Newsletter

Weibo Watch: A Decade of What’s on Weibo

The impactful, the humorous, the surprising, the iconic – these are stories to remember as we reflect on a decade of What’s on Weibo.

Published

9 months agoon

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note

◼︎ 2. What Made an Impact

◼︎ 3. What Went Viral

◼︎ 4. What’s Iconic

◼︎ 5. What’s Controversial

◼︎ 6. What’s Shocking

◼︎ 7. What’s Funny

◼︎ 8. What Words to Know

Dear Reader,

On the night of October 16, 2010, the 22-year-old Li Qiming (李启铭) was drunk driving when he ran down two female college students roller-skating around the campus of Hebei University, killing one of them and severely injuring the other.

When he was arrested after fleeing the scene of the accident, Li Qiming showed neither concern nor remorse, and yelled: “Sue me if you dare! My Dad is Li Gang!” Li Gang was the deputy director of the local public security bureau.

“My Dad is Li Gang” (“我爸是李刚”) instantly became a popular Internet meme in China. The Hebei University incident garnered widespread attention as it touched upon several societal concerns, one of which was the mounting frustration regarding “guān èr dài” (官二代) – children of (former) government officials granted special privileges.

The phrase quickly spread far and wide, and people’s outrage started transforming into humor. The Chinese online community mop.com even organized a contest encouraging netizens to incorporate the phrase ‘my dad is Li Gang’ into classical Chinese poems, which drew thousands of entries.

Meanwhile, the Bureau of Transport in Liuzhou, a city in Guangxi, used the phrase humorously on road signs that read, “Dear friends, please drive slowly. Your father is not Li Gang.” In contrast, a Chinese company produced car stickers stating: “Don’t touch me, my dad is Li Gang” (“别碰我,我爸是李刚”).

The slogan ‘My dad is Li Gang’ popped up everywhere, both online and offline.

That year, I often felt out of the loop when my Chinese friends in Beijing would use the ‘my dad is Li Gang’ sentence – referencing both the avoidance of responsibility and abuse of power – or other online memes in their jokes and discussions, often leading to the whole table bursting out laughing. I wanted to understand this aspect of China I knew so little about.

I realized that viral stories like the Li Qiming campus crash – and how they become embedded in collective memory in the digital age – were about much more than that tragic accident alone. It was not just about guān èr dài; it also reflected the disparities in wealth, other unequal social dynamics, on-campus traffic safety concerns, the issue of drunk driving, the way the story was suppressed and shaped by official channels, and the legal system (Li received a six-year prison sentence, which many people thought was too light).

As the role played by domestic social media continued to grow in China, particularly in the early years following the launch of Sina Weibo in 2009, I began to recognize the increasing significance of digital culture and online trends as a valuable lens through which to observe China’s rapid development and changing society.

So, in 2012, I registered the domain whatsonweibo.com and started writing the first articles for What’s on Weibo in 2013. My goal was to establish a platform to report on important social trends in China. I wanted to cover not only what’s happening on Weibo but also in the broader Chinese online media world. This would help me gain a better grasp of the popular topics and the narratives that revolve around them. At the same time, I aimed to share these insights with a wider audience and create a connection between the Chinese-language and English-language online media scenes.

Ten years later, What’s on Weibo has grown into a website that has been visited by millions, garnered frequent mentions in international media, and been cited as a source in dozens of academic publications.

Chinese social media environment has seen several shifts through the past decade. The role played by Chinese social platforms, from Weibo to Wechat, from Douyin to Xiaohongshu, has become increasingly multifaceted. Enough reason to keep going and report on all the China trends that matter for the years to come.

In this special 10th anniversary newsletter, I’ve curated a selection of our most widely-read articles across various categories. I want to extend a special thank you to Miranda Barnes, who has served as a trend and news spotter for What’s on Weibo for the past six years. Throughout this time, we’ve engaged in countless discussions about trending topics, why they matter, and the diverse perspectives surrounding them. I’d also like to express my gratitude to Yiying Fan, Diandian Guo, Gabi Verberg, Cat Hanson, Boyu Xiao, Jialing Xie, Yue Xin, Chauncey Jung, Wendy Huang, and Zilan Qian, whose contributions have been so valuable to the site. Additionally, there are many others who have contributed occasionally, shared ideas, feedback, and suggestions – you know who you are – please understand that all of your input is highly appreciated.

Thanks to the support of a dedicated group of loyal readers and subscribers – you – it is possible for us to keep the site going. If you are currently not a paying subscriber, please do subscribe here to get access to all of our content and keep on receiving our Weibo Watch newsletter. I really do need your support to keep this site going for the coming years. After all, my dad is not Li Gang.

We will soon continue on our regular publishing schedule, please also follow me on X or Instagram (personal, What’s on Weibo) for the latest.

Best,

Manya

What Made an Impact

1 ◼︎ Dr. Li Wenliang |During China’s COVID years, there were a few pivotal moments when social media served as a platform for venting anger, frustration, and even despair, such as the moment the ‘Voices of April’ video flooded the internet (read). The first major social media storm revolved around Dr. Li Wenliang, one of the doctors who initially attempted to raise the alarm about the coronavirus outbreak in late December 2019. The convoluted information surrounding his tragic death in February 2020 exemplified the underlying problems in the handling of the Wuhan pneumonia outbreak in China. We first covered the story when it happened here, and then made a podcast about Dr. Li’s legacy a year later here (by the way, would you like us to do more podcasts? Let us know!)

2 ◼︎ “We Are All Fan Yusu” | Beijing migrant worker Fan Yusu became an overnight sensation when her autobiographical essay “I Am Fan Yusu” went viral on Chinese social media in late April 2017. The topics she so openly discussed in her essay, from domestic violence to social inequality, resonated with millions. After she became famous overnight, the author went into hiding and her essay was taken offline. What’s behind the sudden rise and silent disappearance of China’s biggest literary sensation of 2017? What’s on Weibo was among the first to cover her story in English and translate her full essay.

3 ◼︎ The Chained Mother | A TikTok video showing a mother of eight young children living in a small hut with an iron chain around her neck sent shockwaves across Chinese social media in January of 2022. Despite local authorities claiming that the woman was suffering from mental illness and was receiving care, online sleuths began unraveling the mystery surrounding her. This story had a significant impact in China, both online and offline, raising public awareness about the issue of human trafficking in China’s countryside and ultimately resulting in six convictions. What’s on Weibo was among the first English-language websites to report on the case, and we published multiple articles on the topic as the case unfolded in real-time. Click here for an overview of all related articles.

4 ◼︎ Justice for Lamu | The popular Tibetan Douyin vlogger Lamu died after her husband attacked her and set her on fire inside her own home. After her tragic death, Chinese netizens collectively raised their voices against domestic violence and called on authorities to do more to protect and legally empower victims of domestic abuse. Besides our article on this topic, we also did a podcast about Lamu and the aftermath.

5 ◼︎ Battle Glorified | Over the years, there have been several noteworthy Chinese films that became social media phenomena, including Wolf Warrior II and The Wandering Earth. The most significant Chinese movie of 2021 was The Battle at Lake Changjin (长津湖). This war epic not only dominated all top trending lists on Chinese social media but also became an unprecedented box office hit during a period of heightened anti-American sentiments and official narratives emphasizing China’s victory in the Korean War.

What Went Viral

Ding Zhen and the Vagrant Professor

Every now and then, ordinary yet remarkable people achieve overnight fame because vloggers capture their story, smile, or charm, resulting in viral videos. Ding Zhen and the Vagrant Professor serve as prime examples of the profound impact of sudden fame, where life is forever altered. Ding Zhen, a 20-year-old farmer from Litang in the Kham region of Tibet, unwittingly rose to online stardom after being featured in a blogger’s photography session (read more or listen to our podcast). The Vagrant Professor, a homeless man who eloquently discussed literature and philosophy on the streets of Shanghai, also experienced a dramatic change in his life after going viral on Chinese social media (learn more).

Fu Yuanhui and the Question-Asking Bitch

One moment can make someone famous and unleash a flood of memes. Chinese Olympic swimmer Fu Yuanhui became a sensation on Chinese social media after she finished third in the women’s 100m backstroke in Rio de Janeiro in 2016. More than for her swimming skills, the 20-year-old athlete was praised for her funny expressions and down-to-earth attitude (read).In 2018, a Chinese female journalist attracted the attention of netizens when she disapprovingly glanced at the woman next to her posing a question during the Two Session, and then rolled her eyes (link). Both Fu and the so-called ‘question-asking bitch’ became a source of online banter and dozens of memes.

Uncle Carpenter and the Yunnan Ice Boy

China has so many faces, and people across the country are not always aware of other people’s everyday realities. Think about the mountainous villages where society is not yet very much digitalized, where parents often leave for work in the city, leaving the elderly and the young behind. In such places, a single photo or video can turn someone into a sensation and represent a much broader reality. Think of Uncle Carpenter’s story or the Yunnan ice boy’s picture as illustrations of this trend.

Tran Tyrant and Tyrant Train Woman

Sometimes people go insta-viral due to their nasty or rude behavior. This was the case for the Shandong man who refused to give up the seat he took from another passenger. He became known as the “High-Speed Train Tyrant” (高铁霸座男 gāotiě bà zuò nán) on Chinese social media (read). Later, a female passenger’s rude behavior also went trending on Chinese social media. Some netizens figured these two ‘high-speed train tyrants’ (高铁霸座) deserve each other, creating memes putting them together (link).

What Is Iconic

You might know the chili sauce Lao Gan Ma, a household name in China. But maybe you’re less familiar with the story behind the sauce and its founder, which has inspired millions of people and has made ‘Old Godmother’ Tao Huabi a notable figure in Chinese contemporary culture today. For many, the successful businesswoman and ‘chili sauce queen’ is an embodiment of the ‘Chinese dream.’

From innocent children’s cartoon via subculture icon to banned topic; Peppa Pig has had a rollercoaster ride in China. In 2018, Peppa Pig became a subversive symbol to a Chinese online youth subculture dubbed ‘shehuiren‘ (社会人), literally ‘society people’, which is a group of young adults that is anti-establishment and somewhat ‘punk’ in their own way; going against mainstream values and, as state media outlet Global Times put it, are “the antithesis of the young generation the Party tries to cultivate.”

Perhaps you’ve seen the famous fighting scenes of Tarantino’s Kill Bill, know who Bruce Lee is, and have watched a kung fu movie at least once in your life – but do you know the Shaw Brothers enterprise? It’s the production company that gave martial art its worldly success on the big screen. Shaw Brothers made everybody go ‘kung fu fighting’, creating a unique Chinese cinema. Run Shaw, the last of the Shaw Brothers, passed away on Jan 7th 2014 at the age of 107, after which we published this short history of the Shaw Brothers & Chinese cinema.

What’s Controversial

◼︎ “Seriously China?!” | In 2016, a Chinese ad campaign for washing detergent brand Qiaobi (俏比) that aired on TV and in cinemas started making its rounds on the internet, drawing much controversy for being “completely racist”. Read more.

◼︎ “Too Loud, Too Rude” | “They’re loud and rude, and spit on the floor.” An article in Swiss newspaper Heute reported about locals being digruntled with Chinese tourists, leading to Rigi Rails introducing special coaches for Asian tourists. The news triggered mixed reactions amongst Weibo’s netizens. Read more.

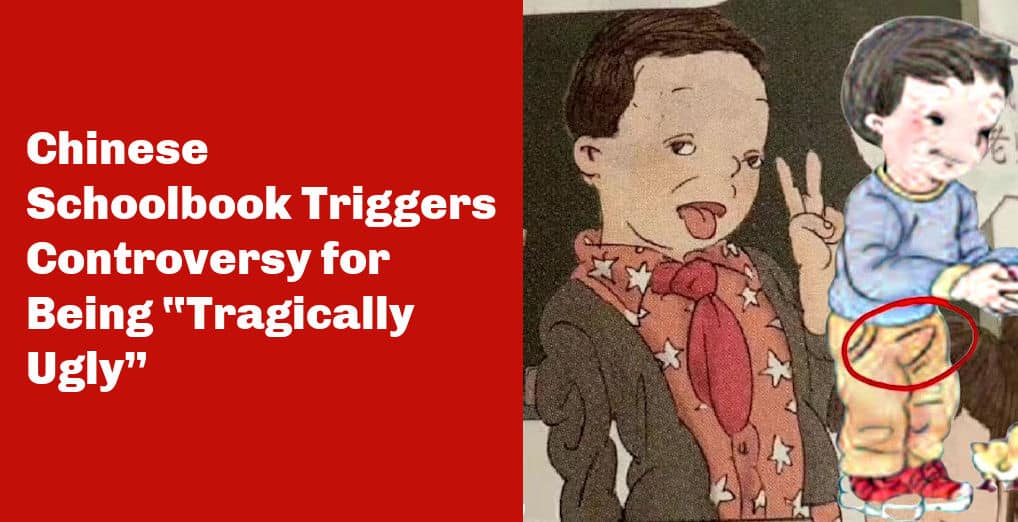

◼︎ Math Schoolbook Gate | It’s the textbook illustration controversy that dominated Chinese social media in Spring of 2022. After parents notes that the drawings in their children’s school math textbooks were “displeasing,” the entire Chinese internet weighed in and concluded that the overall design was just strange and “tragically ugly.” The controversy had some serious consequences for the publisher. Read here.

◼︎ Controversial Death | Some netizens called it one of the biggest controversies of the year. The death of the 29-year-old environmentalist Lei Yang while in police custody sparked online outrage in 2016, with many connecting this fatality to police brutality. Lei’s wife stepped forward, demanding answers from Beijing authorities on the circumstances surrounding her husband’s death. Read here.

◼︎ Marketing Controversy | There’ve been many China marketing disasters throughout the years, often relating to foreign brands in politically tense times (think of all the brands getting into trouble for listing Hong Kong separately from China during the Hong Kong protests). The 2018 D&G controversy is a classic one that completely struck a wrong chord. It started with a promotional video that was deemed racist, got really messy when screenshots went viral of a China-bashing online conversation with the alleged Stefano Gabbana, started snowballing when D&G claimed the account was hacked, and ended with the cancellation of Dolce & Gabbana’s big Shanghai show. Read here.

What’s Shocking

▶︎ An incident in which a Shanghai man, who was thought to be dead, was taken to a funeral home before he was found to be alive became a big topic on Chinese social media. Link.

▶︎ Chinese underworld kingpin Zhao Fuqiang turned his Shanghai “Little Red Mansion” into a hell on earth for dozens of women who were forced into a life of sex work within his organized crime network. Link.

▶︎ An outburst of violence against female customers at a restaurant in Tangshan sent shockwaves across Chinese social media in 2022. Link.

▶︎ A man killed his wife in Shanxi in the middle of the street, yet nobody intervened. Link.

▶︎ Following the announcement of a positive Covid test result within a building in Shanghai’s Yangpu District, a collective exodus ensued as people wanted to avoid getting locked inside. Link.

What’s Funny

▶︎ Lego for Adults | A man who spent three days and three nights working on a Nick the Fox Lego sculpture was left aghast when his masterwork was pushed over by a little kid – just within an hour after it was first displayed.

▶︎ Avenging the Grannies | Over the years, there have been numerous stories related to China’s notorious dancing grannies, including incidents where stressed-out students were disrupted by their loud music. Thanks to this device that went viral in 2021, neighbors have a way to respond to the local square dancing group by secretly shutting down their music.

▶︎ Rabbit gets Roasted | A zodiac stamp issued by China Post on the occasion of the Year of the Rabbit became an unexpected viral hit in January of 2023. Not because of its pretty design, but because the red-eyed blue rabbit triggered controversy for being “monster-like” and “nightmare fuel.” It was not the only rabbit getting roasted!

▶︎ Cute Couple | While everybody was watching whether or not Nancy Pelosi would visit Taiwan in August of 2022, there was still time for some online banter amid growing tensions: Chinese netizens created a fantasy love affair between U.S. House speaker Pelosi and Chinese Global Times commentator Hu Xijin.

▶︎ Catch of the Day | It does not matter if you’re old or young, shrimp or fish – you couldn’t escape China’s zero-covid policy. These fish in Xiamen had to have their daily Covid tests, too.

Weibo Words to Remember

Green Tea Bitch | In the spring of 2013, a new term was launched over the Chinese Internet: ‘Green Tea Bitch’ (绿茶婊). According to Chinese netizens, the term is used to describe ambitious women who “pretend to be very innocent.”

Russia, the ‘Weak Goose’ | In 2022, multiple Chinese (military) bloggers started using the ‘weak goose’ (菜鹅) term in light of Russia’s fading victory, signaling a shift in online sentiments regarding Russia’s position and its military competence.

Little Sheep People | As many people faced Covid-related discrimination in China after testing positive in early 2022, social media users started speaking out against popular (online) language that refers to Covid patients as ‘sheep,’ saying the way people talk about the virus is worsening existing stigmatization.

Hard Isolation | The word popped up on Chinese social media in April of 2022 after some Shanghai netizens posted photos of fences being set up around their community building to keep residents from walking out.

Involution | Since recent years, this word has come to be used to represent the competitive circumstances in academic or professional settings in China where individuals are compelled to overwork because of the standard raised by their peers who appear to be even more hardworking.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Newsletter

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

The future is here, but it looks different than we expected. This Weibo Watch covers driverless taxis and other noteworthy, popular topics.

Published

4 days agoon

July 23, 2024

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #33

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – The future is here

◼︎ 2. What’s New and Noteworthy – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s Remarkable – A panicked mum goes to extremes

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – The passing of Cheng Peipei

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Virtual news anchors

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – Bye bye, Biden

Dear Reader,

The future is here, and it is all unfolding so much differently than we could have imagined.

Scrolling through Douyin and Weibo’s video feeds recently, there are hundreds of videos about China’s self-driving taxi revolution. The wonder and excitement over the unmanned cabs is not surprising – it is the biggest thing happening in China’s taxi industry since ride-hailing apps Didi, Kuaidi, and Uber first entered the Chinese market over a decade ago.

Luobo Kuaipao (萝卜快跑) by Baidu, called ‘Apollo Go’ in English, is the ‘robotaxi’ ride-hailing platform that is now generating the most attention online. The concept is simple: customers order the taxi via the app and enter their destination, it arrives at the meeting point, and via a panel on the side of the car, the customer inserts the last four digits of their phone number. The door then automatically opens, and they can get in the car, which will take them to where they want to go. The car is private, and the price is comparable to ride-sharing fees, but then cheaper.

There is an additional benefit: the cars are equipped with a “smart cockpit”, allowing passengers to start their journey by tapping the screen in front of them, selecting a podcast or their favorite music, controlling the air-conditioning, and watching the traffic while en route.

Currently, Luobo Kuaipao has some 500 robotaxis operating without safety drivers in Wuhan, now the world’s largest city for driverless taxis. Baidu plans to expand this fleet with an additional 1,000 robotaxis soon. Shanghai will also launch a public testing program for driverless taxi services by SAIC in the upcoming week.1

Across China, at least 16 cities are now testing self-driving vehicles, with at least 19 Chinese car manufacturers competing for global leadership. Nationwide, 20 provinces have already released policies and regulations for autonomous driving.23

In many bigger Chinese cities, smart autonomous vehicles are already part of daily life. For years now, autonomous cleaning cars have been a common sight in popular tourist spots. I remember seeing a cute little car working hard to clean the area around the Terracotta Warrior museum in Xi’an in 2019. There are also self-driving tourist shuttles, driverless trucks operating between Beijing and Tianjin, and AI-driven service carts that precisely know where crowds gather during lunch breaks, stop when people wave, and process mobile payments for hamburgers or chicken salads on the spot.

So far, so ‘futuristic.’

But it’s not all roses. Besides the many enthusiastic videos taken by Chinese riders posting their experiences of taking an unmanned, self-driving taxi for the very first time, the emergence and rising popularity of robotaxis is also leading to worries, complaints, and aggravation.

A commonly heard objection to the unmanned taxis is that they are taking away jobs in the taxi industry. Perhaps even more so than when ChatGPT first emerged, the question of AI replacing people rather than serving them is frequently popping up, with taxi drivers fearing they’ll lose their jobs as robotaxis spread throughout China. These worries can still be countered by the numbers. After all, Wuhan has more than 100,000 registered ride-hailing cars, and Luobo Kuaipao holds just around 0.40% of the market – an insignificant number. 4 But with the rise of the industry, including its competitive prices, that number is bound to change.

Another far more unexpected concern about the rise of China’s robotaxis is that they’re causing chaos in the streets by being ‘too polite.’ These autonomous taxis are trained to follow the traffic rules and act civilized in traffic – something that seems out of place in some areas, where not following the rules almost seems like a rule.

By staying in the right lane, stopping for red lights, and giving priority to other cars, pedestrians, and animals, Chinese robotaxis are causing road congestion and sometimes accidents. They often struggle with complex traffic situations; for example, a viral video showed two Luobo Kuaipao cars waiting for each other to move, holding up traffic. In Wuhan, where drivers are known for their aggressive driving style, these autonomous cars face additional challenges. They strictly follow traffic laws and are not accustomed to pushing their way into traffic, which can lead to long waits for simple turns or merges, causing delays for other drivers.

This behavior has earned them the nickname ‘Sháo Luóbo’ (勺萝卜, “silly radish”), suggesting they are sluggish, or dumb. Although Luobo Kuaipao translates to ‘Radish Runs Fast’ or ‘Carrot Run,’ implying speed and efficiency, the reality is quite different.

Also unexpected is how ‘driverless’ is not what you might have thought it is; because every car still has a “safety operator” who is remotely monitoring it from another location. One person can monitor 10 cars or even more, but they’re allegedly penalized if they close their eyes for more than three seconds.5 Videos and pictures from these robotaxi headquarters sometimes look like old-fashioned game halls or internet cafes.

Complaints about Luobo Kuaipao not being as modern as people hoped and not being as assertive as they thought ultimately boil down to a clash of cultures. Luobo Kuaipao is made in China, but it’s not programmed with the personality and ways of a Wuhan taxi driver. In the end, Wuhan drivers will need to learn from Luobo Kuaipao, and Luobo Kuaipao will need to learn from Wuhan traffic. One side will learn to become more ‘polite,’ while the other will need to add some ‘aggression’ in order to mix in with traffic.

As ‘silly’ as Luobo Kuaipao may seem now, let’s not forget that everything starts small – we all began in diapers. Nothing significant ever came without humble beginnings. The future is here, but what we consider truly ‘futuristic’ will perhaps always be a vision for the days to come.

Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang have contributed to the compilation and interpretation of some topics featured in this week’s newsletter. As always, if you have any observations or ideas you’d like to share, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me.

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

References:

1 Wu Qingqing 吴青青. 2024. “The Luobo Kuaipao Versus Tesla War”[萝卜快跑,与特斯拉终有一战].” Auto Business Review (汽车商业评论), July 18 https://inabr.com/news/19693 [Accessed July 22, 2024].

2 Bradsher, Keith. 2014. “China Is Testing More Driverless Cars Than Any Other Country.” New York Times, June 14 https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/13/business/china-driverless-cars.html [Accessed July 22, 2024].

3 Qi Xu 齐旭. 2024. “Which City is China’s First City for Autonomous Driving? [谁是中国自动驾驶“第一城”?]” China Electronics News 中国电子报, July 16 https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20240716A00W2N00?suid=&media_id= [Accessed July 22, 2024].

4 Wu Qingqing 吴青青. “The Luobo Kuaipao Versus Tesla War.”

5 Jones, Phil. 2014. “Behind Driverless Cars – The Safety Operators Who Can’t Close Their Eyes[无人驾驶车背后,是无法闭眼的安全员].” The Paper, July 19 https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_28124126 [Accessed July 22, 2024].

What’s New

“As smooth as a flying bullet” | The assassination attempt on former US President Trump at a Pennsylvania campaign event also became a major topic on Chinese social media, where Trump’s swift reaction and defiant gesture after the shooting have not only sparked discussions but also fueled the “Comrade Trump” meme machine.

Park with a view | “The ‘sea in Ditan Park’ is a perfect example of how Xiaohongshu netizens use their imagination to change the world,” a recent viral post on Weibo said. This seaview spot in the Beijing public park has become a new ‘check-in spot’ among Chinese Xiaohongshu users and influencers.

From Hollywood to Beijing | For the Dutch national broadcaster’s summer series ‘From Hollywood to Bollywood,’ I spoke about the Chinese blockbuster Battle at Lake Changjin (2021) this week. This spectacular war film depicts the story of Chinese troops during the massive Battle of the Chosin Reservoir in the Korean War, where they encircled and pushed back American forces. The film is an impressive visual spectacle, but it’s a landmark movie in other aspects as well. Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, China is striving to become a global powerhouse in the film industry. At the same time, this film also helped shape new narratives of the Korean War that foster patriotism. Dutch readers can listen to or watch the entire conversation via the link. If you’re interested in learning more about this topic but not that good at understanding Dutch—nobody’s blaming you—check out this article on WoW from our archive.

What’s Trending

JULY 11

🛢️🍳 Cooking Oil Scandal | A major news topic that’s been fermenting over the past month is the revelation that some cooking oil transport trucks in China are also being used for transporting industrial oil. The issue went trending after a publication by Beijing News authored by investigative journalist Han Futao (韩福涛) on July 2, which detailed how the same tanks were used for transporting both edible oils like soybean oil and chemical oils like kerosene without any cleaning process. The food safety scandal sparked outrage online and led to people meticulously tracking the whereabouts of oil tankers and how they operate, while various tanker companies came forward to provide clarity on their procedures. The incident has raised significant awareness about the potential misuse of tankers and intensified concerns about food safety in China.

JULY 15

🚗 Trump Photo Copyrights | After the Trump rally shooting went viral across Chinese media, another trending hashtag emerged regarding the copyright of the iconic ‘raised fist photo,’ shot by award-winning photographer Evan Vucci. Chinese online sources attributed the photo’s rights to the photo agency “Visual China” (视觉中国), allegedly charging 2100 yuan ($288) per use on social media, with threats of lawsuits for unauthorized use. This sparked debates over copyright ownership, as Evan Vucci was not mentioned. In the past, the same company triggered controversy for claiming copyright for an image of the Chinese national flag. They were also sued by a Chinese photographer for claiming ownership of 173 of his photos. Visual China later clarified that they, as a partner of AP, only have distribution rights but do not own the Trump photo.

JULY 16

🌧️ Floods | Thousands of households across China have been affected by floods recently, from Sichuan to Hunan, from Henan to Shaanxi. The city of Xiangyang in Hubei is one such affected area, which experienced its strongest rainfall since the start of the flood season. Some areas nearby broke single day rainfall records, with cars in the streets being swept away by the water. In Henan, floods forced over 100,000 people to evacuate their homes, according to state media. The floods have been catastrophic, especially for farmers, leaving widespread devastation.

JULY 19

🏥 Wenzhou Doctor Killed | A vicious attack on a doctor at the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University has gone viral this week, sending shockwaves across Chinese social media. The incident occurred on the afternoon of July 19, when a man suddenly attacked and stabbed Dr. Li Sheng (李晟), who was on duty in the hospital’s cardiology department. The attacker subsequently jumped off the building. Despite extensive rescue efforts, Li succumbed to his injuries that night. The incident has sparked outrage, particularly in light of several recent stabbing incidents and the ongoing issue of patient-doctor violence, leading many netizens to call for improved security measures in hospitals. Tributes to Dr. Li Sheng online describe him as a man fully dedicated to his work and patients. China’s National Health Commission condemned the attack, stating there is zero tolerance for any form of violence against medical personnel.

JULY 20

🌉 Collapsed Bridge | After heavy rain and flash floods, a highway bridge that had been in use for less than six years in Shangluo, Shaanxi Province, collapsed on July 19th, causing 25 vehicles to fall into the river. While rescue efforts were still underway, the incident has resulted in 12 known deaths and 31 missing. The past weekend, two missing vehicles were found downstream, 4 kilometers from the collapse site. More than 700 professionals from various emergency services, along with over 1,500 local officials and residents, have been mobilized for search and rescue operations.

JULY 17

🔥🚒 Shopping Mall Fire | Videos of a terrible fire at the 14-story Jiuding Department Store in Zigong, Sichuan, spread on Chinese social media on Wednesday night. Initially, the death toll stood at 8, but it later emerged that at least 16 people lost their lives in the flames despite extensive rescue efforts by firefighters. Thirty-nine people were hospitalized. The fire, now known as the “7·17 major fire accident” (“7·17重大火灾事故”), is suspected to be linked to ongoing construction work.

JULY 21

🏅🧳 Olympic Suitcase Fever | Just a few days before the start of the Olympic Games in Paris, and the Olympic fever is noticeable on Chinese social media. Chinese state media have issued phone wallpaper featuring Olympic athletes. However, what recently attracted the most attention are the suitcases used by Chinese athletes traveling to Paris. These suitcases, called “Ying Yong” (英俑), were designed exclusively for the Chinese sports delegation by a company in Hangzhou. The design is themed around the Terracotta Warriors, using red and black and featuring other details inspired by the Terracotta Army.

JULY 22

🏫 Professor Mi | A story about renowned Chinese professor Wang Guiyan (王贵元) has been blowing up on Chinese social media after he was accused of sexual misconduct by a former female doctoral student. She made these allegations through an online video against the professor, who also served as the Party Secretary and Vice Dean of the School of Liberal Arts at Renmin University of China. On July 22, the university responded to the allegations and stated that their investigations found them to be true. As a result, Wang has been expelled from the Party, his professorship has been revoked, his qualification as a graduate supervisor has been canceled, he has been removed from his teaching position at Renmin University, and his employment has been terminated.🔚

What’s Noteworthy

A mother who lost her child while shopping in a mall in Shiyan, Hubei, went to extreme measures to get her child back as soon as possible. On July 19, the panicked woman triggered the mall alarm by smashing the displays at a jewelry store with a fire extinguisher. This caused the mall to shut all its doors and prompted a police squad to arrive within minutes. A viral video of the incident showed the mother shouting for help as she broke glass displays. The child was soon located.

In the past, there have been various stories about children being kidnapped and having their appearances changed quickly, making it much more challenging to find them. One such story from 2018 showed the speed at which human traffickers work: a 5-year-old girl went missing from a local playground at 14:41, and it later became clear that the little girl, taken away in a minivan with a middle-aged woman and another child, departed her city by train just fifteen minutes later. She got off at a station some 60 miles away with changed clothes and a shaved head (read here).

Although the mother may have thought she did the right thing by smashing the displays to get help to locate her child as soon as possible, she is also receiving a lot of criticism online. Commenters argue that the woman should have never lost sight of her child in the first place, let alone vandalized mall property. The jewelry store also had nothing to do with the child going missing. The local police stated that the woman’s actions would be handled according to public security regulations, so she can expect to pay a fine and compensation to the store.

Meanwhile, there are also people who sympathize with the mother, as they don’t want to imagine what could have happened to the child if standard, slower procedures were followed. However, state media outlets warn others not to take the woman as an example.

What’s Popular

She was known as the heroine and villain of Wuxia movies, the queen of the swords, and a martial arts diva. Hong Kong actress Cheng Pei-pei (郑佩佩) trended all day on Chinese social media after news broke that she had died at the age of 78.

The Shanghai-born Cheng had a background in ballet and modern dance—skills she incorporated into the fight choreographies of the martial arts films she made for the Shaw Brothers in the 1960s and 70s. She later moved to the United States. Cheng gained international fame when she starred as Jade Fox in Ang Lee’s “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” in 2000. Cheng suffered from Corticobasal degeneration (CBD), which shares some similarities with Parkinson’s disease.

On social media, Cheng is remembered not only by other actors and celebrities but also by many regular netizens who see her passing as a major loss to the Chinese film industry. (To read more about the Shaw Brothers & Chinese cinema, check our article here.)

What’s Memorable

For this pick from the archive, and in the context of the future being here, we revisit a 2023 article about Chinese state media introducing a virtual news anchor. While the first virtual presenter was introduced in 2019, People’s Daily introduced Ren Xiaorong (任小融) as a virtual presenter/news anchor in 2023. Although virtual news presenters are not yet the norm, this is a trend that is still developing. For example, this week, China’s Military News Agency also launched their virtual anchor to improve communication efficiency.

Weibo Word of the Week

Bye Bye Biden | Our Weibo phrase of the week is Bye Bye Biden (bài bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登).

As news of Biden dropping out of the presidential race went viral on Weibo early Monday local time, it’s time to reflect on some of the popular nicknames and phrases given to US President Joe Biden on Chinese social media.

🔹 Biden in Chinese: Bàidēng 拜登

Biden in Chinese is generally written pronounced and written as Bàidēng 拜登. Although the character 拜 (bài) means “to pay respect, to worship” and 登 (dēng) means “to ascend, to climb,” they’re used here primarily for their phonetic similarity. The characters chosen are neutral to avoid any negative implications in the official translation of Biden’s name.

Why are non-Chinese names translated into Chinese at all? With English and Chinese being vastly different languages with entirely different phonetics and scripts, most Chinese people find it difficult to pronounce a foreign name written in English. Writing foreign names in Chinese not only standardizes them but also makes pronunciation and memorization easier for Chinese speakers.

🔹 Bye Biden: Bài Bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登

Because Biden is Bàidēng, and the Chinese for ‘bye bye’ is written as bài bài 拜拜, some netizens quickly created the wordplay “bài bài Bàidēng” 拜拜拜登 (“bye bye Biden”) upon hearing that Biden would not seek reelection. Try saying it out loud—it almost sounds like you’re stammering.

🔹 Old Joe: Lǎo Dēng Dēng 老登登

Another common farewell greeting to Biden seen online is “bài bài lǎo dēng dēng” 拜拜老登登, which sounds cute due to the repetition of sounds.

“Old Biden” or “lǎo dēng dēng” 老登登 is a common online nickname for Biden in Chinese. The reduplication of the 登 (dēng) makes it sound playful and affectionate, while the “old” prefix is commonly used when referring to someone older. It’s similar to calling someone “Old Joe” in English.

🔹 Biden Variations: 拜灯, 白等, 败蹬

Let’s look at some other ways Biden is nicknamed online:

Besides the official way of writing Biden with the 拜登 Bàidēng characters, there are also other variations:

拜灯: bài dēng

白等: bái děng

败蹬: bài dèng

These alternative ways of writing Biden’s name are not neutral. Although the first variation is not necessarily negative (using the formal Biden 拜 bài character but with ‘Light’ 灯 dēng instead of the other 登 ‘dēng’), the other two variations are usually used in more negative contexts.

In 白等 (bái děng), the first character 白 (bái) means “white,” which can evoke associations with old age due to white hair (白发). The character 等 (děng) means “to wait,” and the combination can imply being old and sluggish.

败蹬 (bài dèng) is typically used by netizens to reflect negative sentiments towards the American president. The characters separately mean 败 (bài): “to be defeated,” “to fail,” and 蹬 (dèng): “to step on,” “to kick.” This would never be used by official media and is also often used by netizens to circumvent censorship around a Biden-related topic.

🔹 Revive the Country Biden: Bài Zhènhuá 拜振华

Then there is 拜振华 Bài Zhènhuá: revive the country Biden

In recent years, Biden has come to be referred to with the Chinese nickname “Revive the Country Biden,” also translatable as ‘Thriving China Biden’. This nickname has circulated online since 2020 and matches one previously given to former President Trump, namely “Build the Country Trump” (Chuān Jiànguó 川建国).

The idea behind these humorous monikers is that both Trump and Biden are seen as benefitting China by doing a poor job in running the United States and dealing with China.

🔹 Sleepy King: Shuì wáng 睡王

Shuì wáng 睡王, Sleepy King, is another common nickname, similar to the English “Sleepy Joe.” During and after the 2020 American presidential elections, there were numerous discussions on Chinese social media about ‘Trump versus Biden.’ Many saw it as a contest between the ‘King of Knowing’ (懂王) and the ‘Sleepy King’ (睡王).

These nicknames were attributed to Trump, who frequently boasted about his unparalleled understanding of various matters, and Biden, who gained notoriety for being older and tired. Viral videos, some manipulated, showed him nodding off or seemingly disoriented. The name ‘Sleepy King’ then stuck.

🔹 Grandpa Biden: Bài Yéyé 拜爷爷

Throughout the years, Biden has also been nicknamed Bài yéyé 拜爷爷, “Grandpa Biden.” This is usually more affectionate, though it emphasizes his age—Trump is not much younger than Biden and is not nicknamed ‘Grandpa Trump.’

Another similar nickname is lǎo bái 老白, “Old White,” referring to Biden’s age and white hair. 白 (bái, white) can also be a surname in Chinese. This nickname makes it seem like Biden is an old, familiar friend.

On Weibo, many speculate that American Vice President Kamala Harris will be the new candidate for the Democrats, especially since she’s been endorsed by Biden. Many have little confidence that she can compete against Trump. Her Chinese name is Kǎmǎlā Hālǐsī 卡玛拉·哈里斯, commonly referred to as ‘Harris’ (Hālǐsī).

In light of the latest developments, some netizens jokingly write: “Bye bye Biden, Ha ha ha, Harris.” (Bài bài, Bàidēng. Hā hā hā, Hālǐsī 拜拜,拜登。 哈哈哈,哈里斯). With a new Democratic candidate entering the presidential race, we can expect a fresh batch of creative nicknames to join the mix on Chinese social media.

Want to read more? Also read: Why Trump has Two Different Names in Chinese.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

China Memes & Viral

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

This week, Chinese netizens discussed subway seat confrontations, a shocking public stabbing, and Hu Youping’s heroism. Also: more trending topics, from hallucinogenic mushrooms to traveling pandas and reactions to the Biden vs. Trump debate.

Published

3 weeks agoon

July 7, 2024

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #32

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Get up, stand up

◼︎ 2. What’s New and Noteworthy – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s Remarkable – Seeing little people

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – Wild Child: missing in action

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Bystander effect

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – “City bu City”

Dear Reader,

Over the past few weeks, there has been a lot of discussion on Chinese social media about young people refusing to give up their seats for older people on the subway, sometimes leading to explosive situations.

On June 16, security was called when a young man on a Shenyang subway crumbled after an old man demanded that he’d give up his seat for him. In a video of the incident, which soon went viral, the young man can be heard screaming: “Are you giving me money? No? Then don’t bother me! I’m just happy to be sitting here. What’s wrong with me grabbing a seat?

Another subway incident went trending a week later. On June 24, a 65-year-old man started harassing a young woman on Beijing Subway Line 10 after she refused to give up his seat to him. The man became aggressive, started slapping the woman and put his cane in between her legs, trying to force her to stand up. The incident, which was filmed by other passengers, caused outrage on social media and the man was later detained by Beijing police.

A day later, in Wuhan, an elderly man and a young woman also got into an altercation that was caught on camera. After female passenger took the only available seat during morning rush hour on Line 2, the man reminded her that she should give up her seat out of respect for the elderly. “Why should I?” she asked: “I don’t owe you anything. I work overtime until 12:00 at night every day, and now you expect me to give up my seat during the morning rush hour?”

These incidents have sparked discussions about how people feel about these situations. In China, where respect for the elderly is deeply ingrained in the culture, should you give up your seat to the elderly on public transport because it is your duty, or is it just a personal choice? In an online poll held by Sina News, over 93% of respondents said they felt it was not their duty to give up their seat but a personal choice—a matter of courtesy.

“As long as you’re not sitting in a priority seat, you don’t have to give up your seat,” a top comment said. “It’s not easy being working class.” Many people echoed this sentiment, siding with the younger people who are facing their own tough struggles in China today. “I’d advise the elderly not to crowd public transport during the morning and evening rush hour,” another popular comment said, receiving thousands of likes.

These discussions signal a social shift: “When the topic comes up about young people not giving up their seats for the elderly, have you ever considered that these young people have been working all day? If you feel so strongly about it being your duty, how about you call a taxi for the elderly yourself?”

While many commenters expressed that people are not obliged to give up their seats to others, some, including pregnant women, complained about the overall reluctance of other passengers to give up their seats for them. “It feels like everybody is tired,” one Weibo user wrote.

Standing By

Another noteworthy discussion on Chinese social media recently was not about sitting down but about standing by. In a stabbing incident caught on camera by bystanders, a man locally known as “Bag-Clutching Brother” (夹包哥) was killed in the city of Songyuan in China’s Jilin province on June 30. His real name was Mr. Zhao, but he earned the nickname “Jiabaoge” (夹包哥, “Brother Clutch Bag”) for his eccentric square dancing while clutching a bag.

A video of the horrific incident shows Mr. Zhao happily dancing in a public square in Songyuan, with dozens of people present, when a man suddenly draws a knife and starts stabbing him. As the crowd watches on, the attack continues. Moments later, Mr. Zhao can be seen lying in a puddle of blood while still being attacked. Bystanders did not intervene. The attacker, a local drunk who did not even know “Brother Clutch Bag,” was detained by police. Zhao died of his injuries.

The incident caused a shock wave on social media. “They all stand in a circle and watch,” a typical comment said. “Not one of them stepped forward to help.” Some people called the onlookers “cold and detached” (“冷漠围观”).

While many suggest the onlookers are selfish and too preoccupied with filming to actually intervene, others suggested they were just scared to face the consequences of intervening.

There is a complex interplay of factors associated with the likelihood of people intervening when witnessing a crime or other emergency. Research points out that the higher the levels of fear among bystanders, the less likely they are to intervene. The more they perceive themselves as strong, the more likely they are to help. Additionally, the more people witnessing an emergency, the less personal responsibility is felt, reducing the chances of intervention.

As a victim, you might be more fortunate if just one person sees your predicament—and comes to your aid—than if a hundred people look on and do nothing.

Hu Youping

This issue perhaps also played a role in a third noteworthy topic that became a major trend recently, which I also wanted to mention here. It concerns the death and honoring of Ms Hu Youping (胡友平). Hu Youping, a 54-year-old school bus attendant, stepped in to help when a Japanese mother and child were attacked by a man with a knife at a school bus stop in Suzhou on June 24.

Hu was working that day when, around 4 pm, someone wielding a knife started attacking people at the bus stop near Xindi Center on Tayuan Road. As she rushed forward to stop the attacker, she was stabbed multiple times—one of the stabs hit her heart. On June 26, two days after the incident, Hu succumbed to her injuries.

The story of Hu Youping is remarkable on many levels. Not only was she brave, but she also intervened during a time when multiple stabbing incidents were making the news (also see: Jilin stabbings). Her courage became the focus of Chinese media reports about the Suzhou stabbing, diverting attention from the suspect’s motivations and discussions questioning China’s public safety. Adding to the story is that Hu protected a Japanese mother and child, which, in the context of Sino-Japanese tensions, reinforced her selflessness.

Hu’s face was suddenly everywhere. Netizens praised her kindness, and state media honored her bravery. As she officially received the title of “Model of Righteousness,” she was exemplified as embodying the kindness and courage of the Chinese people by local authorities. The Tianjin Radio and Television Tower even lit up in honor of Hu Youping, projecting her portrait on the side of the building.

Hu Youping is seen as a selfless heroine. Her story is not just propagated by official channels, it also resonates with the people. “People like Ms. Hu Youping and other heroes are remarkable, not only for their willingness to sacrifice themselves but also for inspiring those around them,” one Weibo blogger wrote.

Perhaps Hu Youping is the role model people need at this time, when so many stories about a lack of altruism, conflicting values, and moral crises are trending on social media. She was not necessarily an extraordinary person; she was a normal, kind-hearted and hard-working woman who would not stand by while seeing people in trouble.

However, while Hu Youping’s bravery is inspiring, her courage also serves as a cautionary tale. In one thread about the passive crowds watching Mr. Zhao get killed, commenters wrote: “Look what happened to Ms. Hu Youping. She got killed while bravely intervening, so who would dare to step in here?”

Her courage and ensuing death have ignited a realistic debate on what helping others may look like when confronting an armed attacker directly is not an option: “If someone is attacking with a knife and you are unarmed, your only option is to run. If you can help others to run with you, you are already a hero.”

In the end, Hu Youping triggers discussions on kindness, fearlessness, and doing what’s right. At a time when the social moral compass seems adrift, people like Hu help recalibrate it. Whether it means standing up or sitting down, stepping in or getting out, it’s always best to follow that personal moral compass regardless of what others do. Sometimes, that might mean sitting down when you need to rest, knowing that taking care of yourself is just as important. At other times, it means standing up when nobody else does, and rising not because it’s your duty, but because you know it’s the right thing to do.

Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang have helped compile some of the topics mentioned in this week’s newsletter. As always, please do not hesitate to reach out if you’d like to share something you’ve spotted or share your ideas with me.

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

What’s New

Humble Prodigy or Deceptive Impostor? | It’s rare for a math competition to become the focus of nationwide attention in China. But since 17-year-old vocational school student Jiang Ping made it to the top 12 among contestants from prestigious universities worldwide, her humble background and outstanding achievement sparked debates and triggered rumors.

“Scared to Intervene” | In a shocking incident caught on camera, a well-known Songyuan resident nicknamed “Brother Clutch Bag” was tragically stabbed to death. On Weibo, people have reacted with disbelief.

Another One Bites the Dust | Li Shangfu allegedly “took advantage of his position to seek benefits for others” and received large sums of money.

What’s Trending

JUNE 26

🇺🇸 Biden vs Trump | Just like in the rest of the world, Biden and Trump’s presidential debate became a hot topic on Chinese social media. Chinese America watchers harshly criticized the debate, describing it as a race between a “madman and a senile patient.” Others perceived the overall energy and quality of the debate as indicative of troubled times for America and see the presidential campaign as a sign of Western democracy falling behind. Many commenters suggest that it does not really matter for China who becomes president, as both candidates are expected to adopt a tough stance on China. Nonetheless, there were various posts indicating a preference for Trump because he generates more memes and jokes on Chinese social media and is “more fun to watch.”

JUNE 29

🐼 From Sichuan to San Diego | They are the first set of pandas to make their way to the U.S. in 21 years: Yun Chuan (云川) and Xin Bao (鑫宝) safely arrived in San Diego on June 28 after a long flight from China. Their caretakers in Sichuan had to say goodbye to them for a loan period of at least ten years. On Chinese social media, many commenters expressed sadness about the pandas leaving China, wondering if their American adventure is really in their best interest.”

JUNE 30

🚀 Accidental Rocket | Was it a plane? Was it a meteor? Videos of an explosion in the hills near Gongyi City in Henan recently went viral (link). The huge impact was not caused by a meteor; it was a rocket. While performing a ground test, the Chinese rocket by space startup Space Pioneer (天兵科技) was accidentally launched and crashed near a residential area. There were no reports of casualties. A few days later, Space Pioneer sincerely apologized and promised that the company would compensate anyone who suffered property damage due to the test failure. The incident has sparked questions on why a private enterprise was able to test out rockets in Gongyi in the first place.

JULY 1

🏸 Zhang Zhijie Dies | On June 30, the young Chinese badminton player Zhang Zhijie (张志杰) collapsed and convulsed during a game in Indonesia. Videos of the incident (link) showed how it took about 40 seconds before medics arrived to attend to him. After being rushed to the hospital, the 17-year-old player from Jiaxing, Zhejiang, passed away. According to Indonesia’s badminton association, Zhang died due to sudden cardiac arrest. On Weibo, a hashtag about Zhang’s death garnered over 560 million views (#张志杰去世#) since late June. Zhang’s sister shared her grief and shock about her brother’s death on her Weibo account. Zhang’s mother was so overcome with grief that she had to be temporarily hospitalized earlier this week. Zhang’s family is now in Indonesia, seeking more clarity on his death and holding those responsible accountable.

JULY 2

🚗 Molly and Mr. Musk | “Hello Mr. Musk, I’m Molly from China. I have a question about your car. When I draw a picture, sometimes it will disappear like this. You see it? So can you fix it? Thank you.” Recently, a 7-year-old girl from Beijing named Molly recorded a video for Elon Musk, in which she complained in English about a bug in Tesla’s sketchpad: when adding a new stroke to her drawing, Molly found that previous strokes would sometimes disappear. In response, Musk replied to her on the X platform, “Sure.” The little exchange generated a lot of attention for Molly on Chinese social media, where the little girl was applauded for how she managed to address an issue with her drawing pad directly with Mr. Musk himself.

JULY 6

🌊 Dongting Floods | A dike of Dongting Lake in Yueyang, Hunan Province, burst on Friday afternoon, causing serious flooding in the area. What started as a 10-meter-wide breach eventually became a breach of approximately 225 meters (738 feet) wide. This flooding of China’s second-largest freshwater lake has already affected approximately 5,000 people, and around 3,000 people were relocated on Saturday. Efforts to seal the breach in the embankment in Huarong County are underway, with over 4700 people actively helping to control the flood.

JULY 7

📈 Peak in Death Rates | On Sunday, reports of China facing an imminent peak in death rates went trending on Weibo, where a related hashtag became one of the most-searched topics (#中国将迎来人口死亡高峰#). Chinese news outlet Jiemian News reported on a new study published in the latest issue of the Chinese magazine “Population Research” (人口研究), where researchers predict an unprecedented peak in death rates due to various factors, including China’s rapidly aging population, historical birth fluctuations, and increased longevity. As the aging population from the post-war mid-20th-century birth boom leads to a rapid rise in deaths, researchers emphasize the need to prepare for the societal impacts of this peak, including improved palliative care and better planning for funeral services. “Can we first fix the problem of post-graduate unemployment?” one top commenter wondered.

What’s Noteworthy

Do you remember when US Treasury Secretary Yellen had some supposed ‘magic mushrooms’ in Beijing? The mushroom dish she had at a local restaurant is called “jiànshǒuqīng” (见手青) in Chinese; it’s the Lanmaoa asiatica mushroom species that grows in China’s Yunnan region and is considered hallucinogenic if not prepared properly, causing visions that locals call “xiǎorénrén” (小人人), literally meaning seeing “tiny people.” The Chinese is similar to the English term “Lilliputian hallucinations” that refers to visual hallucinations which could also include seeing tiny humans.

The fact that Yellen had this dish actually made it more popular online in China, leading more people to order the mushrooms through online channels.

This week, one Chinese girl named Xiaolin who had ordered 500 grams of the mushrooms became a top trending topic online. She used them for her mushroom soup and added them to her noodles. She consumed all of the mushrooms within one day. Later that night, Xiaolin started feeling unwell. She started seeing numerous “tiny people” running around her house, and when the little figures tried to whisper in her ear and get into her bed, the terrified girl rushed to her friend’s house, who decided to take her to the hospital due to her incoherent speech and strange behavior. The girl was eventually hospitalized due to wild mushroom poisoning.

The story garnered 160 million views on Weibo (#女子吃1斤见手青后看见一屋人#), where many people are now more aware of the dangers of consuming wild mushrooms if not properly cooked. However, there are also many others who are only more curious now; they also want to see ‘little people’ walking around their house.

Meme comparing Vision Pro to the ‘magic’ jianshouqing mushroom: which surreal experience is better?

Some memes relating to this topic suggest that having “jiànshǒuqīng” is a cheaper and more interactive VR experience than getting the Apple Vision Pro. It surely isn’t something that authorities would like to see more people experiment with: a vlogger who tried out some raw mushrooms on her livestream was immediately shut down this week.

What’s Popular

The highly anticipated Chinese film Wild Child (野孩子) was scheduled for a nationwide premiere on July 10. Earlier this year, Wild Child won the Weibo award for the most-anticipated movie of the year. Starring the immensely popular former TFBoys leader Wang Junkai (also known as Karry Wang 王俊凯, 1999), the film had generated significant excitement among Chinese movie-goers. However, this week, the film distributor abruptly announced the cancellation of its release, citing alleged post-production delays. The cancellation, which quickly trended and sparked widespread discussion on Chinese social media, was particularly surprising as tickets were already being sold in the presale box office.

Directed by Yin Ruoxin (殷若昕), Wild Child is based on a true story about two boys from a poor background who struggle to get by. The film addresses the theme of “children living in difficulty” (困境儿童), depicting the lives of children growing up in poverty. The two boys, one a thief and the other an orphan, are united by fate and bond as brothers as they face their challenges together.

Why was the movie canceled so close to its premiere date? Was the withdrawal a purely commercial decision driven by poor presale figures, as suggested in a recent column by People’s Daily, or were there political motivations involved? Could its theme be misaligned with the upcoming Party’s third plenary session? Or is the portrayal of children facing social difficulties simply too sensitive? While the true reasons remain unclear, many fans are hopeful they will still have the opportunity to see the film.

What’s Memorable

For this pick from the archive, and in the context of recent discussions on bystanders not intervening, we revisit a 2015 article about a young Chinese student who helped an elderly lady who had fallen on the street, only to be held liable for her injuries. Stories like these are often cited to explain why people hesitate to help someone in need.

Weibo Word of the Week

“City or not” | Our Weibo phrase of the week is City bu City a (City不City啊), translated as “City or not?”, a phrase that has recently taken the Chinese internet by storm.

The phrase first became popular thanks to American influencer Paul Mike Ashton, nicknamed “Bao Bao Xiong” (保保熊, Baby Bear), who runs a Chinese-language account on Douyin. On his channel, Ashton shares humorous snippets about his life in China, where he works as an entertainer and tour guide.

In one video from April this year, Ashton posted a clip in which he cycles through the city like a Shanghai ‘city girl’ who often mixes Chinese and English words, calling himself “very city” (“我是好city”). He says: “I’m so city, a city girl. It’s so cool, breezy. Life in the city is so good, I feel so free.”

Ashton later began incorporating this phrase more frequently in his videos, often involving his sister, who also speaks Chinese in these humorous exchanges. Walking on the Shanghai Bund, the brother and sister describe Shanghai as “so city” (“好city啊”). While walking on the Great Wall, Bao Bao asks his sister if it’s “city or not” (it’s not).

In other videos in which the two are traveling through China, Ashton repeatedly asks his younger sister if certain things are “city or not,” to which she usually responds humorously: “It’s very city.”

In this context, “city” has evolved from a noun into a quirky adjective, describing something that embodies the essence of urban life; something that is ‘city’ is metropolitan, lively, and modern. It’s very tongue-in-cheek and also serves as a playful commentary on how young Chinese people often mix Chinese and English words to sound more sophisticated and trendy.

This phenomenon sparked the ‘city or not’ meme, which even reached the Foreign Ministry this week when spokesperson Mao Ning was asked about it. She responded that she had heard about the new use of the phrase and that it is a positive sign of foreigners enjoying life in China.

Chinese authorities and state media have also jumped on this trend to promote tourism. By now, the meme has been imitated and adapted by various local tourism departments. Ashton himself has encouraged foreigners to come and experience Chinese culture (and its very ‘city’ city life), further boosting its popularity.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?