Backgrounder

This Was Trending in China in 2018: The 18 Biggest Weibo Hashtags of the Year

Published

6 years agoon

First published

PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

It’s been an eventful 2018 on Chinese social media. What’s on Weibo lists the 18 topics that have generated the most views and discussions on Chinese social media platform Sina Weibo over the past year.

What’s trending in Western media when it comes to China is not necessarily what is trending on Chinese social media, too. While topics such as the Xinjiang ‘re-education centers’, China’s nascent Social Credit System, #MeToo in China, or the allegedly “banned” Winnie the Pooh movie were some of the biggest China-related topics on social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook this year, Chinese internet users were discussing other things – some issues trending in the Western media were not as big within the PRC due to censorship, but some also simply weren’t as big because of a seeming lack of public interest.

What’s on Weibo has selected the 18 biggest hashtags that were trending on Weibo in 2018, mostly based on their total views, but also based on the impact they had on the meme machine, and the overall discussions that flooded Wechat.

This list has been fully compiled by What’s on Weibo.1 Please note that we have left some topics and hashtags out. One such example is the World Cup. While the World Cup hashtag (#世界杯#) has received a staggering 31 billion views on Weibo alone, this is a more general hashtag that has also been used before 2018; we have attempted to make a selection of topics that were the biggest of this year and 2018 alone.

Due to the scope of this article, some major topics such as the arrest of Richard Liu, the Changchun vaccine scandal, or the online success of the two vlogging farmers and their bamboo rats, did not make the cut, simply because other hashtags garnered more views.

Here we go –

#1 The Didi Murders

Hashtag “Female Passenger Murdered by Didi Driver” (#女孩乘滴滴顺风车遇害#) – 2,45 billion views on Weibo. Hashtag “Stewardess Killed in Didi Ride” #空姐滴滴打车遇害案# – 55 million views.

This year Didi Chuxing, China’s most popular car-hailing app, faced huge public backlash on Weibo, where netizens threatened to boycott the company amid safety concerns. Over the past years, Didi has seen dozens of cases where female passengers were assaulted by their drivers. The terrible murders of two young women in 2018 sparked national outrage.

In May of this year, the murder of a 21-year-old flight attendant by her Didi driver became a major topic of discussion on Weibo. The young woman, Li Mingzhu, was killed in the early morning when she was on her way home from Zhengzhou airport. The body of the driver who killed Li was later found in a nearby river. In August, the 20-year-old passenger Xiao Zhao was raped and stabbed to death by her Didi driver on her way to a birthday party on a Friday afternoon. Hours later, the driver was arrested.

What contributed to the major impact this topic had on social media was the fact that several people came forward on WeChat and Weibo to tell how Didi was warned beforehand: Xiao’s friend immediately contacted Didi after her friend had called out for help during that fatal ride, but she was told to wait and no immediate action was taken. Another female claimed she had already reported the driver to Didi for indecent behavior earlier that week.

In a rapidly changing society where companies such as Didi play an increasingly important role in how people travel and navigate their lives, the Didi murders not only showed the enormous responsibility these companies have in creating a safe environment for passengers, but also showed that the public expects these companies to provide these secure conditions.

After the August murder, Didi suspended its Hitch service, which pairs drivers and passengers traveling the same route (the young women were killed while using Hitch), and added several new safety features to make Didi safer for passengers and to quickly assist customers with any problems they might have.

#2 Flaunt Wealth Challenge

Hashtag “Flaunt Your Wealth Challenge” (#炫富挑战#) – 2,3 billion views

The ‘Flaunt Your Wealth’ or ‘Falling Stars’ hype, in which people post staged photos of themselves ‘falling’ out of their vehicles surrounded by luxury items, first spread on social media in Russia in the summer of 2018, and then made its way to other countries. In China, it became one of the biggest social media hypes of this year.

But besides those photos of seemingly rich Chinese ‘falling’ out of their super expensive cars surrounded by Gucci bags and Chanel make-up, there was also an anti-movement that became hugely popular. It showed how people were mocking the challenge by laying on the floor surrounded by their diplomas, military credential, or study books – defying superficial ideas on the meaning of ‘wealth’ and what it actually looks like.

#3 The Traveling Frog Craze

Hashtag “Traveling Frog” (#旅行青蛙#) – 2,1 billion views

1997 was the year of Tamagotchi, 2018 was the year of the Traveling Frog. The mobile game, designed by a Japanese company, took Chinese social media by storm this year, with thousands of people sharing their struggles in taking care of their virtual frog, which often goes traveling.

The game is characterized by its rather uneventful nature. While at home, the frog sits around and eats or reads, and while away, the player can’t do anything but take care of the garden and wait for their virtual friend to send them a postcard before finally returning.

There are various theories explaining the success of the game. Some say the uneventful app is appealing for young Chinese with stressful lives since it has a calming effect, others might suggest it offers a sense of ‘home’ in a society where fewer people feel at home where they live, and there were even some voices in state media ascribing the success to China’s low birth rates.

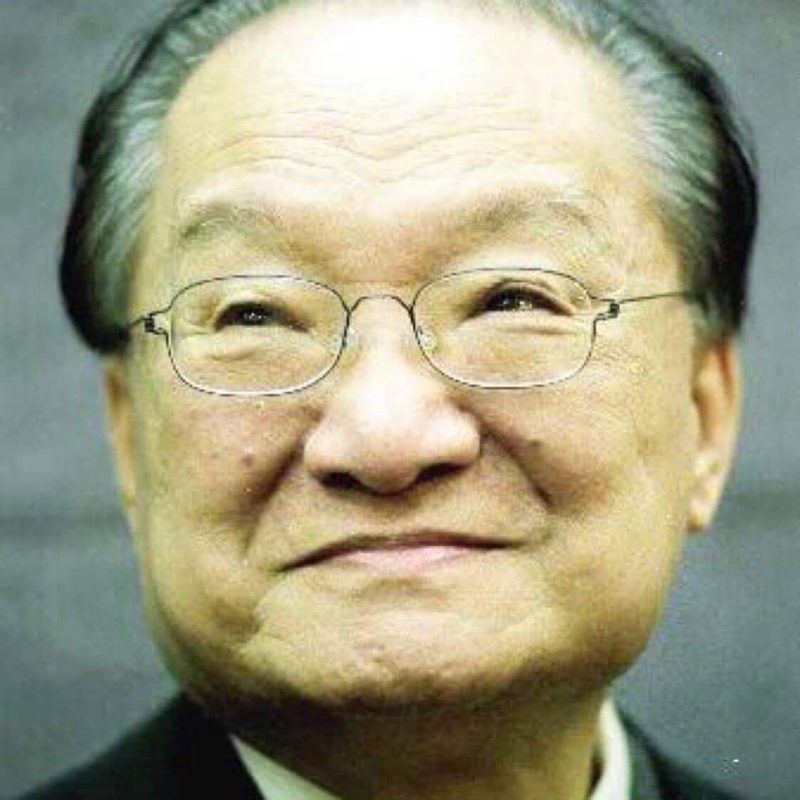

#4 Jin Yong Passes Away

Hashtag “Jin Yong Passes Away” (#金庸去世#) – 2 billion views on Weibo

The passing of Chinese wuxia novelist Jin Yong (查良鏞), also known as Louis Cha, became big news on Chinese social media this fall. Wuxia (武俠) is a genre of Chinese fiction that focuses on the adventures of martial artists in ancient China, and Jin Yong is regarded as one of the best – if not the top – authors within the genre. Many of his works, of which over 300 million copies were sold worldwide, have been turned into tv series and films.

Jin’s passing set off waves of nostalgia on Weibo, where thousands of netizens shared their favorite works and scenes, thanked the author for all he did, and praised his contributions to Chinese popular culture.

Another person who passed away in November of 2018 is the renowned Hong Kong actress Yammie Lam (藍潔瑛). News of her death also received millions of views on Chinese social media.

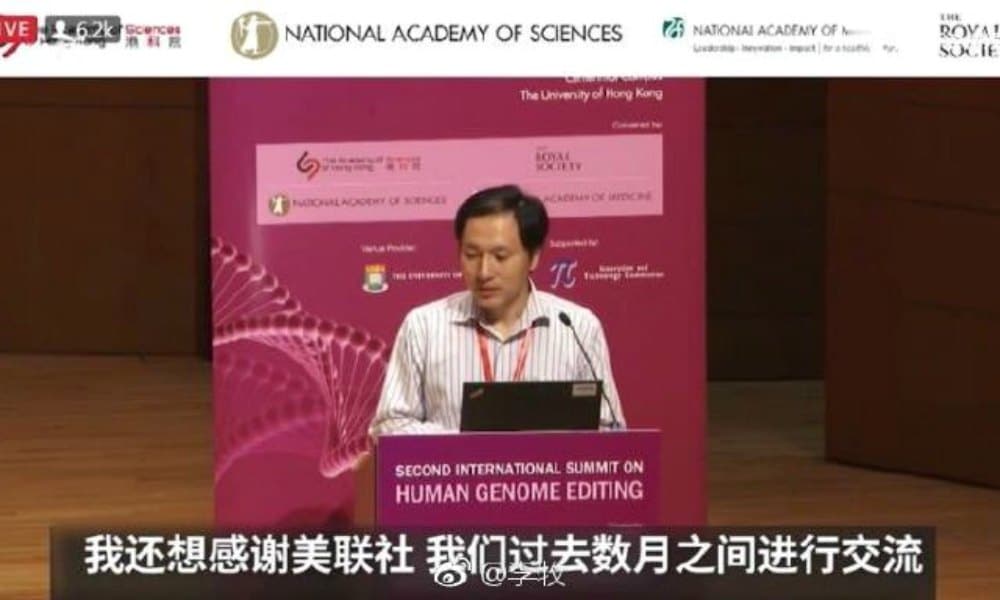

#5 Gene-modified Babies

Hashtag “First Case of Gene-Edited HIV Immune Babies” (#首例免疫艾滋病基因编辑婴儿#) – 1,9 billion Weibo views

News that a Chinese researcher from Shenzen has helped make the world’s first genetically edited babies made international headlines in November of this year. He Jiankui (贺建奎) claimed that together with his research team, he succeeded in altering the DNA of embryos, making them resistant to HIV. The twin girls were born earlier this year.

On social media, the topic received many mixed reactions, with many condemning the researcher’s work, and others praising it. Chinese authorities launched an investigation into the research shortly after news came out, and He Jiankui has not been heard of since. Many people on Weibo are now wondering about his whereabouts, what will happen to him, and how this will further impact the lives of the two girls whose genes were edited.

#6 Golden Horse Ceremony’s ‘Taiwan’ Speech

Hashtag “Gong Li Refuses to Confer Award” (#巩俐拒绝颁奖#) – 1,9 billion views on Weibo

The annual Golden Horse Film Awards in Taipei turned out to be a painful confrontation between mainland actors and Taiwanese pro-independence supporters this year. Although Ang Lee, chairman of the Golden Horse committee, had probably hoped to keep politics out of the film festival, the atmosphere of the live-streamed event changed when award-winning director Fu Yue expressed her hopes for an independent Taiwan during her acceptance speech. Later on in the show, actor Tu Men from mainland China struck back on stage by saying he was honored to present an award in “China, Taiwan.”

Things got more polarized and political when famous Chinese actress Gong Li, at the end of the show, refused to get on stage with Ang Lee to present the award for Best Feature Film. The evening officially seemed ruined when, at the end of the night, it turned out that most mainland actors and producers declined taking part in the celebratory award dinner and went straight back to the mainland instead.

This was not the only topic this year that showed that the current and future status of Taiwan is still an incredibly sensitive topic that can set off waves of angry nationalism on social media. A brief visit to Taiwanese bakery 85°C by ROC President Tsai Ing-wen and the surfacing of an old video of actress Vivian Sung in which she called Taiwan her “favorite country” also triggered major discussions on cross-Straits relations.

#7 Chongqing Bus Plunges Into River

Hashtag “Why Chongqing Bus Plunged in the River” (#重庆公交车坠江原因#) – 1,4 billion Weibo views

In late October of this year, an incident in which a public bus plunged off a bridge into the Yangtze river, causing all 15 passengers to die, became a huge topic on Chinese social media. The security camera footage from inside the bus later showed how a passenger who apparently had missed her stop gets angry with the driver and starts hitting him with her mobile phone. The driver then abruptly turns the steering wheel, hitting oncoming traffic, crashes through the safety fence, and plunges into the river.

The incident caused major concerns over aggression in Chinese public transport, with other videos of similar incidents also making their rounds on social media. The city of Nanjing soon introduced security partitions on buses, and the existence of special “grievance awards” for bus drivers who do not respond to angry passengers also became a topic of debate. Many people on Weibo called for bus cards to be linked to one’s identity so that troublemakers will be able to be blacklisted from buses in the future.

#8 The Kunshan Stabbing Case

Hashtag (#追砍电动车主遭反杀#) – 1,25 billion views on Weibo

A bizarre road-rage incident in which a muscular and tattooed BMW driver attacked an innocent cyclist with a big knife, but then ended up dead himself, was the biggest story on Chinese social media this summer, triggering countless of memes.

The entire scene was caught on security cameras. In the night of August 27, a BMW switched from the car lane to the bicycle lane in the city of Kunshan (Jiangsu), colliding with a man driving his bike, who seemingly refused to give way. Two men then step out of their BMW vehicle to confront the cyclist, with one man going back to his vehicle, suddenly pulling out a long knife and going after the cyclist, stabbing him. During the fight, however, the BMW driver suddenly lets the knife slip out of his hands, after which the bike owner quickly picks it up. With the knife in his hands, he now starts attacking the BMW driver, who eventually dies of his injuries.

One of the main reasons for the mass focus on this incident was that there was an ethical question involved, namely: to what extent could this be regarded as legitimate self-defense? It did not take long for the answer to come out, as authorities ruled it self-defense in September. For many, the news was proof that justice had prevailed.

#9 The Dolce and Gabbana Controversy

Hashtag “D&G Show Canceled” #DG大秀取消# and “D&G Designer Responds Again” (#dg设计师再次回应#) – 820 & 940 million views on Weibo

Although 2018 was supposed to be a great China year for Italian luxury brand Dolce & Gabbana, things unexpectedly spiraled out of control in November of this year, while the brand’s “D&G Loves China” campaign was in full swing.

It started with criticism on a video that was launched by the fashion brand to promote its upcoming Shanghai show. The video, that shows a Chinese model failing to eat Italian food with her chopsticks, was deemed sexist and insulting by many. Things started going downhill real fast after screenshots of comments attributed to fashion designer Stefano Gabbana, in which he scolds China and makes derogatory remarks about Chinese, went viral. It soon led to the cancellation of the big D&G show in Shanghai.

Despite apologies issued by the D&G founders, many netizens called for a boycott of the brand. It is yet unclear to what extent the marketing disaster has affected the brand, but one thing this incident shows is that cultural insensitivities in marketing campaigns can soon lead to a public relations mess.

#10 Wang Baoqiang’s Divorce Drama Continues

Hashtag “Wang Baoqiang Beats up Ma Rong” #王宝强殴打马蓉#) received some 520 million views before it was taken offline

Will there be another year when the 2016 split between Chinese celebrities Wang Baoqiang (王宝强) and ex-wife Ma Rong (马蓉) does not make into the top-trending lists?! Ever since the dramatic divorce of the two became one of the top hashtags of 2016, their fights have continued to be a major topic on Chinese social media.

This time, Chinese actress Ma Rong claimed that her ex-husband attacked her when she came to pick up her children at his house in early December. Dramatic photos and hospital footage soon made their rounds on Weibo, but when news came out that the ‘attack’ might have been staged, and that Ma Rong had caused a scene at her ex’s house, netizens condemned the actress for her actions.

The incident became a major source of inspiration for the Weibo meme machine, where others imitated the dramatic Ma Rong photo and photo-shopped it into gossip magazines.

#11 The High-Speed Train Tyrants

Hashtag “High-speed Train Tyrant Woman” (#高铁霸座女#) – 505 million views and #高铁霸座事件# – 110 million views

The two train tyrants of 2018 will probably go down in China’s social media history for their meme-worthy and bizarre behavior, that triggered a storm of criticism online. Both of their bad behaviors on high-speed trains were caught on video.

In August of this year, one rude man from Shandong, who refused to give up the seat he took from another passenger, became known as the “High-Speed Train Tyrant” (高铁霸座男 gāotiě bà zuò nán) on Chinese social media. A video showing the man’s rude behavior went viral, and netizens were especially angry because the man pretended he could not get up from the stolen seat and needed a wheelchair – although he did not need one when boarding the train.

In September of 2018, a woman from Hunan, who was dubbed ‘High-Speed Train Tyrant Woman’ (高铁霸座女 gāotiě bà zuò nǚ) by Weibo netizens, had also taken a seat assigned to another passenger while riding the train from Yongzhou to Shenzhen. Despite the conductor’s reasoning, she refused to get up from her window seat to return to her own seat.

Netizens soon linked the two ‘Train Tyrants,’ creating dozens of memes that showed the two as lovebirds getting married. The incidents also showed public support of China’s nascent Social Credit System, with many calling for a system that would allow these kinds of misbehaving people to be blacklisted from public transport in general.

#12 Invictus Gaming: The E-Sports Craze in China

Hashtag “The Meaning of IG Championship” #IG夺冠的意义# – 540 million views on Weibo

People were going absolutely crazy over the success of China’s e-sports when ‘Invictus Gaming’ (IG) became the first Chinese team to win the League of Legends World Championship. Students were hanging banners from their dorm rooms, videos of cheering crowds in school canteens flooded Weibo, and dozens of new memes surfaced on Chinese social media. One of them showed two monkeys with a big “Congratulations IG” above them and one wondering “What is IG?!”, and the other telling him just to follow the rest in congratulating them anyway, signaling that many people had never heard of ‘Invictus Gaming’ before, and were clueless about the top trending lists being filled up with this new topic.

China’s e-sports craze also made one Weibo post the most popular of all time, when billionaire Wang Sicong announced he would be giving away more than $160,000 to Weibo users to celebrate the victory of the Chinese team.

#13 The Boy who was Duped at the Hair Salon

Hashtag “Hairline-boy expressions” (#发际线男孩表情包#) – viewed 470 million times on Weibo

What was supposed to be a quick visit to the hairdresser turned into a disaster when the 18-year-old Wu Zhengqiang (吴正强) was presented with a 40,000 yuan ($5750) bill and a bad haircut. Although the teenager eventually could pay a much lower amount of money to the salon, Wu turned to local media to tell about his unfortunate haircut, and shared that he was not just sad about losing the money, but that he was also unhappy with his new hairstyle and hairline.

The story soon went viral and triggered the creation of dozens of new memes across Chinese social media, turning the duped boy into one of the biggest internet sensations of 2018.

#14 Meng Wanzhou WeChat Moments Post

Hashtag “Meng Wanzhou’s WeChat Moments Post after Release” (#孟晚舟保释后发朋友圈#) – 380 million views on Weibo

The December 1st arrest of Meng Wanzhou (孟晚舟), the financial officer of Chinese telecom giant Huawei Technology – which happens to have been founded by her father, Ren Zhengfei (任正非), – became huge news in China and across the world.

Meng was detained during a transit at the Vancouver airport at the request of United States officials. She is accused of fraud for violating US sanctions on Iran. Meng allegedly helped Huawei get around these sanctions by misleading financial institutions into believing that subsidiary company ‘Skycom’ was a separate company in order to conduct business in Iran. Chinese officials, demanding Meng’s release, have called the arrest “a violation of a person’s human rights.”

Meng was released on bail on December 11th. She then shared an update on her Wechat ‘Moments’ page, which received mass attention on Weibo. It showed the feet of a ballet dancer along with a quote saying that “there is suffering behind greatness” (伟大的背后都是苦难). Meng also thanked people for their support, and in doing so, once again received thousands of supportive messages on social media.

#15 The Tang Lanlan Case

Hashtag “The Truth about the Tang LanLan Case” (#汤兰兰案真相调查#) – viewed 340 million times on Weibo (also 汤兰兰性侵案 => hashtag now removed, then 50 million views)

The news story of a decade-old abuse case caused an uproar on Chinese social media in late January of 2018, when many netizens on Weibo believed that reporters of the story were biased and were harming the privacy of Tang Lanlan, the alleged victim in the case.

In 2008, a then 14-year-old girl named Tang Lanlan (汤兰兰, pseudonym) accused her father, grandfather, uncles, teachers, the rural director and neighbors of sexually abusing her since the age of seven. It later led to the prosecution of 11 people for rape and forced prostitution of a minor – including Tang’s own parents. As some of those people, including Tang’s mother, had since been released after serving their sentence, they sought the attention of the media in claiming that Tang, now 23 years old, had fabricated the story and that they were searching for her.

Netizens harshly criticized Chinese media outlets such as The Paper for featuring the story and giving away details about the identity of Tang, saying they should protect the victim instead of choosing the side of those convicted. The outrage was so huge that some reporters were even doxxed by netizens, and that articles and hashtags were removed, making the Tang Lan Lang case the greatest clash between Chinese media and netizens in 2018.

#16 Foreigners’ “Preferential Treatment”

Hashtag “Pretend to be foreign and Ofo gives back deposit right away” (#假装外国人ofo秒退押金#) – 250 million views.

There have been many topics over the past year that involved national pride and Chinese social media users feeling insulted or discriminated against. One such topic is the recent collective anger directed at bike sharing platform Ofo for allegedly helping foreigners much quicker than Chinese nationals.

A Weibo user who did not feel like waiting for hours on the phone to get his Ofo deposit back decided to pose as a foreigner to see if it would help. He sent an email in English via Gmail to Ofo, requesting his deposit back. It worked. He posted about it on Weibo, and millions of people responded with anger. Earlier in 2018, there was also outrage when a short movie went viral on Chinese social media that exposed the big differences between the dorm conditions of Chinese students and of foreigners studying in China.

#17 The Sweden Controversy

Hashtag “Chinese Tourists Abused by Swedish Police” #中国游客遭瑞典警察粗暴对待# and “Swedish TV Show Insults China” #瑞典辱华节目#– 170 and 50 million views on Weibo

See article here and here

The alleged maltreatment of a Chinese family in Stockholm ignited major discussions on Chinese social media this September when footage showed how a Chinese man was dragged out of a hotel lobby by Swedish police, while his elderly parents were crying on the sidewalk. The dramatic footage was shot after the tourists arrived at their hotel long before check-in time, and were refused permission to stay overnight in the lobby. When they refused to leave, police got involved.

Chinese media greatly criticized Swedish authorities for how they handled the incident, and it even led to the Chinese embassy in Sweden issuing a safety alert. Not long after, a satirical Swedish TV show made fun of Chinese people through a sketch that listed a number of do’s and don’ts for Chinese tourists, including “not taking a poo outside of historical places.” The TV show added fuel to the fire and was condemned by Chinese social media users. The Chinese embassy in Sweden denounced the satirical Swedish TV show for “maliciously attacking” China. The entire ordeal did not do any good for the relations between Sweden and China, that have already been tense due to the imprisonment of Swedish-Chinese author Gui Minhai.

#18 Fugitives on the Loose

Hashtag “Two Fugitives on the Loose” (#两名重刑犯逃脱#) – 170 million views

It was almost like a movie: two criminals spectacularly escaped from a Liaoning prison and the entire country went on a manhunt, with authorities giving out a big reward for those who’d catch them and setting out drones to catch the two.

Social media played an important role in the search for the fugitives, that took place in early October of this year. Ten thousands of people closely followed the ordeal, as security footage from a local store was posted online only hours after their escape, showing the two criminals buying some food and cigarettes. Within 50 hours of their escape, the fugitives were captured by the police through the help of local villagers.

While you’re here, also check out the top 30 best books to understand China we published earlier this year!

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

*1 (We kindly ask not to reproduce this list without permission – please link back if referring to it).

Directly support Manya Koetse. By supporting this author you make future articles possible and help the maintenance and independence of this site. Donate directly through Paypal here. Also check out the What’s on Weibo donations page for donations through creditcard & WeChat and for more information.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

Backgrounder

“Oppenheimer” in China: Highlighting the Story of Qian Xuesen

Qian Xuesen is a renowned Chinese scientist whose life shares remarkable parallels with Oppenheimer’s.

Published

10 months agoon

September 16, 2023By

Zilan Qian

They shared the same campus, lived in the same era, and both played pivotal roles in shaping modern history while navigating the intricate interplay between science and politics. With the release of the “Oppenheimer” movie in China, the renowned Chinese scientist Qian Xuesen is being compared to the American J. Robert Oppenheimer.

In late August, the highly anticipated U.S. movie Oppenheimer finally premiered in China, shedding light on the life of the famous American theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904-1967).

Besides igniting discussions about the life of this prominent scientist, the film has also reignited domestic media and public interest in Chinese scientists connected to Oppenheimer and nuclear physics.

There is one Chinese scientist whose life shares remarkable parallels with Oppenheimer’s. This is aerospace engineer and cyberneticist Qian Xuesen (钱学森, 1911-2009). Like Oppenheimer, he pursued his postgraduate studies overseas, taught at Caltech, and played a pivotal role during World War II for the US.

Qian Xuesen is so widely recognized in China that whenever I introduce myself there, I often clarify my last name by saying, “it’s the same Qian as Qian Xuesen’s,” to ensure that people get my name.

Some Chinese blogs recently compared the academic paths and scholarly contributions of the two scientists, while others highlighted the similarities in their political challenges, including the revocation of their security clearances.

The era of McCarthyism in the United States cast a shadow over Qian’s career, and, similar to Oppenheimer, he was branded as a “communist suspect.” Eventually, these political pressures forced him to return to China.

Although Qian’s return to China made his later life different from Oppenheimer’s, both scientists lived their lives navigating the complex dynamics between science and politics. Here, we provide a brief overview of the life and accomplishments of Qian Xuesen.

Departing: Going to America

Qian Xuesen (钱学森, also written as Hsue-Shen Tsien), often referred to as the “father of China’s missile and space program,” was born in Shanghai in 1911,1 a pivotal year marked by a historic revolution that brought an end to the imperial dynasty and gave rise to the Republic of China.

Much like Oppenheimer, who pursued further studies at Cambridge after completing his undergraduate education, Qian embarked on a journey to the United States following his bachelor’s studies at National Chiao Tung University (now Shanghai Jiao Tong University). He spent a year at Tsinghua University in preparation for his departure.

The year was 1935, during the eighth year of the Chinese Civil War and the fourth year of Japan’s invasion of China, setting the backdrop for his academic pursuits in a turbulent era.

Qian in his office at Caltech (image source).

One year after arriving in the U.S., Qian earned his master’s degree in aeronautical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Three years later, in 1939, the 27-year-old Qian Xuesen completed his PhD at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), the very institution where Oppenheimer had been welcomed in 1927. In 1943, Qian solidified his position in academia as an associate professor at Caltech. While at Caltech, Qian helped found NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

When World War II began, while Oppenheimer was overseeing the Manhattan Project’s efforts to assist the U.S. in developing the atomic bomb, Qian actively supported the U.S. government. He served on the U.S. government’s Scientific Advisory Board and attained the rank of lieutenant colonel.

The first meeting of the US Department of the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board in 1946. The predecessor, the Scientific Advisory Group, was founded in 1944 to evaluate the aeronautical programs and facilities of the Axis powers of World War II. Qian can be seen standing in the back, the second on the left (image source).

After the war, Qian went to teach at MIT and returned to Caltech as a full-time professor in 1949. During that same year, Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Just one year later, the newly-formed nation became involved in the Korean War, and China fought a bloody battle against the United States.

Red Scare: Being Labeled as a Communist

Robert Oppenheimer and Qian Xuesen both had an interest in Communism even prior to World War II, attending communist gatherings and showing sympathy towards the Communist cause.

Qian and Oppenheimer may have briefly met each other through their shared involvement in communist activities. During his time at Caltech, Qian secretly attended meetings with Frank Oppenheimer, the brother of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Monk 2013).

However, it was only after the war that their political leanings became a focal point for the FBI.

Just as the FBI accused Oppenheimer of being an agent of the Soviet Union, they quickly labeled Qian as a subversive communist, largely due to his Chinese heritage. While the government did not succeed in proving that Qian had communist ties with China during that period, they did ultimately succeed in portraying Qian as a communist affiliated with China a decade later.

During the transition from the 1940s to the 1950s, the Cold War was underway, and the anti-communist witch-hunts associated with the McCarthy era started to intensify (BBC 2020).

In 1950, the Korean War erupted, with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) joining North Korea in the conflict against South Korea, which received support from the United States. It was during this tumultuous period that the FBI officially accused Qian of communist sympathies in 1950, leading to the revocation of his security clearance despite objections from Qian’s colleagues. Four years later, in 1954, Robert Oppenheimer went through a similar process.

The 1950’s security hearing of Qian (second left). (Image source).

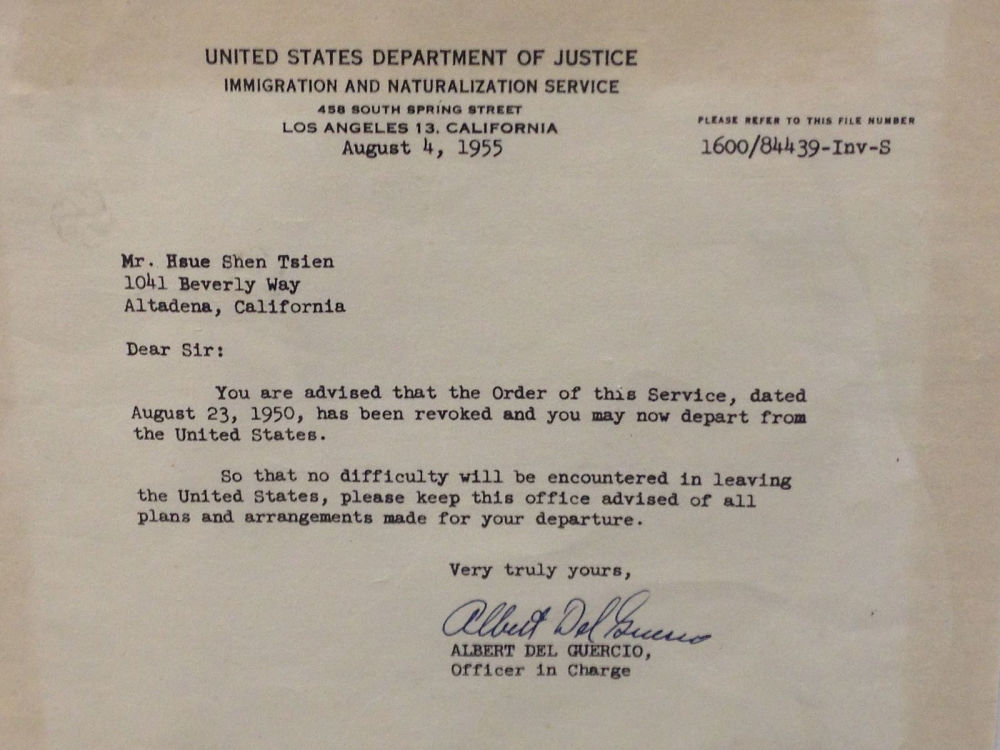

After losing his security clearance, Qian began to pack up, saying he wanted to visit his aging parents back home. Federal agents seized his luggage, which they claimed contained classified materials, and arrested him on suspicion of subversive activity. Although Qian denied any Communist leanings and rejected the accusation, he was detained by the government in California and spent the next five years under house arrest.

Five years later, in 1955, two years after the end of the Korean War, Qian was sent home to China as part of an apparent exchange for 11 American airmen who had been captured during the war. He told waiting reporters he “would never step foot in America again,” and he kept his promise (BBC 2020).

A letter from the US Immigration and Naturalization Service to Qian Xuesen, dated August 4, 1955, in which he was notified he was allowed to leave the US. The original copy is owned by Qian Xuesen Library of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, where the photo was taken. (Caption and image via wiki).

Dan Kimball, who was the Secretary of the US Navy at the time, expressed his regret about Qian’s departure, reportedly stating, “I’d rather shoot him dead than let him leave America. Wherever he goes, he equals five divisions.” He also stated: “It was the stupidest thing this country ever did. He was no more a communist than I was, and we forced him to go” (Perrett & Bradley, 2008).

Kimball may have foreseen the unfolding events accurately. After his return to China, Qian did indeed assume a pivotal role in enhancing China’s military capabilities, possibly surpassing the potency of five divisions. The missile programme that Qian helped develop in China resulted in weapons which were then fired back on America, including during the 1991 Gulf War (BBC 2020).

Returning: Becoming a National Hero

The China that Qian Xuesen had left behind was an entirely different China than the one he returned to. China, although having relatively few experts in the field, was embracing new possibilities and technologies related to rocketry and space exploration.

Within less than a month of his arrival, Qian was welcomed by the then Vice Prime Minister Chen Yi, and just four months later, he had the honor of meeting Chairman Mao himself.

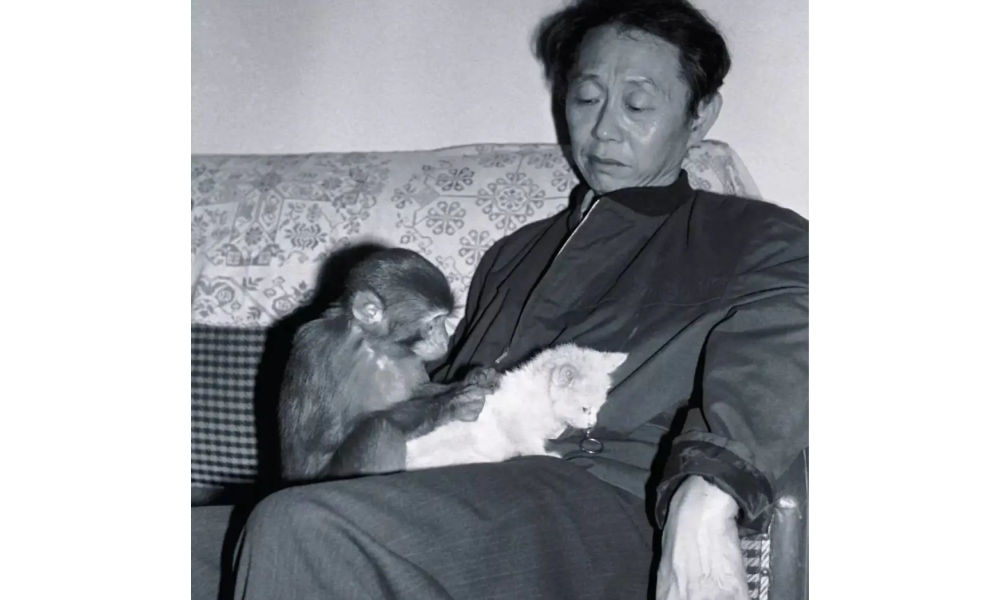

Qian and Mao (image source).

In China, Qian began a remarkably successful career in rocket science, with great support from the state. He not only assumed leadership but also earned the distinguished title of the “father” of the Chinese missile program, instrumental in equipping China with Dongfeng ballistic missiles, Silkworm anti-ship missiles, and Long March space rockets.

Additionally, his efforts laid the foundation for China’s contemporary surveillance system.

By now, Qian has become somewhat of a folk hero. His tale of returning to China despite being thwarted by the U.S. government has become like a legendary narrative in China: driven by unwavering patriotism, he willingly abandoned his overseas success, surmounted formidable challenges, and dedicated himself to his motherland.

Throughout his lifetime, Qian received numerous state medals in recognition of his work, establishing him as a nationally celebrated intellectual. From 1989 to 2001, the state-launched public movement “Learn from Qian Xuesen” was promoted throughout the country, and by 2001, when Qian turned 90, the national praise for him was on a similar level as that for Deng Xiaoping in the decade prior (Wang 2011).

Qian Xuesen remains a celebrated figure. On September 3rd of this year, a new “Qian Xuesen School” was established in Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, becoming the sixth high school bearing the scientist’s name since the founding of the first one only a year ago.

In 2017, the play “Qian Xuesen” was performed at Qian’s alma mater, Shanghai Jiaotong University. (Image source.)

Qian Xuesen’s legacy extends well beyond educational institutions. His name frequently appears in the media, including online articles, books, and other publications. There is the Qian Xuesen Library and a museum in Shanghai, containing over 70,000 artefacts related to him. Qian’s life story has also been the inspiration for a theater production and a 2012 movie titled Hsue-Shen Tsien (钱学森).2

Unanswered Questions

As is often the case when people are turned into heroes, some part of the stories are left behind while others are highlighted. This holds true for both Robert Oppenheimer and Qian Xuesen.

The Communist Party of China hailed Qian as a folk hero, aligning with their vision of a strong, patriotic nation. Many Chinese narratives avoid the debate over whether Qian’s return was linked to problems and accusations in the U.S., rather than genuine loyalty to his homeland.

In contrast, some international media have depicted Qian as a “political opportunist” who returned to China due to disillusionment with the U.S., also highlighting his criticism of “revisionist” colleagues during the Cultural Revolution and his denunciation of the 1989 student demonstrations.

Unlike the image of a resolute loyalist favored by the Chinese public, Qian’s political ideology was, in fact, not consistently aligned, and there were instances where he may have prioritized opportunity over loyalty at different stages of his life.

Qian also did not necessarily aspire to be a “flawless hero.” Upon returning to China, he declined all offers to have his biography written for him and refrained from sharing personal information with the media. Consequently, very little is known about his personal life, leaving many questions about the motivations driving him, and his true political inclinations.

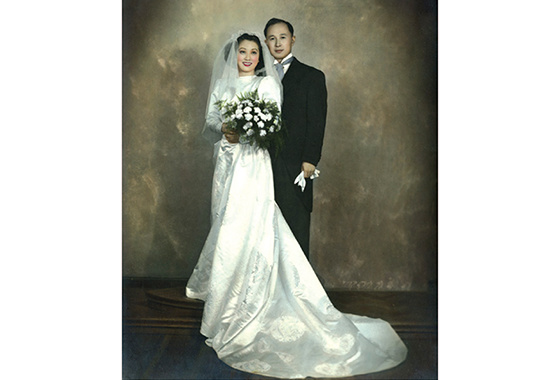

The marriage photo of Qian and Jiang. (Image source).

We do know that Qian’s wife, Jiang Ying (蒋英), had a remarkable background. She was of Chinese-Japanese mixed race and was the daughter of a prominent military strategist associated with Chiang Kai-shek. Jiang Ying was also an accomplished opera singer and later became a professor of music and opera at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing.

Just as with Qian, there remain numerous unanswered questions surrounding Oppenheimer, including the extent of his communist sympathies and whether these sympathies indirectly assisted the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Perhaps both scientists never imagined they would face these questions when they first decided to study physics. After all, they were scientists, not the heroes that some narratives portray them to be.

Also read:

■ Farewell to a Self-Taught Master: Remembering China’s Colorful, Bold, and Iconic Artist Huang Yongyu

■ “His Name Was Mao Anying”: Renewed Remembrance of Mao Zedong’s Son on Chinese Social Media

By Zilan Qian

Follow @whatsonweibo

1 Some sources claim that Qian was born in Hangzhou, while others say he was born in Shanghai with ancestral roots in Hangzhou.

2The Chinese character 钱 is typically romanized as “Qian” in Pinyin. However, “Tsien” is a romanization in Wu Chinese, which corresponds to the dialect spoken in the region where Qian Xuesen and his family have ancestral roots.

This article has been edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

References (other sources hyperlinked in text)

BBC. 2020. “Qian Xuesen: The man the US deported – who then helped China into space.” BBC.com, 27 October https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-54695598 [9.16.23].

Monk, Ray. 2013. Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center, First American Edition. New York: Doubleday.

Perrett, Bradley, and James R. Asker. 2008. “Person of the Year: Qian Xuesen.” Aviation Week and Space Technology 168 (1): 57-61.

Wang, Ning. 2011. “The Making of an Intellectual Hero: Chinese Narratives of Qian Xuesen.” The China Quarterly, 206, 352-371. doi:10.1017/S0305741011000300

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Backgrounder

Farewell to a Self-Taught Master: Remembering China’s Colorful, Bold, and Iconic Artist Huang Yongyu

Renowned Chinese artist and the creator of the ‘Blue Rabbit’ zodiac stamp Huang Yongyu has passed away at the age of 98. “I’m not afraid to die. If I’m dead, you may tickle me and see if I smile.”

Published

1 year agoon

June 15, 2023

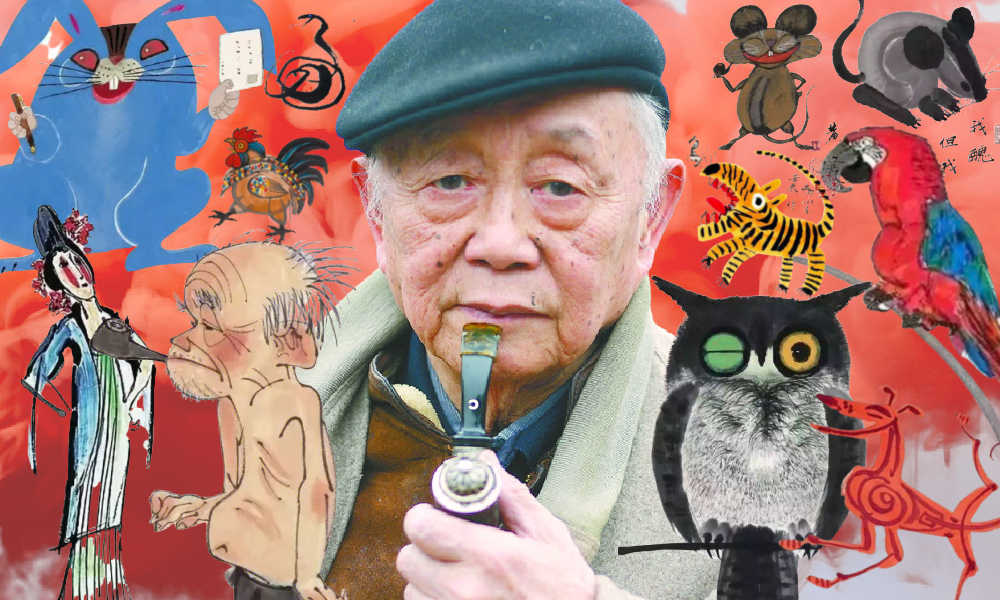

The famous Chinese painter, satirical poet, and cartoonist Huang Yongyu has passed away. Born in 1924, Huang endured war and hardship, yet never lost his zest for life. When his creativity was hindered and his work was suppressed during politically tumultuous times, he remained resilient and increased “the fun of living” by making his world more colorful.

He was a youthful optimist at old age, and will now be remembered as an immortal legend. The renowned Chinese painter and stamp designer Huang Yongyu (黄永玉) passed away on June 13 at the age of 98. His departure garnered significant attention on Chinese social media platforms this week.

On Weibo, the hashtag “Huang Yongyu Passed Away” (#黄永玉逝世#) received over 160 million views by Wednesday evening.

Huang was a member of the China National Academy of Painting (中国国家画院) as well as a Professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (中央美术学院).

Huang Yongyu is widely recognized in China for his notable contribution to stamp design, particularly for his iconic creation of the monkey stamp in 1980. Although he designed a second monkey stamp in 2016, the 1980 stamp holds significant historical importance as it marked the commencement of China Post’s annual tradition of releasing zodiac stamps, which have since become highly regarded and collectible items.

Huang’s famous money stamp that was issued by China Post in 1980.

The monkey stamp designed by Huang Yongyu has become a cherished collector’s item, even outside of China. On online marketplaces like eBay, individual stamps from this series are being sold for approximately $2000 these days.

Huang Yongyu’s latest most famous stamp was this year’s China Post zodiac stamp. The stamp, a blue rabbit with red eyes, caused some online commotion as many people thought it looked “horrific.”

Some thought the red-eyed blue rabbit looked like a rat. Others thought it looked “evil” or “monster-like.” There were also those who wondered if the blue rabbit looked so wild because it just caught Covid.

Huang’s (in)famous blue rabbit stamp.

Nevertheless, many people lined up at post offices for the stamps and they immediately sold out.

In light of the controversy, Huang Yongyu spoke about the stamps in a livestream in January of 2023. The 98-year-old artist claimed he had simply drawn the rabbit to spread joy and celebrate the new year, stating, “Painting a rabbit stamp is a happy thing. Everyone could draw my rabbit. It’s not like I’m the only one who can draw this.”

Huang’s response also went viral, with one Weibo hashtag dedicated to the topic receiving over 12 million views (#蓝兔邮票设计者直播回应争议#) at the time. Those defending Huang emphasized how it was precisely his playful, light, and unique approach to art that has made Huang’s work so famous.

A Self-Made Artist

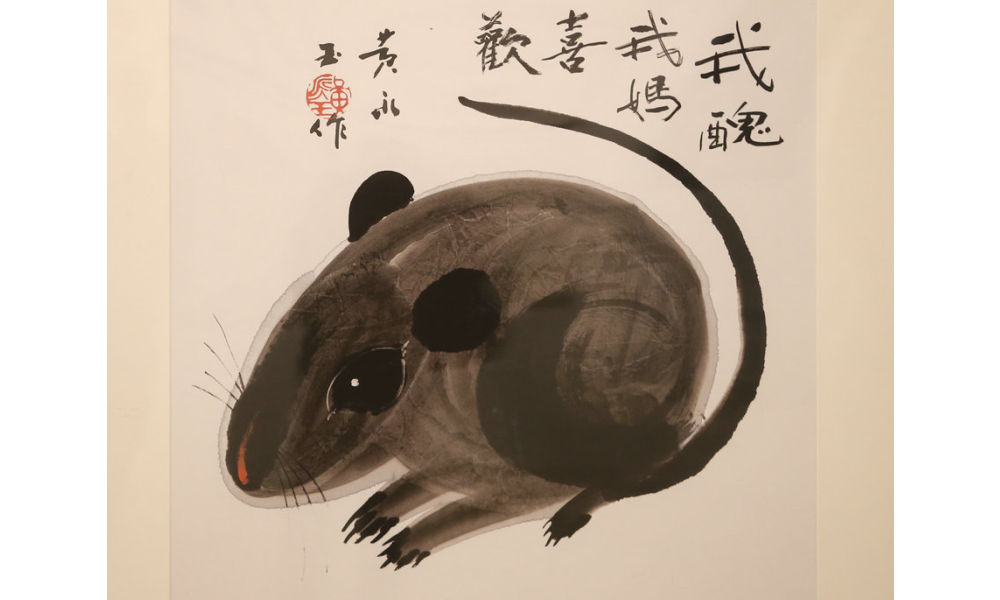

“I’m ugly, but my mum likes me”

‘Ugly Mouse’ by Huang Yongyu [Image via China Daily].

Huang Yongyu was born on August 9, 1924, in Hunan’s Chengde as a native of the Tujia ethnic group.

He was born into an extraordinary family. His grandfather, Huang Jingming (黄镜铭), worked for Xiong Xiling (熊希齡), who would become the Premier of the Republic of China. His first cousin and lifelong friend was the famous Chinese novelist Shen Congwen (沈从文). Huang’s father studied music and art and was good at drawing and playing the accordion. His mother graduated from the Second Provincial Normal School and was the first woman in her county to cut her hair short and wear a short skirt (CCTV).

Born in times of unrest and poverty, Huang never went to college and was sent away to live with relatives at the age of 13. His father would die shortly after, depriving him of a final goodbye. Huang started working in various places and regions, from porcelain workshops in Dehua to artisans’ spaces in Quanzhou. At the age of 16, Huang was already earning a living as a painter and woodcutter, showcasing his talents and setting the foundation for his future artistic pursuits.

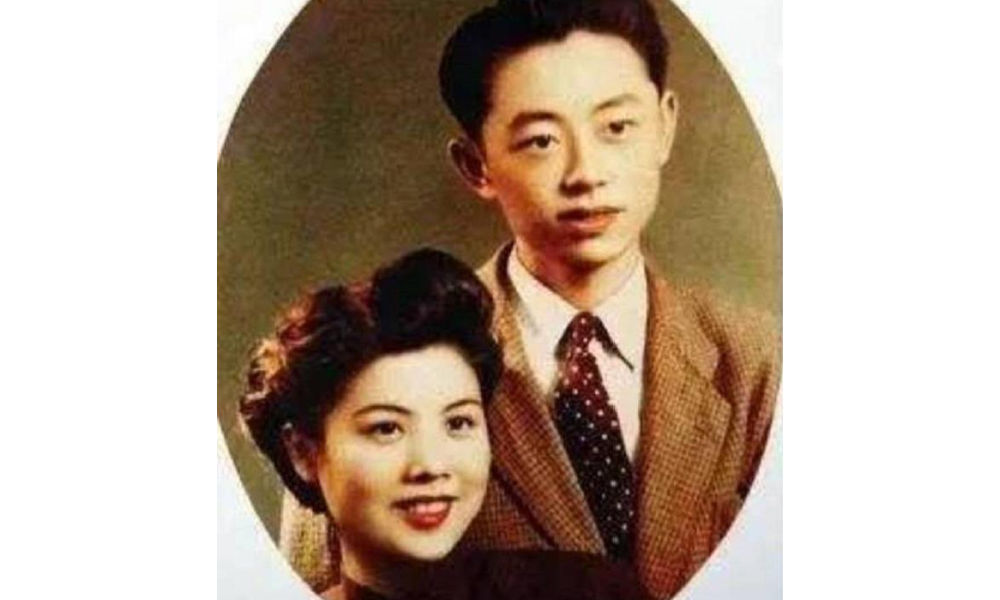

When he was 22, Huang married his first girlfriend Zhang Meixi (张梅溪), a general’s daughter, with whom he shared a love for animals. He confessed his love for her when they both found themselves in a bomb shelter after an air-raid alarm.

Huang and Zhang Meixi [163.com]

In his twenties, Huang Yongyu emerged as a sought-after artist in Hong Kong, where he had relocated in 1948 to evade persecution for his left-wing activities. Despite achieving success there, he heeded Shen Congwen’s advice in 1953 and moved to Beijing. Accompanied by his wife and their 7-month-old child, Huang took on a teaching position at the esteemed Central Academy of Fine Arts (中央美术学院).

The couple raised all kinds of animals at their Beijing home, from dogs and owls to turkeys and sika deers, and even monkeys and bears (Baike).

Throughout Huang’s career, animals played a significant role, not only reflecting his youthful spirit but also serving as vehicles for conveying satirical messages.

One recurring motif in his artwork was the incorporation of mice. In one of his famous works, a grey mouse is accompanied by the phrase ‘I’m ugly, but my mum likes me’ (‘我丑,但我妈喜欢’), reinforcing the notion that regardless of our outward appearance or circumstances, we remain beloved children in the eyes of our mothers.

As a teacher, Huang liked to keep his lessons open-minded and he, who refused to join the Party himself, stressed the importance of art over politics. He would hold “no shirt parties” in which his all-male studio students would paint in an atmosphere of openness and camaraderie during hot summer nights (Andrews 1994, 221; Hawks 2017, 99).

By 1962, creativity in the classroom was limited and there were far more restrictions to what could and could not be created, said, and taught.

Bright Colors in Dark Times

“Strengthen my resolve and increase the fun of living”

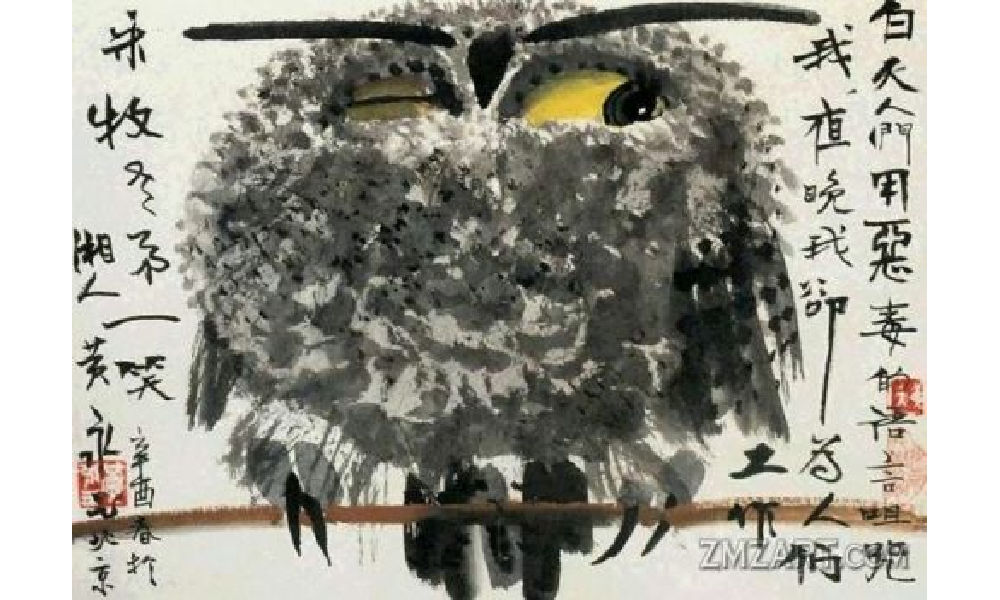

Huang Yongyu’s winking owl, 1973, via Wikiart.

In 1963, Huang was sent to the countryside as part of the “Four Cleanups” movement (四清运动, 1963-1966). Although Huang cooperated with the requirement to attend political meetings and do farm work, he distanced himself from attempts to reform his thinking. In his own time, and even during political meetings, he would continue to compose satirical and humorous pictures and captions centered around animals, which would later turn into his ‘A Can of Worms’ series (Hawks 2017, 99; see Morningsun.org).

Three years later, at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, many Chinese major artists, including Huang, were detained in makeshift jails called ‘niupeng‘ (牛棚), cowsheds. Huang’s work was declared to be counter-revolutionary, and he was denounced and severely beaten. Despite the difficult circumstances, Huang’s humor and kindness would remind his fellow artist prisoners of the joy of daily living (2017, 95-96).

After his release, Huang and his family were relocated to a cramped room on the outskirts of Beijing. The authorities, thinking they could thwart his artistic pursuits, provided him with a shed that had only one window, which faced a neighbor’s wall. However, this limitation didn’t deter Huang. Instead, he ingeniously utilized vibrant pigments that shone brightly even in the dimly lit space.

During this time, he also decided to make himself an “extra window” by creating an oil painting titled “Eternal Window” (永远的窗户). Huang later explained that the flower blossoms in the paining were also intended to “strengthen my resolve and increase the fun of living” (Hawks 2017, 4; 100-101).

Huang Yongyu’s Eternal Window [Baidu].

In 1973, during the peak of the Cultural Revolution, Huang painted his famous winking owl. The calligraphy next to the owl reads: “During the day people curse me with vile words, but at night I work for them” (“白天人们用恶毒的语言诅咒我,夜晚我为他们工作”) (Matthysen 2021, 165).

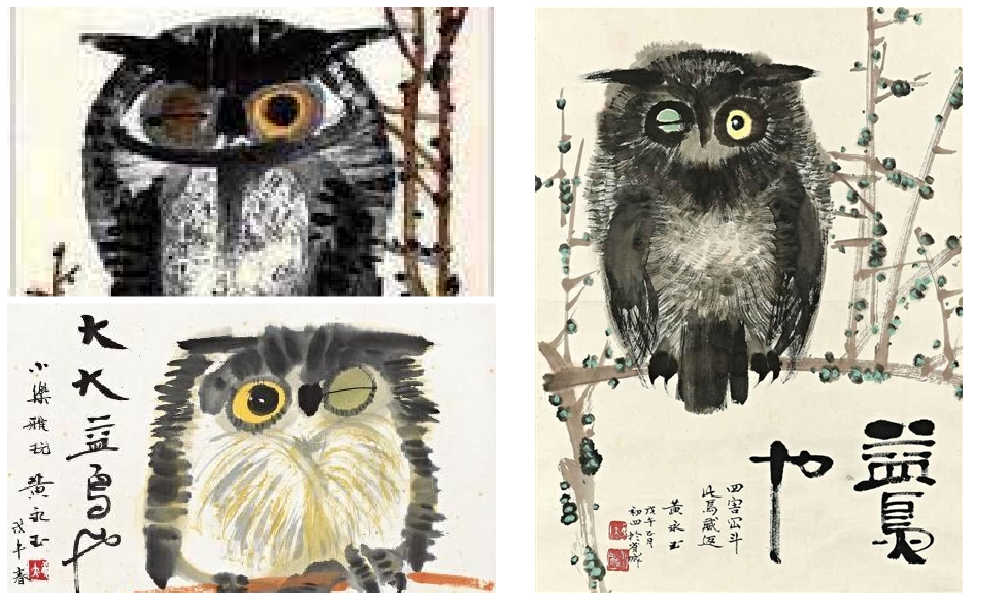

The painting was seen as a display of animosity towards the regime, and Huang got in trouble for it. Later on in his career, however, Huang would continue to paint owls. In 1977, when the Cultural Revolution had ended, Huang Yongyu painted other owls to ridicules his former critics (2021, 174).

According to art scholar Shelly Drake Hawks, Huang Yongyu employed animals in his artwork to satirize the realities of life under socialism. This approach can be loosely compared to George Orwell’s famous novel Animal Farm.

However, Huang’s artistic style, vibrant personal life, and boundary-pushing work ethic also draw parallels to Picasso. Like Picasso, Huang embraced a colorful life, adopted an innovative approach to art, and challenged artistic norms.

An Optimist Despite All Hardships

“Quickly come praise me, while I’m still alive”

Huang Yongyu will be remembered in China with love and affection for numerous reasons. Whether it is his distinctive artwork, his mischievous smile and trademark pipe, his unwavering determination to follow his own path despite the authorities’ expectations, or his enduring love for his wife of over 75 years, there are countless aspects to appreciate and admire about Huang.

One things that is certainly admirable is how he was able to maintain a youthful and joyful attitude after suffering many hardships and losing so many friends.

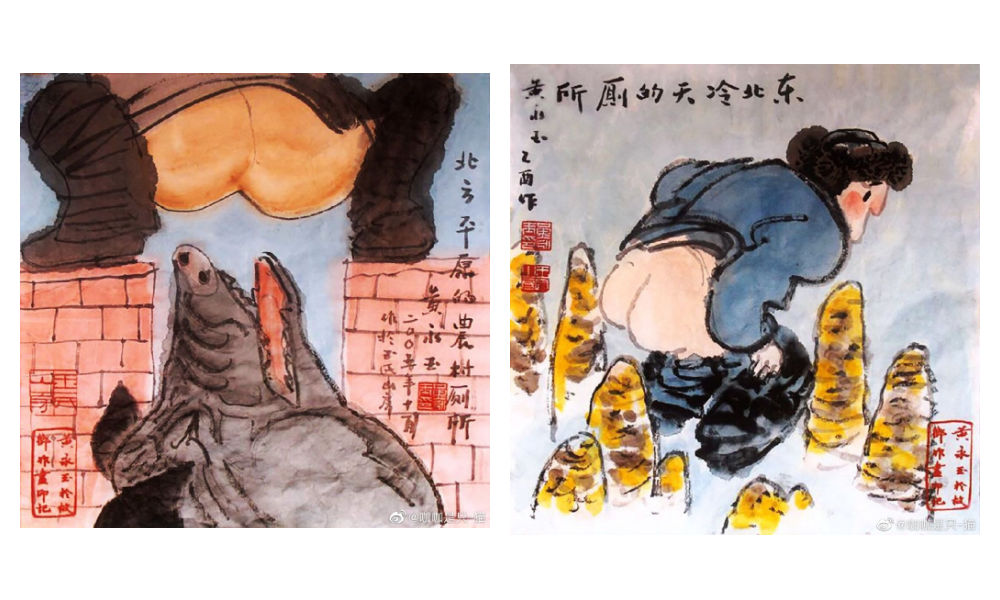

“An intriguing soul. Too wonderful to describe,” one Weibo commenter wrote about Huang, sharing pictures of Huang Yongyu’s “Scenes of Pooping” (出恭图) work.

Old age did not hold him back. At the age of 70, his paintings sold for millions. When he was in his eighties, he was featured on the cover of Esquire (时尚先生) magazine.

At the age of 82, he stirred controversy in Hong Kong with his “Adam and Eve” sculpture featuring male and female genitalia, leading to complaints from some viewers. When confronted with the backlash, Huang answered, “I just wanted to have a taste of being sued, and see how the government would react” (Ora Ora).

I'm guessing the 98-year-old Huang loved the controversy. When confronted with backlash for his sculpture featuring male and female genitalia in 2007 Hong Kong, Huang answered, "I just wanted to have a taste of being sued, and see how the government would react." pic.twitter.com/kG0MVVM4SN

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) June 15, 2023

In his nineties, he started driving a Ferrari. He owned mansions in his hometown in Hunan, in Beijing, in Hong Kong, and in Italy – all designed by himself (Chen 2019).

Huang kept working and creating until the end of his life. “It’s good to work diligently. Your work may be meaningful. Maybe it won’t be. Don’t insist on life being particularly meaningful. If it’s happy and interesting, then that’s great enough.”

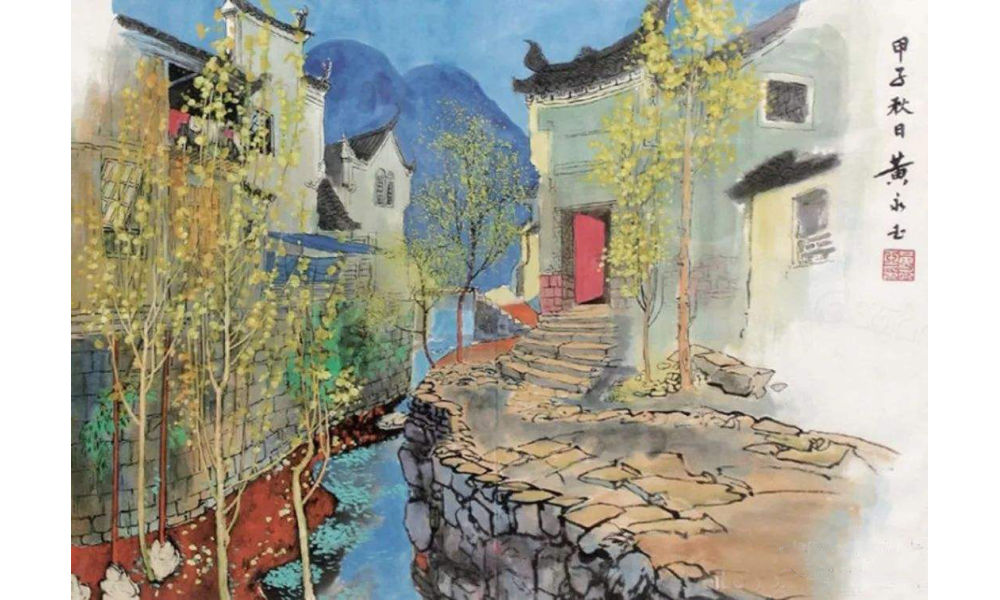

“Hometown Scenery” or rather “Hunan Scenery” (湘西风景) by Huang.

Huang did not dread the end of his life.

“My old friends have all died, I’m the only one left,” he said at the age of 95. He wrote his will early and decided he wanted a memorial service for himself before his final departure. “Quickly come praise me, while I’m still alive,” he said, envisioning himself reclining on a chair in the center of the room, “listening to how everyone applauds me” (CCTV, Sohu).

He stated: “I don’t fear death at all. I always joke that when I die, you should tickle me first and see if I’ll smile” (“对死我是一点也不畏惧,我开玩笑,我等死了之后先胳肢我一下,看我笑不笑”).

Huang with Yiwo (伊喔), the original model for the monkey stamp [Shanghai Observer].

Huang also was not sentimental about what should happen to his ashes. In a 2019 article in Guangming Daily, it was revealed that he suggested to his wife the idea of pouring his ashes into the toilet and flushing them away with the water.

However, his wife playfully retorted, saying, “No, that won’t do. Your life has been too challenging; you would clog the toilet.”

To this, Huang responded, “Then wrap my ashes into dumplings and let everyone [at the funeral] eat them, so you can tell them, ‘You’ve consumed Huang Yongyu’s ashes!'”

But she also opposed of that idea, saying that they would vomit and curse him forever.

Nevertheless, his wife expressed opposition to this idea, citing concerns that it would cause people to vomit and curse him indefinitely.

In response, Huang declared, “Then let’s forget about my ashes. If you miss me after I’m gone, just look up at the sky and the clouds.” Eventually, his wife would pass away before him, in 2020, at the age of 98, having spent 77 years together with Huang.

Huang will surely be missed. Not just by the loved ones he leaves behind, but also by millions of his fans and admirers in China and beyond.

“We will cherish your memory, Mr. Huang,” one Weibo blogger wrote. Others honor Huang by sharing some of his famous quotes, such as, “Sincerity is more important than skill, which is why birds will always sing better than humans” (“真挚比技巧重要,所以鸟总比人唱得好”).

Among thousands of other comments, another social media user bid farewell to Huang Yongyu: “Our fascinating Master has transcended. He is now a fascinating soul. We will fondly remember you.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

References

Andrews, Julia Frances. 1994. Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-1979. Berkley: University of California Press.

Baike. “Huang Yongyu 黄永玉.” Baidu Baike https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E9%BB%84%E6%B0%B8%E7%8E%89/1501951 [June 14, 2023].

CCTV. 2023. “Why Everyone Loves Huang Yongyu [为什么人人都爱黄永玉].” WeChat 央视网 June 14.

Chen Hongbiao 陈洪标. 2019. “Most Spicy Artist: Featured in a Magazine at 80, Flirting with Lin Qingxia at 91, Playing with Cars at 95, Wants Memorial Service While Still Alive [最骚画家:80岁上杂志,91岁撩林青霞,95岁玩车,活着想开追悼会].” Sohu/Guangming Daily March 16: https://www.sohu.com/a/301686701_819105 [June 15, 2023].

Hawks, Shelley Drake. 2017. The Art of Resistance Painting by Candlelight in Mao’s China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Matthysen, Mieke. 2021. Ignorance is Bliss: The Chinese Art of Not Knowing. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ora Ora. “HUANG YONGYU 黃永玉.” Ora Ora https://www.ora-ora.com/artists/103-huang-yongyu/ [June 15, 2023].

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?