his position. The traffic police who led him off the hook received “disciplinary punishment.” The incident ignited public outcry, highlighting concerns about privilege and corruption. (Hashtag: “Strict Investigation Into the Privilege Corruption Behind Incident of Policeman Showing Batch to Avoid DUI Police Stop #严查民警亮证逃查酒驾事件中的特权腐败#)

◼︎ 4. Alibaba’s Ant Group Gets 7.1 Billion Yuan Fine. On Friday, Chinese authorities announced a fine of 7.12 billion yuan ($984 million) for Chinese fintech giant Ant Group and its subsidiaries, concluding a 2 year probe into the company. The fine is a result of past violations in areas such as corporate governance, financial consumer protection, and involvement in banking and insurance activities. The penalty marks one of the largest fines ever imposed on an internet company in China. (Hashtag: “Ant Group and Subsidiaries Fined 7.123 Billion Yuan” #蚂蚁集团及旗下机构被罚款71.23亿元#)

◼︎ 5. Cheating Official’s ‘Holding Hand Gate’. You might remember the Chinese official and PetroChina subsidiary executive Hu Jiyong (胡继勇) who was caught walking hand in hand with his mistress and co-worker Ms. Dong during a recent business trip in Chengdu (read here in our previous newsletter). This week, the results of the investigation into the incident were announced by the company’s disciplinary committee. It was found that Hu Jiyong violated Rules of Personal Conduct as well as the Code of Conduct on Integrity by having an extramarital affair with a co-worker and using official travel arrangements for personal purposes. Hu Jiyong has been expelled from the Party, dismissed from public office, and Ms. Dong’s employment contract has also been terminated. (Hashtag “Official Announcement on Results of ‘Holding Hands Gate'” #官方公布牵手门处理结果)

◼︎ 6. Zhihu No Longer Allows Anonymous Function. China’s largest Q&A discussion site, Zhihu, made an announcement this week regarding the removal of the anonymous function from its latest app version. The decision aims to promote “constructive discussions” by disallowing users from posting anonymously, whether it be asking or answering questions. However, for existing content, users still have the option to use their nicknames instead of their real names. Real name authentication (实名制) was already implemented by Zhihu as part of Chinese internet governance back in 2017, but users were still able to post under pseudonyms. While some people support this change, appreciating the transparency it brings and its potential to prevent online bullying, others feel that anonymity is an integral part of the platform’s essence. (Hashtag “Zhihu Announces It Will Take Anonymous Function Offline” #知乎宣布将下线匿名功能#).

◼︎ 7. HK Police Offer Rewards for Arrests of Exiled Dissidents. This week, Hong Kong authorities made an announcement stating that they have offered cash rewards for eight overseas pro-independence activists who have been accused of violating the national security law in the Chinese territory. A bounty of HK$1 million ($127,650) has been offered for information that could lead to the arrests of these individuals. Among the targeted activists are three former lawmakers living in exile and five individuals who have been accused of promoting separatism. (Hashtag: “Hong Kong Police Issue Reward of HKD 1 million Arrest of Ted Hui Chi-Fung and Seven Others” #香港警方悬红100万港元通缉许智峰等8人#).

◼︎ 8. Red Alert Heat Wave. On July 6, Beijing issued a red alert for extremely high temperatures as temperatures in most areas of the city were expected to rise above 40 degrees (104 degrees Fahrenheit). It was the second “red level” warning for heat issued this summer. The city government advised outdoor work to be suspended when temperatures run high, and ordered authorities to take emergency measures to prevent heatstroke. Northern China has seen exceptionally high temperatures this summer. Hebei also issued a red warning for most areas in the province, as some parts saw temperatures between 41 and 43 degrees (105.8 and 109.4 degrees Fahrenheit). (Hashtag: Highest Temperature In Some Hebei Area to Reach 43℃. #河北局地最高气温可达43℃#)

What’s Behind the Headlines

Image of Coco Lee by Neonqeelin / Wikicommons.

The Collective Shock over Coco Lee’s Death

The sudden tragedy of pop star Coco Lee’s death in the past week has left fans shocked and deeply saddened. The Hong Kong-born singer’s passing occurred after she was discovered in an attempt to take her own life. Many fans found it difficult to believe, as Coco Lee had always exuded energetic inspiration. This news particularly resonated with Chinese millennials, who felt a strong emotional impact. A blogger named LaoChai (老柴) attempted to capture this sentiment and express what Coco represented to them:

“The younger generation may struggle to comprehend how special it was for us millennials to experience the turn of the millennium. Regardless of the circumstances within our own small families, everything seemed to be heading towards a bright, open, and prosperous future. People were filled with hope, and it felt as though the joyous ride would never cease. Information was limited, and we relied on DVDs for films and cassette tapes for music. It was a golden era for Chinese music, featuring the best singers from Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. We were soft, young, and impressionable, eager to explore the world. The melodies and film clips from that era effortlessly evoke our collective memories.”.

Many individuals resonated with this interpretation, especially considering the challenges faced during the COVID-19 era and China’s current economic environment.

Coco’s tragic death also sparked a broad discussion about mental health, as she had previously revealed her own battle with depression. State media and experts joined forces to raise awareness about mental health — an issue that the country had long overlooked and stigmatized.

However, some people suddenly found their Weibo pages flooded with promoted ads appearing as “quizzes to determine if you have depression.” One person remarked, “While it is good to raise awareness, it is important to seek proper help and diagnosis instead of relying on random online quizzes. It seems like everyone is suddenly depressed when sometimes you just have a bad day like the rest of us!”

What’s Noteworthy

Image on right side via Up Media.

84-Year-Old Mother Decapitated in Taiwan | A 59-year-old man by the name of Lian from Taiwan was arrested on suspicion of murder in New Taipei’s Xindian District on Tuesday. Local police discovered a horrific scene inside the man’s elderly mother’s apartment. They were alerted by a friend of the victim who discovered Lian covered in blood next to his mother’s lifeless body.

According to media reports, the man is believed to have attacked his mother from behind with a knife while she was eating. After realizing that she was still alive, he grabbed another knife and continued his assault until his mother’s neck was completely severed. The two kitchen knives were found at the scene along with the severed body and head.

The police are currently investigating the case and looking into the motives behind the crime. It is reported that the mother and son had a “good relationship” and often spent time together. The incident has gained significant attention on social media, with a related hashtag (#台湾一男子持刀砍下84岁母亲头颅#) receiving over 160 million clicks.

What’s Popular

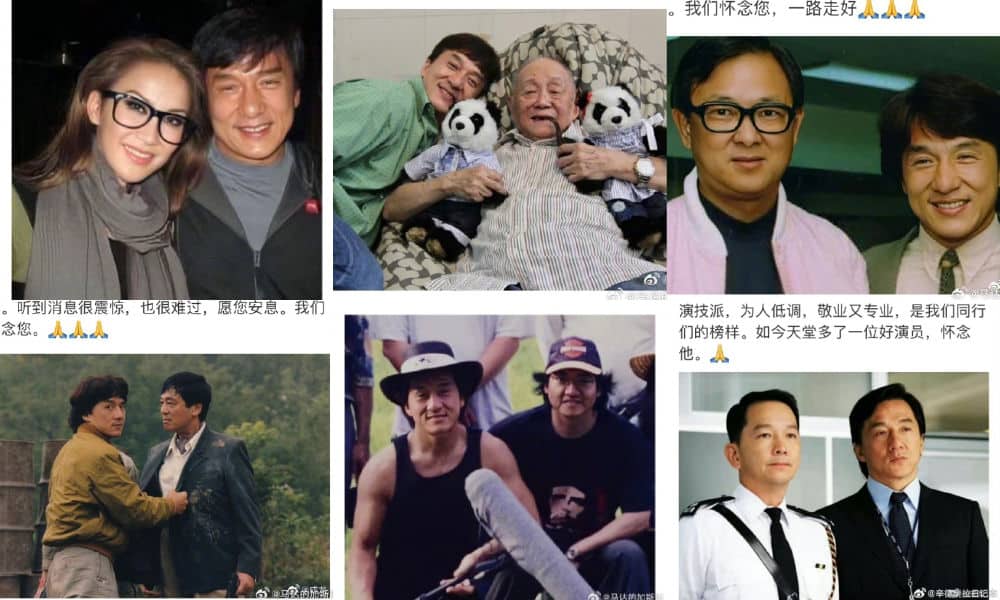

Jackie Chan’s ‘Memoriam’ Weibo Page | “Somebody once said that aging doesn’t happen all at once; it consists of many small farewells.” While the recent passing of Coco Lee has been a prominent topic on Chinese social media, the loss of such an influential figure has evoked sadness and nostalgia among many.

Amidst these discussions, a Weibo blogger (@马达的加斯加) pointed out an observation about the Weibo activity of Jackie Chan, the renowned Hong Kong actor and martial artist (b. 1954). The blogger noted that Jackie Chan’s recent posts on Weibo have primarily been farewells to friends who have passed away over the past year. He paid tribute to Coco Lee, honored Chinese artist Huang Yongyu, Hong Kong film director Alex Law, actor Kenneth Tsang, and bid farewell to Taiwanese martial artist Jimmy Wang Yu.

“One by one, old friends fade away like leaves in the wind. On Jackie Chan’s Weibo page, I witnessed an autumn scene,” wrote the blogger. The post quickly gained traction, resonating with many users who shared similar sentiments and expressed their mourning for Coco Lee and other iconic figures lost in recent years.

What’s Memorable

Abe’s portrait via Wikicommons.

Chinese Responses to Abe’s Death | It has been a whole year since the assassination of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in Nara on July 8, 2022. In this week’s pick from the archive, we reflect on an incident that unfolded in the aftermath of this event. A Chinese reporter based in Japan appeared on air to discuss the attack on Abe but faced severe backlash when she visibly struggled to hold back tears. Her emotional display led to accusations of being unpatriotic, and she even received threats for “crying over a Japanese right-winger who has no respect for the history of the invasion of China.”

Disturbingly, the situation took a further distressing turn when the reporter later attempted to take her own life. Presently, she continues to work in Japan, but even after the passage of one year, she continues to be subjected to cyber-bullying and harassment, due to that tearful moment captured during the live broadcast.

Weibo Word of the Week, by Zilan

Background image source via Sohu.com.

Staying Pure in Times of Scandal | Our Weibo Word of the Week is 内娱纯元 (nèiyú chúnyuán), “Chunyuan of the Mainland entertainment industry.”

“Chunyuan of the Mainland entertainment industry” refers to idols in Mainland China who are regarded as flawless and worthy of admiration. The term “内娱” (nèiyú) is a shortened form of “内地娱乐圈” (nèidì yúlèquān), which means the Mainland entertainment industry. It encompasses the diverse group of celebrities actively involved in China’s showbiz (sometimes also including Hong Kong or Taiwan artists who are popular in the Mainland). Meanwhile, “纯元” (chúnyuán), meaning ‘pure essence,’ symbolizes individuals seen as unblemished by reality.

In the popular TV drama “Empresses in the Palace” (甄嬛传), Chunyuan refers to the deceased first wife of the emperor, who is frequently mentioned as a paragon of perfection, surpassing all other women in the palace, although she never appears on screen.

In light of the numerous scandals involving idols in mainland China in recent years, including prominent stars like Fan Bingbing (范冰冰), Kris Wu (吴亦凡), and more recently, Cai Xukun (蔡徐坤), discussions have emerged around identifying figures who remain untainted by controversy and are deserving of being cherished as flawless role models.

Some netizens have suggested former EXO members Lu Han (鹿晗) and Zhang Yixing (张艺兴), who were part of the same group as Kris Wu but have managed to maintain a clean reputation. Others nostalgically mention influential celebrities who have passed away and are fondly remembered, like Leslie Cheung (张国荣) or Anita Mui (梅艳芳).

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

Also Read

Newsletter

The Hashtagification of Chinese Propaganda

From tech-powered messaging to pop culture politics, China’s propaganda has undergone a major transformation in the social media age.

Published

2 weeks agoon

October 13, 2024

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #38

Dear Reader,

October 1st marked the 75th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Flags, hearts, balloons—National Day celebrations turned Chinese social media red.

Among the key players in leading the propaganda around National Day was People’s Daily, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of China. To commemorate the occasion, People’s Daily published a column titled “Today’s China, Tomorrow’s China” (今天的中国,明天的中国)1, outlining a clear vision for the future and emphasizing China’s rise under the Party’s leadership.

The article highlighted how hard work and perseverance are crucial to achieving the ‘China Dream,’ with national unity being the driving force behind the country’s continued progress. It also stressed the pivotal role of China’s youth in shaping the future of the nation.

The article was accompanied by four posters, each conveying a specific message:

“Today’s China is a China where dreams are continuously realized” (今天的中国是梦想接连实现的中国)

“Today’s China is a China full of vibrancy and vitality” (今天的中国是充满生机活力的中国)

“Today’s China is a China that carries on the national spirit” (今天的中国是赓续民族精神的中国)

“Today’s China is a China closely connected to the world” (今天的中国是紧密联系世界的中国)

A related hashtag, “75th Anniversary of the Founding of the People’s Republic of China” (#新中国成立75周年#), received over 590 million views on Weibo.

But People’s Daily also put out a much simpler message, posting the hashtag: “I Love You, China” (#我爱你中国#).

This hashtag was accompanied by an online poster featuring the Chinese characters for “China.” The characters in the picture are shaped by various symbols representing both traditional and modern China, from lanterns and Tiananmen to rockets and railways. That post was shared over six million times.

The immense popularity of the poster and the “I Love You China” hashtag page, initiated by People’s Daily and garnering over eight billion views through the times, highlights the strength of Party-led propaganda in the social media era.

A Major Shift

A few days ago, De Balie, a cultural venue in Amsterdam, hosted an event focused on how Chinese state propaganda has evolved, coinciding with the 75th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. As a participant in the discussion, I’ve recently been reflecting on the nature of Chinese propaganda in the digital age.

Propaganda has always been a key element of the Party’s strategy—not just for the past 75 years, but for over a century. Since the founding of the Central Propaganda Department in 1924, three years after the establishment of the Communist Party, propaganda has played a central role in shaping official narratives. China’s propaganda system exerts significant influence over nearly every major medium involved in disseminating information within the country, from news outlets and educational institutions to cultural organizations, artistic circles, and literary institutions.2

China’s rapid digitalization and the rise of social media posed significant challenges for officials in disseminating propaganda, particularly in the early 2010s when there was an explosion of self-media, app culture, and intense celebrity idolization. Amid this cacophony of new media channels, Party propaganda was increasingly overlooked as people’s attention shifted to what they found more engaging, such as movie stars and other celebrities representing new, exciting lifestyles.3

This was not the first ‘disruptive force’ the Party Propaganda Department had to confront. (Side note: Chinese officials, aware of the negative connotations of ‘propaganda’ in English—though it’s a neutral term in Chinese, 宣传—later changed its English name to the ‘Publicity Department.’)

As Stefan Landsberger notes in Chinese Propaganda Posters,4 the Party’s well-established system for propaganda and political education faced similar challenges in the 1980s following the Open Door policy. This policy significantly transformed Chinese society, bringing a wave of foreign cultural and lifestyle influences and accelerating the spread of electronic media.

Although the spread of non-official media and information may have disrupted the central messaging dynamics of the Propaganda Department in the 1980s, the growing presence of radio and television sets in people’s homes also allowed Party leaders to shift their focus from propaganda posters to new media as a means of communicating political messages.5

A similar shift has occurred over the past seven to eight years when it comes to social media. Initially, propaganda authorities struggled to convey official messages on Weibo and other emerging digital platforms, but in 2017, China’s propaganda system saw a pivotal change in its approach to domestic social media, particularly on Weibo.

Instead of trying to pull young people into traditional Party narratives, it began weaving propaganda directly the fabric of social media itself —blending politics seamlessly into the digital content young audiences were already engaging with.

No three-and-a-half-hour speech, but a three-and-a-half minute video. In 2017, Chinese state media explained China’s new strategies through catchy rap music and trendy graphics. Read more.

2017 was a pivotal year for Chinese propaganda with three major events: the One Belt One Road (OBOR) Summit, the 19th Party Congress, and the APEC Summit. For each occasion, publicity authorities launched distinctive, high-profile campaigns.

The OBOR Summit featured several high-production videos with catchy tunes, often starring foreigners (though some found them awkward). The 19th Party Congress saw a flood of new propaganda videos and initiatives, including a clapping game produced by Tencent that allowed users to applaud Xi Jinping’s speech. Meanwhile, the APEC Summit videos saw a manga-style version of Xi Jinping, portraying him as lovable and approachable.

Hashtagification of Propaganda

Propaganda departments in China have adapted various strategies over the past few years to make official Party narratives more appealing by adjusting to the fast-paced, fleeting, and trendy nature of China’s social media environment. I’d call this the ‘hashtagification’ of Chinese propaganda—turning political messaging into viral trends by embedding it in hashtags and social media content. These are essentially hashtag-driven narratives that netizens can easily engage with and share.

Within this movement, I see six major strategies of digital propaganda emerging on Weibo and other social apps, such as Douyin, from 2017 to 2024.

📌 1. Old Message, New Media: Revival of Classic Propaganda

The types of posts that People’s Daily shares around National Day and other celebrations often echo classic nationalist messages about unity and national pride. This is part of a broader strategy within China’s social media propaganda, focusing on strong, simple messages that, at their core, are not much different from the political narratives promoted in previous decades. However, these messages are now disseminated through modern channels, using more sophisticated techniques and production methods. These can include online posters, as well as music or high-quality videos (example).

📌 2. Double Agenda: Foreign-Facing Propaganda with Domestic Goal

Although there’s traditionally been a clear distinction between domestic propaganda and waixuan (“external propaganda”), the past few years have seen the rise of a new kind of propaganda. It appears to target an international audience but is actually aimed at bolstering domestic support and reinforcing a positive image of China. Assertive or aggressive videos and posts, supposedly directed at foreign viewers, are often used to stir national pride at home. A good example of this is the Xinhua video series featuring Young Lady Guoshe (国社小姐姐), whose real name is Wang Dier (王迪迩), an anchor for Xinhua who previously worked for CCTV. If you’re unsure what this looks like, check the full clip here.

📌 3. Grassroots ‘Propaganda’ in Official Communication

Over the past few years, particularly during the Covid period, official channels began repurposing satirical online artworks created by independent artists or popular nationalistic influencers as a form of national propaganda. Much of this art was produced by Chinese cartoonists and artists, mocking Western hypocrisy and political leaders. These pieces were then retweeted and widely shared by official Chinese channels, amplifying domestic support and fueling anti-Western sentiment. You can read more about this trend here.

‘Investigate Thoroughly! Except Here’ (‘彻查!除了这儿’) satirical illustration by artist 半桶老阿汤 / Half Can of Old Soup in response to US calls for investigation into the origins of Covid in China while ignoring a possible link with Fort Detrick. This post was shared by the Communist Youth League on social media.

📌 4. Tech-Driven Party Messages

The use of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and gamification by Chinese state media serves a dual purpose: reinforcing the Party’s messaging while simultaneously showcasing China’s digital innovation. By integrating technology with propaganda, the Party’s message becomes more engaging and interactive, while also projecting China as a leading tech power. For instance, in recent years, the annual CCTV New Year’s Gala has become a platform to display China’s cutting-edge digital technologies on stage. Online, tech and propaganda are frequently intertwined, such as in the aforementioned clapping game by Tencent. Other examples include virtual newsreaders for state media and the ‘Study Xi app’ (Xuexi Qiangguo), which allows users to earn points for engaging with official Party content. You can read more about these innovations here and here.

📌 5. Pop Culture Propaganda

By ‘Pop Culture Propaganda,’ I refer to the blending of propaganda with pop culture in various ways. One example is the use of Chinese celebrities to promote official Party messages, such as the 2017 campaign for China’s New Era (hashtag: ‘Give A Shout-Out to the New Era‘) or the Social Credit song launched by the Communist Youth League. Another form of this propaganda involves colorful and cute animations and cartoons that primarily appeal to younger generations. These often incorporate Japanese influences, like anime and manga, which are especially popular among Chinese youth, making propaganda more accessible and attractive. Currently, many manga-themed propaganda-style images are circulating, blurring the lines between fan-made content and official productions (as mentioned in point 3!).

Official or not? Official channels sometimes share non-official digital art on their pages, while everyday netizens often post official “pop propaganda” on their own accounts (Images via Weibo).

📌 6. Guerrilla Propaganda: Coordinated, Multi-Front Engagement Across Media & Influencers

A final technique I’ve observed on Chinese social media since 2016-2017 is topic-centered propaganda that is spread simultaneously across multiple platforms. In these campaigns, social media, local authorities, businesses, and influencers collaborate to create a coordinated wave of messaging. A notable example is the 2021 Xinjiang cotton campaign, which followed H&M and the Better Cotton Initiative’s boycott of Xinjiang cotton over alleged human rights abuses. In response, a massive pro-Xinjiang cotton campaign erupted on Weibo, with state media, Baidu, e-commerce platforms, and celebrities uniting to cancel H&M and support Xinjiang-sourced cotton. The campaign was highly effective, with the hashtag “Wo Zhichi Xinjiang Mianhua” (“I Support Xinjiang Cotton” #我支持新疆棉花#) receiving over 8 billion views on Weibo—comparable to the “I Love China” hashtag.

Propaganda posters by People’s Daily at the time of the Xinjiang cotton controversy. The posters say “Xinjiang Mianhua” (Xinjiang cotton) in a similar font to the H&M logo, the “H” and “M” within ‘mianhua‘ being identical to the H&M letters.

What’s particularly interesting about propaganda in China’s social media era is that, unlike previous periods, it’s no longer a one-way street from billboard to pedestrian or from TV screen to viewer. Social media is inherently interactive, and despite the overwhelming presence of official accounts on platforms like Weibo, WeChat, and Douyin, there are still over a billion individual social media users in China who can choose to scroll away, mute, or ignore these messages.

While the line between state media and other accounts is increasingly blurred, state propaganda continues to compete for attention in a dynamic and vibrant online culture.

Stefan Landsberger – In Memoriam

There is so much more to say about all of this, and it only highlights how multi-faceted and complex the topic of propaganda in China truly is.

No one understood this better than sinologist Prof. Dr. Stefan Landsberger. I was shocked and deeply saddened to hear of his sudden passing this week. Coincidentally, I received the news while working on this newsletter, with his beautiful Chinese Propaganda Posters book open on my lap.

If you’re not familiar with his name, you might have come across his work if you’ve ever read anything about Chinese propaganda. Landsberger was a leading authority on the subject, having spent decades—since the late 1970s—collecting an extensive array of posters and conducting thorough research in the field. His collection grew to become one of the largest private collections of Chinese propaganda posters in the world.

Landsberger was an Associate Professor of Contemporary Chinese History and Society at Leiden University. In that role, he also taught me Chinese Modern History when I was an undergraduate there. He was a dedicated teacher—often critical, which made him intimidating to some students—but deeply appreciated by most for his brutal honesty and his immense passion for Chinese history and modern Sinology.

One memory from 2018 stands out. I was in China as a post-graduate student and took a taxi on a cold and rainy January night in Beijing. During the ride, I struck up a conversation with the driver, who asked me where I was from. When I told him I was Dutch, he proudly shared that he had a Dutch friend—one of his dearest, he said, whom he’d known since the early 1980s. That intrigued me, as I’d never heard anything like that from a Beijing taxi driver before. As we continued talking, he mentioned that his friend was a teacher and then showed me a photo on his phone of them together. I was surprised to see that the man in the picture, smiling warmly beside the taxi driver, was none other than my own teacher Stefan Landsberger.

In a city of 21 million people, I had somehow hailed a cab driven by one of Landsberger’s oldest friends in the city, whom he had known since he was a student in Beijing. I shared this story with Dr. Landsberger later through WeChat—it made him laugh. This chance encounter left a lasting impression on me, not just because of the coincidence, but because it spoke volumes about Landsberger’s enduring love for China and his ability to cultivate deep, lasting friendships. It showed his loyalty, not just to his work and research but to the people and connections he built over decades.

Landsberger will be greatly missed. His contributions to the growing body of work on Chinese propaganda are invaluable. This ever-evolving phenomenon can only be fully understood by examining both its current trends and its historical roots—and Landsberger’s work will forever be foundational in that effort, helping to better understand “Today’s China, Tomorrow’s China.”

My thoughts are with his family and friends during this difficult time.

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

1 Ren Ping, “今天的中国,明天的中国” [Today’s China, Tomorrow’s China], People’s Daily, September 29, 2024, https://weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309405083853533610297

2 David Shambaugh, “China’s Propaganda System: Institutions, Processes and Efficacy,” The China Journal 57 (2007):27-28.

3 See Willy Lam quoted in Yi-Ling Liu, “Chinese Propaganda Faces Stiff Competition from Celebrities,” AP News, October 23, 2017, https://apnews.com/article/1616c60ab01d43caae024d34cb98d532 (accessed October 12, 2024).

4 Stefan Landsberger, Chinese Propaganda Posters: From Revolution to Modernization (Amsterdam: The Pepin Press, 2001): 11.

5 Landsberger, Chinese Propaganda Posters, 15.

PS: If you’re a loyal reader of Weibo Watch, you might have noticed I’ve been trying out some changes in the newsletters lately to deliver more frequent updates while balancing things on the site. Don’t worry if this edition is missing the hot topics section—it’s not going anywhere! But if there’s anything you’d love to see in the newsletters moving forward, please let me know. Your feedback really helps with planning future editions.

What’s New

Golden Week | China celebrated its National Day Holiday earlier this month. This week-long holiday, also known as the Golden Week, is a popular time for trips, travel, and sightseeing. On Chinese social media, it has become somewhat of a tradition to post about just how busy it is in China’s various sightseeing spots. This is often done by using hashtags including “人人人人[place]人人人人.”

Being Watched | Could it be that someone is watching you while you think you’re all alone in your private hotel room? Without realizing it, some guesthouses or hotels may have hidden cameras secretly recording their guests. This issue has long been a source of concern in China and has recently become a hot topic again. The Chinese Douyin and Weibo blogger @ShadowsDontLie (@影子不会说谎), an ‘anti-fraud’ influencer, has made it his mission to expose hidden cameras in guesthouses. The controversy following his recent discoveries are perhaps just a tip of the iceberg – we’ll follow up on this story soon. Meanwhile, check out the full story here.

For the Clicks |The debate over influencers performing dangerous stunts for clout is ongoing in the West, but it has also recently gained attention in China after another motorcycle influencer was killed in a crash.

China’s Image | On October 10, 2024, De Balie hosted an event discussing how China portrays itself to its citizens and the world, marking the 75th anniversary of the People’s Republic. The panel explored the evolution of Chinese state propaganda, the public’s response, and how the emergence of digital China has reshaped the landscape. Speakers included Ardi Bouwers, Florian Schneider, Qian Huang, and myself (Qian and I appear in the second half). You can watch the full event here.

What’s Memorable

Old one-child policy propaganda slogans, especially in rural areas, remain visible on walls across China, even though they contradict the government’s current push for families to have more children due to declining birth rates. While efforts to remove these outdated slogans have intensified, some people question the urgency.

Weibo Word of the Week

Rushing to the Counties

Our Weibo word of the week is 奔县 (bèn xiàn), which translates to “rushing to the county.” This term has recently surged in Chinese media after this month’s National Day holiday, a popular travel time, saw an increased popularity of lesser-known county-level towns instead of large cities or famous tourist destinations.

According to the latest travel industry reports following the week-long holiday, bookings have significantly increased compared to last year, despite last year already being notably crowded. This year, 765 million trips were taken nationwide, marking a 10.2% increase compared to pre-pandemic 2019.

Last year, ‘domestic travel’ was the key trend, with the so-called “special forces travel” (特种兵旅游 tè zhǒng bīng lǚxíng) becoming popular among Chinese youth. That trend was all about visiting as many places as possible at the lowest cost within a limited time, often involving incredibly tight schedules and 12-hour travel days.

This year, the focus has shifted to a more relaxed and cost-effective approach. This has turned county-level tourism (奔县游 bènxiànyóu) into a new trend. People are not just visiting county-level towns to see family; more young travelers from China’s major cities are exploring nearby smaller towns for “micro-holidays” (微度假 wēi dùjià).

County-level towns in China are smaller than bigger cities like Beijing or Shanghai, but still big enough to usually have plenty to do as they are important hubs for the surrounding rural areas. In these county-level destinations, the cost of hotels and meals tends to be much cheaper than in popular tourist hotspots. Staying closer to home also reduces travel time and expenses, while offering the opportunity to visit lesser-known locations and avoid the peak tourist crowds.

According to The Observer, places like Jiuzhaigou, Anji, Shangri-La, Pingtan, Dujiangyan, and Jinghong saw booking increases of 109%, 86%, 74%, 67%, 51%, and 50%, respectively.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

China and Covid19

Weibo Watch: Small Earthquakes in Wuhan

How Wuhan is shaking off its past with a new wave of innovation, the hot topics to know, and the Weibo catchphrase of the week: ‘the Three Questions of Patriotism.’

Published

4 weeks agoon

September 27, 2024

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #37

Dear Reader,

“Wuhan Earthquake” (#武汉地震#) momentarily became the number one trending topic on Weibo this Friday night, after residents of Jiangxia District reported feeling their homes and buildings shake. “Was there an earthquake, or am I drunk?” some wondered.

I also felt a bit tipsy in Wuhan this month. Neon signs, dancing livestreamers, flying drones, bustling night markets, and holographic lights. On my first night in Wuhan, the lights made me dizzy and I discovered that the city was nothing like I had imagined.

Until now, I couldn’t help but associate Wuhan with the wet market, crowded fever clinics, and China’s first Covid hospitals. As the world watched the pandemic unfold in 2020, Wuhan became instantly famous as an early epicenter of the Covid-19 crisis. It became known as the quarantined city, the city of Dr. Li Wenliang, and the city of the “invincible Wuhan man.” At the time, it seemed like such a monumental event that Wuhan would not recover anytime soon, even after enduring the worst peak of Covid.

Now, over four years later, everything feels different. I felt a rush of energy as I strolled through the lively streets. It was evident that Wuhan is much more than the city that gained global notoriety as the pandemic hotspot. Beyond its vibrant atmosphere, it is making international headlines for its leadership in autonomous driving, having emerged as the world’s largest testing ground for self-driving cars, particularly in unmanned ride-hailing services.

Baidu’s Apollo Go, referred to as Luobo Kuaipao (萝卜快跑) in Chinese, is the driving force behind the robotaxi revolution in Wuhan. Since their arrival earlier this year, they have become a hot topic on Chinese social media, and I was eager to experience it for myself.

(Brief explainer: Luóbo (萝卜) means radish or turnip in Chinese, but when pronounced, it sounds similar to “robo.” Kuàipǎo (快跑) translates to “run fast.” Combined, it creates a playful name that can be interpreted as “Radish Runs Fast” or “Robo Go.” I’ll use ‘Luobo’ here, as it is the most common way to refer to Apollo Go in China and has a cute sound.)

In the areas where the robotaxis operate, people already seem to have become accustomed to the driverless ‘Luobo.’ During a 1.5-hour ride in the unmanned taxi—I took a long journey and then needed to return again—I was surprised to see so many of them on the road. Other drivers, motorcyclists, and passengers didn’t even bat an eye anymore when encountering the new AI taxi.

Currently, there is an active fleet of 400 cars in Wuhan, and Baidu plans to expand this to 1,000 in the fourth quarter of this year. Although these taxis still comprise only a fraction of the city’s entire taxi industry, their impact is noticeable on the roads, where you will inevitably encounter them. I stood at one drop-off point near an urban shopping center for at least forty minutes and witnessed passengers being dropped off continually, with some proceeding their journeys into areas where Luobo doesn’t operate by calling the ride-hailing service Didi from there.

As for the experience itself, it was thrilling to see the steering wheel move with no driver in the front seat. I was surprised at how quickly I adapted to something so unfamiliar. It’s incredibly comfortable to have a car to yourself—no driver, no worries—while you choose your own music (and sing along), set the air conditioning, and relax as the Luobo navigates the traffic.

Even inside the vehicle, Baidu emphasizes the safety of their self-driving cars, providing information about how Apollo Go has accumulated over 100 million kilometers of autonomous driving testing without any major accidents, thanks to a strict safety management system.

If you close your eyes, the experience feels like riding with a regular driver. Luobo speeds up, slows down, and occasionally makes unexpected maneuvers when a car or bike suddenly approaches. It ensures there’s enough space between itself and the car in front. While I can’t say that merging onto the highway or encountering unexpected traffic situations didn’t feel a bit scary, I soon felt at ease and came to rely on the technology.

That said, there are still bumps in the road. Luobo has often been ridiculed on Chinese social media for getting stuck at a green light, stopping for a garbage bag, or struggling to make a U-turn. While riding and observing the robotaxis in Wuhan, I noticed plenty of honking and road rage as Luobo chooses safety first, often appearing sluggish, earning them the nickname ‘Sháo Luóbo’ (勺萝卜/苕萝卜, “silly radish”).

While Luobo might still have its silly moments, it is a serious part of the future. Already, it is popular among commuters for its low cost, privacy, and convenience.

After spending an entire morning riding and watching the Luobos, I excitedly felt like I had experienced a glimpse of the future. Right now, Luobo Kuaipao operates in various cities across China, including Beijing, but it’s still in the testing phase there—none of my friends from Beijing have ever seen or taken one yet. However, this will likely change soon, heavily relying on policy support.

That night, I spoke to a young local in a busy commercial area near my hotel. Like many residents, he was curious about where I came from and what I was doing in Wuhan. (During the four days I spent there, I noticed very few foreign tourists.) We briefly discussed the pandemic; he reflected on the difficulties it brought but treated it as something from the past—just another bump in the road in the city’s long history.

Instead of dwelling on the pandemic, our conversation focused on the future: Wuhan’s robotaxis, his confidence in China’s technology, and the rising importance of his country on the geopolitical stage. He was just one of several young people I spoke to, from shopkeepers to students, who seemed very focused on China’s growth and development and how its technological advancements reflect its position in a world where the U.S. is no longer leading.

When it comes to China’s driverless innovations, they are shaking the foundations of transportation like an earthquake. Besides Apollo Go, companies like Pony.ai (小马智行), WeRide (文远知行), SAIC Motor (上汽集团), AutoX (安途), FAW (一汽), Changan Automobile (长安汽车), BYD (比亚迪), Yutong (宇通), and many other industry players are also working to realize driverless passenger cars, shuttle services, freight trucks, delivery vehicles, public transport buses, and much more.

What we’re witnessing in Wuhan is merely a glimpse into a future under construction, actively promoted by Chinese state media. Over the past week alone, CCTV featured Luobo Kuaipao in three segments as a key example of China’s new technological advancements and the national strategy to build a strong tech-driven economy.

As I left Wuhan in a traditional taxi, I suddenly felt like a time traveler. Wuhan was the birthplace of the 1911 revolution and will also appear in foreign history books as the initial epicenter of the Covid-19 pandemic. Now, it is at the center of an international robotaxi revolution, and it won’t be the same the next time I return.

While my friendly elderly driver—I estimated him to be in his late 50s—honked at other cars, I realized he had witnessed many other revolutions, including the Cultural Revolution as a young boy, the economic reforms, and the major social changes of the 1980s, as well as the digital revolution of the 2000s. With the growth of Wuhan’s robotaxi fleet, his job might be affected, adding another tremor to his city and his life—though he may already be retired by then.

As he helped me with my luggage and wished me a safe trip home at the Wuhan Hankou Station, I couldn’t help but feel nostalgic about how everything always changes and gets shaken up as we move forward into a future driven by technology.

As for Friday’s earthquake in Wuhan—it turns out it was a 1.6. Despite the online interest in the topic, it means virtually nothing in a city where things of much greater magnitude are happening.

If you’d like to know more about my experiences and the slight setback I encountered while searching for Wuhan’s robotaxis, check out the short videos I made here:

Part 1 (also on Instagram)

Part 2 (also on Instagram).

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

What To Know

🚀 China’s First Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Test-Launch Since 1980

On the morning of September 25, China announced a successful test launch of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) carrying a ‘dummy warhead’ into the Pacific Ocean. This marked the first ICBM launch in decades, described by official media as part of routine annual training.

The People’s Daily Weibo account of the Communist Party shared a video of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) announcing the successful test launch, accompanied by suspenseful and patriotic music, specifically the “March of the Steel Torrent” (钢铁洪流进行曲) (see video). This launch quickly became a trending topic (#我军向太平洋发射洲际弹道导弹#). While Chinese state media claimed that Beijing informed relevant countries in advance, Japan stated that it did not receive any prior notice, further heightening tensions between China and Japan.

🇯🇵 Aftermath of Japanese Schoolboy Stabbing

The incident in which a Chinese man fatally stabbed a ten-year-old Japanese schoolboy near the Shenzhen Japanese School on September 18 has become a widely discussed topic this month. The attacker, a 44-year-old Chinese national, was immediately arrested. However, discussions about the stabbing are ongoing, as it has sparked a wave of anger in Japan, where critics argue that anti-Japanese sentiments in China are fueled by official media and national education.

Meanwhile, China and Japan have effectively resolved their diplomatic dispute regarding the Fukushima water discharge, with some suggesting a connection between the two events. China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning (毛宁) stated on September 20 that the issues are not related (#中日共识与日本男童遇袭无关#). Beyond the geopolitical implications, the international media coverage of the stabbing incident has also provoked anger on Chinese social media, where many netizens reject the supposed negative portrayal of China. The topic is quite sensitive and continues to face significant censorship online.

📱 Huawei Trifold Phone

The launch of Huawei’s ‘trifold’ phone earlier this month generated significant excitement in China, with many believing that Huawei—and, by extension, China—is now at the forefront of innovation in the folding screen smartphone race. The Mate XT is the first triple-folding screen phone, leading some top commenters to proclaim, “Huawei’s innovation capability is truly the best in the world. While other manufacturers are still researching foldable phones, Huawei has already released the trifold.”

During my travels in China over the past few weeks, I visited several Huawei stores, but unfortunately, the trifold was never on display; it’s available only by reservation and has allegedly garnered millions of pre-orders, despite its hefty price tag of CNY 19,999 (USD 2,850). There’s also been some lighthearted banter surrounding the phone, including a viral post that humorously depicts what it looks like when you make a phone call with the screen unfolded (it looks ridiculous), and a user who taped two phones together to create a sixfold.

👴 Retirement Age Discussions

News came out last week that China will raise its retirement age for the first time since the 1950s. China’s current retirement ages are among the world’s lowest. Facing an aging society and declining birth rates, the ages will now be increased in a step-by-step implementation process: 50 to 55 for women in blue-collar jobs, 55 to 58 for females in white-collar jobs, and 60 to 63 for male workers.

This change, set to take effect on January 1, 2025, has already sparked considerable discussion this year after experts proposed the adjustment. A related hashtag has garnered over 870 million views on Weibo (#延迟法定退休年龄改革#), where many users expressed their dissatisfaction with the change. “Great, I’ll get to retire in September of 2051 now,” one young worker wrote. “We start studying earlier and retire later; how can we keep up with this?”

📷 Hidden Hotel Cameras

After a Chinese blogger known as “Shadows Don’t Lie” (@影子不会说谎) recently discovered and exposed hidden cameras in the rooms of two guesthouses in Shijiazhuang, he faced significant intimidation and threats from the owners and employees, who accused him of staging the situation for attention.

However, the situation turned out to be real, and local police arrested multiple suspects responsible for installing these cameras inside these hotel rooms, which are often rented by young couples for romantic short stays. The suspects reportedly did not know the guesthouse owners and had secretly set up the cameras to profit illegally. This incident, which continues to generate discussion online, has heightened public concern over privacy protection and the integrity of the guesthouse industry, particularly as this is not the first time such issues have been revealed.

Weibo Word of the Week

The Three Questions of Patriotism

Our Weibo word of the week is 爱国三问 (àiguó sān wèn), which translates to “The Three Questions of Patriotism.” This phrase has recently gained attention on Chinese social media as it was highlighted and propagated by official media channels.

The three questions are:

1. Are you Chinese? (你是中国人吗)

2. Do you love China? (你爱中国吗)

3. Do you wish China well? (你愿意中国好吗)

These questions were originally posed in 1935 by Zhang Boling (张伯苓), the first president of the renowned Nankai University (南开大学) in Tianjin.

Today, they are being revived on Chinese social media through various videos released by official channels.

One notable video is part of a new online series produced by state media titled “Great Educators” (大教育家), which features reenactments of speeches by prominent Chinese educators. In this series, Zhang Boling’s speech, portrayed by actor Wang Ban (王斑), emphasizes the importance of unity in tumultuous times.

Rather than dwelling on differences, Zhang urged people to recognize their shared identity: they are all Chinese, they love China, and they all aspire for the country’s prosperity.

Another video features Nankai University’s current president, Chen Yulu (陈雨露), addressing students during a large event on September 21st. In his speech, Chen reiterates the three famous questions, prompting the hundreds of students in attendance to respond enthusiastically: “We are [Chinese]!” “We love [China]!” “We wish [China well]! We want China to be strong and prosperous!” This response is followed by enthusiastic applause.

Additionally, another video from the same day features a meeting between Chen Yulu and an AI version of Zhang Boling, digitally resurrected to address the students and celebrate the start of the new school year. During this ‘virtual dialogue,’ Chen informs Zhang that his ‘Three Questions of Patriotism’ have become a cherished tradition at Nankai’s annual opening ceremony.

According to Chinese state media, the students’ responses to these three questions illustrate how contemporary Chinese youth are aligning their personal aspirations with national progress. This alignment is seen as a revival of the patriotic spirit that Zhang Boling instilled in students during wartime. However, the current ‘revival’ of this sentiment appears to be largely reflected across various official channels, with limited engagement from ordinary netizens.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Popular Reads

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music7 months ago

China Music7 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight8 months ago

China Insight8 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Story of Li Jun & Liang Liang: How the Challenges of an Ordinary Chinese Couple Captivated China’s Internet